The control room at BOP Studio 1 features one of only 10 Focusrite Studio Consoles ever built.

The control room at BOP Studio 1 features one of only 10 Focusrite Studio Consoles ever built.

The most lavish recording facility ever built is not in London, New York or LA, but a remote part of South Africa. We trace the extraordinary story of BOP Studios.

Ask Sound On Sound readers to name the best recording studios in existence, and I doubt that many would list Bophuthatswana Recording Studios alongside the Abbey Roads and Ocean Ways of this world. Yet when the studio complex, otherwise known as BRS or just BOP, was built in 1991 it was one of the top three residential studios in the world.

The Republic of Bophuthatswana, formerly an independent 'homeland' in the Northwest Province of South Africa close to the border with Botswana, was reintegrated with South Africa in 1994, post-Apartheid. The BOP studios are located within a secure campus on the outskirts of Mafikeng (Mahikeng or Mmabatho), which is a moderately sized town 160 miles due West of Johannesburg. The town of Mafikeng is famous for its 217-day siege in the Anglo-Boer war of 1899. Colonel Baden-Powell led the town's defence, employing local boys as 'scouts' to carry messages, and the ensuing reputation allowed him to create the Scout Movement we know today.

Viewed from space via Google Earth, the studio complex's rhinocerous-shaped layout is clear.

Viewed from space via Google Earth, the studio complex's rhinocerous-shaped layout is clear.

The money behind BOP came, rather bizarrely, from the Sefalana Employee Benefits Organisation (SEBO), which is essentially a government pension fund. Even a cursory glance around BOP reveals that no expense was spared in its construction and fit-out: definitive figures are elusive, but different sources put the cost anywhere between 22 and 91 million US dollars!

The idea behind the project was to raise South Africa's profile across the world through music, by attracting international recording artists. However, few were willing to work there during the Apartheid years, and consequently BRS suffered a fairly chequered history, operating as an independent studio for only a few years. During this period, the late Laura Branigan recorded tracks for her Over My Heart album in 1993, and of course many South African artists recorded at BOP over its working life, including Brenda Fassie, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Miriam Makeba, Stimela and the Soweto String Quartet, to name just a few.

Following a Government reorganisation in 1994, BRS was leased to the South Africa Broadcasting Corporation, which ran it as an in-house recording facility for nine years. One of its first major customers was Disney, who recorded the award-winning soundtrack for The Lion King there. Unhappily, SABC didn't renew the lease in 2003 and so the entire BRS complex was 'mothballed' — the power was turned off and the doors were locked!

In 2008 BRS was purchased by North West Consortium and the resort side of the complex was reopened, but it failed to thrive and, four years later, consortium member Mobe Investments forced an auction of the facility so that it could recover its 50-percent share. Saj Chudry, a British-born entrepreneur and another member of the original Consortium, acquired BRS at that sale for the bargain price of around US $1m, and he is currently working with the South African Ministry of Arts and Culture to try to return BRS to its former glory as a world-class recording studio complex. Some of the residential guest houses.

Some of the residential guest houses.

Bophuthatswana Studios

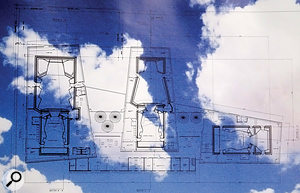

Back in the early 1990s, access to BOP was very straightforward thanks to the nearby Mmabatho International Airport. Unfortunately the MIA is not currently in use, and so the only option is a scenic three-hour road trip from Jo'Burg. The complex nestles between a golf course on one side and a hotel resort and casino on the other. A trio of huge, brick-built studio suites are joined together with a two-story building that houses offices and other ancillary rooms. Amusingly, the studio buildings were laid out to resemble the outline of a rhinoceros, Studio 3 being the head, Studio 2 the forelegs, Studio 1 the hind legs, and the ancillary offices the backbone — with the residential hospitality building forming the rhino's horn!

When BRS opened in 1991, it was a secure and self-contained luxury resort. Today it's a bit more 'tired Travelodge' than 'savoy swank', but it could be restored to its former deluxe glory very easily. There are 18 double cottages, all en-suite and with traditional thatched roofs, discretely hidden amongst mature tropical foliage and connected via illuminated boardwalks to the main resort building. This contains a large bar, restaurant and kitchens, as well as a thatched veranda overlooking the pool and Boma (an outdoor area surrounded by timber for holding barbeques or 'braais'). In such surroundings it's easy to forget about the huge studios only a stone's throw away, as they are so well hidden behind the trees!

Studio Blocks

The Swiss architects Thomas Rast used newly developed techniques to build the truly massive concrete shells for each of the three totally separate and self-contained studio suites, which were designed by Tom Hidley (see box). All control and live rooms are built as rooms within rooms to maximise isolation, with enormous windows for expansive sight lines. In addition to the control and live rooms, each suite's outer building shell also accommodates tape machine, power supply and computer rooms, a tape store, a producer's office, a lounge area with kitchen/bar and toilets, instrument and equipment storage areas, and a loading bay.

The BOP site plans amply illustrate the grand ambitions behind its design — note how large the 'shell' surrounding each studio is.

The BOP site plans amply illustrate the grand ambitions behind its design — note how large the 'shell' surrounding each studio is.

To keep background noise to an absolute minimum, the air-conditioning plant is located in a separate building behind Studio 3. During our visit it wasn't working, sadly, but when installed the ambient noise floor in the live rooms with the air-con running was just 10dBA — lower than the self-noise of most microphones! Equally remarkable was the provision of a substantial UPS capacity able to maintain the mains power supplies for the entire building for 15 minutes. A diesel generator set in a far corner of the site took over during prolonged power outages.

All three control rooms at BOP have the same layout and dimensions, with the working area being around 14 metres long and roughly eight metres wide at the broadest points. However, the walls are actually fabric-covered panels concealing acoustic treatment behind, with the concrete shell walls being some two to three metres further back on all sides. The Bass Pit Trap, unique to Hidley's infrasonic rooms (see box), stretches across the entire width of the monitor wall, and extends about two metres into the room, leaving only a narrow walkway around the rear of the console. 'Do Not Step' signs remind the unwary that the fabric covers aren't load-bearing… although there is evidence in Studio 1 that at least one person ignored the advice!

The central listening position at the mixing console is around five metres away from the monitor wall, and the huge live room windows are about three metres deep, meaning that engineer and producer are about eight metres from the live-room glass.

Flat To 10Hz

Kinoshita monitors are a standard feature of Tom Hidley's control-room designs, and the main monitors in all three BOP control rooms are soffit-mounted RM-7V models weighing 250kg each! Designed by Shozo Kinoshita and installed in over 350 studios worldwide, the RM7 is a two-way system in a 'vertical twin' configuration — an arrangement that allows the most linear phase response, which is important in a room as revealing of acoustic phase errors as Hidley's non-environment design. The RM7s were originally powered by 1kW Van den Hul solid-state amps and large rackmounting passive crossovers, both located in dedicated rooms behind each monitor soffit, but Manley 600W (KT90) valve amps have taken over the job. To achieve flat reproduction down to 10Hz, you need a powerful subwoofer!

To achieve flat reproduction down to 10Hz, you need a powerful subwoofer!

The RM7 monitor's specified bandwidth is 20Hz to 20kHz, with a maximum of 130dB SPL. That might sound a lot for a control room, but the near-anechoic nature of Hidley's design means that the sound pressure falls off at an almost perfect 6dB per doubling of distance, so the monitors need to be very powerful to deliver a generous volume at the listening position. Impressive as that is, it's still not enough to meet Hidley's infrasonic requirements, and at BOP the bottom octave is generated by a pair of Kinoshita RS-1 subwoofers mounted in the back wall either side of the producer's sofa, to produce a bowel-distressing 105dB SPL at 9Hz.

An unusual feature shared across all three control rooms is a low-level island pod in the middle of the room containing the analogue patchbay. The rear panel of this pod also carries connectors for external equipment such as outboard processors, MIDI instruments, AES3 digital tie-lines, tape machine remote controllers, and so on. Usefully, both 110V and 230V AC power outlets are provided throughout the control and live rooms, with standard UK, US and South African wall sockets. Confirming the no-expense-spared approach, the console and studio wiring is with Van den Hul silver cables: Studio 3 alone employs 11km of wiring!

Studio 3

Intended primarily as a mixing studio and for sequenced projects that don't require ensemble recording, Studio 3 has the smallest live room, with a floor area measuring roughly 5x10 metres. Its floor is about two feet below that of the control room, usefully increasing the ceiling height. Wide and heavy double-door 'airlocks' on either side of the live room provide impressive acoustic isolation while allowing easy equipment and personnel access to a large equipment store at the rear. Like all of BOP's live rooms, the walls and the floor are finished in hardwood, which looks and sounds fantastic, while the chamfered room corners contain fabric-covered acoustic traps.

The mixing console in Studio 3 is an SSL 4000G+ with Ultimation moving fader automation, providing 72 mono channel modules and eight extra stereo modules. This in-line desk is colossal at roughly 5.5 metres wide across the main section, with 24 modules either side of the centre controls. Angled side-wings accommodate 16 more modules each, as well as 19-inch bays for outboard equipment (see below).

Studio 2

Larger acoustic recording sessions are the province of Studios 1 and 2. All of BOP's live rooms feature bespoke modular headphone cue systems, with either three- or eight-channel mixers and multiple artist stations. There are custom-made instrument DI boxes around the live rooms, too.

Studio 2's large live room is capable of accommodating 65 musicians with ease. The narrow end incorporates a raised drum platform, while sliding glass doors on each side access two large isolation booths and wide side doors provide fire exits and access to a vast loading bay at the rear of the studio block. The studio acoustic is described as "vital and vigorous”, and it's certainly rich and warm-sounding, with a very even and diffuse reverberation. Tom Hidley's 'exponential room design' apparently ensures that the recorded reverb time is determined only by the distance between the microphone and source. Whatever the claimed physics of this design, it is immediately obvious that this is a very beautiful-sounding room. Studio 2 suits a wide range of musical genres, from rock and R&B, to modest classical and choral ensembles. Both this and Studio 1's live room are equipped with Fazioli 9-foot grand pianos.  Studio 2's versatile live space employs Tom Hidley's exponential room design, which is meant to ensure that the recorded reverb time is directly related to the distance between mic and source.

Studio 2's versatile live space employs Tom Hidley's exponential room design, which is meant to ensure that the recorded reverb time is directly related to the distance between mic and source.

Studio 2's control room boasts an imposing Neve VRP96 console with Flying Fader automation. This desk is an evolution of the original V-series desk, with Recall and Post-production output routing and monitoring facilities, the latter accommodating multi-channel film and TV production requirements. Like the SSL in Studio 3, the VRP provides 72 mono modules across width of the main frame, with eight stereo modules in each of the side wings, along with outboard equipment bays.  The stunning Studio 1 live room can accommodate a full orchestra with ease.

The stunning Studio 1 live room can accommodate a full orchestra with ease.

Studio 1

The flagship Studio 1 enjoys the largest live room at BRS. At 22m in length and nearly 19m wide at the control-room end, it can seat 120 musicians — a full concert orchestra — with ease, and its more complex and distinctive angled inner walls make it look and sound noticeably different from Studio 2. A similar, but somewhat larger drum riser and isolation-booth setup are provided.

As with the other studios, the acoustic design and treatment in the Studio 1 control room is quite different from that found in conventional rooms. The hardwood floor is a 16-inch thick concrete slab floating on industrial isolation springs (with a resonant frequency of 3Hz), seated on the even more massive base slab that forms the bottom of the concrete shell enveloping the control room. The live room has its own separate concrete shell structure, to maintain isolation. The front of the control-room floor stops about two metres short of the monitor wall, forming the entrance to the 'Bass Trap Pit' and its proprietary labyrinth between the slabs. The room walls are all 'soft', with acoustically transparent fabric stretched over wooden frames concealing acoustic panels behind.

Most contemporary studio treatments comprise simple foam or mineral wool absorbers parallel to the room boundaries, often supplemented with various diffusers and tuned resonant traps. Tom Hidley's 'non-environment' approach (see box) is radically different, using acoustically absorptive material surrounding wooden baffles which are suspended vertically and horizontally at precise angles and spacings along the walls and ceiling. Flanking absorber panels lie behind the angled panels, parallel to the inner 'diaphragmatic' walls, separated from the outer concrete shell by a small void space. These components form complex absorbers, diffusers and waveguides that work together to steer and trap audio wavefronts emerging from the monitor speakers, delivering a near-anechoic environment for the monitors. However, to be effective, the angled panels need to be big, and in Studio 1 they are around 7.5m long and spaced about 350mm apart. The diagrams illustrate the typical arrangement.  Realising Tom Hidley's concept of the 'non-environment' control room required massive acoustic treatment on the rear and side walls, as well as the invention of the 'Bass Trap Pit' behind the console. These two images show the rough positions and angles of the acoustic baffles in Studio 1's control room, from top and side elevations.

Realising Tom Hidley's concept of the 'non-environment' control room required massive acoustic treatment on the rear and side walls, as well as the invention of the 'Bass Trap Pit' behind the console. These two images show the rough positions and angles of the acoustic baffles in Studio 1's control room, from top and side elevations.

Providing the central wooden baffle is stiff enough, these angled panels act in a similar way to the wedges seen in true anechoic chambers, guiding the low-frequency energy to strike the flanking absorbers in a gradual manner, like waves rolling up a beach (rather than crashing into a cliff edge!). The longest dimension of the angled baffle determines the half-wavelength of the lowest frequency that can be absorbed. The low-frequency absorption efficiency of the flanking absorber panels is also increased usefully over what might be expected in free air because of the complex physics involved in the action of the angled baffles. The diaphragmatic inner wall — basically plasterboard sheets sandwiching insulation board — soaks up yet more energy from any low frequencies that make it through the panel absorbers. Although the science of the non-environment room is now fairly well understood, experience is still required to really optimise a specific room's design.

Providing the central wooden baffle is stiff enough, these angled panels act in a similar way to the wedges seen in true anechoic chambers, guiding the low-frequency energy to strike the flanking absorbers in a gradual manner, like waves rolling up a beach (rather than crashing into a cliff edge!). The longest dimension of the angled baffle determines the half-wavelength of the lowest frequency that can be absorbed. The low-frequency absorption efficiency of the flanking absorber panels is also increased usefully over what might be expected in free air because of the complex physics involved in the action of the angled baffles. The diaphragmatic inner wall — basically plasterboard sheets sandwiching insulation board — soaks up yet more energy from any low frequencies that make it through the panel absorbers. Although the science of the non-environment room is now fairly well understood, experience is still required to really optimise a specific room's design.

Holding pride of place in this flagship studio's control room is a beautiful Focusrite Studio Console (see box) with GML's moving-fader automation. Whereas the SSL and, especially, the Neve present a daunting profusion of closely spaced buttons and knobs on vast, flat, grey surfaces, the Focusrite offers a tastefully coloured array of controls in varying sizes and types, spaciously and ergonomically laid out below a castellated meter bridge. The immediate impression is just so much more attractive and inviting and, given the choice, I'd much rather spend a working day in front of the Studio Console than any other… and that's before listening to it, which very quickly clinches the deal! This is an uncannily quiet console with that wonderful ISA sound running through its veins. Once again, VdH silver cables are used for the entire console and studio wiring.

Overboard On Outboard

Studio 3 was intended mainly for mixing and overdubbing. Tom Hidley's 'non-environment' control room houses a huge SSL desk.A wide range of outboard equipment is installed in the side wings of all three consoles, with more on rack trolleys that can be moved between areas as needed. The Aphex Aural Exciters and BBE Sonic Maximisers conjure up a time-warp image of the mid-1990s, but there are also numerous desirable and timeless classics. In addition to various Focusrite, Neve and SSL rack modules, there are also familiar devices like Dbx 165A, Manley Variable Mu, SSL FXG384 and Urei 1176LN and LA4 compressors. Outboard EQ is provided by Manley's Pultec and Mid-frequency units, TC Electronic's TC1128 and BSS DPR901s, while reverbs and delays include AMS S-DMX 15-80 and RMX16 units, Klark Teknik DN780s, Eventide H3000SE Ultra-Harmonizers, Lexicon 300s, PCM70s and PCM42s along with various Yamaha SPX processors.

Studio 3 was intended mainly for mixing and overdubbing. Tom Hidley's 'non-environment' control room houses a huge SSL desk.A wide range of outboard equipment is installed in the side wings of all three consoles, with more on rack trolleys that can be moved between areas as needed. The Aphex Aural Exciters and BBE Sonic Maximisers conjure up a time-warp image of the mid-1990s, but there are also numerous desirable and timeless classics. In addition to various Focusrite, Neve and SSL rack modules, there are also familiar devices like Dbx 165A, Manley Variable Mu, SSL FXG384 and Urei 1176LN and LA4 compressors. Outboard EQ is provided by Manley's Pultec and Mid-frequency units, TC Electronic's TC1128 and BSS DPR901s, while reverbs and delays include AMS S-DMX 15-80 and RMX16 units, Klark Teknik DN780s, Eventide H3000SE Ultra-Harmonizers, Lexicon 300s, PCM70s and PCM42s along with various Yamaha SPX processors.

Though it pre-dates the widespread use of computer recording, BOP was built at a time when digital multitracking was the state of the art. So, along with the Studer A820 analogue 24-track and two-track recorders littered about the place, there are also various 'legacy' Sony, Mitsubishi and Studer digital recorders. Even more extraordinarily, stored in Studio 3's machine room is a complete New England Digital 'direct to disk' Synclavier system.

The machine rooms associated with each studio suite are equipped with dedicated connection panels for all of these recorders and their associated remote controls, along with analogue console sends and returns, timecode, digital tie-lines and so forth. It's very obvious that a lot of thought and effort — and expense! — went into the design of the studio's technical infrastructure.

Lost & Found

Visiting BOP Studios was something of a bittersweet experience. I remember being enthralled when reading about the place in trade magazines over 20 years ago, but I never imagined I'd have the opportunity to visit. The experience of walking into those huge live rooms and fabulous control rooms was everything I'd imagined it to be, and the studios are every bit as awesome to behold now as when they were first built. The huge analogue consoles are the stuff of every wannabe engineer's dreams, and the fabric of the building is generally in remarkably good condition considering it is 22 years old and was mothballed for a decade.

However, there's no denying that BOP is in need of some careful maintenance and renovation. At some point, rain got in and damaged ceilings and parquet flooring around Studio 1's office, tape store, toilets and lobby areas. Many light bulbs have failed throughout the building, leaving most areas very dark and gloomy, and the UPS and air-conditioning are both currently non-functional. Big analogue consoles can be temperamental at the best of times, and after being turned off for a decade, I'm sure they all need re-capping and a thorough overhaul to regain their original quality and reliability. Apparently the magic smoke escaped from the Neve console after extended overnight use without functioning air-con, and no one has dared turn it on since! The SSL wasn't powered while I was there, and I'm not convinced all of the Focusrite was working fully either.  Saj Chudry intends to bring BOP back to its former glory.

Saj Chudry intends to bring BOP back to its former glory.

Having said that, a competent, resourceful and enthusiastic chief engineer would be able to restore the complex to its premiere condition in a relatively short time. It's a classic chicken-and-egg scenario: funding is needed to get everything working again, but it needs to be working to generate the funding. The man who has to square that circle is the new owner, Saj Chudry.

While it's quite obvious that simple asset-stripping would easily recoup Chudry's investment, the real value of the BOP complex is actually in the buildings themselves and their acoustic design. No one could conceivably build anything of the like today — it just wouldn't be economically viable — and control rooms of this calibre today can be counted on the fingers of two hands, with some to spare! Thankfully, the new owner seems genuinely focused on getting BOP back up and running as a studio complex, one way or another, despite the obvious challenges that lie ahead.

The music industry today is very different from 20 years ago, and as a conventional recording studio, BOP would struggle to be profitable even if it were in London, New York or Los Angeles. Its actual location in Mafikeng perhaps adds to these difficulties, but also points to other opportunities. It's a sad but true fact that there are more big analogue consoles today in educational facilities around the world than in top recording studios. With accommodation and classroom facilities already on site, and African sunshine and local wildlife parks on hand, BOP could generate significant income as a residential college. I'm certain a lot of people would pay handsomely for a fortnight of masterclasses and workshops in such world-class studios, under the careful tutelage of leading engineers and producers. Whatever happens, I shall follow BOP's progress over the months and years to come, and I'll always treasure the opportunity I had to experience something of the place.

Origin Of The Focusrite Studio Console

BOP's Focusrite Studio Console number 5 (of 10).Rupert Neve established Focusrite in 1985, building upgraded input modules for George Martin's original Neve console at Air studios in Montserrat: the ISA110 preamp/EQ module and, later, the ISA130 dynamics module. Focusrite was then persuaded to design a full console based on these modules, resulting in the Forte Console, which appeared in 1988. This was, without doubt, the most highly specified mixing console ever produced, but only two consoles were manufactured (one for Electric Lady in New York and the other for Master Rock in London) and the expense forced Focusrite into administration.

BOP's Focusrite Studio Console number 5 (of 10).Rupert Neve established Focusrite in 1985, building upgraded input modules for George Martin's original Neve console at Air studios in Montserrat: the ISA110 preamp/EQ module and, later, the ISA130 dynamics module. Focusrite was then persuaded to design a full console based on these modules, resulting in the Forte Console, which appeared in 1988. This was, without doubt, the most highly specified mixing console ever produced, but only two consoles were manufactured (one for Electric Lady in New York and the other for Master Rock in London) and the expense forced Focusrite into administration.

Serendipitously, Phil Dudderidge had just sold his share in Soundcraft Electronics and bought the Focusrite assets in 1989. Although the Forte was unviable, there was demand for a more conservative and evolved tracking console based on the ISA modules, so Focusrite Engineering's first new project was the Studio Console. Building it gave Focusrite the honour of being the last major player to enter the big analogue studio console market… and the first to get out of it! Though the ISA preamp, EQ and dynamics designs live on in current Focusrite products, only 10 Studio Consoles were ever built, and just seven survive today — BOP's desk is number five.

Unlike the SSL 4000G and Neve VRP 'in-line' consoles of the time, which had two signal paths through each module (input and monitor paths), the Focusrite Studio Console had only a single path through each module, with each eight-channel bay being switched centrally between input and monitor sources, making it more like a 'split' console. An unusual aspect of the Studio Console was the use of devolved mix buses: each eight-channel bay contained its own local summing buses, the outputs from which went to the master mix buses in the centre section. This approach provided significant technical and practical advantages, including very low mix noise and easier installation.

Tom Hidley

Tom Hidley is a legend in the world of high-end studio acoustic design, having built well over 500 control rooms around the world. He started designing recording studios in 1965 and formed his Westlake Audio company in California four years later. Working with two partners, Westlake Audio sold complete studio packages, containing everything from the microphones to the console, the tape recorders, the monitoring system, and the design and construction of the studio space to house it all! Westlake's marketing tagline was "From design to downbeat” and the company's rooms even came with a written guarantee. By the mid-'70s a lot of producers and engineers would only work in 'Westlake' rooms, such was their reputation!

Hidley is the first to admit that he was learning as he went — there were no books and very little research on studio acoustic design back then — so each new room evolved through trial and error from preceding ones. Nevertheless, the influence of his pioneering acoustic designs can still be seen across the recording studio world 40 years on. For example, Hidley introduced the idea of soffit-mounted monitors, the use of sliding glass doors between live and isolation rooms, and he even coined the term 'bass trap' — and that was just in 1969!

After designing some studios in Europe, including Richard Branson's Manor Studios, Hidley wanted to set up a European office, but his partners weren't interested. Consequently, Hidley sold up, moved to Switzerland, and started a new company called Eastlake Audio in 1975 (can you see what he did there?). His new business concentrated purely on studio acoustic design and construction and did very well, but by the end of the 1970s Hidley felt that he had taken his studio acoustic designs as far as he could — there was a performance limit that he couldn't overcome — and in 1980 he sold the business to take early retirement in Hawaii.

Hidley's interest in acoustic design didn't diminish, though, and while relaxing on the beach one day he suddenly realised that the fundamental problem of his acoustic designs up to that point was due to reflections compromising the sound produced by the monitors. Suitably inspired, and after trying out his new ideas on a project in Japan, Hidley returned to Switzerland in 1986, started a brand new business under his own name, and immediately started building studios to his new design concept, which became known as the 'Non-Environment' control room (see box).

The Non-Environment Control Room

In the 1970s, most control rooms used reflective surfaces around the front of the room with very absorbent areas at the back. However, variations in room size, shape and construction materials meant that no two control rooms ever sounded the same, stereo imaging was poor, and mixes just didn't 'travel' well. To address these problems, acousticians in the 1980s turned the idea on its head with the introduction of the LEDE — 'live end, dead end' — concept. Now the back of the room was made reflective, typically with large diffusers, while the area around the monitors and console was made very absorbent, to ensure only direct sound from the monitors came from that direction. LEDE rooms sounded more neutral and more consistent, but there were still issues with getting mixes to travel — and that led to the widespread use of nearfield monitors, which gave the engineer more direct sound and less reflected sound. However, nearfields could never match main monitors for bandwidth, dynamic range, transient accuracy, and so on, so in effect, monitoring accuracy was being sacrificed to circumvent the room's acoustic failings. This in turn influenced the dynamic style of mixes.

Tom Hidley's Non-Environment (NE) approach removed control-room reflections altogether! Monitors work best, and are tested, in anechoic conditions, but people don't like working in an anechoic space. Hidley's innovation was to design a room that was anechoic as far as the monitors were concerned, but provided a natural-sounding environment for the users. To achieve this, Hidley had to revolutionise the way low frequencies were managed, using waveguides and diaphragmatic absorbers, 'symmetrical unloading', and various other innovative techniques.

Hidley had already standardised the use of soffit-mounted monitors to avoid problems such as cabinet-edge diffraction, but his Westlake and Eastlake control rooms employed monitor walls constructed, basically, from timber. Not surprisingly, these tended to vibrate at low frequencies, and so some of the monitor speakers' energy was lost into the wall structure. Hidley's solution from 1986 was to use massive monitor walls built from poured concrete, incorporating concrete soffits for the monitor cabinets. This ensured that all of the acoustic energy from the speaker was sent into the room, while simultaneously extending the speakers' baffle area to improve significantly the low-frequency efficiency and linearity of the monitoring system.

The concrete monitor wall, usually clad in wood panelling, was reflective to sound sources in the control room, as was the hardwood flooring Hidley always employed. So, from the perspective of anyone working in the room, the acoustic is similar to being out of doors, since the strongest reflections come mainly from the ground, with some from the monitor wall and equipment. The presence (and predominantly vertical orientation) of these reflections prevents the room from feeling unpleasantly 'dead', and actually sounds reassuringly natural. However, the monitors can't 'see' the monitor wall at all since they are part of it, and as the control room's rear and side walls and ceiling are completely absorbent, the monitors are in effect working into a room which approximates an anechoic chamber. Sound from the monitors spreads through the room in a natural way but generates no reflections at all — hence the 'Non-Environment' moniker.  This photo shows the 'Bass Trap Pit' behind Studio 1's Focusrite console, and the massive soffit-mounted Kinoshita monitors. These are powered by amps and crossovers mounted in dedicated rooms behind the thick concrete walls.

This photo shows the 'Bass Trap Pit' behind Studio 1's Focusrite console, and the massive soffit-mounted Kinoshita monitors. These are powered by amps and crossovers mounted in dedicated rooms behind the thick concrete walls.

There is, though, one small caveat to this cunning plan. The acoustic interfaces between the monitor wall and ceiling, and between the monitor wall and the side walls, are 'unloaded', meaning the low-frequency wavefronts produced by the monitors are fully absorbed as if the monitors are firing out into open space. However, the wall-floor junction involves two solid boundary surfaces, so the loading is unsymmetrical in that axis, resulting in a very uneven and unacceptable low-frequency response. Hidley's ingenious solution was the 'Bass Trap Pit' which he used for the first time at BOP. In essence, the control-room floor is floated above the room's structural shell base slab on industrial isolation springs, and the void between the two is used as a bass-trapping labyrinth, which sound enters through a very large slot across the full width of the bottom of the monitor wall. In this way all four monitor wall boundaries become 'symmetrically unloaded' and the monitors are working into a very good approximation of an anechoic chamber. With a negligible acoustic contribution from the room, its shape, size and contents no longer affect monitoring quality and accuracy, and mixes 'travel' extremely well. Control-room reverberation is, in effect, just more unwanted noise that masks detail; and with transient and phase accuracy greatly improved, mic placement, mixing and processing decisions become far easier and clearer.

The down side is that the structural shell has to be very much larger than the finished room size to accommodate all the acoustic treatment needed to maintain a near-anechoic performance at very low frequencies, although Hidley's innovations minimised the additional space required quite significantly over simpler designs. In particular, the non-environment concept evolved significantly with the breakthrough innovation of diaphragmatic absorbers near the room boundaries which, along with resonant cavities and waveguide techniques, allowed excellent low-frequency absorption to be achieved with treatment depths of just three metres.

With excellent low-frequency control now practical, it became possible to extend the monitor bandwidth downwards while maintaining proper damping, and this led to Hidley's 'Infrasonic' room concept. Hidley's first trial of the idea was in 1983 at Sedic Studios in Tokyo, which were capable of flat reproduction down to 30Hz. This was followed by 20Hz rooms at Masterfonics in Nashville in 1986 and Nomis in London in 1988. However, the realisation of the full infrasound concept came with the construction of BOP's three 10Hz control rooms, and subsequently the 'infrasound-ready' Tracking Room at Masterfonics in 1995.

Despite the enormous costs and design complexity, the benefits of the infrasonic control room are quite audible and tangible. The low-frequency phase linearity and transient response bestows a natural realism that I've never heard from any other monitoring system anywhere. I first auditioned Hidley's infrasonics in action at Masterfonics in Nashville, shortly after the Tracking Room was completed, and I'll remember that experience for the rest of my life!

Video Tour

Watch the Sound On Sound video tour of BOP Studios with Hugh Robjohns.

Hugh Robjohns interviews the new studio owner Saj Chudry and Focusrite's Phil Dudderidge.