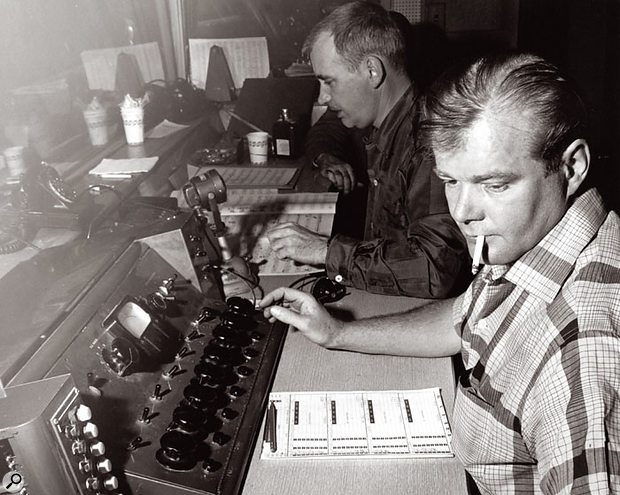

Bench-testing new equipment in the Universal Audio laboratory.Photo: Universal Audio

Bench-testing new equipment in the Universal Audio laboratory.Photo: Universal Audio

Some of the legendary names in engineering and production didn't just make great records — they also invented equipment and techniques we take for granted today.

The confluence between musicians and inventors goes back hundreds, if not thousands of years. Even the words 'invent' and 'improvise' are often interchangeable. However, the ability to think outside the box, which we expect musicians to do, and yet do so in a methodical, calculated manner, is a requirement very few are expected to fulfil. Thomas Edison may have invented the recording process, but I can't recall any of his songs ('Mary Had A Little Lamb' does not count). Les Paul, on the other hand, figured out how to record an entire band with one person in the room and did it while composing 'Vaya Con Dios'. It's worth looking at how some synthesized their creativity and inventiveness, in the process impacting our own lives and careers. And just keep in mind as you read, every time you have to navigate an ingenious patch around a problem in the studio, you're emulating what these folks did.

Meek By Name, Not By Nature

Joe Meek's father returned from WWI after having a horse shot out from under him and seeing his friends blown to bits on either side of him. Joe would find himself in the line of fire himself later in his life, which ultimately proved just as violent and lethal. He was also tone-deaf and had no sense of rhythm, none of which stopped him from composing and recording timeless songs, including the Cold War classic 'Telstar', and creating a compendium of studio techniques, including flanging and close-miking, and hardware such as one of the first spring reverb units, that today are so commonplace that they seemed to have always been there.

"Joe Meek was a scientist to the extent that he was the 'Wacky Professor', though not nearly as benevolent," observes Barry Cleveland, who wrote the definitive technical biography of Meek, Creative Music Production: Joe Meek's Bold Techniques (available at www.artistpro.com and www.barrycleveland.com). "His temper was legendary — he regularly and literally threw musicians and their equipment down the three flights of stairs from his apartment," at 304 Holloway Road.

The most famous of Meek's 'black boxes' was the spring reverb unit he fashioned from a broken HMV-made fan heater in 1958. While working at the IBC-owned Lansdowne House studio in Holland Park, London, he also developed a compressor/limiter based on Langevin designs and an EQ based on a Pultec, described by its current owner, Nigel Woodward, as "probably the warmest, smoothest, most transparent equaliser ever made."

Joe Meek in the cutting room at IBC Studios.Photo: AOK Ware, with thanks to Denis Blackham

Joe Meek in the cutting room at IBC Studios.Photo: AOK Ware, with thanks to Denis Blackham

"Joe made a lot of things based on existing designs, but he took them to another level," says Cleveland. As a scientist, Meek was assertively autodidactic — his only formal technical training came during his National Service stint as a radar technician. But as a teenager he built a television set from scratch, despite the fact that TV signals hadn't reached his part of the country yet. "As a technology developer, Joe was largely intuitive," says Cleveland. "He considered himself as very technical, but he had very little formal technical education. What he could do very well, though, was conceptualise something — a sound, a way of recording — and then find a way to achieve it."

Meek's fellow engineers at Lansdowne and other studios were reportedly both disdainful and jealous of his capacity to try new techniques, and in doing so, he upset the highly conservative and hierarchial order that was the atmosphere in the British music recording industry at the time. "The orthodoxy then was to use few microphones, placed away from the sound source, and use a lot of natural room ambience," says Cleveland. "Exactly this microphone was placed exactly here for each instrument. It was all done by rote. Meek ignored the rules and put whatever microphones he wanted to wherever he wanted to, usually a lot of them placed close to the sources, and then used artificial ambience like reverbs to create a sense of space. This approach to recording is what gave engineers the kind of control over sound that today we take for granted in the studio. He taught us to create sounds rather than just attempt to control dynamics."

According to Cleveland, Meek was the first engineer in the UK to use compressors to create pumping and breathing effects rather than to merely to control dynamic range. He also pushed limiters to the max to get the hottest possible levels on tape and took advantage of analogue tape's natural compression characteristics. It is also likely that Meek was one of the first engineers to direct inject the electric bass by plugging it straight in to the mixer.

If it's true that there is a fine line between genius and madness, then Meek straddled that boundary. His pathologies rivalled his accomplishments, and included depression, pharmaceutical abuse and paranoid schizophrenia, causing him to cover many of his inventions with tape lest they be seen and copied. "He thought everyone was out to steal his secrets," Cleveland says. "Still, the innovative techniques he devised were done in studios for all to see. He was not a note-taker, so that's how his innovations became part of the way records came to be made — because people did see what he did and copied it." Meek would disregard regulations and never 'zero' any piece of gear, leaving parameters with his settings and often leaving entire pieces of equipment modified with their chassis lying open. Joe Meek was troubled, in the way many artists and innovators are. The way he tried to deal with his demons ultimately failed — he committed suicide in 1967 — but left the industry with a legacy that changed the course of sound recording.

Tom Dowd: Change The Machine, Not The Man

In many ways Meek's opposite, Tom Dowd was equally instrumental in changing the way records were made as chief engineer and later producer for Atlantic Records, where he was involved in records for the Clovers, Ruth Brown, Joe Turner, Clyde McPhatter, LaVern Baker, the Drifters and Ray Charles, with whom he illustrated his unique ability to turn out records that sold equally well on both sides of the racial divide — which in and of itself was a remarkable accomplishment for the time.

Tom Dowd mixing Derek & The Dominos' 'Layla'.

Tom Dowd mixing Derek & The Dominos' 'Layla'.

Dowd's scientific and musical background was as formal as Meek's was ad hoc. Dowd attended the prestigious science and mathematics-oriented Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan, graduating at the age of 16 in 1942. He began taking classes at City University and Columbia University, also playing trombone and drums in Columbia's band, adding to the violin and piano that his mother, a classically trained opera singer, and father, who designed sets at the Roxy Theater on Broadway, had encouraged as a child. He registered with his draft board in 1943 upon turning 18 in October of that year, and his scientific background did not go unnoticed: he was assigned to the Special Engineer Detachment, Manhattan District, one of a web of university-based scientific cells working on the myriad components of what would come to be called the Manhattan Project — the effort to build the atomic bomb that ended the war. During his stint on the project, Dowd operated a cyclotron, performed density tests of various elements, and recorded statistics as part of the neutron beam spectography division.

"When the war was over, Tom came out of the service and wanted to finish his degree at Columbia," Dana Dowd, Tom's daughter and now the manager of his estate, told me. "He found that he needed just a few physics and math classes to graduate, so he asked the school to give him the credits because of the work he had done during the war. He didn't want to go to a classroom where a professor would tell him there were this many elements in the universe after he had spent two years helping develop technologies that discovered new elements. It would have driven him crazy." Unfortunately, the nature of Dowd's wartime work was top secret, so the school declined to award credit and Dowd went off to work for a radio station, engineering music sessions on the side. Physics' loss was pro audio's gain.

Teaming with Atlantic Records' vice-president and producer Jerry Wexler, Dowd worked at the major independent facilities of the day in New York and later designed a series of studios there for Atlantic. As Dowd became more entrenched in music engineering, Wexler found himself relaxing a bit. "With Tom around, I never had to touch a fader," he told me from his home in Florida, and he credits Dowd as the engineering genius behind the many hits they made together.

In fact, those faders Wexler refers to were Dowd's invention, as well. Dana Dowd asserts that her father was the first to use faders instead of the huge Bakelite knobs then common on music consoles. "He was a piano player, and he wanted to be able to play the console the same way he could the piano: with several keys in each hand," she says. "With the knobs, you couldn't have more than one in each had at a time. So he found a company that was making wire slider [potentiometers] and installed them into the console at the first Atlantic Studios. Too bad he didn't patent the idea."

Where Joe Meek was secretive to the point of being furtive, Dowd — who probably had enough of secrecy during the war — was good at project management and identifying people to whom to delegate tasks. "He hooked up with Mac Emerman [founder of Criteria Studios in Miami] and Jeep Harned [founder of console and tape-deck maker MCI] and would say 'This is what we need to do, this is what we need to do it with. You guys build it,'" recalls Trevor Fletcher, longtime general manager at Criteria Studios. "He had a very technical mind but he was also good with people and had the common sense to know when someone else could do something better than he could. He created the amalgam of needs that became the specs for Criteria and had Mac put it together. But he didn't wait for people to act. He told me the story about when he went to Muscle Shoals the first time to do records there with Jerry Wexler and Rick Hall. The only tape machine in town was broken. Tom called around, found the part and fixed it."

Tom Dowd remained deeply engaged with both music and technology until his death in 2002.

Bill Putnam: Mixing Technology & Business

As well as designing much of the equipment that went into his studios, Bill Putnam also planned and built the studios themselves. Photo: Universal AudioKey components of the heyday of analogue recording can be traced back to one man. Bill Putnam not only devised classic equipment like the 1176N and Urei Time Align monitors, but he also designed and built equally classic recording facilities to use them in, such as Universal Audio in Chicago and United Recording in Los Angeles. Putnam also made records: the Harmonicats' 'Peg-O-My-Heart', which Putnam recorded in 1947, was not only a million-seller but is also widely acknowledged as the first pop record to use artificial reverberation, which came in the form of a tiled toilet at Universal to which the vocal signal was sent.

As well as designing much of the equipment that went into his studios, Bill Putnam also planned and built the studios themselves. Photo: Universal AudioKey components of the heyday of analogue recording can be traced back to one man. Bill Putnam not only devised classic equipment like the 1176N and Urei Time Align monitors, but he also designed and built equally classic recording facilities to use them in, such as Universal Audio in Chicago and United Recording in Los Angeles. Putnam also made records: the Harmonicats' 'Peg-O-My-Heart', which Putnam recorded in 1947, was not only a million-seller but is also widely acknowledged as the first pop record to use artificial reverberation, which came in the form of a tiled toilet at Universal to which the vocal signal was sent.

It should be noted that Putnam was as comfortable with the business of audio as he was with the technology of it. The Harmonicats record underscores that: he financed the recording in return for a piece of the profits. He would pull a similarly profitable coup years later when, in the late 1950s, record labels were still unconvinced of stereo's sales potential. Putnam, however, felt otherwise, and began mixing everything he did in stereo as well as mono. When stereo finally did take off in the early 1960s, labels scrambled for content to fill their catalogues and Putnam was waiting for them, collecting a handsome premium for his anticipation of the situation.

Putnam's list of accomplishments is huge. He developed the first multi-band equalisers, was a pioneer in studio acoustics and design, designed the 1108 FET preamp, and was a leader in half-speed mastering techniques — usually on mastering equipment he built himself.

Bill Putnam at one of the mixing consoles he designed. Photo: Universal Audio

Bill Putnam at one of the mixing consoles he designed. Photo: Universal Audio

Putnam was born in 1920, at the beginning of the radio age, and like Meek and others was fascinated by sound to the point that he built his first radio at the age of 15. Putnam's father seems to have been a template for much of his son's future development: he was a businessman who also produced radio programmes. In high school, he assembled, rented and repaired PA systems, while also singing on weekends with dance bands, for five dollars a night — which included the PA rental.

Bill Putnam had much of Meek's intensity, but was able to channel and harness it, thanks largely to an innate ability to see the fiscal as well as the sonic potential of new ideas. Like the other inventors talked about here, Putnam's inventiveness stemmed mainly from the need to create solutions to difficulties he encountered while working as a producer and engineer. His son, Bill Putnam Jr, puts it succinctly. "He was a guy who built equipment to solve problems in the studio." That approach, which truly did put the music before the moolah, kept him in demand by artists including Nat 'King' Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington (Putnam was reputed to be the Duke's favourite engineer) and Count Basie. That, in turn, pushed Putnam's own limits and compelled him to create new solutions to audio issues as they arose, many of which resulted in equipment still used regularly today. Bruce Swedien, who went to work for Putnam at Universal in Chicago as a teenager, relates on the Universal Audio web site: "Bill Putnam was the father of recording as we know it today. The processes and designs which we take for granted — the design of modern recording desks, the way components are laid out and the way they function, console design, cue sends, echo returns, multitrack switching — they all originated in Bill's imagination."

Another of Bill Putnam's mixing desks.Photo: Universal Audio

Another of Bill Putnam's mixing desks.Photo: Universal Audio

Tom Scholz: The Rockman

Painfully thin and angular in the consumptive manner of Romantic poets, Tom Scholz is what all musical geeks aspire to be. He graduated at the head of his classes in Mechanical Engineering degrees (bachelors and masters) at MIT in Boston, the city he would name his band after. For someone legendary in the music industry for procrastinative perfectionism — Epic Records sued Scholz and Boston for $20 million to get the band to release their third record, one of only three they would release over 11 years on the label — Scholz generated a prodigious output when it comes to invention.

Scholz Research & Development (SRD) is built upon Scholz's inherent scientific nature and the experience he gained working as a design engineer at Polaroid in the early 1970s. In 1980, in between the second and third Boston albums, SRD released the Power Soak, which, using a series of resistors between the output of a 100 Watt tube amp and a speaker cabinet, allowed for big sounds at low volumes and was an instant hit with guitarists (and SPL-stunned engineers). In 1982 came the Rockman, a belt-worn solid-state headphone amp which reproduced the guitar sounds he astounded the world with on the debut Boston album. The company went on to release numerous related products, and Scholz personally was awarded over two dozen design patents before he sold SRD to Dunlop in 1995.

Scholz's musical background was more classical than pop — he played piano as a child and didn't pick up the guitar, which would become his trademark, till he was 21. The same ability to synthesize science and music that made Boston's records so unique-sounding also helped Scholz create products that helped feed the niche being carved by Tascam's Portastudio: he was taking what previously had required large amounts of space, technical adroitness and volume (not to mention money) and putting it into a simple, affordable box. Like Bill Putnam, Scholz recognised the need to acknowledge a market, not just solve a studio challenge.

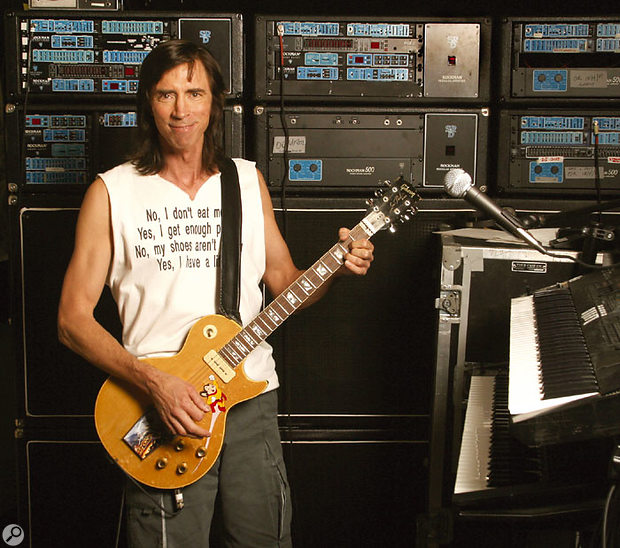

Tom Scholz, with his wall of Rockman gear.Photo: Ron Pownall, courtesy Boston

Tom Scholz, with his wall of Rockman gear.Photo: Ron Pownall, courtesy Boston

"I was a fixer, a builder — an inventor — ever since I can remember," Scholz once told writer Larry Lange in an interview. John Boylan, who produced Boston's debut record, which has sold over 16 million units, recalls that Scholz's engineering foundation was critical to the music, and provides insight into how Scholz created the Rockman. "When the first album was a huge success, and he had some money, [Tom] bought a special oscilloscope which would freeze-frame the waveform of an audio signal," Boylan explains. "He would play the guitar sound into the 'scope, freeze the waveform, then take a picture of it with a special Polaroid camera that he had acquired when he worked there. He used this method to be sure that he was always getting the same guitar sound.

"To me, Tom Scholz is interesting because he got his start with engineering that had nothing to do with audio. He helped [Polaroid chief] Ed Land perfect the ill-fated instant movie camera. The two technical achievements that he had worked out on his own that impressed me were his use of analogue, bucket-brigade delay on guitars, and his use of a variable resistor between the Marshall 100 Watt head and the cabinet, which he later marketed as the Power Soak." Still Boylan contends, "I'd venture a guess that the two domains of inventor and engineer are in separate compartments of his thinking process."

Business was definitely compartmentalised. "I hated it," Scholz told Larry Lange of his brief career as an entrepreneur, despite selling tens of thousands of products. He continues to use analogue recording techniques and technologies — he still has a stash of Scotch 226 tape — and live Boston performances continue to haul with them a ton of studio-level gear connected in complex ways. One can wear more than one hat, but not all of them always look good on you.

George Massenberg

Like other audio inventors, George Massenberg showed a proclivity for music and technology at an early age — at 15 he was working part-time both in a recording studio and in an electronics laboratory. In his '20s, he was chief engineer of Europa Sonar Studios in Paris, France in 1973 and 1974, and also did freelance engineering and equipment design in Europe during those years. He founded his technology company, GML, in 1982 to make devices he wanted for his own projects, most notably the first parametric equaliser, as well as refinements to console automation systems, which ultimately earned him a Grammy award for Technical Achievement. He has been equally fecund on the other side of the console, earning two Grammy awards for his work with artists including Billy Joel, Kenny Loggins, Journey, Lyle Lovett, Toto, the Dixie Chicks, Mary Chapin Carpenter and Linda Ronstadt. He has designed, built and managed several recording studios, including the Complex in Los Angeles.

Like Dowd, Massenberg had issues with the rigidity of academic science. While taking Electrical Engineering at Johns Hopkins University — a school he describes as "medieval, apathetic and oppressive as schooling in the '60s could get" — he got into a row with a teacher who looked at a schematic for a gyrator that he had built and declared it 'of theoretical interest only' and 'impractical' to implement. "Seeing this as a sign," he says, "I dropped out of college."

George Massenburg.John Boylan, who has worked with Massenberg for years and owns one of Massenberg's early ITI parametric units, reminds us that "George was also a significant innovator in the field of limiting — his compressor/limiter has certain variable parameters that no other unit has. With George, the two domains [of science and art] interact in music. Unlike many tech-heads who are either unaware or not interested in what it is they are recording, George has a true feeling for the music. He's really a renaissance man."

George Massenburg.John Boylan, who has worked with Massenberg for years and owns one of Massenberg's early ITI parametric units, reminds us that "George was also a significant innovator in the field of limiting — his compressor/limiter has certain variable parameters that no other unit has. With George, the two domains [of science and art] interact in music. Unlike many tech-heads who are either unaware or not interested in what it is they are recording, George has a true feeling for the music. He's really a renaissance man."

"I don't believe anything is totally original or creative," Massenberg explains, in response to a question about how his own creativity applies to music and technology. "Nothing is created in a vacuum. Things are created and invented in response to awareness of a need. You're sitting in the studio and something will piss you off and after the nth time it bothers you, an idea will begin to emerge."

It's what one does with the idea that sets the entrepreneurial apart from the creative, Massenberg believes. If the process of invention is non-linear and draws from an array of sources, as he says it does, then turning an inspiration into a practical and (hopefully) bankable reality requires other skills. He makes a trenchant, almost startling statement: "Those who are motivated by entrepreneurship and profit create products that are distinctly different from those created by people motivated by need." The comment prompts Massenberg to observe further that there seems to be a parallel between the state of the music industry and that of the pro audio equipment sector. "The market has taken over the creation and development of boxes, just as conglomerates have taken over record labels and radio," he says. "The loss of creativity in both domains is palpable."

That said, though, Massenberg also believes that new technologies and platforms can still be created by individuals searching for tools that the market hasn't yet discovered in focus groups. "The way for that to happen, though, is for people to rearrange their priorities," he says. "Don't calibrate your thinking to what common wisdom says is what you should be working on or thinking about. Guard against arrogance and insularity. And leave yourself open to serendipity. That's where invention flows from."