"When we originally mixed Avalon in stereo, I was thinking that it should be in surround," says Bob Clearmountain. Twenty-one years on, he and producer Rhett Davies describe how they first made Roxy Music's classic album and how they finally got the chance to mix it in 5.1.

Bob Clearmountain.Photo: Piers Allardyce"This record probably means more to me than anything I've ever done," says Bob Clearmountain of Roxy Music's last, and most successful, studio album. "I've had more comments and compliments on this album by far than anything else I've ever done."

Bob Clearmountain.Photo: Piers Allardyce"This record probably means more to me than anything I've ever done," says Bob Clearmountain of Roxy Music's last, and most successful, studio album. "I've had more comments and compliments on this album by far than anything else I've ever done."

When you think just how many hit records Clearmountain has mixed, that's quite a distinction for Bryan Ferry and his band. It's now 21 years since Avalon was released, and Virgin have marked its coming of age with the seemingly obligatory surround remix. In keeping with their policy of hiring the original producer and mix engineer where possible, they asked Clearmountain and producer/engineer Rhett Davies to handle the 5.1 remix. Working from digital copies of the original 24-track tapes, they remixed it for Super Audio CD at Clearmountain's LA studio.

Back In The Day

Both Davies and Clearmountain began their association with the band during 1979's Manifesto album. "They were in the middle of making Manifesto, and the engineer working on it was Phil Brown, one of the house engineers at Island, who I'd learnt my trade through," recalls Rhett. "He had to go into hospital, and they asked me to stand in for a couple of weeks until Phil was well again, and that was it. I kind of got stuck there. We went to America to do some overdubs and mix at Atlantic Studios, and then Bob Clearmountain did a remix of 'Dance Away', and that was the first time that Bob had got involved."

Photo: Piers Allardyce"I had worked with Chic, and that was on Atlantic Records, so I got a reputation over at Atlantic for doing R&B stuff and dance mixes and stuff like that," explains Bob. "The Stones and Roxy Music were interested in more of an R&B sound, and I guess my name must have come up somewhere along the line."

Photo: Piers Allardyce"I had worked with Chic, and that was on Atlantic Records, so I got a reputation over at Atlantic for doing R&B stuff and dance mixes and stuff like that," explains Bob. "The Stones and Roxy Music were interested in more of an R&B sound, and I guess my name must have come up somewhere along the line."

Clearmountain made an impact straight away with his remix of 'Dance Away': "They said they wanted an R&B type of thing, but I remember at the time the drums weren't doing the right thing. The bass drum wasn't consistent enough, so I actually brought in a New York drummer to just play bass drum, and we added some percussion. Then the song wasn't structured right. It was verse, chorus, verse, middle eight. [Legendary Atlantic boss] Ahmet Ertegun came over and he said 'Where's the second chorus? You've got to have another chorus in there.' I didn't know Roxy Music, I'd never met any of them, and I was thinking 'How can you mess with their song?' But we put the second chorus in and they loved it."

Synthetic Grooves

Rhett Davies.Photo: Piers AllardyceDavies, meanwhile, brought with him the experience of working with Brian Eno on groundbreaking albums like Taking Tiger Mountain and Another Green World. As a result, he was able to introduce Ferry and the band to a completely new way of writing and recording their material. "Eno had opened me up to the way of working where you walk in with a blank sheet, stick some white noise down, count one to 100 and then fill in the spaces, and it was great working that way. Sometimes at the end of the day Eno would just turn round and say 'Stick all 24 tracks into Record and get rid of it, I hate it!' — which was tough to do — but most days we'd come out with something. When I started working with Roxy Music and with Bryan Ferry, Bryan had only known the 'let's cut the track with the band in the studio' approach, and I think he was searching for certain feels in his music which he wasn't getting from the studio floor with live musicians. I said 'Well, there is another way of working. We can put down our groove exactly as you want it synthetically, using a rhythm box, and the musicians can then play to that groove.' So, at all times, Bryan had the atmosphere or the feel of the track that he wanted, and we found that a good way of working. The musicians came in and, rather than trying to create something, they responded to the atmosphere that was already on tape."

Rhett Davies.Photo: Piers AllardyceDavies, meanwhile, brought with him the experience of working with Brian Eno on groundbreaking albums like Taking Tiger Mountain and Another Green World. As a result, he was able to introduce Ferry and the band to a completely new way of writing and recording their material. "Eno had opened me up to the way of working where you walk in with a blank sheet, stick some white noise down, count one to 100 and then fill in the spaces, and it was great working that way. Sometimes at the end of the day Eno would just turn round and say 'Stick all 24 tracks into Record and get rid of it, I hate it!' — which was tough to do — but most days we'd come out with something. When I started working with Roxy Music and with Bryan Ferry, Bryan had only known the 'let's cut the track with the band in the studio' approach, and I think he was searching for certain feels in his music which he wasn't getting from the studio floor with live musicians. I said 'Well, there is another way of working. We can put down our groove exactly as you want it synthetically, using a rhythm box, and the musicians can then play to that groove.' So, at all times, Bryan had the atmosphere or the feel of the track that he wanted, and we found that a good way of working. The musicians came in and, rather than trying to create something, they responded to the atmosphere that was already on tape."

Manifesto and the subsequent Flesh & Blood album were both recorded in this fashion, and Avalon proceeded likewise. "We started off down at Phil Manzanera's Gallery Studios in Chertsey. We started with a blank sheet; there weren't any songs. Phil might have had some chord sequences or musical ideas, and Andy would have some tunes that he'd written, which he'd present to Bryan, and Bryan would play around with them to see if there was any work he could do. I would then spent time with Bryan alone, writing. It didn't take that long — we'd go in in the morning and I'd get a groove going to get something happening that Bryan could walk into, and hopefully he'd be inspired by it."

With work well under way on the basic tracks, Davies and the band decamped to Compass Point Studios in Nassau for a month. Here they continued to build up musical backing tracks based around rhythms from a Linn Drum. "The Linn Drum hadn't been around for Flesh & Blood — we were using Roland CR78s and stuff like that — but it was the main rhythm machine on Avalon. Sometimes I'd be programming to a chord sequence and we'd say 'We just need a click track,' and then on other days I'd be driving into work and hear a Talking Heads track or something, and I'd think 'What a great groove that is,' and I would go in and do my version. Then Bryan, Phil or Andy would come in and go 'That's pretty good, let's try...' and it would evolve from there."

Stairwell To Heaven

"When we remixed the Avalon album at Bob's studio in Los Angeles, the biggest task that we had was to recreate the Power Station reverbs," says Rhett Davies. "The first time we stuck it on and we were listening to it over there we both went 'Jesus Christ, there's so much reverb on this!' It was scary, but it fits the mood of the album. The main thing at the Power Station was the stairwell. They had an enormous stairwell which was miked up, and had an unbelievable sound. You'd put anything through it and you'd just go 'Yeah, we've got to have that.'"

"It was a magnificent-sounding long reverb," agrees Bob Clearmountain. "It was a 75-foot stairwell with a beautiful sound, and trying to recreate that was difficult. It was about four seconds, depending on how humid it was that day. I think we had a big roll of fibreglass if we wanted it smaller, but for that record we just kept it wide open. It would change a lot depending on the weather. If it was a really humid day you'd get an additional second or so on the reverb time. The more moisture in the air, the better the sound can travel and the further it goes — moisture's a really good conductor of sound. We had a couple of AKG 451s in an X-Y pattern in the middle of that space on a tall mic stand, it was very stereo, and the speakers were two flights down pointing downwards, so there was no direct sound at all. It was an interesting sound, because the top end would gradually roll off before the middle. I've studied it quite a bit, because I used it so much in the '80s, so that made it easier to duplicate, because I knew that if I put a mid-rangey reverb at four seconds and then a brighter reverb at two seconds I could make it work."

Recreating the Power Station's stairwell might sound like the ideal job for a sampling reverb such as Yamaha's SREV1, but there's a snag: it doesn't exist any more. Instead, it took a lot of hard work from Bob Clearmountain. "I had four different digital reverbs, plus I have two live chambers in the studio — they're pretty small but they're quite nice-sounding — so I just got different combinations and worked for hours to make it sound really similar to the Power Station reverb. What was interesting was that on the first track that we mixed, I was able to do that, and then on the next track, I figured 'Oh great, now I have that down, I'll just use it again' — but it would be totally different. There'd be some other instrument, I'd put it in there and it wouldn't sound anything like the original. Then I'd have to go through the whole thing again, I've no idea why.

"Instead of thinking literally about the size and shape of the original, which I knew quite well because I helped to build it, it was more a question of imagining the space in the particular piece of music. I thought of it as an imaginary environment, and it was a lot easier to duplicate that way. I have a couple of Yamaha boxes and some Lexicon boxes and knowing what they do and how they react to particular sounds, I just moulded it. Like a painter would know that certain colours give you a certain type of effect."

Even when working in surround, however, Clearmountain tends to stick to mono or stereo reverb patches. "I don't really use a four- or five-channel reverb. I've tried them, and they just sound bland to me. It's like a synthesized four-channel effect that sounds like it's everywhere instead of being somewhere. I'll use two PCM70s that are stereo front and rear left, and front and rear right, and then I can cross those, send one thing from the left over to the right side, or localise things. You can do a lot more with creative use of mono or stereo effects in surround. It gets a lot more interesting."

Finishing Touches

By the time band and producer headed to the Power Station in New York to finish the album with Bob Clearmountain, it was still a long way from being complete, lacking as it did lyrics, vocals, and live drums. "It was all done either with a drum machine or with drums that they wanted to redo," says Clearmountain. "A couple of the songs had the final drums on them, but the rest of them we overdubbed Andy Newmark a couple of days before we mixed, and then we did percussion as well, with Jimmy Maelen. And Bryan was doing vocals right at the last minute, as well. He'd only just written the lyrics. Most people didn't work like that. The drums were usually the first thing, at least back then!"

"On a couple of tracks, on songs like 'India', the Linn Drum parts are still the main thing," adds Davies. "To say we replaced them on the other tracks isn't exactly true. On some we did; Andy Newmark was drumming to a full-sounding track with a full drum program on there, so it freed him up to a large extent. In some cases it was a straight replacement — he'd replace that groove and add a feel to it. In other cases we would keep the more percussive components of the Linn pattern in the final mix, and just take out the kick and snare and hi-hat, which would be replaced by the real drumming. You could never say what combination was going to work. Sometimes Andy would go out and just do tom and cymbal overdubs against what we had.

"By and large, if we recorded a kit, we used it. We'd generally get a full kit pass, and then we'd do additional tom fills and overdubs. We got a great drum sound at the Power Station — it was a totally wooden room to mic up in, and that's part of the sound of that record. We did use a room sound, it wasn't all close-miked. We weren't really worried about the separation; if it felt right and sounded right, that was good enough."

Beginning with musical ideas and grooves rather than complete songs had freed Roxy Music from some creative restraints, but it also had its down side. Unsurprisingly, a fair amount of material went to the wall. "We would cut a lot of stuff that never got used, a lot of trials that Bryan just couldn't work into songs," says Rhett. "If you're just starting with an instrumental, there's going to be times when you just think 'I can't write a song for this.' When he eventually did write a song, we'd then have to slow the tape down drastically, or speed the tape up drastically to get it to a key that he could sing it in. Most of the time we'd get by with it like that — when we went to mix the album at the Power Station we were talking about varispeeds of a whole tone, which they'd never heard of before. They had to realign the machines.

"With the 'Avalon' song we had to recut the entire song right at the end of the album. We were actually mixing the album, and the version of the song that we'd done just wasn't working out, so as we were mixing we recut the entire song with a completely different groove. We finished it off the last weekend we were mixing. We put some percussion on and some drums on, and then on the Sunday, in the quiet studio time they used to let local bands come in to do demos. Bryan and I popped out for a coffee, and we heard a girl singing in the studio next door. It was a Haitian band that had come in to do some demos, and Bryan and I just looked at each other and went 'What a fantastic voice!' That turned out to be Yanick Etienne, who sang all the high stuff on 'Avalon'. She didn't speak a word of English. Her boyfriend, who was the band's manager, came in and translated. And then the next day we mixed it."

"The record was so well produced and well put together that it wasn't difficult to mix at all," says Clearmountain. "In fact, for the most part we did two songs a day — and that's an eight-hour day, because the Power Station at that time wouldn't let you lock out the studio. They always insisted that each room had a day session and a night session, so you had to start from scratch the next day."

Surround At Last

On its release in 1982, Avalon soon took up residence at the top of the UK charts, and also became the band's most successful album in the US. The CD version has already had the remastering treatment at the hands of Bob Ludwig, who'd mastered it the first time around; and, as one of the most important albums in Virgin's back catalogue, it was an obvious candidate for remixing into surround. "The interesting part to me was that when we originally mixed it in stereo, I was thinking that it should be in surround," says Bob Clearmountain. "I was wishing that I had more channels to pan things to, and I imagined it being like that. It's that type of a record, it really lends itself. When surround first started one of the first things I thought was 'I'd love to mix Avalon,' because I knew there were so many interesting production elements on the album."

Rhett Davies was more apprehensive about the project: "When I was first approached by Sony with the idea of remixing Avalon into surround I had my apprehensions about it, I must admit. I thought 'You don't f*ck with things like that.' I was a little worried, but when it was confirmed that the original stereo mix would be on the SACD as the first layer, then I thought of it more as a challenge. I thought 'If people buy it, they'll get the original stereo mix in the best possible quality, and we've got a chance to see what we can do with it in surround, which will be fun.'"

The ideal would probably have been to have worked from the original analogue multitracks, but these had been recorded on the wrong type of Ampex tape, and were in no state to be used 20 years later. Fortunately, however, they had been baked and their contents transferred to Sony digital open-reel tapes before the deterioration became terminal. From the Sony machines, the tracks were mixed into surround in the analogue domain using Bob Clearmountain's SSL mixer, with the surround mixes being recorded onto Sony's dedicated multi-channel DSD recorder.

"I don't think the sound quality in DAWs is as good as an analogue desk," insists Clearmountain. "It might not be true of the more high-end digital systems like the new SSL or Euphonix desks, but Pro Tools is still not very high quality. The converters in the new HD systems are a little bit better, but the mix buss is still fixed-point. As soon as you do any processing in Pro Tools you're degrading the signal and I hear that. When you do level changes, pretty much anything, it tends to degrade and you lose depth, you can't really get that type of depth perception that you get from a really good analogue desk like an SSL G Plus or a J-series. You notice it right away, as soon as you push the faders."

Keeping It Tidy

Photo: Piers Allardyce

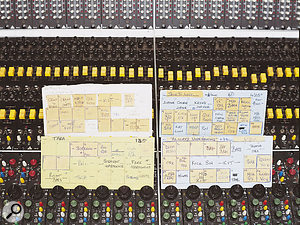

Photo: Piers Allardyce Some of Rhett Davies' original track sheet cards for the Avalon album. Photo: Piers Allardyce "These are my original track-sheet cards for Avalon," says Rhett Davies, producing an evelope full of battered pieces of card, many of them thick with layers of gaffer tape. "I used to cut gaffer tape as I would comp things and bounce things and move things around so I'd got them just how I wanted them, then that track would get moved, and some of the gaffer tape is a quarter of an inch thick! To me, losing a generation of quality of something on tape wasn't of prime importance. Getting it to sound right was. If it meant that I had to lose quality to get the sound that I wanted then I wasn't frightened to do that. I'm a very tidy person, and I like to have everything organised and cleaned up. If there's stuff we don't want, erase it, get rid of it. Don't have it sitting around creating confusion later on. Once we got into 48 tracks, as we did on a couple of the songs, then you've got some decisions and choices. When we were remixing it, Bob and I had to go back and check the record a few times, and think 'Oh, we cut that out in the second verse, that isn't there.' That's when it started to move towards keeping everything, which makes it a lot more complicated and time-consuming."

Some of Rhett Davies' original track sheet cards for the Avalon album. Photo: Piers Allardyce "These are my original track-sheet cards for Avalon," says Rhett Davies, producing an evelope full of battered pieces of card, many of them thick with layers of gaffer tape. "I used to cut gaffer tape as I would comp things and bounce things and move things around so I'd got them just how I wanted them, then that track would get moved, and some of the gaffer tape is a quarter of an inch thick! To me, losing a generation of quality of something on tape wasn't of prime importance. Getting it to sound right was. If it meant that I had to lose quality to get the sound that I wanted then I wasn't frightened to do that. I'm a very tidy person, and I like to have everything organised and cleaned up. If there's stuff we don't want, erase it, get rid of it. Don't have it sitting around creating confusion later on. Once we got into 48 tracks, as we did on a couple of the songs, then you've got some decisions and choices. When we were remixing it, Bob and I had to go back and check the record a few times, and think 'Oh, we cut that out in the second verse, that isn't there.' That's when it started to move towards keeping everything, which makes it a lot more complicated and time-consuming."

Mixing For The Future

Analogue mixing may preserve better sound quality, but working on a desk that's not designed for surround can be very restrictive. However, Bob Clearmountain had already worked out how to make his SSL G-series suitable for the task. Forty years ago Bill Putnam had the foresight to record in stereo at a time when most record labels were only interested in mono; now Clearmountain is taking the same approach to 5.1 surround. "Everthing I've mixed for the last two years I've done also in surround, even though it's usually just stereo mixes that people want," he explains. "It was actually my wife's suggestion. A few years ago she said 'You should be mixing everything in surround.' I was like 'My God, how am I going to do that?' But I sat down and thought about it for a minute and I realised that there were some factory modifications that I'd had done when I ordered my SSL desk which facilitated being able to do both at the same time quite easily.

The SSL G Plus desk in Bob Clearmountain's studio has had several modifications to make it more suitable for surround mixing. Photo: Piers Allardyce

The SSL G Plus desk in Bob Clearmountain's studio has had several modifications to make it more suitable for surround mixing. Photo: Piers Allardyce

"It has what they call the Bluestone mod. I don't know where they got the name from, but it's actually more for facilitating the use of eight-channel headphone mixers for musicians, so that each musician can do his own eight-channel mix. It's a 32-mix buss console and they've taken the last eight and sent them from a send on the channel. So instead of a front-back panner, they've converted that into a send to these eight additional busses. Normally, there's a bunch of effects I would send from the multi-channel busses like delays and additional reverbs and stuff like that — I use them as aux sends off the small fader — but for the surround mixes I'm using the multi-channel busses for the surround matrix, for getting to the surround channels, so I no longer have that to use for additional effects. So this mod gives me eight additional aux sends really, that's what it amounts to.

"The desk has eight stereo patchable VCAs, which I usually don't use very much, but through a very simple mod I was able to link the stereo compressor to those eight patchable VCAs, and then I use those for my six-channel mix compression. So as long as I have a stereo mix running, the six-channel mix will compress the same. It's like a side-chain off the stereo compressor. It's a really simple mod, you just need a little buffer amplifier in there. I had been trying to find a really good six-channel compressor, and I couldn't find an analogue one anywhere. There were only digital ones, and I didn't really want to go through another digital process. I compress my surround mixes the same way I compress the stereo mixes, just because I like that particular sound, it makes the mix sound more exciting to me and more fun to listen to — but not to the point that some mixers do it, and probably less than if I was going for a strictly commercial single. On Avalon I didn't compress it very much, not like if I was doing the next Kylie Minogue single or something like that."

One potential limitation remains: with only faders and pots to control pan positions, smooth motion panning around the surround field can be difficult. "I don't do a lot of that because I sometimes find it distracting," says Clearmountain. "Occasionally I will do it, and there's a few ways of doing it. One is paralleling to a bunch of different faders and just assigning them to different channels — turning one down and turning the next one up. The other way is actually to send something into Pro Tools and use Pro Tools as a panner. I'd rather not do that, but at a pinch that will work — I take a four- or five-channel output out of Pro Tools and then use the panner in there, then I can program it any way I want. I tend to do more things with cascading delays. On Avalon there's a few places where you'll hear something in the left rear and it'll delay to the left front and then to the right front and the right rear, things like that. It gives you more of a feeling of spaciousness, instead of just having things moving around.

"At first I was really reluctant to use the centre channel, because whenever I put something just in the centre, it seemed to mess the vibe up. There's something about the phantom centre in stereo, there's an illusion of some sort there that is somewhat seamless, whereas if you put the vocal right in the centre speaker, all of a sudden it sounds like it's coming out of a speaker, rather than sounding natural. What I usually do is I'll put vocals and drums and things like that in all three front speakers, but less in the centre. But then occasionally I'll put it more in the centre. Putting it at the same level, you tend to get phase problems depending on how the speakers are set up. And then occasionally I'll have the vocal in all three speakers, and put the lead guitar or acoustic guitar just in the centre, so they're both in the centre, but somehow in different places, there's a different perception of depth."

Printed Matter

One feature of Rhett Davies' production style that surprised Bob Clearmountain when they first worked together was his willingness to print effects to tape with instrument recordings. "Generally speaking, and this applies to Avalon, if we were working on a particular sound and that sound had a delay or a reverb, I would print that with the signal. I love delays. We used the Roland Chorus Echoes a lot, and I still do today, I love them. Quarter-note triplet delays are my favourites. Anything that creates cross-rhythms is what I was always looking for, so if we were working with a rhythm box, I'd always be experimenting with delays, just to create something more than the plain thing that was there. Obviously it depends on the instrument, but if you're talking about basic backing-track instruments then you're trying to create something.

"My concept was always that anybody could put the track up and push the faders up and it would sound as it's supposed to sound. When we mixed Flesh & Blood, Bob couldn't believe it, because nobody printed delays with the signal. If it was something like the lead vocal, I'd print that to a separate track, but we were still working on 24 tracks, and if it was a guitar and that was part of the sound it got printed. Roxy enjoyed working that way, because there's nothing worse than thinking 'It doesn't sound as good as it did last week, what's different? I'm sure that's the same setting.' This way, it's always there, and it makes a faster way of working. I could put a track up in a minute and it was ready to do an overdub, so if we had musicians coming in that we wanted to try on two or three songs, it was really fast just to change the tape, and the song was ready to go. I also always used to try to keep an instrumental rough mix on tape as a working mix, so you could just whack up two faders and it was there."

True To Life

"The way that Bob works, which is nice, is to build up the stereo mix first," explains Rhett Davies. "We A/B'ed it against the original album and tried to get it as close and as true to the original stereo mix as possible before we even thought about the surround. Once we'd got it to that stage, we would then open up the surround and experiment with instrumentation and panning. Bob and I said 'We're not just going to put a little reverb in the back speakers, we're going to make this something special. We're really going to play with the medium.' And we were both blown away by how well the Avalon album worked, technically, in surround. It seemed to use that it was made to be mixed in surround. We made it playful, but I think in keeping with the original record. We had reverbs in the back speakers as well as delays, but also we actually put instruments directly into the rear speakers as well."

"My surround mixes are basically very similar to the stereo mixes, except there's things panned in different places," says Bob. "I try to make them a bit more interesting, but it's actually the same balance, all the same rides and the same EQs. It's just that the effects are expanded and their placement in surround is discrete. And there's a subwoofer channel.

"It was as fun as it was difficult for me, and interesting, because I really had to think back 20 years. We had no notes, we were lucky to even have the multitracks. All I had was my memory and what I could hear from listening to the stereo mix. We had the original stereo mixes lined up with the multitrack, and it was a matter of thinking 'OK, what did I do there, how did I get that particular effect?' And then I'd have to think back to what I might have been doing 20 years ago. We did try to duplicate it as much as possible.

"At one point I thought 'Maybe we should just go in a different direction,' but when I did that, it didn't sound like the right album — even though if I had mixed that album today, I probably would have done it differently. There probably wouldn't be quite so many effects, not as much reverb or delay. But when I tried to do that it didn't sound right. I know the album well because I've listened to it a lot, and I'm sure the fans, people who know the record would find it uncomfortable because it would be different."

Bob Clearmountain's preference for mixing in the analogue domain is reversed when it comes to choice of recording medium. "We mixed originally to analogue, and I think digital nowadays is a better format to mix to. I know people like analogue, but I think it actually hurt it a little bit. I think it sounds better not going through that analogue tape stage and losing that extra generation. It makes it sound a bit more distant, it's like a very thin curtain in front of everything. For some things I think that helps, but for a record like Avalon I don't think it does."

No Control

"The manufacturers of consumer gear should put a really obvious button on their systems saying Music," says Bob Clearmountain. "Most of the home systems are designed for movies, and have extra DSP built in to create some sort of theatre ambient effect, and they have automatic level controls. Those are the last things you'd ever want for listening to music. A lot of systems default to having them switched on, which means that if you play music, you get one big bass drum or tom-tom, and it kicks the level right back. It's usually buried 10 menus deep. But how are people supposed to know that? It was tough for me to find on my Sony. You get the general public out there and they're lucky if they get the speakers in phase. How are they going to know to do that?

"You really don't have much control over how things are played back. There's this whole bass management issue, which I still don't quite understand. I just know that on my Sony receiver at home, I noticed that if I didn't put anything in the LFE channel, the system made up its own LFE, and it sounded terrible. It would just take some kind of sum of the other channels and create a subwoofer channel. But when I did use the LFE channel it was just what I put in, and it sounded much better. A lot of people told me 'For music, don't put anything in the LFE channel, that's only for movies.' But then I started doing it and when I played it on my system it just sounded right, when I had control over it. But depending on how you have your system set up, that could be wrong. I just put stuff in the LFE channel and let the mastering guy worry about it!"

More Than This?

Following the release of Avalon, nothing was heard from Roxy Music for almost 20 years, but the band recently reformed for a live tour, which was overseen by Rhett Davies as musical director. A live album from the tour has already seen the light of day, and Roxy's management haven't ruled out the possibility that a new studio album might emerge in the future. In the meantime, fans with Super Audio CD players can enjoy the fruits of Davies and Clearmountain's labours. "I feel that this is actually an extension of the original experience of the album," concludes the latter. "I sure hope people like it..."