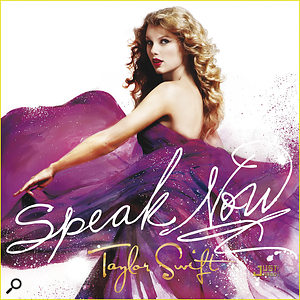

Taylor Swift has become country music's biggest mainstream star, thanks in part to a stellar production team. Producer Nathan Chapman and mixer Justin Niebank lift the lid on Swift's latest hit album, Speak Now.

Nathan Chapman at his Pain In The Art Studio.Photo: Emily Mueller

Nathan Chapman at his Pain In The Art Studio.Photo: Emily Mueller

In early 2006, Taylor Swift was an unknown 16‑year old with a good voice and a talent for writing songs. Her rise to the top since then has been, well, swift. Her eponymously titled debut album was released in October that year, and became a monster hit in the country market. Follow‑up Fearless, released in November 2008, has sold more than 10 million copies worldwide, propelled her to the top of mainstream charts around the world, and spawned hit singles like 'Love Story' and 'You Belong With Me'. It made her, at age 20, the youngest person ever to receive the Grammy Award for Album of the Year.

The huge pressure that must have resulted from all this appears to have rolled off her like water off a duck's back, for her third album, Speak Now, released in October 2010, appears to be on its way to become as successful as its predecessor. It sold more than one million copies in the first week after its release, and has already generated one major hit single, 'Mine'. At the time of writing, the second single from the album, 'Back To December', was near the top of the US charts.

Chemistry

When she was first signed, Swift's record company Big Machine sent her into the studio with some big‑name producers. This, however, resulted in a serious case of 'demoitis', Swift believing that her original demos had a better feeling than the newly recorded tracks. The record company must have felt that she had a point, for the complete unknown responsible for these demos was duly invited to produce three album tracks. By the time he was done, he was tasked with producing the whole album (minus one song), leading directly to the above‑described results.

The unknown in question is Nathan Chapman, and four years on he's regarded as one of the biggest hitters in Nashville. Having not only produced Swift's Fearless and Speak Now and won two of Fearless' four Grammy Awards, he has also produced The Band Perry, Jewel and Jimmy Wayne, and has had one of his songs recorded by Martina McBride. At the relatively young age of 33, he already has an astonishing three decades of music industry experience behind him, the reason being that his parents are Christian singers and recording artists, and as a result he's been in and out of studios and on the road from a young age. His web site shows him as a 10‑year‑old at a mixing desk with a track sheet, looking very serious. On the phone from his studio in Nashville, Chapman comments: "As a child, I was fascinated by the recording process, and by the time I was 14 my Dad would play me songs he'd written, and I would tell him that I knew exactly what the whole band was supposed to do. He was like: 'Oh, you're a producer.' I would say, however, that my first thing is to be a guitar player.”

Chapman appears to have slightly overdosed on music and the recording process at one stage, because in the late '90s he escaped to Lee University in Tennessee to do a degree in English. Meeting his wife Stephanie, a singer‑songwriter, in 2000, put him back on the music trail, and for a number of years he produced demos for her and others in his own modest, Nuendo‑driven facility located "in a shack behind a publishing company in Nashville”. In 2005, a fellow songwriter called Liz Rose was impressed enough with the demos the Chapman couple had created to ask Nathan Chapman whether he was up for doing some demos for a promising young singer‑songwriter she was writing with, one Taylor Swift.

"Taylor and I made the demos for the first album at my then studio,” elaborated Chapman, "with me playing all the instruments. When I was given the job of actually producing three songs, and then almost the whole of the record, we took these demos into a few professional studios and tracked them there with a small band. For the next album, Fearless, we went into a professional studio without me having heard the songs before. Taylor played me her songs right there and then, while the band was waiting, and I charted them and we cut the tracks live in the studio, with me playing guitar, plus a bassist and a drummer, and Taylor singing live. We added the other instruments as overdubs.

"With Speak Now, we deliberately went back to our initial way of working together. We had an unlimited budget, and could have gone and recorded the whole album in the Bahamas, used any studio we liked and whatever musicians we wanted. But we decided to bring it back to the basics on purpose, because we wanted to keep it about the music and our chemistry. The second album was easier because we were coming off the momentum of the first album, and we simply continued the artistic track that we were on. It sold like crazy and won all these Grammy Awards and we're very proud of it. After all that, we wanted to keep ourselves out of a place of failure, and not try to over-compensate for the pressure we were feeling for a follow up to Fearless. That's why we stripped it down and made the demos first. Taylor came to my studio and I played all the instruments on the demos, and because I have a good vocal booth, her demo vocals ended up being the vocals you hear on the record. After finishing the demos, we went out to different studios, and tried different combinations of engineers and musicians to replace some of the elements of my demos, mostly the programmed drums, and to do additional overdubs.”

Real Emotion

Justin Niebank, in his own room at Nashville's Blackbird Studios.

Justin Niebank, in his own room at Nashville's Blackbird Studios.

Chapman and Swift's working method comes across as a straightforward and sensible strategy for avoiding performance anxiety and corresponding creative obstacles, and it clearly paid off. In the process Swift stepped up a gear, for while she co‑wrote a substantial number of the songs on her first and second albums, mostly with Liz Rose, she wrote all the songs for Speak Now by herself, displaying a remarkable degree of self‑confidence for someone so young. Chapman's contribution is equally impressive, given that he says that he's responsible for playing "probably 60 percent of the music on the album, including 90 percent of the guitars.” He also turns out to be a very quick engineer and arranger, playing, arranging, and recording the demos for each song in just a few hours at his Pain In The Art Studio in Nashville. The demo for 'Mine' apparently took less than five hours to record, and sounded, according to Chapman, "almost identical to the record. After that we worked on the track for another four months, off and on, and spent $30,000 to make sure it sounded perfect in the real world.”

So how on earth does he manage to create record‑quality demos in just a few hours? And why then spend another $30,000 perfecting them? The whole process began, apparently, with a particularly liberal approach to coaching Swift in songwriting. "Taylor is a great songwriter, and there's not much I have to do on that front. I'm not afraid to be OK with that. Some producers may be uncomfortable with not giving an opinion, they don't want to appear useless. I'm not like that. I want to capture her gut instinct of her playing her songs on her guitar, because nine out of 10 times that's the right way to go. It's exciting when she sings a song with her guitar. And because the environment at my studio is pretty laid‑back, I usually get that. If we do make changes in the songs, like cut an instrumental section that appears two times, or rearrange things in other ways, it usually happens later on.

"When I work with Taylor at my studio, it's just she and I. I do the engineering myself. It's not hard to do. I work in Logic or Pro Tools and have a Digidesign C24 control surface, and I use Focal Solo 6 monitors, which are my favourites, and [Yamaha] NS10s, and a couple of racks of outboard. I have all my different recording chains plugged in and ready to go. I don't ever have to reach up and turn a knob. It's a bit like Chris Lord‑Alge, who doesn't turn the knobs on his compressors but just moves patches [to use a different compressor instead]. I have three or four microphones that I swing into place when I need them and swing back when I don't. Nathan Chapman's approach to recording instruments is refreshingly simple: "I have three or four microphones that I swing into place when I need them and swing back when I don't.” Because I've worked this way for so long, playing all the instruments in demos and recording everything myself, I don't really know how to work any other way. Pressing buttons keeps me focused on the project, and as soon as I step out of my studio, I'm worthless!” he laughs.

Nathan Chapman's approach to recording instruments is refreshingly simple: "I have three or four microphones that I swing into place when I need them and swing back when I don't.” Because I've worked this way for so long, playing all the instruments in demos and recording everything myself, I don't really know how to work any other way. Pressing buttons keeps me focused on the project, and as soon as I step out of my studio, I'm worthless!” he laughs.

"So Taylor comes in, and plays me a song, and I chart it while listening to her. I then tap out a tempo, she hands me her guitar, I go into a recording booth, put on headphones, start the click‑track and hit record. She's hearing what I'm doing and singing along while she's in the control room, so I know where I am in the song. After that, I program the drums, usually using [Toontrack's] Superior Drummer in Logic. I play the drum parts on my Roland Fantom G6 keyboard, and then quantise. I then play the fills that I want to complete the drum part. After this I'll put down a bass part, and at this point we make sure we're really OK with the tempo and that we love the arrangement. I may add an electric guitar to make the track bigger, and then she'll go into the vocal booth and she'll sing the song three or four times. We may do a little bit of comping, but she executes these songs really well, and I don't want to mess with her takes too much. The audience wants to hear someone sing with real emotion. From there we'll listen to what we have and we'll maybe add some vocal harmonies and guitars, and I do a quick mix and she's out of the door.”

Boring Bits

Chapman stresses that Swift's co‑production credit is "not a vanity credit. We were really a team, very collaborative. There are parts of making a record that are boring, and she was there the whole summer, including all the boring bits. She'd have opinions on drum sounds, and everything that we did. She also played some acoustic guitar, like the intro part of the song 'Speak Now' and in a few other songs. The song 'Never Grow Up' is just she singing and I on acoustic guitar. We recorded ourselves live. That song probably happened in two hours.”

With regard to his signal chains, Chapman says "I recorded Taylor's voice with an Avantone CV12, which I also used on Fearless, going into a Martech MSS10 mic pre, and then a Tube‑Tech CL1B compressor. All of Taylor Swift's vocals on Speak Now were recorded at the demo stage, on Nathan Chapman's Avantone CV12. For acoustic guitar I use a Neumann KM54, going into an API 512 preamp, going into a [Empirical Labs] Distressor. I recorded my own harmony vocals with a Shure SM57, also going via the API and Distressor. I use the same mic and signal chain for recording electric guitars, though I have to say that I only used real amps for about 40 percent of my parts on the album. For the other 60 percent I used the Logic 9 Amp Designer. I've used plug‑in amps for a while, like the [IK] Amplitude and Digidesign [now Avid]'s Eleven, and I particularly love the sound of Amp Designer. For bass I used an Avalon VT737 direct signal path preamp. There are three or four tracks on which my demo bass survived, 'Dear John' being one of them. For going in and out of my DAW, I used the Apogee AD16X and the DA16X, although I just got the Symphony I/O, which sounds great. I also have the Cranesong Avocet monitor system.”

All of Taylor Swift's vocals on Speak Now were recorded at the demo stage, on Nathan Chapman's Avantone CV12. For acoustic guitar I use a Neumann KM54, going into an API 512 preamp, going into a [Empirical Labs] Distressor. I recorded my own harmony vocals with a Shure SM57, also going via the API and Distressor. I use the same mic and signal chain for recording electric guitars, though I have to say that I only used real amps for about 40 percent of my parts on the album. For the other 60 percent I used the Logic 9 Amp Designer. I've used plug‑in amps for a while, like the [IK] Amplitude and Digidesign [now Avid]'s Eleven, and I particularly love the sound of Amp Designer. For bass I used an Avalon VT737 direct signal path preamp. There are three or four tracks on which my demo bass survived, 'Dear John' being one of them. For going in and out of my DAW, I used the Apogee AD16X and the DA16X, although I just got the Symphony I/O, which sounds great. I also have the Cranesong Avocet monitor system.”

Chapman uses the Endless Audio CLASP System in his studio. Described in some circles as "the biggest breakthrough in recording technology in years”, it provides a seamless way of using a large‑format multitrack tape machine as a front end when tracking to a computer‑based DAW. Chapman: "All lead vocals and electric and acoustic guitars were cut to my 1979 MCI JH24 tape recorder, and then synchronised with Logic or Pro Tools using my CLASP system. The CLASP system allows you to record and play back from tape and your DAW all in one movement, without any latency whatsoever, which is great for performing. If you listen to 'Mine', you'll hear some tape hiss in the intro vocal. I like that; it's fun.”

Artistic Vibe

This composite screenshot shows most of the Pro Tools Session for 'Mine' (various effects and group tracks are omitted at the bottom). Tracks are colour‑coded and organised by instrument. From top: drums (brown), bass (green), guitars (blue), lead vocals (red) and harmony vocals (more green).

This composite screenshot shows most of the Pro Tools Session for 'Mine' (various effects and group tracks are omitted at the bottom). Tracks are colour‑coded and organised by instrument. From top: drums (brown), bass (green), guitars (blue), lead vocals (red) and harmony vocals (more green).

Despite Chapman's obvious enthusiasm for the CLASP system, he emphasises that he's not an analogue freak, and in general plays down the importance of his gear, despite endorsement deals with Logic, Avantone, Apogee and PRS guitars. "I'm not much of an engineer,” Chapman says. "I simply use whatever is in front of me. I don't know, for example, whether the Martech or the other stuff I have is the best. I simply have it in the house and I plug it in. I also would not describe myself as an analogue guy at heart; I don't use tape on 90 percent of the projects I do, but when I do need it, the MCI is great. Part of the reason for using it on the new Taylor album was because many of the songs have a retro vibe to them, so I was trying to honour that. If you want the sound of tape saturation, you need to use tape. Using tape is a creative tool, I enjoy using it as much for sonic reasons as for the artistic vibe: it's cool to have the energy of a tape machine running in the room while working!”

With regards to his dual Logic/Pro Tools setup, Chapman explains that "I probably work 50/50 with them. Logic is a programmer's dream, and Pro Tools doesn't handle virtual instruments well. Here's how I look at it: Logic is for creative people like composers and songwriters, Pro Tools is for engineers. Logic has everything right there for programming, and I'll use it when I want to create loops and keyboard parts and am throwing out ideas. But if I'm wearing my engineering hat, recording audio and trying to get the right sounds and so on, I'll use Pro Tools. But I love Logic. If I'm working on Pro Tools I may bring things back into Logic if I want to create loops and keyboard parts. The keyboard stuff I record on my demos is usually done in Logic, using Logic soft synths, though some of the stuff is done with the Roland Fantom. 'Mine' was recorded in Pro Tools, because it was very much a guitar song, but most demos for Speak Now were done in Logic. I do the rough mix in the box, in whatever platform I started the song in, using plug‑ins from Digidesign, Waves and Sound Toys. Pretty normal stuff.

"A pop artist would probably release what we'd done after five hours, but country artists don't want to hear programmed drums, they don't want to hear fake stuff. So once we had recorded the demos, we would book whatever studio we wanted for each song, to replace the drums, in many cases the bass, and to add whatever overdubs we envisioned, like fiddle, keyboards, percussion and strings. After we got the demos right, we opened it up and allowed ourselves to spend money and cut a big record. You can really blow it at that stage if you have too much time and too much money, but we were very intentional and very disciplined about that, and I think it paid off. The main decisions were made in the demos, but many small details still needed filling in.

"With regard to the drums, the parts we wanted the drummers to play were dictated by the demo. I wanted live drums purely for the sound and the energy. It was more about the performance and the engineering than figuring out what to play. I was pretty much like a classic version of the arranger. So we'd pick a studio, and an engineer, and a drummer, and we'd go and cut the drums on several songs at a time. I did that process with engineers like Chuck Ainlay, Justin Niebank, Chad Carlson and Steve Marcantonio. Steve cut the drums on 'Mine' at Blackbird Studios in Nashville, with Shannon Forrest playing drums. We tried several bassists until we had a bass part that worked, which was played by Amos Heller, of Taylor's live band. In Nashville, it's rare for a road musician to be on the record, but he earned his way into this record by kicking ass. In fact, all Taylor's road musicians played some parts on the album, which was important for me and her.”

Great Balance

Three‑time Grammy‑winning Justin Niebank is one of America's highest‑profile mixers, engineers and producers. He engineered the drums on a few tracks on Speak Now, and mixed the entire album, having also mixed the whole of Fearless. "I'm OK with mixing,” elaborates Chapman, "but I'm more of an emotional mixer. My mixes feel good to me, but I know that Justin's mixes will sound good everywhere. Like me, he has that feel‑good side, and he reads my mind and hears tracks the way I hear them. But we don't only think alike from an artistic point of view, he's also a great technician, who is amazing with balance and tone and making sure that all the frequencies are in the right place.”

Speak Now was mixed in Niebank's room at Blackbird Studios, in Pro Tools. "He mixed Fearless on his desk,” explains Chapman, "but for Speak Now we had to mix 17 songs in three weeks, and I knew that I would want to go back to tweak some of the songs we had mixed earlier, and I did not want to have to recall the mixing board every time. There just wasn't time for that. But we did use the Dangerous 2‑Bus because we wanted analogue summing.”

"We A/B'd the Dangerous,” Niebank continues, "and it's one of these things where you can sit in front of a pair of studio monitors and say, 'OK, it sounds wider and brighter and has more depth,' and that's fine. But does the average person listen to music like that? No, they listen to something that communicates with their hearts, and that, ultimately, is what mixing is about. We felt that sending the mix through the Dangerous sounded good, and it was maybe taking a little bit of the load off the computer. It also allowed me to use my API compressor and the Nightpro EQ3D over the two‑mix, so that pleased me. And I mixed to half‑inch, which is like putting a filter on a camera. It's processing, and basically a sound. I always immediately transfer the half‑inch mix to hi‑res DSD digital, to retain the transients as much as possible.”

Moving on to describing his actual mixing approach, Niebank explains "The challenge of any modern mix is the amount of tracks that you work with, which is very different from the days when you could only fit 23 tracks on a tape. Nowadays you have tons of things and you have to try to figure out how to fit them all together. The most important thing in this respect is to get into the mindset of the people who created it, you have to rewind to their moment of inspiration when they created the song, and see if you bring out the original spirit of their creation. For this reason I love getting a rough mix. There are times when people don't want me to hear the rough mix, and say, 'Go with your gut.' That's fine, but as a mixer I prefer to be part of the whole chain of events. One listen is worth more than a thousand words, and it's nice to hear where they left off. Sometimes people have a great rough, and it's tough to beat it. I like that challenge.

"I prefer it when people send me a Pro Tools file with consolidated files that are cleaned up and together. That doesn't happen all the time. I get a lot of stuff that requires my assistant to spend time going through it and cleaning things up and doing crossfades and things. Sometimes people simply send me the file as it was immediately after their last overdub, and if there's too much to suss out, I'll send it back to them. I'm an intuitive person, and if I have to choose the right vocal take, I'm not doing my job. You have to give me what you're passionate about, and then I can react to that and take it to the next level.

"I don't have a set procedure for mixing. After listening to the rough mix, I'll throw the faders up and I'll listen to everything and start getting a feeling and a handle on the music. If the rhythm is crucial and the song needs power, I'll start with the drums and then the bass. With other songs I'll start with the vocals and acoustic guitars. Sometimes I won't put the bass in until the very end. I work pretty fast. I'll get the lead vocal up and I'll slap stuff in. I don't get precious about individual sounds at first, unless I hear something that requires real surgery. I work with people who know how to record, and my job is less about getting every little thing to sound right as it is about getting a great balance. A great balance will often kind of mix itself. I don't like to over‑tweak or geek. To me that doesn't necessarily make things better, but rather tends to make things sound more processed. I'm also not afraid to pull all the faders back down again if it doesn't work. That's too great a hurdle for many engineers: but if necessary, don't get precious, and start over. I can do five different mixes in 15 minutes, just trying to find a balance that communicates the song!”

'Mine'

Universal Audio's UAD 4K Buss Compressor was used across the final mix. Written by Taylor SwiftProduced by Taylor Swift & Nathan Chapman

Universal Audio's UAD 4K Buss Compressor was used across the final mix. Written by Taylor SwiftProduced by Taylor Swift & Nathan Chapman

Self‑explanatory

Justin Niebank: "Because Nathan is such a good arranger and plays and arranges to the spirit of the vocals, his demos are more self‑explanatory than some other records that I work on. Interestingly enough, I'd done some kind of pre‑mix of 'Mine' for a video thing, with the original drums and bass, and Nathan and Taylor were like: 'This is cool, but we want to go a little bit more for a power approach.' So by the time it got to the final mix they had rerecorded the bass and the drums and it sounded great. Because they really wanted power on 'Mine', I started with the rhythm section and after that brought in the lead vocal. I then fitted the other elements in.

"The two main challenges in this mix were that Nathan had overdubbed a lot of cool guitar parts, and I wanted to make sure that a high level of honesty was retained. Taylor had thrown on lots of background vocal parts [the screenshots show 31 backing vocal tracks], and it was fun for me to explore these and put each in their own sonic space and still have a degree of innocence and believability, so it didn't sound over-produced. Once again, it's all about the lead vocal communicating with people, and if it sounds too slick, the sense of honesty may be diminished.

"Fearless was a live‑band‑in‑the‑studio situation, so there was an inherent organic nature that I tried to retain in the mixes. The new record was much more ambitious in terms of arrangements and sounds, yet I still wanted to retain the sense of intimacy. Taylor's records are all about the straight communication wire she has to her audiences, and so I wanted to maintain that, while not diminishing the power of what Nathan and she had done musically, which included some very cool stuff.

"Nathan told you that many of Taylor's songs on this album had a retro quality? Yeah, that fits. Like Nathan, I prefer the warmer, more intimate records, with space in them — records that really communicate and that are not just a technical exercise. To me when we talk about a retro or vintage quality, it's not just about the sound, but also about performances from the days when things couldn't be edited or overdubbed to death. Vintage is about real music, a combination of a certain sound and the fact that people performed more, and things were mixed in a way that brought that out.

"I didn't use any outboard for this mix. It was all plug‑ins. I often use the Waves SSL plug‑ins as a basic channel strip, and I'm a big fan of the UAD stuff, so there's a fair amount of that in the mix. I also use a lot of delays and reverb plug‑ins, like the [Avid] D‑Verb, Reverb One, UAD 140 and UAD 250, and so on. Reverb can eat a lot of space in a track, but I like the sense of space and colour and emotion that it can bring. I'm not one of these people who go around saying that they hate reverb.

"I'm a big proponent of mono reverb, and particularly on Taylor's last record I used a lot of that in the middle, and then I'd open up the space around that. When I hear '50s and '60s music, there's something about the vocal occupying the centre of the mix that blows me away. So I'm trying to apply that in every mix that I do. If you listen to the songs on Speak Now, you'll hear varying degrees of mono reverb in the middle. Sometimes there'll be delays outside of that. It's all about trying to create a picture and a mood. Records and the radio used to be about people looking through a telescope, getting a narrow view into another world. Today things have become so wide. But limitations will sometimes bring out things that you can't define in other ways.”

Justin Niebank used few plug‑ins on the rhythm section at the mix, but his mainstay was Waves' SSL E‑channel (used here on the bass).

Justin Niebank used few plug‑ins on the rhythm section at the mix, but his mainstay was Waves' SSL E‑channel (used here on the bass).

Drums & bass: Waves SSL E‑channel, Avid Smack!, Bomb Factory Fairchild 670.

"I didn't use many plug‑ins on the drums in 'Mine', mostly just the Waves SSL channel strip, and EQ. I also didn't do too much to the bass, because it had been recorded through a great mic pre, the Universal Audio 2108, which is incredible. You can mess with it and it adds this wonderful killer harmonic. But of course it has been discontinued. The bass had gone through a Distressor after that, so I only added some mild compression from the Waves SSL channel.

"When working in the box, I still mirror a bit what I do on a large console. For example, I split the vocal out to another track with parallel compression. One of my favourite things in plug‑ins is if they have a mix feature, which allows me to emulate that effect a little faster. I'll also split everything into subgroups: I had a drum subgroup for crushing, which had the Digidesign Smack! plug‑in. Another drum subgroup had the Fairchild 670 plug‑in on it.”  The drums were subgrouped and fed to several different compressors, among them the Bomb Factory Fairchild 670 emulation.

The drums were subgrouped and fed to several different compressors, among them the Bomb Factory Fairchild 670 emulation.

Vocals & guitars: Waves Renaissance Vox & De‑esser, UAD 1176 & Roland 201, Sound Toys Echo Boy, Bomb Factory 1176, Pro Tools EQ III.

"One of the things I like about Pro Tools, whether I'm mixing in the box or on the board, is the ability to split vocals off over different tracks, with different treatments on each. I'll have some moderate compression on the main lead vocal track, more often than not the Renaissance Vox, and I'll follow that with the good old Waves De‑esser. This was the case on the pristine lead vocal track on 'Mine'. On subgroups, I'll often use the UAD Precision De‑esser, though not in this case. I will then split the vocal off to another track with more aggressive compression and EQ; in the case of 'Mine', it was the UAD 1176. Niebank's approach to mixing vocals involves multing the lead vocal to several tracks and applying parallel processing, here using the UAD 1176 compressor. I'll sometimes split off a third channel and have the UAD Fatso on that. On 'Mine' I used the UAD Roland 201. I also added several delays to the lead vocals, and the Sound Toys Echo Boy.

Niebank's approach to mixing vocals involves multing the lead vocal to several tracks and applying parallel processing, here using the UAD 1176 compressor. I'll sometimes split off a third channel and have the UAD Fatso on that. On 'Mine' I used the UAD Roland 201. I also added several delays to the lead vocals, and the Sound Toys Echo Boy. One of Niebank's vocal delays came from Sound Toys' Echo Boy. I'll create a balance with all these things together. I can't tell you exactly how, it's a feeling thing.

One of Niebank's vocal delays came from Sound Toys' Echo Boy. I'll create a balance with all these things together. I can't tell you exactly how, it's a feeling thing.

"The backing vocals on this song were traditional harmony vocals, and I tried to give each their own little sound. I used the Renaissance Vox on most of them, and also the UAD 1176 and the Bomb Factory 1176. Eventually they also went to a subgroup, on which I had the Waves SSL channel. In general I use a lot of EQ — I'm not afraid to use Pro Tools' regular EQ. I'm a big filter fan. That's a big key to what I do, like in the case of 'Mine' making sure there's enough space for all these vocals and guitars. I like UAD's Pultec emulation plug‑in, and recently I've also become a big fan of UAD's Trident A‑range EQ. Or I'll use the [Waves] Renaissance EQ. I'm not picky. I didn't add many effects to the guitars in 'Mine', but did use the SSL channel strip on many of the guitar tracks, plus on a couple of tracks some delay and reverb.

"The final thing to add, which is interesting, is that normally when I mix in the box I spend quite a bit of time adding plug‑ins that generate harmonic distortion and analogue‑like textures, but when I mixed 'Mine' this didn't come up. Because Nathan had recorded much of the material via the MCI tape recorder, I naturally defaulted to how I used to mix from analogue tape, which meant messing a bit with the top end, and making sure things weren't flabby. I did use Sound Toys' Decapitor plug-in on quite a few tracks on this album, though, which does add harmonic distortion. It's one of my favourite new plug‑ins.”

Final mix & mastering: API 2500, NTI Nightpro EQ3D.

"The whole session was in 24/48. As I mentioned before, I mixed to analogue, on an Ampex two‑track machine, and also had the mix on hi‑res Tascam DSD, and put the API compressor and NTI Nightpro EQ3D on the mix. The mastering engineer, Hank Williams, then made his choice between the analogue and digital versions. If a little air and compression is added during mastering, I'm cool with that. I'm not precious about my mix. I want someone else's opinion, and I feel that a strong balance will survive. The only thing I really don't like is the limiting that makes so many of today's records sound abysmal. Luckily I can get away here in Nashville with putting quite a lot of dynamics on my mixes, and they're left in mastering. The interesting thing is that it means that these records sound better on the radio. Everyone wants to compete, but all the limiting that's done makes records sound like shit on the radio. People don't want their faces ripped off by music, they want records to wrap around them. I tell people that that when a record with more dynamics comes on the radio, it'll sound better than anything else, but to convince young people of that is really tough.

"The recording industry is in crisis, and there are many reasons for that, but one of the contributing factors is technical, and the technical side of the industry needs to take responsibility for the problems we are having. We are not making things any better by crushing records to death and making them sound like sonic wad. The tendency to tune everything also doesn't help. The artistry of great singers is in how they work with pitch and timing. What creates the individual nature of an artist is how he or she approaches pitch in time. Nobody hits a note straight on. Ray Charles never sang dead in tune. It was about where he placed things in time. And we're killing that in music. I have Auto‑Tune and Melodyne, but prefer not to use it, and I didn't use any on the Taylor album. Occasionally, if I hear something that bugs me, I may brush it with a little Auto‑Tune, but more often than not I get vocals that are over‑tuned, and I'll ask for a version that's not tuned. If my gut instinct is that it affects the performance, I'll make that call. We need to get back to performances, and I wanted to be a bridge between the creator of music and the listener, and not making mixing a technical exercise.”

Justin Niebank: Mixing In & Out Of The Box

Justin Niebank has more than 400 album credits to his name, and counting. The artists he's worked with include Eric Clapton, Etta James, Keith Urban, Willie Nelson, Bon Jovi, and many, many more. Originally a Chicago native and a bass player, Niebank now divides his time between his own studio and his room at Blackbird Studios, which features an SSL 9000 K‑series desk, and ATC and Genelec 1031 monitors. To hear that Niebank mixed Taylor Swift's Speak Now 'in the box' comes a little bit as a surprise, because he has a reputation for a more traditional approach to mixing and recording. When queried, this indeed turns out to be the case, but not so much in his attitude towards gear as in an emphasis on the importance of performance.

"During the last 10 years my career has become much more about mixing. I've gotten used to certain procedures on a large desk, and I like the physicality of a large desk and the potential for mistakes and the unexpected. I've also been mixing in the box for a long time, since my programming in Cubase and Nuendo days, so it's not foreign to me either. But I have had to work out some ways to still have spontaneous things happen when working in the box. One way of doing that is never to have a template. I never template anything, whether when working in the box or with a desk.

"I start every mix for every project from scratch, based on what the song and the artist are about. I change everything about my setup before each project, because I get bored otherwise, and I want the song and artist to inspire me in what I'm doing, as opposed to fitting the song into my formula. I do my best to give every artist that I work with, and by now that's a ridiculous amount, a sound of their own. That has been the main hurdle for me in mixing in the box — the technicality of it is not a big deal. I'm pretty comfortable using the mouse and keyboard, and I only occasionally use my little Euphonix controller. But not working with a template has made it hard for me to compete against the big mixers, who all tend to use them. It works for them so I don't fault them for it, but I had to figure out a way of not doing that and still being able to compete with them.

"But for me, all this talk about digital versus analogue, and in the box or out of the box, is a bit silly, because the source is everything. What matters most are a great song and a great performance. The single most important piece of equipment in a studio is not the analogue tape recorder or the DAW, but the record button of whatever machine is up whenever the artist has a moment of inspiration. If that inspiration is caught on a decent format, it will make a great recording. That's the bottom line.

"Recording on analogue was OK, but what you put in and what came out were two different things and there was a point at which this drove me crazy. I did not like the sound of early digital, but when I ran into the earliest 16‑bit version of the [IZ] Radar it astounded me, because it sounded great, and it also had some wonderful editing features. There are times I wish I could still work with it. For a long time after that I also used Nuendo, and Cubase, but five or six years ago it became obvious that Pro Tools was the medium of choice for the majority of my clients and so I switched to that. I still use Cubase 5 for some sequencing and programming, though, because it has some wacky VST things that I love. I also use Reason in Pro Tools for programming; whatever sets me off.

"The sound of digital, including Pro Tools, has become way better, and I can get out of Pro Tools now what I want. An engineer's job is simply to record a performance, and if it's on analogue, I'll deal with it, and if it's on digital, I'll deal with it. As an engineer I have always been wary of engineers who say that they can only work in analogue or this way or that way. The only thing is that you have to adapt your EQ and miking techniques when working with digital. Many engineers used the same techniques with digital as they used with analogue, and then they were wondering why it sounded so bright. I will do whatever it takes to get my job done, and if somebody wants to do it a certain way because the budget requires it or for another reason, then I have to get my chops together to do it that way. If gear gets in the way of music, then it's off track. The most important thing is not to make the recording process more important than the music.”