With live music on hold and lockdown persisting, social media is your best bet for connecting with fans. We offer some tips for recording music videos remotely.

Although many areas of the economy are starting to open up again, music is an area that will doubtless lag behind. Live music, with its small and (hopefully) crowded venues, and band practices, with their even smaller, sealed rehearsal rooms are not likely candidates for early lifting of restrictions. Especially when you add in the amplifying factor (pun intended) of people vigorously exhaling as they sing and dance along. So what's a band to do?

At the beginning of the year my band was already considering the changing dynamic around music listening and thinking about a virtual gig (if the mountain won't come to Mohammed...). However, these plans to adapt a regular practice into a filmed, warts-and-all show were scuppered, like so many things, by the coronavirus outbreak.

But if you've got your instruments, and a handful of smartphones and microphones, surely there's something you can do? Sure enough, soon after lockdown started, a smattering of videos started appearing in everyone's social media and video feeds showing bands doing just that.

Sometimes you just have to jump on the bandwagon as it passes. But is it as easy as it looks?

Getting Started

Your first task will be to agree what song you're going to play. I don't mean to be flippant here, but the song, or more specifically the arrangement, will affect how you go about things. A key thing to understand is that, no matter how much it might seem like it, these videos are not recorded live. Which means it's much easier to manage if, as well as a click, there's one part that plays all the way through the track. You can edit out bits later if you want, but starting with everything built around a single source makes things much easier.

Once you've chosen your track, and agreed on the 'spine' of the recording, you'll be thinking about how you're going capture your performances. Modern smartphones will take excellent-quality video in any half-decent light. You can certainly aim higher and get a DSLR or video camera involved, but unless you're planning something very clever your audience probably won't notice.

If you're just recording voice and 'normal' acoustic instruments then you could well find that actually the audio quality from your smartphone will do the job as well. After all, the microphones are optimised to work on the human voice, and besides, most videos on social media aren't expected to be particularly high quality.

You don't need an expensive camera to make a decent video — any modern smartphone should be more than up to the job.

You don't need an expensive camera to make a decent video — any modern smartphone should be more than up to the job.

But if you do want to get a better recording or if you want to capture more challenging signals (hello bass and drums, I'm looking at you) then you'll need to get a bit more involved...

The Low Down

Just as low frequencies remain the bane of playback in project studios, they cause problems with recording, especially in rooms with no acoustic treatment. Long wavelengths, lots of energy, phone microphones and small rooms don't mix; it's just physics.

So you won't have much luck trying to record a decent bass guitar part with a phone, but fortunately it's an instrument that works very well plugged straight into a high-impedance instrument input on an interface. So do that. If your bass player doesn't already have access to an audio interface then beg, steal or borrow one, because any other approach is definitely going to be more complicated than that. Don't really steal one though, that's not right; especially when you can pick them up new for as little as £35$35.

Other instruments with particular low-frequency extensions can also be challenging to record in a normal domestic environment, so if you've got a low piano part or double bass then consider either using a virtual instrument, an electric keyboard or a pickup output. I'm not saying you can't record these instruments in an untreated room, but I am saying that it can take a lot of experience to get a decent sound. And you may end up having to spend longer trying to fix something in the mix when a simpler approach could have given you a better sound from the beginning.

The other instrument that's always tricky to record is, of course, drums. It's not just the low frequencies of the kick and toms, or the complex high frequencies of the cymbals, it's also the volume! But fear not, even if you don't have a convenient barn next door there are always alternative approaches.

Probably the easiest and most consistent way would be to use an electric kit. From this you could either take the line output as a stereo file, or the MIDI output to use with the drum VSTi of your choice. Not everyone has a virtual drum instrument though, and not every drummer has embraced the opportunities of an electric kit. You could look at 'quiet kit' options, with perforated drum heads and cymbals, but persuading your stickman to make such an investment might not find fertile ground.

Percussion doesn't necessarily have to mean a drum kit though. A cajon or set of congas can provide a bit of rhythmic drive, and a shaker and tambourine can fill out that high end without upsetting the neighbours. Or you can take the approach our drummer did, and pick a couple of key bits of hardware and get inventive (see 'Quiet Drums' box).

If your video shows you all playing in a series of bedrooms and living rooms but your audio sounds like it was recorded in St Paul's Cathedral, that's going to feel a bit incongruous. So instead I'd suggest a fairly dry convolution reverb... And don't dial in too much of it.

Come Together

So you've got your track agreed, you've worked out what you're all going to play, and how you're going to record it, but you're going to need a bit of co-ordination.

Our band chose an Americana-ish song, formed around the vocal and acoustic guitar lines. Those both being my jobs in the band, I kicked off the process and collated all the files coming back in for mixing. I'd definitely recommend the approach of having a single person lead on all the collation and distribution of files. Whilst you could try and use a shared project file via Dropbox or similar, to do it properly requires a degree of consistency and clarity around version control and file naming, and that's difficult to maintain. You don't want to be taking a call from an overly emotional bandmate that starts, "What do you mean the file's not there?"

In our case we shared WAV and video files, rather than any DAW project files, so we just attached them to emails and let Google Drive do its thing in the background. This worked seamlessly and we had no issues with file transfers. I'd definitely recommend keeping things as simple as possible.

If you're all comfortable playing to a click then you can record your core track(s) that form the spine of the song and then send them to everyone else simultaneously for them to record their parts. But if click tracks bring one of your bandmates out in hives (he says, casting a sideways look at the drummer) then you might be best taking a sequential approach. For example, I recorded a guide guitar and vocal track, sent it on to the drummer, and then re-recorded my parts once I'd got the rhythm parts back from him. Then it was on to the bass player and finally the lead guitarist.

Of course, it might be that not everyone in your band is comfortable with recording software, or even has any on their computer. But if there are two things that lockdown has taught us, it's the value of video conferences and screen sharing, and that there's a free tool for virtually everything, only a download away. So although our bass player had neither software nor recent DAW experience, an hour on Zoom later and she was up and running with a trial version of Reaper. Not long that after that, I had my hands on a bass track.

Assembly Line

Once you've got your files in from your band mates you can start cracking on with your mix. Some things will probably be refreshingly straightforward, for example a DI'd bass part should slot straight into any existing templates or plug‑in chains you already have. And if you're used to recording your own parts then you'll probably already have a good idea of how to handle them.

Other parts will present a different set of problems, but one common one is likely to be dealing with the sound of untreated rooms. I'd suggest two complimentary approaches here: adapt and embrace.

Under the adapt banner I'd advise that high- and low-pass filters are your friends. A purist may object, but getting heavy with your cuts here, so that you've really only got the frequency range you actually need, will be a better bet than trying to retain the fidelity of a nasty-sounding room. This is especially true of any parts that don't feature prominently in the mix, like backing vocals.

If things are getting boomy at the low end, a slow-acting compressor, which lets the initial transient of a signal through but clamps down hard on the tail, can really help tidy up drum and bass parts.

The other half of the strategy is to embrace what you have. If your video shows you all playing in a series of bedrooms and living rooms but your audio sounds like it was recorded in St Paul's Cathedral, that's going to feel a bit incongruous. So instead I'd suggest a fairly dry convolution reverb (a drum room preset is often a good starting point) that feels like it's a good, if slightly flattering, representation of what people are seeing on their screens. And don't dial in too much of it.

If you do use a heavy reverb, or any other strong spot effects, maybe take a quick screen capture video of you dialling in the controls. That can be a nice touch to drop into the footage, particularly if the plug‑in has got a nice GUI.

Sound & Vision

Since I've mentioned the video, let's dig into that a bit more. Video editors are, in many ways, similar to DAWs — they all do pretty much the same thing, they all have their advocates and detractors, and they range in price from free to more than I paid for my first car. I use Apple's Final Cut Pro X at work regularly and have used Adobe Premiere previously, but didn't have access to either of these during lockdown so I needed a simple alternative.

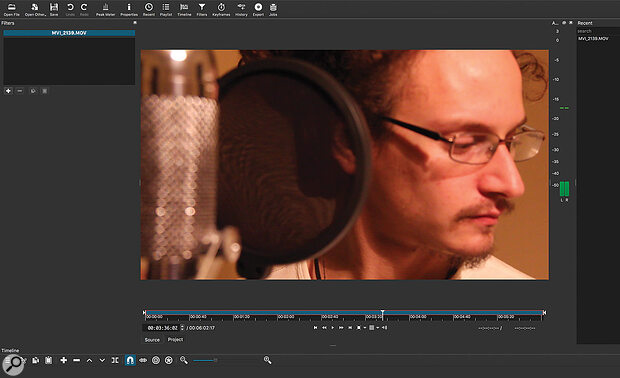

Shotcut is a free, multi-platform video editor that offers all you need to put together a music video.

Shotcut is a free, multi-platform video editor that offers all you need to put together a music video.

If you're a Mac user then I can recommend iMovie as a hugely capable but still fairly simple tool. For PC users, DaVinci's Resolve looks like a hugely powerful tool, even in its free incarnation, but it also asked far too much of my ageing computer. I ended up using Shotcut, a much less ambitious programme but still very capable (once you've got your head around the paradigm that 'everything is a filter'). Also, it's free [See https://shotcut.org].

It's worth remembering just how much heavier the processing requirements are for video editing at this point, particularly if you're planning a video that features, as most band lockdown videos do, multiple video streams running concurrently.

It's also worth thinking about this side of things when you approach panning decisions in the mixing stage. If your wailing guitar part comes in panned hard right, it's much easier for the viewer if the gurning guitarist also appears on the right-hand side of the screen. Once a particular part has settled in the mix you can relax this approach a bit, but maintaining visual and sonic consistency helps when introducing new elements.

Final Thoughts

My band, the Southern Wild, have just started recording another track, so we'll be taking a few of these pointers on board. But there are several other lessons to share, most of which will be fairly familiar to most readers from your audio recording experience.

Firstly, make sure everyone's working to the same vision. Sharing a 'rock' mix when everyone else is expecting an acoustic/folk number may not go down too well. So as well as getting some agreement up front, share your progress along the way and make sure that everyone's still happy with how things are going.

Likewise with your video. You're all probably happy on camera when you're performing, but in the gaps between your backing vocals will you be disappearing off screen? Or do you need to work on your dance moves? Again, agreeing these things in advance saves time later.

But the final and most important lesson is that this is actually all achievable. Your audience won't be expecting Abbey Road quality; so as long as everyone has some means of capturing a take, and as long as you focus on the song and the performance, you'll be forgiven all manner of imperfections.

So there you have it; get the band together (virtually) and get recording. You just need to agree on a song...

Quiet Drums

Drum kits can be a challenge to record at the best of times, especially if you're using the built-in mic on a phone. So why not use some quieter percussion instruments to add some rhythm to your music video?

Drum kits can be a challenge to record at the best of times, especially if you're using the built-in mic on a phone. So why not use some quieter percussion instruments to add some rhythm to your music video?

Recording even a stripped-down set of drums in an untreated domestic room is always going to be a challenge. Our drummer James shared this bit of wisdom:

"Trying to get a balance between the bass drum and the snare drum in a small room was tricky. I ended up putting the mic nearer to the bass drum and putting my snare drum on a cushion (so it muffled the snares), and I used a hotrod stick to bring back some of that 'snare‑y' sound. In retrospect I could have probably just used the hotrod on my leg and got the same effect."

Format Wars

Interoperability is not the challenge it once was. Agree your audio recording format up front and you'll find you can pretty much import anything into anything else. The only place you might hit a few hitches is if you've got someone using an older hardware recorder — sometimes these will only accept 16-bit WAVs rather than 24-bit ones.

The video side is very similar. Despite all the different audio and video sources, I was able to import everyone else's files straight into Cockos Reaper and Shotcut with no issues whatsoever: another useful reminder of how much simpler it's become to collaborate remotely.

Phone Smarts

Although the technology packed into your pocket isn't far from the last century's science fiction, it only takes a couple of minutes on social media to see how badly it can be abused. Fortunately there are a couple of simple things to remember to get the most out of it:

- It's all about the light. Lots of light, preferably natural light, will make life easier for your camera and your editing. But remember to make sure that light is shining onto your face not your back. Silhouettes are strictly for the witness protection programme.

- Audio levels: If you're using the audio on your phone it will most likely set the levels automatically, so once you've hit record, give it a bit of gusto to set the maximum level, pause for a moment, then start your performance.

- Landscape: Unless you're shooting for TikTok or Instagram, film in landscape. Two thick black bars down the side of the scene is just several thousand lost pixels of resolution.