With a little help from producer/engineer Tucker Martine, the Decemberists' latest album went from barn to barnstormer...

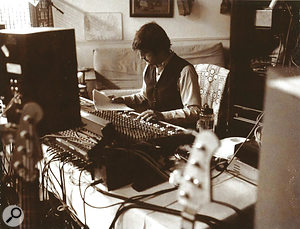

Tucker Martine at his Flora Studio in Portland, Oregon.Photo: Vivian Johnson

Tucker Martine at his Flora Studio in Portland, Oregon.Photo: Vivian Johnson

Portland, Oregon natives Tucker Martine and the Decemberists earlier this year enjoyed their first US number one with the band's sixth album, The King Is Dead, respectively 18 and 11 years into their careers. "Yes,” confirms Martine enthusiastically, "everybody was surprised! We still are! I gravitate towards things that I think are artistically rewarding and that have something to contribute to the world of music. I never think about how popular what I'm working on will be. That's just so beyond my control, it's not worth focusing on.”

The King Is Dead was a surprise in more ways than one. The Decemberists had, over the course of five albums, from Castaway And Cutouts (2002) to The Hazards Of Love (2008), carved a niche market for themselves with a kind of 'chamber pop', using instruments such as banjos, accordions, violins, xylophones, organs, and so on, often referencing '70s British progressive rock. By contrast, The King Is Dead is a relatively straightforward collection of Americana. With almost all prog references erased, it features REM guitarist Peter Buck on three tracks, and prominent Americana singer Gillian Welch on seven.

Rubber Band, Paperclip, Rock

Producer, engineer, mixer, drummer and sound sculptor Tucker Martine has been involved with the Decemberists since 2006's The Crane Wife, the band's major‑label debut for Capitol. The King Is Dead is therefore his third outing with the group. Although it's his first number one album, the 39‑year old Martine has not exactly been working in the margins during the 15 years of his studio career. As well as experimental artists such as Wayne Horvitz, Tift Merritt, Thao Nguyen, Brian Blade, Musée Mécanique and Laura Gibson, Martine is also known for his work with guitar genius Bill Frisell, singer Laura Veirs, Sufjan Stevens, My Morning Jacket and Spoon, and he has an engineering credit on REM's brand‑new album, Collapse Into Now. Martine has also released his own work, including field recordings on albums with intriguing names like Bush Taxi Mali (1998) and Broken Hearted Dragonflies: Insect Electronica From Southeast Asia (2005), and together with Robert Fripp and Steve Moore, the producer was co‑responsible for the Windows Vista start‑up sound.

Tucker Martine's distinctive musical outlook was shaped by his father Layng Martine Jr — a successful Nashville songwriter who wrote a number one hit for Elvis Presley ('Way Down' in 1976) — and by his time at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, studying with the legendary Harry Everett Smith. An eccentric mystic, film‑maker and ethnomusicologist, Smith compiled the six‑album Anthology Of American Folk Music (1952), a huge influence on the folk and blues revival of the 1950s and '60s, which encompassed people like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez and played a central part in the subsequent rise of Americana.

Martine recalls: "I didn't realise this at the time, but in hindsight I grew up around the craft of music making. I grew up in Nashville, and listening to my father writing songs and taking them from an initial rough idea to completion was a good education in production. As a young adult, I lived in Boulder for a while, and one of the classes I took at Naropa was about using the recording studio as an instrument. The teacher handed each of us a plastic bag with a rubber band, a paper clip and a rock, and our task was to make a 30‑second composition using only these things and a microphone and a tape recorder. We'd been learning how to manipulate tape to get effects, like tape loops and so on, and this tape machine composition class was pretty fascinating. Brian Eno and particularly Daniel Lanois were other major influences on me. They made me realise how environmental sounds and minimal ambient music can be relevant to a pop record, and this set me further down the road towards doing production.”

Explorations

Flora is based around an API Legacy desk, which was used to mix The King Is Dead.Photo: Vivian Johnson

Flora is based around an API Legacy desk, which was used to mix The King Is Dead.Photo: Vivian Johnson

After his experiences in Boulder, Martine travelled for a while around the US and eventually settled in Seattle in 1993, where he had found a community of like‑minded musicians. Drawn to the craft of recording, he had gradually acquired recording gear and taught himself to engineer, and he set up a recording studio near Seattle, which he called Flora. In 2006, he moved to Portland, where his studio is now located in the basement of his suburban house. He commented, "I feel at home here in the musical community in the north‑west, and I've been very fortunate that I've been able to continue to make a living working on projects that I really like. I also like the quality of life here, so for me it doesn't make sense to move to a recording Mecca like Los Angeles.

"While the music community here keeps me busy with recording music, I continue to have a real love of textures and found sounds, and a fascination with all the different ways in which sound can be manipulated. Sometimes I spend three months in a recording studio working on a record that amounts to 45 minutes of music, and I have made records of field recordings that happened in a couple of afternoons. There's no mixing required, and no driving yourself crazy over little minutiae like whether one sound can be slightly louder and a little bit more over to the left, or can be a little bit darker. I guess that my explorations into abstract sounds have helped me in being aware of how infinitely many ways there are to present a three‑minute song.

"Throughout my career I've spent a lot of time reconciling my interest in these things and my interest in the craft of songwriting and in more traditional recording. In a lot of music that I like, there is a carefully constructed quality, but also a recklessness, a kind of freedom, and I look for those things in my own recordings. That can take the shape of a rootsy Americana record, like the new Decemberists record, or even the previous Decemberists record, which was conceptual and much more kind of 'composed' and long‑form. I look for the same qualities whatever the project is. You can do things off‑the‑cuff, or belabour things greatly, construct something piece by piece and aim to create a huge, ambitious production. I'm a fan of it all and am always looking to do things I haven't done before.”

Tucker Martine's Flora studio features a high‑end analogue 32‑input API Legacy desk. He likes recording on his 16‑track MCI JH16 "as much as possible”, and prefers to mix to his Ampex ATR102 half‑inch tape recorder. Flora is also awash with all manner of classic analogue outboard, and equipped with a pair of Martine's favoured Proac Studio 100 monitors. While the producer/engineer clearly loves analogue recording, he also turns out to be very pragmatic about using digital. "If you're recording good music and you have some decent recording tools at your disposal and good instincts on how to use them, you should be able to make a really good‑sounding record. I've recorded albums to analogue that sound great and that I didn't think sounded so great, and the same with digital. When I do use Pro Tools, I tend to use it pretty much as a tape machine. I have no problem doing mutes and edits in the computer, but when it comes to mixing, I try to get all the tracks to the point where they each have their own output, and I sit at the desk as if the music is coming off tape, and do 95 percent of my EQ and effects with my analogue hardware.”

Pre‑production

The King Is Dead reflects Martine's pragmatic approach to digital and analogue. The album was recorded digitally in an ad hoc studio in a barn in rural Oregon, and mixed in the analogue domain at Flora. This approach resulted from the clear vision producer and band had about the way they wanted to approach the whole project, which began with an extensive pre‑production stage. "The band's songwriter, Colin Meloy, had sent demos to everyone involved a few months before the recordings, so we could familiarise ourselves with the songs. We then got together to work on the arrangements and how to approach these songs. The idea of the pre‑production sessions was to get the songs to the point where we could just count off and hit Record and maybe that would be the take. Whenever someone wasn't sure about something during the rehearsals and offered that maybe we should track this song in sections and figure things out during recording, we'd all stop and say: 'No, not this time. You have to figure it out right now!' That was our launching point.”

After the pre‑production sessions, the company ended up in a barn in the pleasant‑sounding Happy Valley for the recordings. Martine elaborates: "We wanted to go out to the country, set up in one room, play everything as live as possible and have a really natural‑sounding record. We were referencing things like Neil Young's Harvest and the Band's brown album [The Band, 1969]. Of course, it turns out that most of those albums were not made that way, but they give you the feeling that they were. They sound as if they could have been recorded in a barn or a place like that. Similarly, our main aim was to give a sense of place to the album, and to have the recorder going all the time. We also had this idyllic idea of regularly camping out and being outside and had envisioned recording outside and using natural sounds and so on. But in fact, we hardly did that, because it rained so much while we were there, May to early July 2010. Also, over time the record began to reveal itself to us, and we felt that to include those kinds of things would be really forcing it. The only thing that survived was a snippet at the end of 'This Is Why We Fight', of Sherry Pendarvis, the woman who owns the farm where we were, singing with the rain in the background. It seemed appropriate for the rain to make an appearance somewhere.

"We started by recording everyone together in the barn, and our plan was to then make adjustments as we needed. Some songs, like 'All Arise!' were recorded live in that way, apart from Gillian's vocal overdub — I later went to Los Angeles to record her. But in many other cases we did end up recording the songs more piece‑by‑piece. We kept the live‑in‑the‑studio approach as our default mode, but then often replaced much of what we had. On all songs except for 'This is Why We Fight' and 'Down By the Water', we kept several parts of the original takes. They would often be Nate [Query]'s bass parts — he's a great bass player who tends to play keeper takes right away — and the drums. It depended on the song.”

Barn In The USA

As a medium for tracking in the Happy Valley barn, Martine explained that he "borrowed a [iZ] Radar system to record on, because it is really portable and it sounds good. We discussed recording to analogue tape, but we didn't want to use my 16‑track, because we'd run out of tracks, and there was no other tape machine in town that we could have for that long and that we felt was reliable enough. We didn't want to be out in the country and it to take a day for a tech to get out there, and for us to be shut down for any length of time because of tape‑machine problems. That did not seem worth it. I have some friends who use the Radar, and they regularly rave about it, and I know Lanois uses it, and I am friends with Adam Samuels who has been working a lot as Lanois' engineer, and he also swears by it. So I was excited about the possibility of finally being able to find out what it is like to work with the system. It meant that I had a little bit of a learning curve with it, but it's straightforward once you get going.

"My experience of the Radar is that it really is like working with a tape recorder, with a few extra benefits, which are so minor that once you're used to Pro Tools, it's hard to not get impatient with the system. The editing functions are very archaic, it is very much like cutting tape. You really have to want to do an edit, because, like with tape, it's a matter of telling everyone to go out and take a break, because it takes some time. But I liked that about it. It fit the modus operandi of the record we were working on, which was all about committing and playing together in the same room and not having a separate control room, so I couldn't really judge what was going down. For us the atmosphere and the idea of people playing in a room was more important than having flexibility and total control. There were times when we wished we had the comforts of the modern studio, but it was great that editing was so difficult, because it meant that we had to keep our focus on the performances and getting them right. I recorded to 48/24, and the Radar did sound good. Tucker Martine took his favoured Proac monitors to the Happy Valley barn where the album was recorded. The Mackie desk was used only for monitoring.

Tucker Martine took his favoured Proac monitors to the Happy Valley barn where the album was recorded. The Mackie desk was used only for monitoring.

"I also bought a little Mackie console off Craigslist, just because we needed something to monitor on. All my efforts to get something better‑sounding fell through. It just did not make any sense to rent a large board, because it would have cost more money than we could justify, given that it was only to listen back. I brought the rest of the gear from Flora, including my own microphones, mic pres and other outboard gear, and my Proac Studio 100's. I brought 25 mic preamps or so and all of them are about getting slightly different colours. But I have to say that I am not very particular about what mic pres I used. I don't go nuts. I am more interested in being ready to capture the idea as soon as it is happening, and not making the musicians wait around while I compare different mic pres. I like to try new things, and I don't get too set in my ways. I do have a few combinations that I love. Lately my favourite has been the Telefunken V72, and for the overdubs on the Decemberists record I tried to use those as much as I could. I just love the sound of them and they flatter anything unpleasant that digital may try to impart. I also had Neve 1073s, which I like a lot. You can't really go wrong with them.

A Faraway Perspective

"Of course, the barn was definitely not a controlled recording environment, and when you get to a recording space like that, there's no way around using your best instincts where to put everybody and what microphones to put up and where, and then listening to the sounds and tweaking from there. The mic setups varied from track to track, in part because all the band members play various different instruments, in part because there would be different challenges for different songs. There were some constants on the whole record, like the reissue Neumann U47 as a mono overhead on the drums, an AKG D12 on the bass drum, KM84 on the snare top, and U87 on the toms, which rarely got used. I wanted enough close mics to keep bleed under control, but I also really wanted to make sure that you could hear the sound of the barn, so we didn't go to all this trouble to set up a studio in the country and then you don't hear it. I hung a Beyer M160 ribbon mic from the rafters for a faraway perspective on the drums — I only ended up using that occasionally — and when it wasn't being played I also used the piano mics, which were B&K 4011s, as ambience mics. A big part of the balancing act for this record was to handle the ambience. Of course, when everyone plays together and you know there's a good chance you're not going to use everything, you can't use ambient mics, and you also have to be very careful about spill from louder instruments like the electric guitar on other close mics.

"We recorded Colin's acoustic guitar, as well as his vocals and his harmonica, with the Wunder CM7. In the cases where he sang live with the band and hence played guitar and sang at the same time, I had a Shure SM7 on his vocals, because it has less bleed. Scenes from a barn: Decemberists frontman Colin Meloy lays down a vocal and acoustic guitar take, with a Shure SM7 for the former and a Wunder CM7 for the guitar. Photo: Autumn De Wilde There are a couple of songs on which we kept his initial live guitar/vocals takes, like 'All Arise!' and 'January Hymn'; on the rest he overdubbed his acoustic and vocals separately. Other microphones were a Coles 4038 on the accordion, a Neumann KM86 on the banjo, the pedal steel had a Royer 212, Chris Funk's guitar amp had a Royer 121, on Peter Buck's guitar amp I had a 121 and a Sennheiser 409, and the bass was recorded purely using the Evil Twin DI. I did reamp the bass a few times with Nate's Aguilar amp. I don't recall all the mic pres that I used, but Colin's vocal chain was CM7 going into a Neve 1073, I used the Telefunken V72 on the guitars, and the API 560 graphic EQ on the bass drum.

Scenes from a barn: Decemberists frontman Colin Meloy lays down a vocal and acoustic guitar take, with a Shure SM7 for the former and a Wunder CM7 for the guitar. Photo: Autumn De Wilde There are a couple of songs on which we kept his initial live guitar/vocals takes, like 'All Arise!' and 'January Hymn'; on the rest he overdubbed his acoustic and vocals separately. Other microphones were a Coles 4038 on the accordion, a Neumann KM86 on the banjo, the pedal steel had a Royer 212, Chris Funk's guitar amp had a Royer 121, on Peter Buck's guitar amp I had a 121 and a Sennheiser 409, and the bass was recorded purely using the Evil Twin DI. I did reamp the bass a few times with Nate's Aguilar amp. I don't recall all the mic pres that I used, but Colin's vocal chain was CM7 going into a Neve 1073, I used the Telefunken V72 on the guitars, and the API 560 graphic EQ on the bass drum.

"Gillian [Welch] likes to be recorded with either an SM57 or a Neumann M49, so either an $80 or a $12,000 mic! When I recorded her at Sound Factory in LA, I used both, and both sounded great.”

'Down By The Water'

Written by Colin MeloyProduced by Tucker Martine and The Decemberists

Written by Colin MeloyProduced by Tucker Martine and The Decemberists

"'Down By The Water' was an unusual case, because it's the only song from the sessions that we re‑tracked. We'd spent quite a bit of time on the original version, because we found it difficult to get it right, but at some point we decided that the version we had felt sluggish and not very exciting. We couldn't really put our finger on why, and we also felt that we were running out of time. We certainly didn't want to re-open the can of worms that that track had become. It would have been bad for morale to restart again. So we said, 'Let's give it two hours, and if it doesn't happen in that time, we'll scrap the song.' We went for a very visceral approach, with everyone playing live, and didn't talk much about what to do differently. Just count off and play! It turned out to be very exciting. Some of the excitement was due to the fact that the song was fresh, because the band hadn't played it for a while, and some of it was due to there being some frustration in the room, because not everyone was very happy about recording a song again that we'd already battled with. So there was some extra energy in the takes that contributed to it working. Peter Buck added his overdubs later on, as he did for the other songs he played on, because we only had him for one day, and we wanted to make sure that we were ready for him and could get the most out of our time with him. We didn't want to have variables like the band not getting a song right on that particular day.

"After we finished recording at the barn, I returned to Flora and loaded everything into Pro Tools, at the same 48/24 resolution. It's easier to manoeuvre things around in Pro Tools, quicker to go to different sections in each song and mute and unmute regions and so on. Pro Tools is very familiar to me, and I can do these things without having to think about it. I mixed a couple of songs directly from the Radar, but these were 'B' sides that didn't make the album. Once I had loaded all the sessions into Pro Tools, it really was like mixing off a tape machine, although I did occasionally go into Pro Tools to adjust some very detailed issues. Because I didn't use the automation on my desk, if I wanted to ride the volume for just a couple of words here and there, I'd do it in the Pro Tools automation. I also had a problem with hi‑hat bleed on the snare mic in 'Down By The Water', and solved that with a few plug‑ins. I had tried to use the automation on my console when I started mixing this album, but I felt like I was spending more energy thinking about the automation and correcting automated moves than thinking about the music, so I stopped. I really like to keep things instinctive, and if I have to think too much about the interface I lose the flow, and I no longer feel inspired.

This is just a part of Flora's healthy collection of outboard equipment. Photo: Vivian Johnson"In terms of mixing the songs for The King Is Dead, I pushed up most of the tracks for each of the songs spretty quickly, because the mixes really were about how everything relates, rather than about individual parts sounding great. It's not the kind of project where you go: 'Oh, those drums sound incredible.' In all cases I wanted to make the entire song exciting, and all individual sounds are there to make a contribution to that. I mixed 'Down By The Water' especially quickly. Sometimes you feel that you can go in several different directions with a song, and you want to explore them all before committing to one particular direction. But with this song there was just one direction, and we'd always been heading there. When I started mixing the song I knew exactly what to do. I knew what was going to be in the track, and it really was just a matter of mixing from the gut. I remember that it already sounded really good after a couple of hours. I emailed that initial mix to Colin, and he had a couple of small comments about a few words that he wanted to hear better. I made those changes in Pro Tools, and that was it.

This is just a part of Flora's healthy collection of outboard equipment. Photo: Vivian Johnson"In terms of mixing the songs for The King Is Dead, I pushed up most of the tracks for each of the songs spretty quickly, because the mixes really were about how everything relates, rather than about individual parts sounding great. It's not the kind of project where you go: 'Oh, those drums sound incredible.' In all cases I wanted to make the entire song exciting, and all individual sounds are there to make a contribution to that. I mixed 'Down By The Water' especially quickly. Sometimes you feel that you can go in several different directions with a song, and you want to explore them all before committing to one particular direction. But with this song there was just one direction, and we'd always been heading there. When I started mixing the song I knew exactly what to do. I knew what was going to be in the track, and it really was just a matter of mixing from the gut. I remember that it already sounded really good after a couple of hours. I emailed that initial mix to Colin, and he had a couple of small comments about a few words that he wanted to hear better. I made those changes in Pro Tools, and that was it.

"Another thing that sped up my mix of 'Down By The Water' was that this was one of the later songs I mixed for the project, and by this time I had the drums set up pretty much the same for every song. I might add a microphone or take one out, but apart from some small tweaks, the treatments were pretty much the same for each song. I started the mix by bringing up the drums and bass, and didn't really mess too much with them, just made sure the EQs and compression were right. I have the drums on the left of my desk, but the drum bus on the right, so I can easily ride the overall drum level, particularly as I'm not using automation. After that, I quickly brought in the other instruments, trying to keep things instinctual. There aren't too many tracks, about 26, so it was quite an old‑fashioned session in that sense. I start to get dizzy when I have more than 40 tracks! I like each track to have a purpose, and I like to know that there's space for each in the mix. Although there weren't that many tracks in 'Down By The Water', it's a pretty dense arrangement because everyone is playing for most of the song. It was tricky to make everything fit, particularly Peter Buck's 12‑string guitar. For the most part that was a matter of EQ and panning.”

Although Tucker Martine mixed to analogue half-inch as well as to digital, it was the digital masters that sounded better and were used for the album.

Although Tucker Martine mixed to analogue half-inch as well as to digital, it was the digital masters that sounded better and were used for the album.

Drums: desk EQ, Dbx 120, Chandler TG1, Drawmer DS201, McDSP MC2000.

"Most of what I did on the drums was pretty subtle. I EQ'ed on the desk, and to get the kick to come through, I would have added a little bit around 4kHz and maybe carved out around 400Hz. I used the Dbx 120 sub-harmonic generator on the kick, just to add some sub-harmonics, so you feel the bass drum more. Sometimes turning up the EQ around 60Hz just makes the kick drum sound muddy. I had my Chandler TG1 compressor on the drum bus as parallel compression, so I could add some of that in to give more attitude to the drums. As I mentioned before, there were plug‑ins on the snare to minimise hi‑hat bleed on the snare microphone. I wanted to get the snare to pop and sound exciting and be quite far forward, and the bleed was unpleasant. This may have had to do with the band re‑tracking the song and there being some frustration in the room, so everyone played harder than they usually do. So I put a low‑pass filter at 12kHz on the snare, because there was nothing valuable in the snare above that frequency, just the sizzly hi‑hat stuff. I then put a gentle Drawmer gate on the snare, which brought the sound down with 3dB every time the snare wasn't hitting, and also added the McDSP MC2000 multi‑band compressor, of which I'd downloaded a demo version.”

Guitars: API EQ, Manley Massive Passive, Lexicon PCM70.

"The acoustic guitar was doubled, and I then panned them left and right. I used a high‑pass filter set around 100Hz on the acoustic to get out some of the boom, because it's a really busy strumming pattern. I also added some air at the top end, around 7‑10k with my API EQ. The CM7 is a nice detailed mic, but it sounds a little dark. I was also making space for Peter Buck's 12‑string, and the banjo and baritone guitar. I brightened the 12‑string up a bit, boosting around 3k with a Massive Passive EQ, and I added some reverb from the Lexicon PCM70, which helped give it a little bit of its own space. Peter also played the baritone guitar, which I also sent to the Lexicon, and panned centre — I had used up all the places on the perimeter! The baritone part was really distinct from the 12‑string, and it worked fine for them to share the same reverb. The banjo, which was played by Chris, was mixed fairly low, because it was playing the same arpeggiated part as the 12‑string, and I felt that the latter would carry the song more. We did not use the pedal steel, and I don't think I did anything to the accordion.”

Bass: Urei 1176, Retro InstrumentsSta Level.

"I had the Retro Instruments Sta Level compressor on the bass. It's really transparent‑sounding and it helps to hold the bass in place in the mix without audible pumping or other artifacts. Nate has great tone and is easy to record, so I didn't need to do much on the bass. I had already had an 1176 on the bass on the way in, so there were two stages of compression, but neither were very extreme.”

Vocals: Ecoplate III, Electro‑Harmonix Memory Man, Urei 1176, Pultec EQ.

"I had set up an Ecoplate III [vintage plate] reverb, which I used on all the vocals on this record, if I did use reverb — on some songs I didn't. I'd also set up a quick delay in a Electro‑Harmonix Memory Man, and on this track I fed that to the Ecoplate on a short setting. I did not use much of it — Colin's voice is not wet‑sounding — but it just takes the edge off. Compression would have been done with my silverface Urei 1176, which I love, and EQ was most likely just adding a touch of 12k with a Pultec to open the sound up at the top. Gillian's voice would also have had a little bit of the Ecoplate reverb. I also would add body to her vocal, because it sounded rather thin. I recall adding quite a bit around 100Hz. The harmonica also had some of that plate reverb.

Final Mix

"I mixed back into the session and to half‑inch tape, but the master came from the digital files. For some reason the tape felt a little bit too dull and was less dimensional. It was strange, because with other projects the tape machine is always hands‑down better‑sounding. Perhaps it had to do with the half‑inch machine at the mastering lab. We'll never know, I suppose. It appears that the record company later remastered the album to get more loudness. My approach is not to get worked up about things I have no control over! I just show up and do the best I can with the things I do have control over. And just as it was a surprise when the record went to number one, I never thought of 'Down By The Water' as a single while we were working on it. Only after I finished the mix did I realise that it was a really catchy song that could be a strong single.”