'Papa's Got A Brand New Bag' was James Brown's statement of intent as he abandoned soulful ballads in favour of a raw and frenetic new sound.

"Most of the time, working with James Brown, it would be down to the first complete cut,” recording engineer Ron Lenhoff told me when I interviewed him in 1988. "He'd say to me, 'Ron, are you ready?' and if I said, 'Yes,' he would cut it. After that, if he got all the way through it without stopping, I'd better have it on tape. I never ran into the situation where I didn't have it on tape, but I sure as hell always worried about it.”

James Brown on stage in 1964.Photo: GettyLenhoff captured many of Brown's most iconic performances during the halcyon years when he was signed to the independent King Records label in Cincinnati, Ohio. This was founded in 1943 by one Syd Nathan, who, after initially owning a record store there, launched King as a country‑oriented label and, in 1944, based it within an old chemical plant in Cincinnati's Evanston neighbourhood.

James Brown on stage in 1964.Photo: GettyLenhoff captured many of Brown's most iconic performances during the halcyon years when he was signed to the independent King Records label in Cincinnati, Ohio. This was founded in 1943 by one Syd Nathan, who, after initially owning a record store there, launched King as a country‑oriented label and, in 1944, based it within an old chemical plant in Cincinnati's Evanston neighbourhood.

This facility was subsequently converted into a pressing plant and business offices while the adjacent icehouse was transformed into a recording studio. In 1945, the Queen Records subsidiary was formed to release the work of black artists, before being folded two years later so that musicians of all creeds, colours and musical genres could be incorporated under the King banner. This was in line with the company's non‑discriminatory policy of employing black and white workers at a facility that took care of recording, mastering, electroplating, printing, pressing, artwork and shipping under one roof. Indeed, Nathan ensured that, in addition to performing their own music, black artists such as Wynonie Harris delved into country while hillbilly acts such as Moon Mullican and the Delmore Brothers recorded R&B. This was several years before Sam Phillips did the same on his legendary Sun label with the likes of Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis. What's more, King only recorded and released songs that they owned.

In 1950, Syd Nathan launched another subsidiary, Federal Records, and this was the label that, run by R&B record producer Ralph Bass, signed James Brown and his backing group the Famous Flames. As it happens, Nathan originally passed on Brown after hearing his demo of 'Please, Please, Please', rejecting it as "a piece of trash [with] only one word in it”. Bass, however, thought otherwise, taking Brown and his colleagues into the studio so that he could produce the record that went on to become a million-seller. Several subsequent releases flopped, before the ballad 'Try Me', released in October 1958, became the first of 17 Brown recordings to top the R&B chart.

This, in turn, led to Syd Nathan reappraising James Brown's talents and, in 1960, shifting him from Federal to King. Brown had several more hit singles before, against his supposedly better judgement, the company boss was persuaded by the fast‑rising 'Mr Dynamite' to release a half‑hour concert album featuring some of his then‑best‑known numbers. Live At The Apollo, which Brown himself paid to record at Harlem's world‑renowned venue on the 24th October 1962, peaked at number two on Billboard's Top LPs chart before eventually shifting more than a million copies. Repeating the formula, a November '63 concert at Baltimore's Royal Theatre was then released the following year as Pure Dynamite! Live At The Royal. However, while this also made the Billboard Top Ten, it differed in that the 'live' tag wasn't completely authentic.

"We dropped in a studio recording called 'Oh Baby Don't You Weep' and overdubbed the crowd from a game at the ball-park,” admitted Ron Lenhoff with regard to the song that was based on a negro spiritual predating the American Civil War. "Inserting something with different acoustics was difficult, but it can be done, it has been done and I've done it.”

(Not So) Live Recording

Born in Elsmere, Kentucky, and raised in nearby Newport, Lenhoff went into the US Navy following his 1949 high school graduation, serving as a radio and electronics expert aboard a Lockheed PV2 bomber aircraft. Thereafter, he worked as a technician for background‑music distributor, Muzak, before gaining employment as a sound engineer at the Fidelity studio that he subsequently owned and operated for eight years.

In 1964, Lenhoff joined King Records as the studio's Chief Engineer and the pressing plant's Quality Control Engineer. By then, the studio had graduated from using an Ampex two‑track tape machine to a three‑track alongside its custom‑made console, while the live area was equipped with Neumann microphones and a Hammond B3 organ. The heavy metal door to the studio sometimes caused problems, audibly slamming shut during certain recordings. Up on the top floor of the late‑19th-century building was a 4 x 8-foot echo chamber, which, for no apparent reason, was equipped with an ultraviolet light. Still, everyone who worked there loved the sound, including Ron Lenhoff who continued to explain how he matched the acoustics of the 'Oh Baby Don't You Weep' studio recording with those of the Pure Dynamite live tracks.

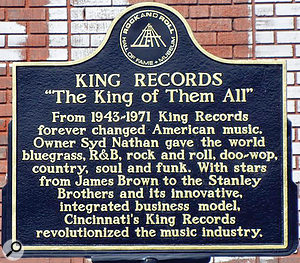

A commemorative plaque that now stands in front of the building that once housed the King Records HQ (including the studio) in Cincinnati."I would try to copy them not by dubbing anything, but simply by EQ'ing,” he recalled. "When I got to the point where I could punch up the live tape and punch up the studio tape, and run them at the same time sounding close, I would then put it all on another tape and work on it from there. Sometimes it meant going three, four or five generations before I got what I wanted, but there again, in those days, you'd really want to dirty up a studio recording for a live album. It wasn't like today when the equipment on the road enables a live recording to sound almost as clean as a studio recording.

A commemorative plaque that now stands in front of the building that once housed the King Records HQ (including the studio) in Cincinnati."I would try to copy them not by dubbing anything, but simply by EQ'ing,” he recalled. "When I got to the point where I could punch up the live tape and punch up the studio tape, and run them at the same time sounding close, I would then put it all on another tape and work on it from there. Sometimes it meant going three, four or five generations before I got what I wanted, but there again, in those days, you'd really want to dirty up a studio recording for a live album. It wasn't like today when the equipment on the road enables a live recording to sound almost as clean as a studio recording.

"While I recorded Melvin Parker's drums with a tube [Neumann] U47 overhead and a kick mic, I also tracked James's vocals with a 47. The only time he ever did anything other than hand‑hold the microphone was when he did overdubs. When he hand‑held the microphone it was like he was on stage. It wasn't a studio performance; it was a stage performance. He had a great mic technique right from the very first time I met him, so we really didn't get the problem of his voice phasing in and out. We didn't always get everything the first take, but the first complete take that he was satisfied with. If he was happy with it, we'd have it on tape. I knew I had to work that way.

"We did add echo, but that was usually done on the session, and at that time it was 100 percent live echo. We'd use anything to give him an edge, and later on we did use echo plates. Both James and I preferred to always aim for as clean a sound as possible, with plenty of separation on the instruments. I'd play with a lot of stuff, and if I thought it was going to be too far out for him, I would let him listen to it before putting it on tape. More often than not his stuff was cut pretty straight, and very seldom would I go back to do anything to it later. One of the very few things I edited for him, and it became a pretty good‑sized record, was 'Oh Baby Don't You Weep'. That recording ran for 12 to 14 minutes. King Records' A&R guy, Gene Redd, was a very fine musician, and we sat down and, between the two of us, edited it down to a little less than three minutes per side.”

This was for what turned out to be James Brown's first two‑part single, as well as the last original chart song to feature the vocal contributions of the Famous Flames: Bobby Byrd, Bobby Bennett and 'Baby Lloyd' Stallworth, repeating the gospel‑like title refrain. (The only subsequent Famous Flames chart appearances would be via old performances: a 1964 re‑release of 'Please, Please, Please' and, two years later, a B‑side issue of 'I'll Go Crazy' from Live At The Apollo.)

A Brand New Bag

A number-23 hit on the Billboard Hot 100, 'Oh Baby Don't You Weep' was also the catalyst for a complete falling‑out between Syd Nathan and 'Soul Brother Number One'. This had been building for quite some time due to, not only, artistic differences of opinion, but also Brown's frustration with King's outdated record distribution system. Matters came to a head when, during the recording session, A&R executive Gene Redd criticised Brown's piano playing. Brown promptly formed the pointedly named Fair Deal production company with Ben Bart and inked a deal with Mercury imprint, Smash Records, to release his future recordings.

Nathan responded by issuing some of Brown's outtakes and even the aforementioned 'Please, Please, Please' with overdubbed applause, before then obtaining an injunction that would prevent his wayward artist from issuing vocal recordings on any label other than King. The dispute wasn't settled until mid‑1965, at which point, armed with a new, more lucrative contract and greater artistic control, Brown made his King Records comeback with the funk classic, 'Papa's Got A Brand New Bag'.

Yet another two‑part single that this time became his first top-10 pop hit, the brand-new bag of the title signalled a change in musical direction from melodic soul‑laced ballads and gospel‑based R&B to the raw, edgy, revved‑up rhythms of Brown's increasingly attention‑grabbing live performances. These saw his dramatic stage moves now not only shape his more straightforward, hard‑hitting vocal style, but also serve as the cue for complementary instrumental breaks. Tracked that February at the Arthur Smith Studio in Charlotte, North Carolina, 'Papa's Got A Brand New Bag' climbed to number eight on the Billboard Hot 100 following its June '65 release and later won the Grammy Award for 'Best Rhythm & Blues Recording'. But not before Ron Lenhoff had to make some changes for it to become chart‑worthy.

In its original form — as finally released in 1991 on the retrospective four‑CD Star Time box set — the track lasted just under seven minutes. Following Lenhoff's remix, the A‑side/Part 1 clocked in at 1:55 and the B‑side/Part 2 at 2:12.

"That mono recording was terrible,” he remarked. "It was so muddy, you could hardly hear all the instruments. It took me two days of copying, recopying, increasing the tempo, raising the pitch, editing, EQ'ing and editing again just to brighten it up. Still, the music was really good, even without the sax solos that I cut, and after that James and I got to work together a lot.”

Recording Ad Hoc

Without a doubt, during the course of their ensuing in‑studio partnership the prodigiously talented artist from Augusta, Georgia, appreciated how his engineer paid meticulous attention to detail. This included mic placement, instrument amplification and the positioning of musicians in what came to be known as the James Brown Orchestra. At the same time, Ron Lenhoff was also flexible enough to accommodate James Brown's improvisational work methods; especially when, after a run of US chart successes he began searching for more hits.

"Whenever he was doing a concert in or near Cincinnati, James would come by King late at night and record maybe three or four tracks in just as many hours,” Lenhoff recalled. "Don't forget, at King we had the facility to record, mix, master, press and label the discs, so the finished product could be ready for shipping within 24 hours. James was well known for turning up at recording sessions without having written any songs. He'd just have the idea in his head and, when he came in, he would improvise right then and there. He could also play the drums and the keyboard instruments, so he understood exactly what he wanted. He'd build a pattern with the musicians around the bass and drums, and then bring the guitar in. All the musicians had worked with James for a long time, so they knew what he wanted and, once he got the rhythm section going, he would start working on the horns.

"All the time he was doing this, I was setting up sound levels, EQ'ing, that sort of thing. It usually took him anywhere between a half hour and two hours to get everything together, depending on whether the musicians saw right away what he was after or whether he had to pull a few teeth, which he had to do on occasion.

James Brown performs with Johnny Terry, Bobby Byrd and Bobby Bennett of the Famous Flames at the Apollo Theatre in New York.Photo: Getty"Working with all the people I did, even at other studios, I never ever saw anybody work in a session like James. He knew what he was going for and he wouldn't accept anything but that. When he left the studio he was happy. I never had him come back after a session and say that he didn't like it. You see, James wasn't a hard taskmaster during the session as long as you gave him what he wanted, which is the same as almost everyone else I know. The only guy I ever met who wasn't like that was Louis Armstrong — if anyone made a mistake, he would just say, 'Oh well, don't worry about it. We can do it again.' But I can't say there was ever any time I didn't enjoy working with James. He and I seemed to know what each other wanted, and I guess that's why we worked so well together.”

James Brown performs with Johnny Terry, Bobby Byrd and Bobby Bennett of the Famous Flames at the Apollo Theatre in New York.Photo: Getty"Working with all the people I did, even at other studios, I never ever saw anybody work in a session like James. He knew what he was going for and he wouldn't accept anything but that. When he left the studio he was happy. I never had him come back after a session and say that he didn't like it. You see, James wasn't a hard taskmaster during the session as long as you gave him what he wanted, which is the same as almost everyone else I know. The only guy I ever met who wasn't like that was Louis Armstrong — if anyone made a mistake, he would just say, 'Oh well, don't worry about it. We can do it again.' But I can't say there was ever any time I didn't enjoy working with James. He and I seemed to know what each other wanted, and I guess that's why we worked so well together.”

After King

Syd Nathan passed away at the age of 64 in 1968. A short time later, King Records was sold to Starday Records in Nashville and relaunched as Starday‑King. Then, in 1970, Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller purchased the label before selling it to Lin Broadcasting, and the following year James Brown's recording contract and back catalogue were both purchased by Polydor Records.

After Ron Lenhoff passed away at age 75 on 25th November 2006, Bootsy Collins told the Cincinnati Post how the engineer's amenable attitude had worked to everyone's advantage in the studio.

"He was always on time, and wanted you to be, too,” recalled Collins, who at 18 became the bassist for the JBs in 1970. "He wanted everything perfect. James really liked that in him, but then sometimes James did not want things so perfect and Ron knew when to compromise to make the Godfather feel in control. Musicians can be strange cats... [Ron] knew his equipment and what it was capable of doing, and sometimes he would push it to the limits. That's what I really liked about him. He was not scared of blowing things up, like a speaker or two, to make you happy or feel good about what we were doing.”

A Nice Little Earner

After the King Records studio closed its doors in 1971, Ron Lenhoff declined job offers from facilities in other cities so that he could remain close to his family in Erlanger, Kentucky. Instead, he took an engineering job of an altogether different kind, for a local company called Dover Elevator and, despite accepting gigs as James Brown's sound man on two concert tours of Africa and one in Europe during the 1970s, he was still working at Dover Elevator when I interviewed him in 1988.

"Has 'Sex Machine' enjoyed a revival on the jukeboxes and the radio?” this genial man asked me during one of my visits to his home. This was in reference to the 1970 funk smash that James Brown had co‑written and recorded with Bobby Byrd and his new band the JBs after his previous group had walked out on him over a pay dispute. "I've just received a really nice royalty cheque!”

"You receive residuals?” I asked without answering Lenhoff's question.

"Sure,” he explained. "One night in 1970, after James had done a show in Nashville, he called and asked me to do a session for him there. Well, there were no flights available, so I jumped in the car and drove all the way. It took me five hours to get there and, as soon as I arrived at the [Starday‑King] studio, James and the musicians were ready to record. So, we cut four tracks, and then, before I left, James told his manager, Bud Hobgood, 'Give Ron 10 percent of that last song.' The song was 'Sex Machine', so we wrote up the songwriters' contract and I've been collecting on it ever since...”