Blighted by drug abuse and mental illness, Heavy Zebra never fulfilled their early promise. Nevertheless, the deranged majesty of their 1972 single 'Karla' makes it a bona fide classic track.

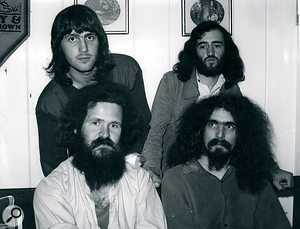

Heavy Zebra in 1971. Clockwise from top left: Stuart Nash, Nigel Spencer, Graham King and John Collins.

Heavy Zebra in 1971. Clockwise from top left: Stuart Nash, Nigel Spencer, Graham King and John Collins.

Obscure but influential — that is the legacy of Heavy Zebra, the experimental blues‑rock band that countered scintillation with self‑destruction. Their 1972 album Tipping The Scales has had a major impact on an eclectic array of artists, ranging from Massive Attack, the Orb and Nirvana to Kate Bush, the Feeling and Jay‑Z.

"That band was way ahead of its time,” Bush has been overheard saying. "Its music was just so out there, so unique, and I also had a huge crush on [singer/guitarist] Stuart Nash... It was because of him that I wrote 'The Man With The Child In His Eyes'.”

That's quite an accolade for a troubled soul who always sought musical integrity and female company in equal measure. Still, for all of the peer plaudits, Tipping The Scales garnered mixed reviews and disappointing sales at the time of its release, and it has never even been properly distributed on CD. So why, despite the lack of mainstream recognition, does it enjoy a cult status among the rock cognoscenti nearly 40 years after it first saw the light of day? And what is it about the album's standout track, the sonically bizarre power‑ballad 'Karla', that continues to inspire and entertain Zebra devotees around the world more than three decades since the group's somewhat squalid demise?

Earning Their Stripes

Stuart Nash with his trademark Gibson SG, Thwing Abbey, Summer 1971.

Stuart Nash with his trademark Gibson SG, Thwing Abbey, Summer 1971.

"The key to Tipping The Scales is the rhythm section and Graham King's lead guitar,” asserts former engineer Kevin Byrne, who tracked the sessions in a mobile truck parked in the stately home surroundings of Gloucestershire's Thwing Abbey. "It's there all the time, underpinning whatever weirdness is going on around it. By that time, the Zebra were extremely together as a band — at least in a musical sense — and when push came to shove they could really swing. That's what saved it from just being a formless mess. Of course, in many ways it is a mess, but it does have form.”

An electronics expert who spent fewer years in the music business than with the Ministry Of Defence, Byrne first encountered the nucleus of Heavy Zebra in the early '60s, when attending North London's Finchley Catholic Grammar School with Stuart Nash and bass player/keyboardist Nigel Spencer. Both of a musical and artistic bent, Nash and Spencer became inseparable friends, and in 1964 they formed their first band, the What?. A primitive blues outfit that never gigged, the What? nevertheless enabled the pair to hone their skills by way of non‑stop rehearsals.

Moving on to art college in 1967, the 18‑year‑olds struck up a friendship with one of their teachers, the maverick John Collins, who in addition to his penchant for painting strictly in monochrome, also happened to be an enthusiastic drummer. Accordingly, once they had joined forces to form an experimental art‑rock trio, it was Collins who suggested they call themselves 'Zebra' in deference to an animal that he perceived as "a yin‑yang horse, man”. And it was also Collins who, when he and his bandmates were involved in a back-alley fracas with a rival combo named the Peace Corps, persuaded that outfit's frontman, Graham King, to switch sides in mid punch‑up and become the Zebras' lead guitarist.

This addition, in conjunction with Nash sustaining a hand injury and severe concussion that forced him to strip down his previously florid style in favour of a simpler, harder‑edged technique, resulted in a heavier, more rock‑oriented sound and a change of name. "Heavy Zebra,” Nash muttered to Spencer, King and Collins during a booze‑fuelled routining session for the band's first album. "That's who we are. We're all heavy zebras.” The others agreed. A legend was born.

Taking The Reins

In 1969, in the wake of the A&R frenzy created by the burgeoning popularity of rock‑blues outfits such as Cream, the labels were ransacking every grungy dive in the capital in search of potential signings. Heavy Zebra was among them, and a chance sighting by Liberty Records' Harvey Sparks resulted in a three‑album deal.

Excited to be in a real studio, the Zebras could hardly wait to experiment even more with their sound, yet within a week they were out on their ears. This, after all, was the standard period of time allotted for an album during the late‑'60s and early‑'70s, and even though Stuart, Nigel, Graham and John were incensed to be left with what they regarded merely as backing tracks, these did make for a commendable blues‑based debut LP, Heavy Zebra II, as well as a standout song in the form of the side‑one opener, 'Theme From Heavy Zebra'. The only problem: minimal interest from press and public alike.

For the follow‑up, Nash not only came up with most of the material, but also songs that signalled a distinct shift in his mindset, featuring lyrics that alluded to tour trauma, laudanum abuse, an unhappy love affair and emergent mental illness. None of this made for a pleasant picture, but in line with Nigel Spencer's oft‑quoted observation that "Pain is genius,” it did lend itself to a landmark double album whose entire fourth side would comprise the radical 'Three Piece Suite'.

With the Thwing Abbey sessions for Tipping The Scales scheduled to commence in April of 1971, the Zebra attempted to hire the Rolling Stones' mobile studio. That, however, turned out to be fully booked, so they used Graham King's industry connections to borrow a mobile truck from Mungo Jerry. By now, Stuart Nash was experiencing full‑blown paranoid delusions, and so while the band members all agreed to produce themselves he insisted that the album's engineering should be handled by someone they already knew. Enter their old friend from Finchley, Kevin Byrne.

Given his complete lack of professional recording experience, Byrne was an unlikely choice, yet Nash favoured him due to his interest in electronics and the fact that he had presided over the recording of early demos by the What? Hailing from a more working‑class background than the other two men, Byrne had left Finchley for an apprenticeship with the MOD at the same time that Nash and Spencer had departed for art college, and via his work with radar he had acquired a solid background in electronic engineering, while also dabbling in playing the guitar and bass.

"In my spare time, I really loved designing and constructing sound‑processing boxes, using parts that I scrounged from anywhere and everywhere,” recalls Byrne, who used his first tape recorder at age 14 to record the What?'s practice sessions. "I'd sit down with my soldering iron at the kitchen table and sort of make things up as I went along, building machines that could be used for goodness knows what. Well, the guys were very interested when I told them about some of the things that I'd made, and Stuart in particular was dead keen to use them to bring an experimental edge to the new album.”

Increasingly at odds with "that strait‑laced bunch” at the MOD, Byrne didn't need much persuading to join the Zebra bandwagon.

"The only thing that made me think twice was Stuart's appearance,” Byrne remarks. "He was very different to how I remembered him. Yes, he was friendly and charming and very keen for me to get involved, but at the same time he was twitchy and constantly fidgeting. I could tell he wasn't getting much sleep.”

Thwings & Roundabouts

Spencer and Nash on stage at the Bath Festival Of Blues, 1969.

Spencer and Nash on stage at the Bath Festival Of Blues, 1969.

In the spring of 1971, Byrne arrived at Thwing Abbey, eager to familiarise himself with the Mungo Jerry mobile that was centered around a custom mixing console and a Studer A80 eight‑track analogue tape machine. The rig also came with a selection of Neumann and Shure mics, Pye compressors and Vortexion outboard gear, along with Tannoy monitors that were powered by Quad amps.

"Thwing was beautiful,” he says. "The house itself was a bit run-down, but it was located in this great big park with an ornamental lake, and it was miles from anywhere, so you could make as much noise as you liked. It was exciting. Everyone was pleased to be there — the sun was shining and I think we all felt like we were on holiday.

"Stuart had a vision for Tipping The Scales. It was a bit blurry in places and sometimes it seemed a bit dark or maybe even illegal, but it was his vision and he stuck to it doggedly. A big part of the vision was doing whatever felt right at the time — it was quite a spontaneous vision — and he also wanted to push things as far as he could with the recording. I suppose everybody did at that time, but he was determined to take it further; to just do whatever it would take to make an album that sounded like nothing that had ever been heard before.

"Things got pretty experimental and we did get some pretty amazing stuff, but I also think we wasted a lot of time. For instance, we spent an entire day recording Stuart sitting under an apple tree in complete silence, waiting for an apple to drop. At around five o'clock in the morning, Nige said, 'Stuart, it's f**king April. We're going to be sitting here until f**king autumn waiting for your f**king apple to drop!' Looking back, it all seems so ludicrous. We didn't see Stuart for the next two days, he just hid in his room and sulked.”

It was at times such as these that a lot of the backing tracks were completed, with Kevin Byrne dipping into his goodie bag of homemade gadgets and devices.

"Several of them did some pretty extraordinary things to audio,” he says proudly, "including one that took a completely different approach to filtering. I called it my 'all things must pass' filter. However, the device that the band liked most was this thing we called the 'Red Box'. You see, it was red, and it was also only half‑finished when I took it down to Thwing. I can't now remember what it was actually supposed to do, but it had a bypass switch that I'd mucked up slightly, so when it was bypassed it made the signal a tiny bit louder. The band thought it was great as soon I turned it on, and they immediately made me use it on all the tracks. They didn't understand that it didn't do anything, they just thought it was great because it made everything louder. They used to call the bypass switch the 'magic button' and they'd dance around like kids, going 'Press the magic button, Kev! Can I press the magic button, Kev?' Silly sods!”

Zebra Rampant

The track sheet from 'Karla' — Byrne meticulously documented the recordings at Thwing Abbey.

The track sheet from 'Karla' — Byrne meticulously documented the recordings at Thwing Abbey.

With Nash's behaviour teetering precariously between the erratic and the downright peculiar, the sessions grew increasingly fraught, and Byrne soon found himself cast in the unenviable role of technological‑wiz‑cum‑technocratic‑nursemaid. Sample the infamous 'pony incident', when Nash entered the control room with a young colt and stunned his bandmates by announcing that they had all been sacked.

"They were gobsmacked,” Byrne confirms, "but by that point they were also getting so tired of it all that they were probably just glad to take a break. We spent the next two days trying to record the pony, and Stuart was going spare because it couldn't play in 6/8. It was almost funny to start with, but it turned into a bloody nightmare. Stuart was just shouting at that horse, getting really angry, there was shit everywhere — we were getting nowhere. In the end, it bit him and he got rid of it. Then he got strung out about the wallpaper in the drawing room. He said it was so loud, he couldn't hear himself sing. He and John stayed up all night, getting completely wrecked on speed while they peeled off every last bit of wallpaper. In fact, you know those weird rumbling sounds at the start of 'Three Piece Suite'? That's them stripping the paper with the tape slowed right down. Since there was no stopping them, I thought we might as well record it and then just edit out all of the grunting and muttering.”

While Byrne spent a lot of his time trying to figure out how to get the equipment to work, he also had to deal with an increasingly eccentric singer/guitarist who had decided that the console was an altar and needed to be adorned and treated with respect. Accordingly, after his fellow Zebras had been dismissed from the studio along with their recording engineer so that Nash and the desk could enjoy some quality bonding time, they returned the next day to find candles all over the console, along with the robes that he expected them to wear.

"He'd made them out of the purple velvet curtains in the drawing room,” Byrne says. "That whole 'veneration of the blessed mixer' was bizarre, but we had to humour him just so that we could get some bloody work done.”

'Karla'

This included the aforementioned 'Karla', which starts with an unusual, reflective Hammond organ intro followed by delicate guitar arpeggios that support Nash's initially introspective vocal. The song then shifts up a gear as the rhythm guitar, bass and drums kick in, building through the bridge to the now‑familiar anthemic chorus that is driven by the inexorable rise in pitch and volume of the lead vocal, while massed backing vocals and assorted sound effects add to the other‑worldly feel.

"'Karla' is my favourite song on the album, but it wasn't an easy one to finish,” Byrne states. "It went through lyrical rewrites as fast as Stuart went through girlfriends, and even the title was changed — originally, it was called 'Ariadne', so when Stuart changed this to 'Karla' the entire chorus didn't scan properly and at one point he had to hold the 'l' in Karla over four whole bars. I've been told the Manic Street Preachers were very influenced by this.

"The funny thing is, I don't remember there being any microphones involved. But looking back, there must have been. The names escape me right now, but there were definitely some longish, pointy ones and a few short, stubby ones about the place. Given Stuart's vocal style, it really didn't make a lot of difference, to be honest! My forté was the stuff I made myself; I had trouble getting interested in commercial gear.

"I'd read about optical compression, where the signal lights up a little bulb that shines on a photo‑resistor and reduces the gain. I found out you can also get resistors that are sensitive to heat, so I thought maybe those would work, and they did, kind of, although they needed a lot of power. You see, as Stuart's vocal style grew more and more eccentric, I needed more and more compression. Eventually, I soldered a jack input onto a Baby Belling electric cooker and that did the job. Then, later on, we used the MkII, which had balanced XLRs and a wok attachment. If you listen closely to 'Karla' you can actually hear a drop in level halfway through the second verse — that was where John put the kettle on in the middle of a take.”

Nigel Spencer, meanwhile, used his newly acquired Hammond C3 to write an additional section for the 'Karla' intro, just before the drums appear. Recorded with plenty of tape delay, this fits perfectly with Graham King's lead guitar and Stuart Nash's one‑chord drone.

"The rhythm guitar went through the Leslie,” Byrne recalls. "And you know that weird echo effect on Graham's lead part? The one that sounds like a tunnel? It is a tunnel! We went to a railway tunnel in the middle of the night and we played back the guitar part just to get that echo.”

Decline & Fall

When the Thwing Abbey sessions finally came to an end, Heavy Zebra were no longer signed to Liberty Records but to United Artists, which had been merged with Liberty several years earlier and now took control of the entire roster. Baffled by what they regarded as a weird end product, UA assigned a miniscule budget to the marketing of Tipping The Scales, and this, together with its lukewarm reviews and the band's refusal to tour, resulted in lousy sales both for the album and the 'Karla' single.

Disconsolate over the mainstream failure of his magnum opus, Stuart Nash subsequently became hooked on the laudanum that he'd been using to cope with his headaches, and after another album, 1974's Crossing, met with even less interest, he disbanded Heavy Zebra, changed his name and left the music business forever. Over the past three decades there have been several unconfirmed sightings — erstwhile fans are said to have spotted him playing guitar at a Turkish beach bar, roadying at the Malvern Folk Festival and even alongside Elvis in the Ramsgate branch of Burger King. However, there has been no contact with his former colleagues: Nigel Spencer, who is now a sheep farmer in Wales; John Collins, who retrained as an architect in East London; and Graham King, who in addition to his successful Macclesfield‑based painting and decorating business, has recently started a Heavy Zebra tribute band with Spencer. Called Loaded Gnu, this gigs several times a year.

"I am proud to have made that album with them,” says Kevin Byrne, who returned to the MOD after his traumatic experience recording Tipping The Scales. "I am proud to have survived making that album with them. But I've got to say, I never want to do another one. It's just incredible to hear how some of pop's biggest groups have been influenced by a record that we made nearly 40 years ago, and there are nights when, tooling around in the kitchen, I just think to myself: what does Stuart make of all this?”

Artist: Heavy Zebra

Track: 'Karla'

Label: United Artists

Released: 1972

Producer: Heavy Zebra

Engineer: Kevin Byrne

Studio: Thwing Abbey

Bass Glue...

Byrne expresses satisfaction with the sound that he obtained from Nigel Spencer's bass on Tipping The Scales, and there can be no denying that it does, indeed, hold the entire record together. However, there was an interesting reason for this...

"To begin with, we miked up Nigel's bass cab, but I didn't exactly know what I was doing with that sort of thing,” Byrne now admits. "I was fine with the technical side, the electronics side, but I reckon a more experienced engineer would have just known where to put the mics. That's probably why a lot of the album sounds so odd — half the time I didn't have a bloody clue what I was doing! Still, I've always suspected that's why Stuart hired me. He could be pretty clever... and he could also be a bit of a sh*t!

"We actually had to stop miking Nige's bass fairly soon after the sessions had started because his amp disappeared. It turned out that Stuart had flogged it and used the money to buy everyone shoes. I remember him coming back really happy, handing them out as though he'd done a really nice thing. He didn't seem to realise they were children's shoes. Anyway, that's why the bass sounds like it does — it went straight into the desk because we didn't have a bass amp, yet it's probably the only properly recorded thing on that entire album.”