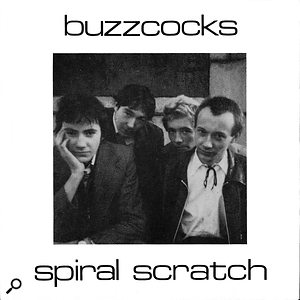

Buzzcocks, early 1977. From left to right: Howard Devoto, John Maher, Steve Diggle, Pete Shelley.Photo: Kevin Cummins/Getty Images

Buzzcocks, early 1977. From left to right: Howard Devoto, John Maher, Steve Diggle, Pete Shelley.Photo: Kevin Cummins/Getty Images

Engineer Phil Hampson didn’t even like punk rock — yet, with an inexperienced Martin Hannett, he recorded one of the defining records of the era.

Although released three months after the Damned’s ‘New Rose’ and two months after the Sex Pistols’ ‘Anarchy In The UK’, many consider Buzzcocks’ Spiral Scratch EP — released on the 29th January 1977 — to be the first true punk rock record. Not least because it was self–released by the Bolton band on their own New Hormones label and completely outside of the London–centric music industry. Originally pressed on to 1000 seven–inch vinyl copies, this rattling four–track punk classic, famed for its standout track ‘Boredom’, would go on to sell 16,000 through mail order and the Virgin chain of record shops.

The original four–piece line–up of Buzzcocks — singer Howard Devoto, guitarist/singer Pete Shelley, bassist Steve Diggle and drummer John Maher — was to splinter only months after the release of Spiral Scratch when Devoto, growing tired of the “cartoon–like” direction he felt punk was heading in, quit the band. “We had no idea whether we’d sell a thousand,” he says today. “I’d no idea that Spiral Scratch was going to take off in the way that it did. Not that it ever made me regret my decision, I have to say.”

Buzzcocks formed in early 1976, inspired by Devoto and Shelley seeing the Sex Pistols perform in London, who they went on to book to play at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester for two highly influential gigs in June and July that year, the latter of which featured their own group as openers. Soon after, they recorded their first demos at Revolution Studios in Manchester, later bootlegged in 1978 as the Time’s Up album, before finally being officially released in 2000.

“Revolution Studios was in somebody’s house in the suburbs of Manchester,” says Devoto. “It was up in the attic, so I remember us recording in a room where we were right under the beams of the roof. We decided we needed somebody on our side in the control room. Not that the people at Revolution who did Time’s Up were difficult, but we probably needed somebody else in there.”

Enter Martin Hannett, credited on Spiral Scratch as producer under the name Martin Zero. Hannett would go on to become a near–mythical figure as the pioneering — and domineering — producer of Joy Division and Happy Mondays (he died of heart failure in 1991 at the age of 42 due to alcohol and drug addictions). At the time, remembers Devoto, the nascent producer was a far quieter individual.

“Yes, that’s how I remember Martin,” says the singer. “This picture of him as this demonic dictator is just not something I recognise at all. I remember him as a relatively quiet guy huddled with the engineer.”

Indigo Sound

The engineer/mixer of Spiral Scratch was Phil Hampson, the in–house at central Manchester studio, Indigo Sound. For someone whose claim to fame would be overseeing a seminal punk record, Hampson had arrived at this point through an unlikely route. “I came into the business playing guitar and writing songs,” he says. “I had a couple of deals that came to nothing. I was recording in a studio called Morgan down in London which was quite famous at the time. By working in the studio, I got interested in the technical side of it, being a bit of a techie.

“As we came into the early ’70s, like a lot of other guys who were trying to make it in the music business, it wasn’t happening and I hadn’t got any money. So somehow I was able to con my way into an agency where they allowed me to set up a little demo studio and I learned on the job. I thought, well I can make a living as an engineer. Whereas, as a songwriter or a musician, you can make a very good living, but most people don’t. So it was a regular job.”

From here, Hampson opened another studio, Magnum, in Hyde, Cheshire. “We bought the mixing desk from Decca Studio Two,” he recalls. “It was quite a battleship but it had recorded the really early Stones hits and the Moody Blues. Decca designed and built it themselves and the manual was handwritten. This is now 1972 onwards and those years we had a lot of guys who’d been big–ish in the ’60s who were not exactly on the way down, but whose fortunes had changed a bit. Alvin Stardust had contractual commitments to provide tracks and he would come in and we would work at night because it was cheap. But I worked with Wayne Fontana, Billy J Kramer, Freddie & the Dreamers. They’d come down I suppose from where they were.

Martin Hannett in the studio, 1980.Photo: Kevin Cummins/Getty Images“We bought this Scully eight–track from Strawberry Studios and it did a grand job for the time. Strawberry had been using it until they had their first big hit with Hot Legs [‘Neanderthal Man’ in 1970] and then they decided to upgrade to a 16–track for all the 10cc stuff.”

Martin Hannett in the studio, 1980.Photo: Kevin Cummins/Getty Images“We bought this Scully eight–track from Strawberry Studios and it did a grand job for the time. Strawberry had been using it until they had their first big hit with Hot Legs [‘Neanderthal Man’ in 1970] and then they decided to upgrade to a 16–track for all the 10cc stuff.”

In the summer of 1976, Hampson began working at Indigo Sound, a higher–tech studio in the heart of Manchester. The fact that it was situated directly across the road from Granada TV’s studios meant that its clientele was largely made up of comedians and cabaret bands. “We were recording all manner of people,” Hampson recalls. “Syd Little and Eddie Large, Cannon and Ball, the Dooleys. Granada had a pop programme, and the Musicians’ Union went through a phase of saying they would not allow people to mime on live television shows. So they said, ‘You’ve got to re–record these chart–topping songs.’ A lot of big names then were coming in and had to recreate in a couple of hours these hit records.”

The setup at Indigo Sound was based around an Ampex MM1100 16–track two-inch machine and an 18-channel Sound Techniques desk. “The studio was in the cellar,” Hampson explains. “There were two large recording rooms, which made life difficult in some respects, simply because of communication. We actually did full orchestras in there from time to time, squashed them in, and there was a drum booth in the bigger room, but it was easy to get separation by using the two rooms. It was a reasonably good acoustic, but with a low ceiling — for a studio anyway: it was under eight foot.”

Noise Annoys

Hampson remembers that the connection to Buzzcocks and Hannett was made through the studio’s tape op, Mike Thomas, and that the session was booked between Christmas and New Year 1976. “Mike said, ‘I’ve got some mates and they want to come in,’” says Hampson. “The studio owner was classically trained and not the kind of guy you would want to get involved in that kind of music. I was more so, even if I wasn’t a youngster myself. He said, ‘Look could you come in and do the session?’ I didn’t particularly want to come in between Christmas and New Year, but I remember the day and these guys rolling up. I really wasn’t prepared for the noise that came out.”

Not being familiar with punk rock, when Buzzcocks set up and began to play, Hampson was astounded by how distorted their sound was. “Let’s face it, a big part of that music was making noise,” he points out. “It had to be loud. And of course that’s great when you’re on stage. But this was a new discipline really, when you go into a studio. My feeling as always is that you’re there to capture a performance, so you can’t say, ‘Hang on, you’re in a studio, so turn down.’ As an engineer you’ve got to think, well that’s what’s happening, I’ve got to try and reproduce that as faithfully as possible. They did play loud and then obviously you had to adjust things so the mics weren’t overloaded at the front end. I would never have said (and I don’t think they would’ve stood for me saying) ‘I’m sorry, you’re playing too loud, turn down.’”

Mic–wise, Indigo Sound had a fairly limited selection: AKG 414, 412, C12A and D12, Sennheiser 441 and Calrec CM1050. “The Calrec went on the snare,” Hampson says. “The 414 or the 412 we would use for vocals. For the drums, typically, it was Sennheiser and Calrecs mainly. I did a full rig, seven mics usually. Snare, bass drum, a couple of overheads and we’d pick out the hi-hat and then as many toms as we felt was necessary. The Calrec and Sennheisers could stand the pressure levels. One of the factors apart from the cost of buying mics was they had to be robust. That kind of jobbing studio, people would be in and out and a typical session was three hours. Things would get thrown around and anything that was too delicate would simply not stand up to the job. We always had the D12 on the kick drum and that would stand up to any kind of abuse.”

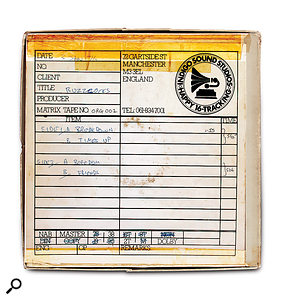

The tape box for the Spiral Scratch EP. The master tapes were reused by the studio, possibly to record Little & Large...Using the two live rooms, along with the drum booth and with Steve Diggle’s bass amp positioned in a corridor, Hampson managed to get separation between the sounds. Howard Devoto remembers that, gear–wise, the band’s equipment was fairly basic. “Pete would have been using his Puma,” he says, “the cheap guitar he had that the top had got knocked off. They were using H/H amplification.”

The tape box for the Spiral Scratch EP. The master tapes were reused by the studio, possibly to record Little & Large...Using the two live rooms, along with the drum booth and with Steve Diggle’s bass amp positioned in a corridor, Hampson managed to get separation between the sounds. Howard Devoto remembers that, gear–wise, the band’s equipment was fairly basic. “Pete would have been using his Puma,” he says, “the cheap guitar he had that the top had got knocked off. They were using H/H amplification.”

At this stage Martin Hannett hadn’t done much recording and Hampson got the impression that he didn’t really know what he was doing. “He didn’t, by his own admission,” he laughs. “But he’d been gaining a reputation. He had sat in on sessions at a couple of local studios, but the thing was he was new to the discipline of recording, I guess. This was a common thing at this time that people would come in with bands. The idea of producing records was very appealing and you had these mythical figures who were called producers. People around the music scene who knew bands who possibly weren’t musicians themselves thought, ‘this is good, this is a role I can fulfil’. And so it happened quite a lot where a band would come in with somebody they knew who maybe talked a good game or maybe had an exceptional ear for recording music. It wasn’t unusual to see people sat there who were producers. And that was fine, we were quite happy to do that.”

Nevertheless, Hampson remembers that, on the session, Hannett’s inexperience revealed itself when he kept trying to push the faders on the desk, distorting the preamps. “Distortion is one thing but that wasn’t good distortion,” Hampson reasons. “So I was pushing them down and saying, ‘Look, no, if you want to hear more of that you turn up the monitor knob.’ He was learning I guess at that time and wanting to understand what was going on in the control room.”

Similar to how Devoto remembers him, Hampson says Hannett wasn’t a particularly vocal character. “He was quite quiet. I think maybe as things went on and he did gain a reputation then he became more confident and more able to sort of go off–piste as it were and try things that perhaps weren’t conventional. That’s what genius is usually about. But at this point he was more in a sort of learning phase than anything else.”

As far as the band themselves were concerned, if Buzzcocks were slightly intimidated by being in a proper recording environment, they never let it show. “We were probably fairly good at putting on a front of bravado,” laughs Devoto.

Boredom

On the back cover of Spiral Scratch, in a typically punk move, Buzzcocks attempted to demystify the recording process by listing the take number and overdub details of each song: ‘Breakdown’ (third take, no dubs), ‘Time’s Up’ (first take, guitar dub), ‘Boredom’ (first take, guitar dub), ‘Friends Of Mine’ (first take, guitar dub).

“‘Breakdown’ would have been the first song that we did,” says Devoto. “We maybe did three takes while they got the levels and sorted out the sound. We definitely had this approach of doing it quick and as live as we could. Having that kind of attitude protected you against the trepidation you might feel about the technical side of it. You’ve already established some limits, as it were: ‘We’re gonna do it this way.’ But we did want to do the dubs, having done the Time’s Up demos where Pete just did the guitar solos along with the rhythm guitar track. We felt that could sound better and if he could keep the rhythm going and then just dub on the guitar solos, then that would probably be an improvement.”

Phil Hampson today.Famous for its brilliantly minimalist two–note guitar solo, ‘Boredom’ stood out on Spiral Scratch, possibly because it had the most ‘punk’ of lyrical sentiments. “I think it was probably the catchiest,” says Devoto. “The good old melody thing, y’know. ‘Boredom’ was written late summer/autumn ’76 and it was slightly more sophisticated in that it had the stop in it. Up to that point, to my mind, punk songs, they started and they ended. That was my contribution, which was to have this dynamic stop. Pete came up with that great little hook on the chorus, singing ‘Boredom’, and people picked up on that. We had the Clash saying to us that when they were on tour, their bus driver was called Norman and so they’d be singing, ‘Norman... Norman’ [to the tune of Boredom]. We didn’t think that was the star song on it, as it were. It was just another song in a way.”

Phil Hampson today.Famous for its brilliantly minimalist two–note guitar solo, ‘Boredom’ stood out on Spiral Scratch, possibly because it had the most ‘punk’ of lyrical sentiments. “I think it was probably the catchiest,” says Devoto. “The good old melody thing, y’know. ‘Boredom’ was written late summer/autumn ’76 and it was slightly more sophisticated in that it had the stop in it. Up to that point, to my mind, punk songs, they started and they ended. That was my contribution, which was to have this dynamic stop. Pete came up with that great little hook on the chorus, singing ‘Boredom’, and people picked up on that. We had the Clash saying to us that when they were on tour, their bus driver was called Norman and so they’d be singing, ‘Norman... Norman’ [to the tune of Boredom]. We didn’t think that was the star song on it, as it were. It was just another song in a way.”

Mixed Memories

Spiral Scratch was recorded and mixed in a three–hour session, with Hampson leaving Hannett and the band to do the mixes while he went to the pub. “Mike Thomas mixed it with Martin,” he says. “But the problem was, Martin not being used to the room and not being used to mixing and what was important and what wasn’t, it was felt subsequently by the band that they weren’t totally happy. That always happened: you’re in the studio, you’ve got lovely loud monitors and everything sounds great and the way you want it. Then you do a cassette as we did then and they would go and put it on in the car or go home and they’d say, ‘Well that’s nothing like I heard in the studio.’ That happened a lot with people who weren’t used to it, and often it was just a case of not being used to the room that you were mixing in and knowing what to compensate for. Which, obviously, if you were there working all the time, you knew.”

Hampson and Devoto’s memories differ when it comes to what happened next. The former remembers he went back into the studio alone on the 3rd January 1977 and remixed the tracks for free. The latter insists he and Pete Shelley were there.

“Mike said, ‘Look they’ve no more money and they’re not happy with the mixes,’” Hampson remembers. “I said, ‘OK, leave it with me. I’ll go in one night and I’ll have a listen to everything.’ I was putting additional effects on there. Compression and some echo. I do remember there was something that had happened at the end of ‘Boredom’ that I had to mess around with. I had to extend it and just try to mask something that was there. I put this long tail on it. I messed around with that for ages to try and get a clean long tail just using the Audio Design compressor and MRX digital repeat.

“I certainly just cleaned it up in terms of EQ and passed the mixes back to Mike to give to the band and that was what they used to press from. I was pleased really ’cause obviously they’d got a good deal. It’s horrible when you’ve put money and time and effort and excitement into something and you’re not happy with the end result. It’s a horrible feeling. We’ve all been there.”

Devoto meanwhile remembers that the echo at the end of Boredom was more a creative decision and not one made to cover up a mistake. “That sound idea was mine,” he says. “I’m sure I said, ‘Can’t we make some kind of noise to carry it on and keep the kind of dynamic going until ‘Friends Of Mine’ comes in?’ I’d have been there at the mixes and I’m sure Pete would have been at the mixes.”

One thing that Devoto recalls very clearly is that Hampson didn’t seem very impressed by the music that Buzzcocks were making. “Towards the end of it, I turned to him and said, ‘Well what do you think of it?’” he remembers. “He had a sort of panicked look in his eye and said, ‘Erm, it’s not really my kind of thing.’”

“This was my first experience of recording this genre of music,” says Hampson. “Having had the experience of doing that, I thought, ‘Well this ain’t my kind of music’. Basically, although I was just a few years older, I was older enough not to be moved by it in the way that the kids at the time were. But then the word got around about the success of what Buzzcocks were doing and there were other bands like Slaughter & the Dogs and V2 came in and I subsequently did quite a few tracks like that. But if I’m honest it was never my favourite music.”

Afterwards

For very different reasons, both Howard Devoto and Phil Hampson were to walk away from punk soon after the release of Spiral Scratch. Pete Shelley stepped into the role of lead singer of Buzzcocks and led them through a successful run of hit singles including ‘What Do I Get?’ and ‘Ever Fallen In Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve)’. Devoto returned to college for a year before re–entering the music business, fronting the more artful, post–punk, Magazine.

For him, his decision to walk away from Buzzcocks was partly due to punk, in his mind, quickly becoming a shtick, and partly because the gigs were becoming increasingly violent. “Yes, I was getting fed up of it,” he says. “It was also getting a bit scary. The spitting thing continued for really quite a long, long time when Magazine had started. So, yeah, something of an ordeal.”

Phil Hampson, meanwhile, began to earn a reputation for making novelty records, not least Brian & Michael’s 1978 number one, ‘Matchstalk Men & Matchstalk Cats & Dogs’. “I moved on in style and I was doing novelty records and all that crap,” he laughs. “‘Matchstalk Men’ was number one for three weeks and did 800,000 records. Subsequently I went downhill. I did the talking dog from the Esther Rantzen show [1979’s ‘Sausages’ single by Prince The Wonder Dog]. It just went silly. But I love crap like that because in its own way it was a similar kind of thing of sticking two fingers up to the business.”

When Hampson found out how much Spiral Scratch had actually gone on to sell, he was astonished. “It was amazing,” he says. “It was just indicative of the power of that movement at the time. There was a great element of people wanting to be part of that. It was partially a social revolution as well as a musical one. A lot of kids would listen to that and think, ‘Well actually I could do that’. I just think a lot of people respected that and wanted to be part of that and adopted that culture and maybe that’s partially why it sold so many. It was a movement. I’d had experience of bands making records and usually it was just in the hundreds that they would be able to sell them, even if they were appearing live and selling them at gigs, as a lot of cabaret bands used to do. It’s amazing because there was no social media then. It was all word of mouth.”

When Hampson found out how much Spiral Scratch had actually gone on to sell, he was astonished. “It was amazing,” he says. “It was just indicative of the power of that movement at the time. There was a great element of people wanting to be part of that. It was partially a social revolution as well as a musical one. A lot of kids would listen to that and think, ‘Well actually I could do that’. I just think a lot of people respected that and wanted to be part of that and adopted that culture and maybe that’s partially why it sold so many. It was a movement. I’d had experience of bands making records and usually it was just in the hundreds that they would be able to sell them, even if they were appearing live and selling them at gigs, as a lot of cabaret bands used to do. It’s amazing because there was no social media then. It was all word of mouth.”

Years later, Hampson was at a party in West Palm Beach in Florida, surrounded by hipster 30–somethings who were playing British records from the late ’70s and early ’80s. When he casually informed them that he’d helped to make Spiral Scratch, he suddenly found himself being treated as if he was a living legend. “It surprised me, to be honest,” he admits. “It was in the States when it came home to me. This guy said, ‘I’ve seen [Michael Winterbottom’s 2002 film about the Manchester music scene] 24 Hour Party People 30 times’ and he started playing some of it. I said, ‘Well, I actually recorded that.’ The people were falling around and it was like sort of worship. I thought, this can’t be right. I had no idea.”

Devoto, meanwhile, has mixed feelings whenever he hears Spiral Scratch these days. “I think it kind of sounds rather thin in terms of the production,” he says. “But I still think it’s pretty good. It’s a great little package of four songs.”

An interesting footnote to the story is the fact that, because the tape on the session was only hired, the master of Spiral Scratch was subsequently recorded over, quite possibly by Little & Large. “The two–inch tape of course was used again, as it was in those days if you didn’t buy the reel,” says Hampson. “That’s what studio owners did. It was no doubt over–recorded by Syd Little and Eddie Large or something equally bizarre.”

“I feel that’s fine,” says Devoto. “We didn’t stump up for it. To me, that goes along with us not knowing if we were gonna sell a thousand copies. That’s the way it goes. It’s funny. There’s something very levelling about it all.”

Phil Hampson feels the whole tale of Spiral Scratch passing into rock history only goes to prove that, as a studio engineer, you really have no idea which of your recordings will stand the test of time.

“I had sort of moved on to more rubbish,” he says, “and I never gave it much thought at the time. It had been yet another session, and it could have been yet another session that never saw any end result. But in this case, it’s the one that happened to work.”

Artist: Buzzcocks

Record: Spiral Scratch

Label: New Hormones

Released: 1977

Producer: Martin Hannett

Engineer: Phil Hampson