The story of Don McLean's 'American Pie' goes from cryptic beginnings to massive chart success, and an eventual position as a perennial US radio favourite.

Don McLean playing live in Amsterdam.Photo: Retna

Don McLean playing live in Amsterdam.Photo: Retna

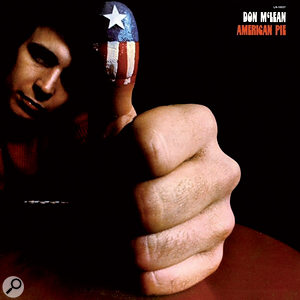

If ever a song's lyrics have been interpreted, reinterpreted and misinterpreted, it is those to Don McLean's 'American Pie'. This eight and a half minute, folk-rock epic, split over two sides of a single and leading off McLean's eponymous second album, has been a three-million-play US radio staple and the subject of ongoing speculation ever since its initial release in November 1971, which saw it reach number two in the UK and become the longest recording to ever top the Billboard Hot 100.

Just about the only person who hasn't contributed a whole lot to the discussion is the artist himself who, in 1993, wrote an explanatory note to the Chicago Reader, published in its syndicated column 'The Straight Dope'. "Sorry to leave you all on your own like this,” McLean stated, "but long ago I realised that songwriters should make their statements and move on, maintaining a dignified silence.”

In other words, to preserve the song's hallowed status and sustain listeners' interest, keep 'em guessing. Probably a smart idea. In the same letter, McLean also said the one reference he has admitted to is that pertaining to rock & roll pioneer Buddy Holly in the opening stanzas:

"I can't remember if I cried, When I read about his widowed bride, But something touched me deep inside, The day the music died.”

This last line actually refers to Tuesday, 3rd February, 1959, when Holly, singer‑songwriter Ritchie Valens and DJ/singer-songwriter JP 'The Big Bopper' Richardson were killed in a plane crash near Clear Lake, Iowa, during a three‑week concert tour of the Midwest.

As Don McLean told the Chicago Reader, "I dedicated the album American Pie to Buddy Holly as well, in order to connect the entire statement to Holly, in hopes of bringing about an interest in him, which subsequently did occur.”

Essentially, in addition to the ditty being McLean's cathartic means of paying tribute to his late, lamented hero, it also provides a potted, allegorical history of rock music through to the end of the 1960s, while ruminating on Western pop culture's loss of hope and innocence during the second half of that turbulent decade. Musicologists, reviewers and radio and TV pundits have dedicated countless column inches and hours of air time to debating the metaphors and identities of the song's colourful cast of characters. And while this discourse continues — in line with McLean's implied intention — there is a general (if not always unanimous) agreement about much of the symbolism.

Busking It

'American Pie' producer Ed Freeman in the early 1970s.

'American Pie' producer Ed Freeman in the early 1970s.

The song itself, as well as the associated album, was produced by Ed Freeman, who, growing up in Boston, learned to play the violin, classical guitar, folk guitar and renaissance lute, before becoming a performer on the local folk scene. Nevertheless, disenchanted with performing, as soon as he recorded in a studio he knew that he'd prefer to work behind the glass rather than in front of it, and when encountering Tom Rush at a party, he persuaded the folk and blues singer-songwriter to let him produce Rush's self-titled 1970 album for CBS.

"I talked fast,” Freeman now jokes. "Before that, I was in a group that was signed to Capitol Records — I was signed as a songwriter — and then I'd gone into arranging. Frankly, I was a really good bullshit artist. When the group disbanded, I didn't have any money, our producer Nick Venet casually mentioned that he needed an arranger for something, and so I said, 'I'm a great arranger!' 'Oh, really?' he asked. "What have you done?' I told him I'd written several symphonies, some chamber music and pieces for string quartets, and he said, 'Great. We need a string quartet and two Bach trumpets for tomorrow at 7:00pm. Here's the tape.'

"At that time, I didn't really know how to read and write music. So I quite literally ran out of Nick Venet's office and down the street to a bookstore, where I bought a book on arranging. I read it that afternoon, wrote the arrangement that night and, on the basis of managing to please the producer, I then wrote a bunch of other arrangements for him, before landing a little production gig, that led to the Tom Rush project, that led to Don McLean.”

Tapestry, McLean's 1970 debut album featuring his compositions 'And I Love You So' and 'Castles In The Air', had been produced by Jerry Corbitt, guitarist with folk-rock outfit the Youngbloods. However, impressed by Tom Rush, McLean asked Freeman to helm the follow-up.

"He sat in my living room and played me the first verse and chorus of 'American Pie',” Freeman recalls. "I thought, 'That can be a hit record'. Then he finished it and I thought, 'Well, it could have been a hit, but it's way too long.' Actually, I remember turning to his manager and saying, 'That's all well and good for an album, but what are we going to do for a single?' The manager said, 'We're going to release 'American Pie',' and I said, 'You've got to be kidding.' By then, they had already shot the photo for the album cover and named it American Pie.”

Engineer Tom Flye working on the boxed set All Good Things: Jerry Garcia Studio Sessions in 2003.Photo: Dave GansNot that Don McLean had been concerned with any of this when writing the song. For years, the Tin & Lint bar in Saratoga Springs, New York, has laid claim to 'American Pie' initially being penned there, and it even has a plaque commemorating this historic event above the table where McLean was supposedly boozing and scribbling phrases like "Drove my Chevy to the levee” on paper napkins during the course of a summer night in 1970. Several people insist they were there and that, after the composer drunkenly left his lyrical notes behind, a student gathered them up and returned them to him. In a number of interviews, Don McLean has categorically denied this and repeated that he wrote the song not in Saratoga Springs, but in Cold Spring, New York, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, before performing it for the first time at the latter city's Temple University, where he was opening for singer-songwriter Laura Nyro.

Engineer Tom Flye working on the boxed set All Good Things: Jerry Garcia Studio Sessions in 2003.Photo: Dave GansNot that Don McLean had been concerned with any of this when writing the song. For years, the Tin & Lint bar in Saratoga Springs, New York, has laid claim to 'American Pie' initially being penned there, and it even has a plaque commemorating this historic event above the table where McLean was supposedly boozing and scribbling phrases like "Drove my Chevy to the levee” on paper napkins during the course of a summer night in 1970. Several people insist they were there and that, after the composer drunkenly left his lyrical notes behind, a student gathered them up and returned them to him. In a number of interviews, Don McLean has categorically denied this and repeated that he wrote the song not in Saratoga Springs, but in Cold Spring, New York, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, before performing it for the first time at the latter city's Temple University, where he was opening for singer-songwriter Laura Nyro.

"'American Pie' is a little bit like the Mayflower,” he said in a December 2011 NPR radio interview. "Everybody has been on it or their parents were on it or something. People knew me that I didn't know, and people know things about me that, you know, that they imagine, and it's just the way things are... But what makes me think this is funny is that I've been kind of knocking these down for years and it persists. So, it makes you wonder, how can you believe history?”

After his introduction to Don McLean performing 'American Pie', Ed Freeman helped to assemble the core rhythm section that would record it — David Spinozza on electric guitar, Paul Griffin on piano, Bob Rothstein on bass, Roy Markowitz on drums — and set about arranging the track.

"I rented a rehearsal studio, put Don in there with Roy and Bob — who went on to play with Bob Dylan and is now named Rob Stoner — and we rehearsed the song for two weeks before we actually cut it,” Freeman says. "Don was very uncomfortable with the idea. He wanted to cut it with just the acoustic guitar. On the one hand, he liked the Tom Rush album, which was very produced, but on the other hand he didn't want his own album to be at all produced, so we had some differences of opinion there.

The Spectra Sonics desk in the Record Plant's Studio A.Photo: Roy Cicala, Bill Cheney"I wanted to capture the sound of a band that was really cooking, and for that I made a deliberate choice to not use a bunch of studio musicians who could act like a metronome and turn on like a faucet, without any feel. Instead, the people we used were good musicians but ones with not a whole lot of studio experience who, instead of doing a series of overdubs, would play together and provide us with an organic performance. Overdubs would have really driven Don nuts. He wasn't into that, so I said, 'Fine, but then we're going to rehearse this.'

The Spectra Sonics desk in the Record Plant's Studio A.Photo: Roy Cicala, Bill Cheney"I wanted to capture the sound of a band that was really cooking, and for that I made a deliberate choice to not use a bunch of studio musicians who could act like a metronome and turn on like a faucet, without any feel. Instead, the people we used were good musicians but ones with not a whole lot of studio experience who, instead of doing a series of overdubs, would play together and provide us with an organic performance. Overdubs would have really driven Don nuts. He wasn't into that, so I said, 'Fine, but then we're going to rehearse this.'

"Had we rehearsed the song with seasoned studio players, we would have gotten about three takes out of them before they fell asleep. They wouldn't have needed to play it a hundred times. However, to get Don integrated into the band we did need to do that. At that time he wasn't a seasoned player and the other guys weren't all that seasoned either. So it really was a case of creating a band. On the session, at the last minute, we then brought in Paul Griffin and David Spinozza, who were seasoned studio musicians capable of playing anything blindfolded without rehearsal.”

The Record Plant

The 'American Pie' session took place on 26th May, 1971, inside Studio A at New York's Record Plant, and sitting at the 32-input Spectra Sonics console was engineer Tom Flye. Born in Cincinnati, raised in Chicago and originally a musician who progressed from playing keyboards to drums in a variety of groups that were still known as pop combos during the late '50s, Flye gained his first mono studio experience in the Windy City, before relocating to New York in about 1964. There, as a drummer with a band called Lothar & the Hand People, he hooked up with film-maker and record producer Robert Margouleff and helped build Centaur Sound, a four-track loft studio that boasted one of the first Moog synthesizers.

A Lothar album project at the Record Plant on West 44th Street, as well as session work there, resulted in Flye being offered a full-time job by owners Chris Stone and Gary Kellgren, and it was after engineering records by the Impressions and Curtis Mayfield, as well as assisting on the Woodstock soundtrack album, that Ed Freeman asked him to work on the American Pie project.

Another view of the Record Plant's Studio A. In the background you can see the studio's Ampex MM1000, 440 and ATR124 tape machines. Photo: Roy Cicala, Bill Cheney

Another view of the Record Plant's Studio A. In the background you can see the studio's Ampex MM1000, 440 and ATR124 tape machines. Photo: Roy Cicala, Bill Cheney

"The Spectra Sonics board had a separate monitor system, so you could record on one side and play back on the other,” says Flye, while recalling that the Studio A control room also housed a 16-track Ampex MM1000 tape machine and Tannoy monitors, in addition to one-inch Scullys with 12-track heads.

"The Studio A live area was the biggest of the two rooms we had, measuring maybe 40 x 60 feet with a 25-foot ceiling, and it was oddly shaped because it was a Tom Hidley design, acoustically treated with hard/soft traps and a drum booth that was basically a platform with some gobos around it. A school bell was positioned under that platform. Nobody could hear the talkback, so if the producer wanted the musicians to stop, he'd ring the school bell.

"At the most, I only had three tracks for the drums, so on the kick I might have used an EV 666 and there would have been a pencil mic on the snare. Back then we had [Neumann] KM84s, which are OK for the snare but will break up if the guy plays really loud, which is why I later switched to [AKG] 452s. In those days, we also had a lot of [Neumann] U87s, so I almost always used a couple of them as overhead tom mics, while arranging them to make sure there was an adequate amount of cymbals.

"In the early days of multitrack recording, most of the producers really wanted that mono mix right off the bat. We'd record live, pretty much, and always have a mono machine going someplace in the background, because if they could get that, they loved it. So whatever we were doing, we were always mixing live. Then, when we started splitting up tracks, everybody had their own way of handling that. I always liked to have the bass drum separate, and then, if I had to make a stereo mix of everything else, it was OK. Well, Ed originally wanted 'American Pie' to start in mono and then go to stereo, but that wasn't really doable with the board we had, so I talked him out of it.”

While the bass guitar was recorded with a DI, a U87 was used for David Spinozza's electric guitar, and two more on the piano.

A Chance To Cut...

"Don McLean was in a booth, singing and playing his acoustic guitar along with the rest of the band,” says Flye. "For his vocal, I used another 87, and at some point I ended up making a Plexiglas baffle so that I could get a little separation between the guitar and vocal, while he could still see the fretboard. That way, I was able to maybe fix a line here or there without screwing up everything else.”

"Don's vocal was put together from 24 different tracks that we had to bounce together,” adds Ed Freeman. "He is an excellent, very, very talented singer, but someone had apparently made fun of him because he sang things with the exact same vocal inflections every time. So he decided to be more improvisational, and my estimation was that his improvisations just didn't work and were muddling up the song. In my head, I knew what it was supposed to sound like — I don't now remember how I arrived at that, but when I kept asking him to sing it in a certain way, he wouldn't do it. He wanted to play with it every time, inserting slides, melismas and other things that, to my mind, didn't fit. So we ended up recording him 24 times on 16-track tape and took different parts from different takes until I got every word the way I wanted it, without all the play, and I don't think Don appreciated that very much.

"As I said, he is an enormously talented guy, but while the music world has many talented people who can work by themselves, it also has many who can't, who really need an editor and need a producer because they can't bring out the best in themselves and edit that which needs to be edited. In Don's case, I think he was happy with the finished vocal, but he was not happy with somebody else having that much influence. I took a very heavy hand with him and frankly I don't think my people skills back then were particularly good. It was disturbing to his ego, and I completely understand that because I would have felt the same in his situation. I remember standing in the hallway with him, God knows how many times, and having conversations that started out 'The trouble with you is...' That was not the way to go for either of us, so we had quite a tempestuous relationship. Still, I think he was happy with the result, because he booked me to produce two other albums.”

So much for the idea of meticulously rehearsing the song so that it could be recorded quickly.

"Well, except for the first verse, which had a piano solo, I don't think there was a splice in the rest of the backing track,” Freeman says. "Paul Griffin is an extraordinarily talented guy, but it turned out that he was really a violinist rather than a keyboard player. I had recently worked with him on a Carly Simon record, I thought he was great and I had no idea that he had only just started playing the piano. So when I stuck him in a room full of musicians and told him he was the solo pianist, he really wasn't up to it.”

"I remember specifically there were eight edits in that piano intro section,” adds Tom Flye, who also played tambourine on 'American Pie', drums on 'The Grave' and various other percussion parts. "It was a lot of work.”

"We took a chord from one take, a chord from another take and threw it all together,” Freeman continues. "My nickname at the time was Slash, because I wanted so many cuts — I was a monster when it came to editing tape. Now, when I listen to 'American Pie', I know where all of the vocal edits are, but there's only one where I actually smell a rat. One word is made up of three syllables and they come from three different takes. That's how picky I was about it, and I have to say that I was helped immeasurably in that regard by Tom Flye.”

"Cutting two-inch tape and putting it back together was kind of tedious and stressful,” Flye agrees. "However, I was a pretty good editor because I'd worked for a guy named Earl Dowd who made political-comedy records that required loads of editing. I'd have 50 pieces of quarter-inch tape to assemble for a single routine.”

"Tom is a total genius and also the most patient man I have ever met in my entire life,” continues Freeman. "Nothing will fluster him. I wasn't an easy person to work with, Don wasn't an easy person to work with, so working with the two of us together must have been like watching two wasps go at each other. Yet he was totally unflappable. He was endlessly, endlessly patient, and his personality was so perfect for the position, sitting there between these two monster egos — the producer and the artist. He was like the glue that held the whole thing together.

"Tom also has a ferocious ear. He would go into the studio and move a mic half an inch because he could hear the difference, and he would also come up with recording concepts that consistently worked. Technically superb, he could seemingly record anything, and I've seen him go through 50 different styles of music without even missing a beat. I frankly don't remember a lot of the technical things he did, but I do remember sitting there with him at three in the morning and going, 'Damn, Tom, that sounds good! What the fuck did you just do to that?' He's really an extraordinary person to work with, and without him I don't think we would have had anywhere near the kind of success that we did.”

Final Touches

For the song's final, campfire-type chorus, Don McLean was joined on vocals by what was credited on the album sleeve as the West Forty Fourth Street Rhythm and Noise Choir, an overdubbed ensemble comprising several of his personal and professional friends.

"I think a lot of people knew that this record was going to be a classic,” says Freeman. "So that background chorus — which I wanted a lot louder, but he disagreed — included Pete Seeger and James Taylor and Livingston Taylor and Carly Simon. It was quite a star-studded cast, and one that I really should have photographed.”

Not least since these days Ed Freeman's full-time career is as a highly successful photographer who has published two books of his widely printed, collected and exhibited work.

This aside, fitting an eight and a half minute track onto one seven-inch single presented a unique set of problems: "I didn't have much to do with mastering that record, but I know it was a nightmare,” remarks Ed Freeman. "It had to be cut very carefully in half, and even then each side was really long for a 45.”

The running times were 4:11 for Part One and 4:31 for Part Two.

"This caused problems with overcuts and all sorts of things,” Freeman says. "We had an abbreviated version, we had one that faded out and then faded back up for the second side — we tried everything, but thankfully people also ended up hearing the uninterrupted version by buying the album.”

Value For Money

The American Pie album, recorded and mixed during May and June of 1971, topped the Billboard 200 from 22nd January through 10th March of the following year. It is Don McLean's crowning achievement.

"Nick Venet, who had discovered me, was, by pure coincidence, the overseer of this project, even though he really had nothing much to do with it,” says Ed Freeman, who, just over 20 years ago, segued from a music career that also saw him work with Tim Hardin, Gregg Allman, Bonnie Bramlett, Roy Buchanan and New Riders of the Purple Sage to the aforementioned, ultimately even more satisfying one, in photography. "Don's first album, released by Capitol, was pretty good, but it hadn't sold all that well, so Nick told me, 'Look, this McLean asshole is a no-talent jerk. Your budget is $25,000. If you can make it for $20,000, I'll split the other five with you.' I said, 'No, thanks.' But then, when the work was over and I wanted to remix the record, I needed another $5000 for the studio time. United Artists were definitely not happy about that, but they did give in and I think they got their money's worth.”

'Vincent'

For all the plaudits that 'American Pie' has earned down the years, Tom Flye maintains that his favourite track on the album is 'Vincent', Don McLean's tender, heartfelt paean to troubled Dutch painter Van Gogh. Focusing on the man's talent, what he tried to convey via his art, and the lack of recognition that resulted in mental anguish and his self-inflicted death, McLean wrote the song after reading a Van Gogh biography, and it subsequently topped the UK charts.

"Ed Freeman wrote the string arrangement for 'Vincent' and that's one of his really strong points,” asserts Flye, whose current projects include an ongoing recording with Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart. "Ed's an excellent arranger who took his work very seriously.”

Not that the arrangement we hear on the record, with the strings appearing during the track's final verse, is the one that Freeman originally intended.

"The way I wrote it, they came in during the first chorus,” he explains. "However, Don objected to that quite a bit on the actual date, so I told the musicians to take 10 and rewrote the entire string chart.”

While we're unable to hear how the track would have sounded with strings throughout, it has to be said that the manner in which they delicately appear while McLean sings about "the ragged men in ragged clothes, the silver thorn of bloody rose,” adds an extra, atmospheric dimension that augments the singer-composer's conviction.

"What I said before about artists can also apply to arrangers,” Freeman concedes. "Just as an artist is not always, perhaps, his own best critic, that may be true for an arranger, too. The minute I started arranging things, every note of every instrument, I wanted the strings up loud and bury the vocal! So I was probably guilty of the same lack of perspective that anybody else who participates in a recording might be. To me, structurally it doesn't sound organic to have the strings come in near the end, because in a normal classical arrangement you wouldn't have the players sitting there twiddling their thumbs until the last verse. But, in terms of the emotion of the record, it may well be that Don was absolutely right. I'll leave that up to other people to decide.”