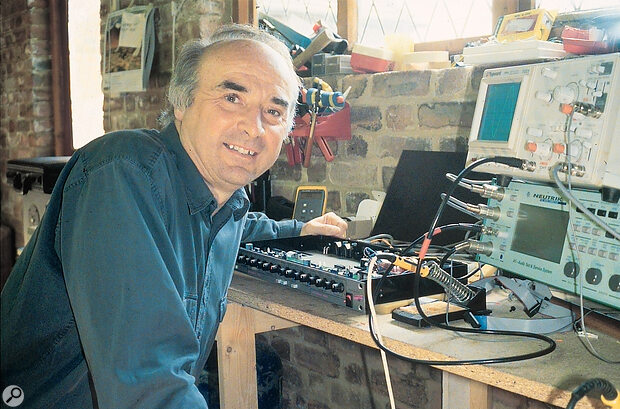

On the eve of the APRS exhibition, Paul White talks to Malcolm Toft, the man behind the legendary Trident range of recording consoles, who now has his own company, MTA, which looks set to continue the tradition of analogue excellence.

To anyone involved in professional sound recording, the name Malcolm Toft is synonymous with good‑sounding, well‑engineered mixing consoles. Unlike many console designers, Malcolm started his career as a recording engineer, first with Tony Pike music as a trainee, and two years later with CBS. In 1968 he joined Trident, where he was to work with a host of prestigious artists, including David Bowie and Elton John. During his time at Trident, Macolm spent much of his time working with producer Tony Visconti, for whom he still has much respect, and engineered David Bowie's Space Oddity album, three albums and two singles with T‑Rex, and James Taylor's first album. He was also the mix engineer on the Beatle's 'Hey Jude', which the Beatles chose to do at Trident because it was the only 8‑track studio around at the time!

By 1971, Malcolm Toft was manager of Trident Studios, and he convinced the management team that they could design and build a 24‑track recording console to fit the physical space available in the Trident control room. Malcolm was put in charge of the project, and by the time the design was complete one year later, other studios had shown interest in the console. It was soon realised that there was a future in console manufacture and so Malcolm hung up his engineer's hat and Trident Audio Developments was borne.

In 1981, Trident Audio Developments was bought by its management, Malcolm Toft and Jack Hartfield, who ran the company until 1988, when it was sold to Reylon plc. The conditions of sale effectively prevented Malcolm from building any more consoles for three years, so he set up a company to provide finance for the recording industry. Once the three years had expired, however, Malcolm's thoughts soon turned back to console design and in 1992, he founded MTA (Malcolm Toft Associates). Working on a relatively small scale, MTA began designing and manufacturing very high quality, split‑format analogue consoles at a time when other manufacturers were producing in‑line designs and looking at the possibility of all‑digital consoles. Before looking more closely at MTA, I asked Malcolm which of his earlier Trident designs he was particularly proud of.

Once people could buy digital tape machines, there was pressure to provide a digital console to interface to it, but if you think about it, a digital console is an entirely different kettle of fish.

"The 'A' range console we produced was certainly a ground breaker. Back in the early '70s, it was a very forward‑thinking console — as far as I'm aware, it was the first console to have EQ on the monitors, it had 10 aux sends and very comprehensive EQ on the input channel.

"There were problems with the 'A' range because we were very green at designing; it was all inductive equalisers. Somebody measured it and told us that there was about 170 degrees of phase shift! But the point was, and I think this is fundamentally important, that it didn't matter, because the EQ sounded good. One of the problems with current manufacturers is that they try to design out any phase shift or other anomalies, and end up with a product that has no character. We'd knock up a circuit on a breadboard, take it to the engineers at Trident Studios and see what they thought of it. Only when it sounded right would we then look at the spec."

On the face of it, EQ is a simple concept, in that you're simply applying different amounts of gain to different parts of the audio spectrum. Why do you think so much mystique has been built up around it?

"I'm a firm believer that a console's character comes not from technical specs, but from a philosophy of design. We use the same components as other manufacturers, but our mixers still have their own character. When we changed over from using discrete components in the 'A' range to ICs in the TSM, we were going into totally uncharted waters. The 'A' range circuitry had anomalies which gave it its character, and when we went from discrete components to ICs, a lot of people thought we'd lose our sound. Yet we managed to maintain the same warmth of EQ, the same type of sound. The reason was that we applied the same parameters to it. I don't think it matters whether you're using valves, transistors, op‑amps, whatever — the way that you design your circuits is what matters. Harmonics of at least twice the highest audible frequency appear to have an effect on what we actually perceive within the audio bandwidth, so we tend to go for a minimum bandwidth of 40kHz."

With MTA, you presumably see your niche still within high‑quality analogue consoles. What do you feel that your new consoles are bringing to the marketplace?

"The reason I started MTA was largely due to the popularity of the Trident Series 80, and the fact that there's no direct modern equivalent. Initially, my idea with the MTA 980 was to replace that console, but to add more contemporary facilities, because people in America were saying there was a market for it. There appears to be a great shortage of recording consoles in the mid price range that are built to last. It seems that consoles are now designed like Japanese cars with a life expectancy of two or three years because a newer model will come along and supersede them. I still believe that there's a lot of life left in analogue consoles, and that they will be able to compete with digital consoles on both price and performance for some time to come."

How long do you see the analogue mixer market holding up?

"If you'd asked me in the late '80s, I'd have said that we'd all have been digital by now, but that clearly isn't the case. When I went to the AES show in New York last year, I was staggered by the amount of retro equipment out there; everyone was looking for valve mic preamps or old Neve EQs and that kind of thing. There seems to be a backlash against digital, and people are seemingly dissatisfied with the clinical sound or the technical limitations."

Do you think that people have just started to wake up to the potential difficulties presented by all‑digital consoles? For example, the only way to get analogue signals in or out is via expensive converters, and you can't just plug digital signals into the desk without worrying about data formats, sample rates, clock jitter, master clocks and all that kind of thing. And there's always the question of the console's group delay (latency) which, when overdubbing, may be enough to compromise the musicians' timing.

"All these things are areas of concern, and I had a lot of experience with this sort of thing in the early days of the Di‑An project at Trident. That was a digitally controlled, analogue console which we felt was a very happy marriage because you had the benefits of an analogue signal path combined with the benefits of digital control. Capturing a sound digitally, in other words recording onto a digital medium, has certain benefits, including reduced noise, the lack of any need for noise reduction, negligible wow and flutter, gapless punch in/out and so on.

"Once people could buy digital tape machines, there was pressure to provide a digital console to interface to it, but if you think about it, a digital console is an entirely different kettle of fish. What can digital give you when recording that an analogue console can't? It won't sound any better, and while you can easily get a bandwidth up to 40kHz with an analogue desk, you'd have real problems trying to do that digitally. The only advantage, other than direct interfacing with the tape machine, is in the area of control. What everybody wanted from day one was resettability — not lining up controls on a TV monitor and taking half an hour to do it, but a console that would automatically reset itself, preferably to SMPTE. Until we have a proper level of standardisation in the area of digital data formats, both for audio and control, I don't think that all‑digital desks are the way forward; anyone going down a particular digital path at this stage is being very brave."

Though by no means expensive considering what you get for your money, your consoles are priced such that only the top end of the project market and fully commercial facilities are likely to be able to justify buying them. However, I understand that you've also produced a rack‑mount equaliser based on your console EQ, and this is very attractively priced to appeal to the project market as well as the professionals.

"We had such a good response from console users about our equaliser that we decided to package it as a unit in its own right. The unit contains two channels of EQ and two of our mic preamps with switchable phantom powering, and we've fitted it with the new Neutrik XLR/stereo jack sockets so that it can be used with either type of connector. There are four bands of swept EQ, the same as on the consoles, and you can switch between mic and line inputs. The EQ sections all have bell responses and have a fixed Q providing a 6dB per octave roll‑off, which sounds very musical. Everything is self‑powered, in a 1U rack, and of course you can bypass the equaliser. It's almost like two channels of a desk without the aux sends, and it can be used in a number of applications. It's ideal for getting mic or line signals direct to tape without going via the mixer, and the mic inputs also work extremely well with electric guitar. The sounds range from a very warm guitar sound to really screaming overdrive when you crank up the input level. Because of this, the unit might also appeal to musicians as well as to recording engineers.

"In noise terms, it's the best microphone preamp we've ever used and is based around an SSM chip which comes very close to the theoretical limit on noise."

I still believe that there's a lot of life left in analogue consoles, and that they will be able to compete with digital consoles on both price and performance for some time to come.

I know you have another project under wraps at the moment, but as it will be unveiled at the APRS shortly after this issue of the magazine is on sale, can you tell us anything about it?

"We're launching a new console at the show, a smaller version of the 980, called the Series 900. It offers a lot of the facilities found on the 980, but scaled down. The input module is very similar, but you lose a couple of the auto‑mutes and the aux send system has been slightly simplified. We've left off things like the LED indicators on the routing but we've kept the second line inputs, and the monitor EQ is only 2‑band swept rather than 4‑band. And the faders are not conductive plastic as standard — that's available as an option. The price of the basic console should be around £15,000 for the 32‑channel version without patchbay. In terms of facilities, it still offers a great deal and we're very excited by it."

Why have you stuck to the split format when everyone else seems to have made the switch to in‑line designs?

"In‑line consoles are not the easiest to understand because you have this shared channel strip handling both the main signal path and the monitor. The reason they caught on is because they have a smaller footprint and are less expensive than split consoles. You do get a lot of inputs, but some of them have very few facilities, and on the early MCI desks developed by Dave Harrison, all you had on the monitoring side when you came to mix was, literally, level and pan.

"When we launched the TSM, we put a button on the monitor which routed it back to the groups to give our 32:24 console 56 useful inputs. With a split console, you don't have to compromise with things like sharing the EQ and aux sends between the main and monitor signal paths and you can do your whole mix from the monitor section if you want to, which avoids having to set up a new mix from scratch."

DI‑An — A Console Ahead Of Its Time?

The concept of assignable consoles with digital control surfaces is now pretty well understood and we have companies such as Euphonix, Tactile Technology, Yamaha and others working in that area. Do you feel that in retrospect, the Di‑An was a console ahead of its time?

"Definitely. We made a number of fundamental errors, the major one being that we couldn't bring it to the market in time. It was one of the earlier vapourware products. I still stand behind the concept 150%, and I still think there's nobody out there with a system to beat it for ergonomics. We said that if you were going to have assignability and total resettability, the only logical approach was to make it, effectively, a one‑module console; when you looked at that one module, it told you that you everything about the channel you were working on. You just had to hit one assign button and you knew exactly what that channel was doing.

"Of course you still have to retain separate faders for each of the channels because you're always working the faders, you want tactile feedback. When we did the Di‑An, young graduate engineers would come up to us and tell us we could do it on a PC, but then you'd lose the control.

"The initial reaction of people seeing it for the first time was 'My God, where are the knobs?', but after ten minutes or so, to a person, they all said what a wonderful interface it was and how easy it was to use."

Trident, Toft & T‑Rex

Malcolm Toft worked as a recording engineer with Trident Studios until around 1972 when he moved into mixing console design and manufacture. Although he's now more famous for his mixers than for his mixing, he is able to provide some amazing insights into the recording methods of the era. Bearing in mind the current interest in the '60s and early '70s sound, I asked Malcolm to explain how a typical session was set up.

"We would use something like a [Neumann] U67 just over the snare, an overhead mic which would also be a 67, and something like a KM54 over the toms and a D12 on the bass drum — front head removed and a blanket inside. We might use half a dozen mics on the kit; it was drums that we always had problems getting a sound with — we often spent five or six hours getting a drum sound. No matter what you did with EQ'ing and everything else, if the drummer wasn't laying the stick on the snare drum in the right way, it didn't matter what you did, it just wouldn't sound right.

"I remember one occasion when Clem Cattini came in and did a session using the house (Ludwig) kit in the morning and I used just a snare drum mic, an overhead mic and a bass drum mic. We had Herbie Flowers on bass, with just one mic in front of his amp, and it all sounded great. In the afternoon, another band came in and used exactly the same kit, and we spent six hours trying to get a drum sound with half a dozen mics. The tuning was the same, the mics were the same, but the drummer was used to playing live and couldn't play for the studio. And there's a great deal of difference in technique between playing for live and playing for a recording engineer. The difference between a good session musician and an average session musician very often wasn't musical ability but being able to produce the right sound.

"The guitar sound in those days was down to the playing; there was no special recording technique, just something like a Vox AC30 with a 67 stuck in front of it. One trick when recording an amplifier stack was to have one mic right up against the grille and another four or five feet away to get the ambience and sustain. You could only do that when overdubbing — when everything was playing together, you didn't have that luxury.

"The drums were set up in an alcove which was actually beneath the control room, and the only way we got separation was by a combination of mic technique and portable acoustic screens. There were no glass‑fronted drum booths or anything like that. We usually managed to maintain pretty good separation, though there was generally a bit of bass rumbling around, and we always had problems with other instruments leaking into the string section mics — especially brass. Bass was never DI'd in those days — we'd just stick a D202 six inches or so in front of the cabinet."

"Trident studios had dreadful acoustic problems — you could move from the front to the back of the control room and the bass response would change completely. But we recorded hit after hit after hit, and we didn't have nearfield monitors, we had big Tannoys in Lockwood cabinets. Because we all knew the studio, we produced mixes that sounded good elsewhere.

"I feel very fortunate to have been there at that time. When I took the job at Trident, none of us knew that it would become the studio that it did. I was the first engineer that Trident employed, and I got the job purely by chance after meeting them at the opening party. I didn't think then that it was my big chance; it was just a move up because they were 8‑track. Within nine months, Elton John — Reggie Dwight — came along as a total unknown and produced his first album with Gus Dudgeon. The producers who used the studio were mainly Gus and Tony Visconti. I worked largely with Tony, so I got to work with David Bowie and T‑Rex.

"When I was working with T‑Rex, it was in their acoustic era when Mark Bolan was playing with Steve Peregrine Took, doing all the hippy, Lord of the Rings stuff. We did the They Were Fair and Wore Stars in Their Hair, and Seers, Prophets and Sages albums, but Mark got frustrated because they weren't getting the commercial acclaim he wanted. I used to try to get Mark to play an electric guitar, but at first he didn't want to know. Then, in the early '70s, he went totally the other way, got hold of a Fender Strat and never looked back. Tony Visconti was very involved in forming him, and he's the only person I've ever worked with who I'd call a complete producer. He was a musician, he was interested in the technology, and he was interested in what the artist was doing.

"Of course you also got to work with producers who couldn't produce their way out of a paper bag — you'd have bands trying to perfect their third triple‑tracked harmony and you felt like saying what's the point, it's not going to make any difference because the song is no good. And these people would give you a lot harder time than Tony — if the song wasn't right, it was because the can level wasn't right or something; it was always the engineer's fault."