This month, Sam Inglis shows you how to improve your lyric writing by using fewer words to say more. This is the fourth article in a five‑part series.

In this series, I've been looking at some of the techniques poets use to analyse and write their material, and trying to show how they can help us understand what makes pop lyrics good or bad. Last month, I tackled metre and rhyme — phenomena that can make a verse, couplet, phrase or hook memorable simply because of the way it sounds when spoken or sung. This month, and in the next part of the series, it's time to consider the actual meaning of the words and phrases in song lyrics. In other words, supposing we know what we want to say in a song, how can we express ourselves in a way that is true to our feelings and best conveys what those feelings are?

The adage 'choose your words carefully' applies with special force to poetry and lyric writing. Not only is the correct choice of individual words essential in order to achieve the sonic effects described last month, but it also determines how well your lyrics express the meaning you want to convey. Compared to a piece of prose such as a short story, most poems and song lyrics contain very few lines, yet the lyrics of a song may have to do as much 'work' as an entire story. Indeed, as we saw in part two of this series, songs in the narrative mode actually do have to tell a story; and while the lyric and dramatic modes are less similar to most prose writing, they still have to convey a feeling or message.

Connotation & Denotation

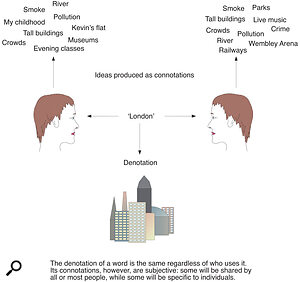

Figure 1. Connotation and denotation.

Figure 1. Connotation and denotation.

An average novel contains around 100,000 words, whereas an average pop lyric probably contains somewhere between one and two hundred words — about the length of the average novel's back‑cover blurb. How can a song lyric say anything at all significant in so few words? In order to see how this is possible, we need to identify the two different senses in which those words can be said to have meaning.

When we say that a word, phrase, or symbol 'means' something, this is usually understood as consisting of two separate components. One is what is called the denotation, or literal meaning, of that word or phrase — which we might think of as the actual thing or property to which the expression refers. Names, for instance, denote the person to whom they belong. Nouns such as 'table' denote things such as, well, tables. The situation with adjectives is slightly more confused, but we could say that adjectives such as 'yellow' or 'heavy' denote the quality of yellowness or heaviness. In general, the denotation of an expression is what we might call its 'dictionary' or 'objective' meaning.

The other component of meaning is known as connotation, and is usually understood as the set of associations that a word or phrase has. The literal meaning of the word 'spinster', for instance, is simply an unmarried woman who lives on her own: but to describe someone as a spinster is to imply far more about her life than this fact alone. If you described someone as a spinster, the person to whom you're talking would be likely to form far more beliefs about her than that she is an unmarried woman who lives on her own: the description might, for instance, call to mind the idea of a lonely, unhappy, or unfulfilled life, although nothing in the dictionary meaning of 'spinster' implies any such idea. To take another example, the word 'crypt' refers literally to an underground chamber beneath a church — but to most people a crypt is also a place associated with darkness, fear, and perhaps the supernatural. Referring to some place as a crypt rather than, say, a 'church cellar', or a 'room underneath a church' would allow you to bring to mind these creepy associations in your listeners without actually having to state them. (See Figure 1, left.)

While expressions may have several different dictionary meanings or denotations, each of these meanings is the same for everyone. The word 'table' denotes a flat surface supported on posts, and (in another meaning) columns of words or figures; and it does so regardless of who uses it. The connotations of a word or phrase, however, are subjective. Those born and raised in England, for instance, might associate the word 'summer' with rain and wind, while those who have lived their entire life in the Sahara Desert would be more likely to associate it with searing heat and drought. What connotations a word has for you will depend on innumerable factors — your childhood experiences, your background, your job, your education, your interests, your group of friends, the culture in which you live, and so on. Some words will have connotations that are peculiar to you only, or to just a few people, while most words have other connotations which are more universal. (Note that there is no absolute distinction between connotation and denotation, and when a word has a particular connotation that becomes universal enough, that can become part of its denotation.)

Connotation is what allows great depths and subtleties of meaning to be expressed in the few words that a song or poem permits. The art of choosing the right words in songwriting has a lot to do with considering not only their literal meaning, but also the connotations they have for you and for your listeners. For instance, suppose you were writing a song about a lonely single woman. You could simply describe this character as 'a woman living on her own': but you could convey a great deal more by describing her instead as 'a spinster', because for most people this term is much richer in connotation. Likewise, although the phrases 'the house where we live' and 'our home' have the same denotation, the word 'home' has all sorts of connotations that are not called to mind by the first phrase.

If you can make connotation do some of the work for you, rather than saying everything you have to say through literal statements, the results will be more subtle and artful, more concise, and often more memorable. As a very basic example, consider The Beatles' 'She's Leaving Home'. If we were to rewrite just the title phrase without using the word 'home' and its particular associations, how could we convey the same meaning? If we tried to express the ideas literally rather than through connotation, the result would probably be some horribly cumbersome line like 'She's leaving the house where she grew up with her parents' — and even this would still leave out some of the associations of 'home'.

<h3>Using Connotation</h3>

It is often through connotation that the words of a song exert most of their effect on the listener. So how can you ensure that you choose words that will have a sufficiently powerful effect? And just as importantly, how can you ensure that your words will have the right effect?

It can be a useful exercise to write down what it is you want to say in your lyric, locate the key words, and try to find some synonyms for them. These will usually have somewhat different connotations, which you may find more appropriate for your song. Think also about what ideas the expressions you've used in that description call to your mind, and try substituting those instead. Pairs of expressions often connote each other — to most people, for instance, mention of sunshine will call to mind blue sky, and talk of blue sky will call to mind sunshine. However, 'blue sky' may have other connotations that 'sunshine' doesn't, which may make it a richer expression to use in your song. It's also important to be sure that your chosen words aren't inadvertently triggering completely the wrong associations in your listeners, particularly if you're using unusual or opaque turns of phrase.

As I mentioned earlier, connotation is subjective: any connotations a word or phrase has are connotations for someone. Some expressions have connotations that are more or less universal, in that virtually anyone who hears them will form the associated idea. Others may be unique to one or two people, or to a group of people. When you're choosing words and phrases, then, it's important to think about who will be listening to the song. Don't assume automatically that just because a particular word or phrase has certain associations for you, it will necessarily have the same associations for other people. You want to be sure that most of your listeners will 'get' most of the connotations you want to put across, so think about what ideas those expressions call to your mind. Are those ideas connected in everyone's minds, or are you connecting them because of some unique experience that you've had in your childhood, which no‑one else is likely to have had? Is anyone apart from your girlfriend or boyfriend really going to understand the references you make when you write that tender love song to them?

There's nothing wrong with including some references which will only have a particular connotative meaning for a few people, but you will exclude many of your listeners if understanding the song depends on making these associations. While it's important that other people will share the associations that you have with the words you use, however, you need to make sure that you are using language in a fresh way, rather than lapsing into cliché. Moreover, it's often events in your personal experience that have made a big impression, that have a particular power to bring to mind other ideas or emotions, and that you want to write songs about! So how can you base songs on your personal experiences and associations without alienating any listeners who weren't themselves involved in your own personal history? A good way to write such a song can be to use connotation 'in reverse': trace out the associations that an important event, place, or thing has for you, and use the lyrics to explain why it has such power to evoke these ideas. If your song can make clear why this event can summon particular associations for you, there's a good chance it will have the power to move other people too.

The Beatles' 'Strawberry Fields' and 'Penny Lane', for instance, are clearly inspired by places that meant a lot to John Lennon and Paul McCartney in their childhoods. In each case, a simple reference to the place is clearly enough to bring back a whole slew of memories and ideas to the author of the song, and the lyrics are an attempt to place the listener in the position of the child forming these associations. There are many similar examples in pop music: another is Prince's 'Raspberry Beret'. The red hat of the title probably connotes nothing to most people, but to Prince it clearly has a lot of significance as a reminder of an old affair, and the song itself explains why it has this significance. It puts the listener in the position of understanding why an item of headgear has such power in the author's memory.

Figures Of Speech

'Under The Bridge', from the Red Hot Chili Peppers' Blood Sugar Sex Magik, and 'Dr. Robert', from the Beatles' Revolver, have drugs‑related connotations for their writers which might not be shared by the listener.

'Under The Bridge', from the Red Hot Chili Peppers' Blood Sugar Sex Magik, and 'Dr. Robert', from the Beatles' Revolver, have drugs‑related connotations for their writers which might not be shared by the listener.

The use of a detail to connote, or to represent a 'bigger picture', brings me on to the second half of this month's instalment. Thus far, we've only looked at how considerations of connotation might influence a choice between different literal descriptions of the same thing: 'our home' might be preferable to 'the house where we live', because it has greater power to call to mind other ideas, but in both cases the expression's literal meaning is crucial. We want to talk about the building we inhabit, and both expressions fit the bill thanks to their literal meaning. In this case their connotations are, lyrically speaking, the icing on the cake.

Connotation really comes into its own, however, when words are used non‑literally, to create figures of speech — such as 'the icing on the cake'. A figure of speech is any phrase or word which is used to convey a primary meaning that is not its literal meaning. The dictionary meaning of the string of words that make up a figure of speech is secondary to its connotative importance, and may even be nonsensical or obviously untrue. When we employ a figure of speech, however, we bring a new and different set of connotations to the actual subject we're attempting to describe. In this way, we can describe real things or events in ways that literal language could not allow.

Almost all writing — prose and verse — uses figures of speech. However, they are particularly important for verse (and hence lyrics) because of their power to encapsulate meanings into far fewer words than would be needed to convey the same thing through literal description, and also because they can be used to capture nuances of meaning that cannot be said directly.

Using a figure of speech rather than a literal description can make lyrics seem more interesting. The great majority of pop songs tackle the same few subjects — mostly relationships, whether good or bad. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it does mean that many of the obvious lyrical approaches to these subjects have been taken many times before. How can you come up with a new way to talk about love? Well, one way to do it is to find a new figure of speech. Some of the most memorable lyrics in pop history are those which say nothing new, but say it in a way that has never been used before.

Figurative speech also sometimes has an obscuring effect, making the listener work to find out what a lyric means. This can, as we shall see, be annoying and self–defeating when it's overdone or done inappropriately, but it can also have a positive effect. If you draw the listener into having to think about what your lyrics mean, you can hook them more deeply than you could by merely telling them plainly what you want to say.

Figures of speech are so common in ordinary conversation and writing that we usually forget that we are using words in a non‑literal sense. Probably the most important figures of speech, both in ordinary conversation and in verse, are metonymy, metaphor and simile. The latter two will have to wait until next month, but I'll close this instalment with an introduction to metonymy.

Metonymy

Metonymy is probably the figure of speech we use most of all, but it is also the one of which we are least aware. When we refer to something using literal language, for instance in a phrase such as 'the city of London', we use words that denote that thing directly; and these words also have connotations, which are implied but not stated. 'The city of London' might, for instance, call to mind ideas of noise, crowds, smoke, tall buildings, red buses, and so forth.

To refer to something using a metonym is to take one of these connotations — an attribute or idea that is usually associated with the thing you're talking about — and to use that, rather than the name or literal description, to refer to it. Thus, for instance, the phrase 'the big smoke' is sometimes used to refer to London, since smoke is so widely associated with London. London is smoky, but when we say 'the big smoke', we're not talking only about the smoke: we're talking about the city that produces it. (See Figure 2, above.) Similarly, when the phrase 'the Crown' is used to mean the Queen, it's not intended to refer only to the Queen's headgear, but to the whole person. And if someone says 'I've got a nice motor', they are usually talking about their car as a whole, rather than just the bit under the bonnet.

So why use these substitute phrases, rather than simply saying 'London', 'the Queen', or 'a car'? One reason is that metonymy provides a neat way of not only referring to something, but also of emphasising a characteristic or making a point about it at the same time. Saying 'I've got a nice motor' carries most of the meaning of 'I've got a nice car', but it also suggests that what's good about your car is its engine. This, in turn, brings to mind connotations of speed, power, noise and so forth, which are not suggested to most people by 'a nice car'. In other words, the metonym emphasises and states plainly something that is merely a connotation of 'a nice car' — the idea that a good car has a powerful engine — and brings its own set of connotations along too. A second reason is that, like all figures of speech, metonymy allows us to say things in original, interesting and poetic ways, even though they might normally be mundane or obvious.

Perhaps the main reason why metonymy is so important in songwriting, however, is that a simple metonymical phrase can often capture a complex nuance of meaning that could not be expressed literally, or would require paragraphs of description to do so. 'The big smoke' is obviously a substitute for 'the city of London': but other metonymical phrases do not have neat literal equivalents, and they thus allow us to say economically what could not briefly be said in literal terms. It is, for example, virtually impossible to sum up an entire lifestyle using only literal descriptions — but it can be done by stating a few well‑chosen details...

Metonymy In Pop Songs

Figure 2. Connotation and denotation via metonymy.

Figure 2. Connotation and denotation via metonymy.

I mentioned the unusual switching between poetic modes that takes place in Pulp's 'Common People' in the second instalment of this series. This song also contains some excellent examples of metonymy. Take, for instance, the second line, 'She studied sculpture at St. Martin's College'. The literal meaning of this sentence is mundane. Its primary meaning, and its lyrical effectiveness, lies in its associations — Jarvis Cocker clearly associates studying sculpture at St. Martin's College with being a privileged, expensively educated but dim Sloane. Thanks to metonymy, a single line tells us everything we need to know about this person's character, in a way that's never, ever been used in another song.

Later in the song, Jarvis Cocker invites the girl in question to 'Rent a flat above a shop / Cut your hair and get a job / Smoke some fags and play some pool / Pretend you never went to school'. The message is that, even if she lives her life exactly as the common people do, she'll never be one of them — but rather than trying to provide a complete description of the life that common people lead, Cocker evokes that life metonymically, through the use of a few well–chosen details. You don't actually have to play pool to be a 'common person', but it's the sort of thing that common people do, an activity associated with a particular lifestyle. The pool‑playing is not important in its own right, but because it represents a way of life; and by mentioning three or four well‑chosen details, the verse manages to sum up an entire lifestyle.

The Beatles' 'When I'm 64' provides further examples of the kind of metonymy wherein details are used to evoke an entire way of life. Paul McCartney describes the life of an old‑fashioned retired couple through snapshots — the cottage on the Isle of Wight, the grandchildren called Vera, Chuck and Dave, and so forth. Again, these details are unimportant in themselves: their function is to represent a broader way of life.

Like other figures of speech, metonymy can be used on a variety of different scales. For instance, a single line may contain two or three individual and unrelated figures of speech; but conversely, entire songs can be created from a single figure. To return to Jarvis Cocker's lyrics, the album Different Class contains a particularly ambitious example of metonymy in the shape of 'Live Bed Show'. In fact, the major lyrical feature of this song is a metonym: the bed of the title, which is used to describe its owners' failing relationship. In the beginning: 'It didn't get much rest at first / the headboard banging in the night / the neighbours didn't dare complain' — yet seven years on, 'There's no need to complain / 'cause it never makes a sound'. Taken literally, the lines are just about a bed, but their primary meaning is metonymical: to suggest the state of the owners' sex life.

Another song based around a metonym is 'The Green, Green Grass Of Home', recorded by Johnny Cash and by Tom Jones, among many others. Taken literally, the idea of touching some grass would hardly be worth writing a song about, but the green, green foliage in question is a metonym. When the condemned man thinks of the home life he'll never see again, he thinks about specific details. It's not the actual act of touching the grass that's important, but its wider symbolism and its associations.

Next Issue

I hope that this instalment has demonstrated some of the lyrical achievements that can be made using the power of words to call to mind ideas beyond their literal meanings. Metonymy in itself is a powerful tool, but it is only one of several commonly used figures of speech. Next month, I'll be looking at some of the others, and how they are used in pop lyrics.

Re‑arrange These Words

Although I've focused on poetic techniques that are applicable to songwriting in this series, there are obvious differences between song lyrics and poetry. Rather than standing alone on the page or as speech, lyrics have to complement the musical arrangement and melody to which they're put. The words are all that there is to a poem, and they thus have to carry the emotive, dramatic or narrative content of that poem on their own. A song, however, derives its content from the combination of music and words, and the significance of a lyric can be highly dependent on its musical setting. Take nursery rhymes sung by small children, for instance: unaccompanied, they convey a charming and happy sense of childhood. Put some creepy dissonant violins behind them, however, and you have the staple of a hundred horror‑film soundtracks.

Whether you write lyrics and music at the same time or not, then, it can be important to consider how lyrics relate to their musical setting. To take a simple example, in general minor keys and descending melodies tend to sound melancholy, whereas major keys and ascending melodies have a positive aspect. These associations are often used to reinforce the affectiveness or a sad lyric, or to make a positive lyric into a more uplifting song. However, you can also employ the interdependence of music and words in more sophisticated ways. A melancholy musical setting could be used to undermine an apparently cheerful or positive lyric, giving it an altogether different meaning. Radiohead's 'Fitter Happier', for instance, consists of a list of fragmentary phrases describing an ostensibly happy person, and it is left to the delivery and the bleak musical background to illustrate that these phrases are merely empty clichés. (I suppose it makes a change from the bleak music with bleak lyrics that makes up the rest of their output...)

Similarly, dissonant or suspended chords and awkward rhythms can convey tension and conflict, while smooth rhythms and harmonious chord patterns can suggest harmony in a wider sense. Both techniques are beautifully employed on 'Easter Theatre' from XTC's Apple Venus Volume 1: the verses describe, both musically and lyrically, the apparently disorganised, frantic activity of nature in Spring, while the chorus introduces the idea that all of this is somehow arranged and organised by Easter.

Look, No Connotation!

Freda Payne's 'Band Of Gold' uses a neat lyrical device whereby the absence of connotation is used to make a point. 'Now that you're gone,' she sings, 'All that's left is a band of gold.' By deliberately using the stilted, literal phrase 'band of gold' rather than 'wedding ring', the song makes the point that the usual ideas we associate with wedding rings are no longer applicable when the marriage is over. All that a wedding ring without a marriage amounts to is a band of gold.