Liam Watson went against the grain to build a studio with the retro sound he loved — and now that sound is back in fashion, he's had a number one album with the White Stripes.

In the Spring of 2003, it seemed that every music magazine had the White Stripes on the cover, and the duo of Jack and Meg White had truly arrived in the mainstream. The group's fourth album of stripped-down blues, Elephant, went to number one in the UK charts and sold a lot of copies around the world. Unusually, the media was remarking on the way the music had been recorded as much as the music itself, with reviews claiming that London's Toe Rag Studios contained not a single piece of equipment manufactured after 1963, or had banned digital technology in favour of a retro-purist approach.

There's a certain amount of romanticised exaggeration in these claims. For one thing, Toe Rag has its own web site — surely not the sort of thing that an outfit of die-hard analogue nostalgics would want anything to do with — and while the site is designed to look like an old audio catalogue, it clearly lists plenty of modern equipment in use at the studio, right up to a CD recorder and DAT machine. However, the main focus of the studio's equipment collection is on classic analogue hardware — microphones including Neumann, Reslo and STC models, backline amps by Vox and Selmer, vintage Calrec and EMI mixing desks and a top-quality assortment of multitrack tape machines. Outboard processing consists of some antique EQ, compression and reverb units, with monitoring done on 15-inch Tannoy Red drivers in Lockwood cabinets, powered by Quad II amps.

The Elephant Man

Liam Watson, the studio's founder, resident producer and chief engineer is clearly unfazed by the success of Elephant: he still answers his own phone, and is friendly, direct, and obviously passionate about his way of recording music. Like so many people, he got started in recording by playing in a band and working on his own material at home. But when he had the idea to open a purpose-built studio in the early '90s, it was a bold decision to specialise in vintage analogue recording just as other studios were embracing DAT and digital reel-to-reel machines, and were about to see the launch of ADAT. Looking back now, it seems obvious that there was a niche market in retro sound recording that was just waiting to be created.

Liam Watson, the studio's founder, resident producer and chief engineer is clearly unfazed by the success of Elephant: he still answers his own phone, and is friendly, direct, and obviously passionate about his way of recording music. Like so many people, he got started in recording by playing in a band and working on his own material at home. But when he had the idea to open a purpose-built studio in the early '90s, it was a bold decision to specialise in vintage analogue recording just as other studios were embracing DAT and digital reel-to-reel machines, and were about to see the launch of ADAT. Looking back now, it seems obvious that there was a niche market in retro sound recording that was just waiting to be created.

"We were setting up the studio in 1991," explains Watson. "My favourite records are pretty old records really, done in the '50s and '60s, and at that time my original business partner was willing to invest a little bit of money in me starting a studio. I said that what I'd really like to do, because I'd been in bands, would be to make a studio like an old studio was, with all old analogue stuff. That was basically because of my love of those records, and that kind of sound wasn't really being achieved. At that time I didn't know a great deal about studios, but my limited experience was that they didn't sound very good and I didn't know why.

"The other reason was that if I was going to invest a lot of time and money into making a studio at that time, I didn't want to build another bog-standard cheapo 24-track studio. One reason was that I don't like those studios, and another reason was that at the time there were loads of those studios opening up all the time and then closing down every week because they didn't really offer anything unique. So as well as my love, I thought it would have been a bit of an experiment, but I had a gut feeling that it would be something that would be appreciated by certain people."

The main mixer at Toe Rag is this 18-input Calrec M-series.Photo: Richard Ecclestone

The main mixer at Toe Rag is this 18-input Calrec M-series.Photo: Richard Ecclestone

Of course, Toe Rag Studios didn't open with full racks of vintage equipment, and has built up its collection of analogue hardware over the past 12 years. "When we initially opened, we had nothing really. We had remnants of what I'd been using in my house. We started off with a half-inch eight-track machine, and we had a really old mid-'60s customised one-off console that had come from an old studio. It had been built by an ex-BBC engineer. So we started off with those two things as the main thing, mastering down onto a Revox, and just developed from there, picking things up as we went along."

Perhaps it was inevitable that a rush to digital recording would eventually create a demand for the best of the equipment left behind, as the pendulum of fashion swung back. Investing in recording equipment from the 'golden age' of analogue turned out to be a shrewd financial move, since the old equipment had become relatively cheap by that time. "That desk didn't cost very much, and the half-inch eight-track wasn't very expensive. Then we bought an old Neumann valve microphone which was fairly expensive, but we did have quite a big collection of amps and guitars and stuff as well."

Ball And Biscuit

The STC 4021 'ball and biscuit' microphone.Photo: Richard EcclestoneThe White Stripes' song 'Ball And Biscuit' appears on the Elephant album, and Toe Rag Studios just happens to list an STC 4021 microphone among its equipment — known as the 'ball and biscuit' due to its curious shape. A moving-coil omnidirectional mic used at the BBC and originally produced in the 1930s, the 4021 was allegedly copied from the very similar-looking Western Electric 630.

The STC 4021 'ball and biscuit' microphone.Photo: Richard EcclestoneThe White Stripes' song 'Ball And Biscuit' appears on the Elephant album, and Toe Rag Studios just happens to list an STC 4021 microphone among its equipment — known as the 'ball and biscuit' due to its curious shape. A moving-coil omnidirectional mic used at the BBC and originally produced in the 1930s, the 4021 was allegedly copied from the very similar-looking Western Electric 630.

Roger Beckwith has created a web site detailing the equipment used at BBC Radio across the whole analogue era, including these early microphones, mixing desks, tape machines and turntables, with studio layouts and diagrams. Since so much classic British audio hardware originated from (or was used by) BBC engineers, the site is a good place to start if you are interested in vintage analogue gear.

Studer Studies

Despite the age of some of the mission-critical equipment at Toe Rag, Watson doesn't find he needs to keep two of everything in order to safeguard against breakdown in the middle of a recording session. He finds his tape machines to be dependable, even though they are probably older than most of the musicians recording on them. "I'm using the Studer tape machines now, and I find them to be very reliable. There are things that go wrong with them, but they're usually fairly easy to fix. I've got quite a lot of spares, and it's very rare that the machine will go so wrong that you have to stop a session. But if there is something, there's usually a way around it, and then I can pretty much tweak it myself. It's total pro gear — some people consider a Studer machine to be the Rolls Royce of tape machines. I always remember people telling me that when we first started — 'Oh, you need to get a Studer." I find them really good, and I have a one-inch eight-track, a two-inch 16-track, and a two-track quarter-inch.

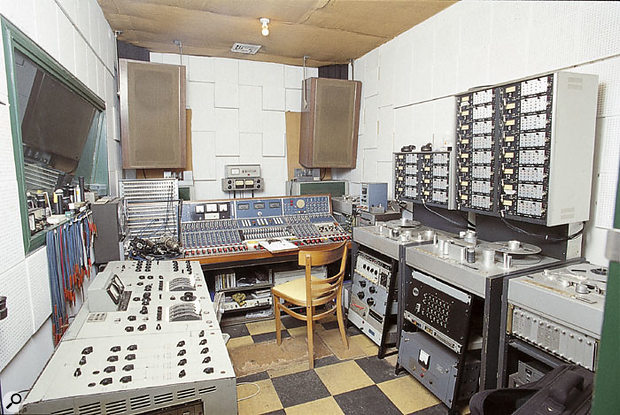

The Toe Rag control room. On the right are Liam Watson's three Studer tape recorders, with the Lockwood speakers on the rear wall. Photo: Richard Ecclestone

The Toe Rag control room. On the right are Liam Watson's three Studer tape recorders, with the Lockwood speakers on the rear wall. Photo: Richard Ecclestone

"The original Studer A80 was a two-track quarter-inch machine and it came out in about '66, but they were making them until some time in the '80s. By the time it stopped they were up to a Mark V or a Mark VI. Our eight-track and our 16-track are Mark IIs, so that's sometime in the early '70s. The quarter-inch we've got is called an RC, it has the electronics from the mid '60s, but that's actually a machine that came out in a very limited edition in 1979. What happened is that by '79, some of the engineers at the BBC or EMI I think, who all used A80s, were saying 'Hold on a minute — we love the deck of the A80, but we actually prefer the audio from the B62-series tape machines. Couldn't you combine the two?' So they did, and the RC is the combination of the two machines."

The live room at Toe Rag.Photo: Richard EcclestoneSo even in the 1970s, people were already saying that studio hardware wasn't as good as it used to be. Is analogue recording just about nostalgia? "People prefer certain machines. Some people don't even like Studer tape machines and swear by other makes. I think, personally, once you get to a certain level of competence and sound quality, it's very much a personal thing. There's not that much difference, really."

The live room at Toe Rag.Photo: Richard EcclestoneSo even in the 1970s, people were already saying that studio hardware wasn't as good as it used to be. Is analogue recording just about nostalgia? "People prefer certain machines. Some people don't even like Studer tape machines and swear by other makes. I think, personally, once you get to a certain level of competence and sound quality, it's very much a personal thing. There's not that much difference, really."

Having good suppliers is all important, since you can't run into a high-street music shop and buy extra reels of tape for an urgent session. Fortunately, London does still have places which can supply most of the needs of all-analogue studios. "You've got Studiospares, you've got Protape. You can walk in off the street and buy tape fairly easily. I find the two-inch is usually the easiest to get. The one-inch and the quarter-inch aren't such normal formats — there's not many people using one-inch tape, and a lot of people use half-inch more than quarter-inch now."

But to use vintage equipment, is there a set of arcane skills which you need to acquire in order to get the most out of it? "There definitely is. I know what to do, so for me I just do it. There are certain things you have to be aware of, that other people who might come in and try and use the studio might not be aware of. Things like level to tape, not overloading stuff. I know what I'm doing, but I don't know any different.

Photo: Richard Ecclestone"If you're using a digital recording medium you plug it in, it's ready to go. With an analogue tape machine like a Studer... I'm actually in the middle of realigning the 16-track. You've got to get the bloody manual out, then the test tape, then you've got to have your voltmeter — it's hands-on. Once it's aligned it's good, but you can't just plug it in and go, because you don't know what you're doing. So if someone gets an analogue machine, if it sounds awful it's probably something wrong in the alignment. Then you've got to know how to do the alignment. If you don't know it you've got to get someone else to do it, and if you don't know anything about it you've got to keep your fingers crossed that they know what they're doing, because a lot of people claim they do, and they don't."

Photo: Richard Ecclestone"If you're using a digital recording medium you plug it in, it's ready to go. With an analogue tape machine like a Studer... I'm actually in the middle of realigning the 16-track. You've got to get the bloody manual out, then the test tape, then you've got to have your voltmeter — it's hands-on. Once it's aligned it's good, but you can't just plug it in and go, because you don't know what you're doing. So if someone gets an analogue machine, if it sounds awful it's probably something wrong in the alignment. Then you've got to know how to do the alignment. If you don't know it you've got to get someone else to do it, and if you don't know anything about it you've got to keep your fingers crossed that they know what they're doing, because a lot of people claim they do, and they don't."

If The Feel's Right

Does the all-analogue approach mean Watson has work in a way which is more focused on performance, because he can't edit endlessly or drop in fixes like you can in a computer-based studio? "You can go back and edit and edit and edit, and you can drop in to a certain extent, but you're basically working on a performance. If you do have a real great performance and there's one bum note, it's like 'That's really great, it's taken us f***ing hours, let's see if we can just patch in this bit.' You can do a little bit of that, but if you can not do that, it's much better. You're looking for performances. It's not like now, when you can do some half-arsed crap, and then correct it. People spend hours correcting the drums — we don't do anything like that. You know when the feel's right, and if the feel isn't right, then you just do it again."

Toe Rag's vintage equipment selection extends to guitar amps. Photo: Richard EcclestoneDoes this mean sessions tend to be short, with musicians in and out of the Toe Rag doors at a rapid pace? "I'll take as long as is needed, and no longer. I don't like fussing around when it's unnecessary because it just kills the vibe. I am prepared to sit there all day, doing one particular thing that's very boring if that's what it takes, but not for the sake of it. It's usually fairly quick. We have quite a lot of people coming in and out — there's quite a lot of sessions going on."

Toe Rag's vintage equipment selection extends to guitar amps. Photo: Richard EcclestoneDoes this mean sessions tend to be short, with musicians in and out of the Toe Rag doors at a rapid pace? "I'll take as long as is needed, and no longer. I don't like fussing around when it's unnecessary because it just kills the vibe. I am prepared to sit there all day, doing one particular thing that's very boring if that's what it takes, but not for the sake of it. It's usually fairly quick. We have quite a lot of people coming in and out — there's quite a lot of sessions going on."

Watson thinks of himself as a producer rather than an engineer. This is hardly suprising, given that the way he records music with vintage hardware will inevitably produce a distinctive sound. "I totally consider myself a producer. I don't need an engineer, because I know what I need to do. I wouldn't engineer for somebody — there's no way I would be an engineer." He has no time for people who claim to record music without 'producing' the sound, hiding behind the mantle of a mere engineer. "That's all a bit crap as far as I'm concerned. Take the plunge! When I make a record with somebody, it will usually end up sounding a certain way, because of the things I do. And if that isn't record production, I don't know what is. No-one tells me what to do, but I will ask them what they want, if they have any ideas or specific things. Tell me what you'd like this to be like, what you're trying to achieve, and I'll say 'OK, if you want to do that we need to do this, this and this.' I will do what's needed to be done, but what I hate is when people say 'Maybe we need to do this.' Someone's just said 'Can I compress this?', for instance. Why do you want to compress it?"

Fiercely independent, Watson is unlikely ever to work with someone from the record label standing over his shoulder. "I wouldn't do that because I know more than these people anyway. As far as I'm concerned, I work with record companies, as in they pay me, and I do the job. Of course I send them the monitor mixes when we finish an album, and say 'How about this, or that?' I like people to tell me what they think about stuff when I need to know — but not before. I don't want to have a committee of people here when I'm mixing a record; it'll just be me and the artist, or perhaps just me."

Analogue Elitism

Despite being surrounded by vintage equipment, Watson is pragmatic and isn't opposed on principle to having a computer in the studio. "I'm not opposed to anything. If something sounds good, it sounds good and as far as I'm concerned, I don't care what it is. If it does the job, it does the job, and that's all I care about." He isn't adverse to using computer simulations of old equipment if the session requires it, either. "One time somebody bought a computer system in because they wanted to have the sound of a Mellotron, and we couldn't get a real Mellotron. It was OK, it was all right."

Now that certain equipment is very highly valued because it offers the so-called 'analogue sound', the potential exists for vintage recording to become elitist, and to actually cost more to set up than a modern computer-based studio. But if there's a Toe Rag philosophy, it's about just trusting your ears, not analogue snobbery. "I really hate that, and I completely get away from that. In fact, there are certain things that people pay a lot of money for, and it's very snobby — like you've got to have a Fairchild limiter or a Pultec EQ, or all UREI compressors. None of that stuff is particularly good, I don't think. I don't have any of it and I never will, because I hate that whole bullshit 'Ooh, you can't do that, you've got to use this.' It's bollocks, y'know? People can make great records in their bedroom on a computer, and they make better records than some rich rock star who's just bought an EMI desk and a load of Fairchild limiters.

"It doesn't really matter what you use as long as it does the job. I don't want a piece of equipment that doesn't sound good. If I have a tape recorder, for instance, I want it to sound like what I'm giving to it from the desk. And when I'm listening to the microphone through the desk, it must sound good."

The Past Masters

Watson's influences among producers are perhaps obvious, given his love of old records and the equipment that made them. "I've always liked the British approach to making records. I like a lot of the stuff that was done at EMI Studios, all the classic Beatles stuff, just the mid-'60s beat kind of thing, and various different producers — Joe Meek is probably my hero, in a way. When his records are good, they're great. He did so much stuff, and he really did a good job. Unfortunately, some of his stuff is pretty lame, but it's not because of him. Some of the songs were bloody awful, but when it's a good song it's usually a pretty good recording."

The vintage EMI REDD 17 valve desk was originally from Abbey Road.Photo: Richard EcclestoneMeek is best remembered for his work from the pre-Beatles era of British groups, but Watson points out: "He was going all the way through that. I quite like the later stuff just a couple of years before he died, when he was going in a really good direction I thought." Joe Meek not only influenced Watson through the records he made, but with his choice of equipment too. While the contemporary brand of studio hardware with the same name isn't much like the equipment actually used in the Holloway Road studio where Meek worked, lived and died, Watson seems to have researched Meek's setup in detail.

The vintage EMI REDD 17 valve desk was originally from Abbey Road.Photo: Richard EcclestoneMeek is best remembered for his work from the pre-Beatles era of British groups, but Watson points out: "He was going all the way through that. I quite like the later stuff just a couple of years before he died, when he was going in a really good direction I thought." Joe Meek not only influenced Watson through the records he made, but with his choice of equipment too. While the contemporary brand of studio hardware with the same name isn't much like the equipment actually used in the Holloway Road studio where Meek worked, lived and died, Watson seems to have researched Meek's setup in detail.

"He made himself a little panel mixer and a few bits, but he didn't make that much. He built a compressor, but from about 1963 onwards I think it was mainly off-the-shelf stuff that he probably modified. I've heard records he's done, I know the equipment he had, and he must have modified that kit because those compressors don't sound like that. It was all about the musicianship on those records — he ended up with some pretty extreme sounds, but he couldn't have got them if he didn't have the musicians there to do the job in the first place. He had the top guys playing for him."

Don't Lose Your Way

The success of Elephant means that Toe Rag has a long list of people knocking on the door, so Watson can afford to be choosy about new projects. It can't hurt your standing with clients to have produced a number one album, but he's never been keen to take direction — even before he was well known. "No one's going to tell me what to do, because I won't work with them! I only want to work on stuff that I'm going to enjoy. I enjoy working with Holly Golightly quite a lot, Billy Childish I've worked with quite a lot over the years, and still have fun working with him."

Is there a secret to recording the Toe Rag way? "Do as little as possible. If it sounds good, it is good, so leave it alone. If it sounds crappy, find out why it sounds crappy — I'm not talking about your recording equipment. If something sounds crappy like a guitar, is it the guitar amp? Go in and listen to the guitar amp, go and check it. Just don't do anything — you don't need to f**k around with things on a mixing desk in order to make it sound good.

"There is another side of things altogether if you want to get experimental — if you're making an avant-garde record, that's different. I'm just talking about recording rock & roll — a band. You don't need to f**k around with stuff because if it sounds good in the room, if you're using the right microphones in the right positions it should sound good in the control room as well. The less you do, usually the better it sounds. Go with your gut instinct — if it sounds good, don't start worrying about 'Oh, but what if it sounded...' Resist those temptations to suddenly switch the EQ knob on and start f**king around with it, because you'll lose your way. That's what I think, anyway."

Toe Rag's web site is at www.toeragstudios.com.