Pete Phillips (left) and Bob Prance.

Pete Phillips (left) and Bob Prance.

Bob Prance and Pete Phillips

Best mates Bob Prance and Pete Phillips have been musical collaborators for over 20 years, ever since they met at school in their home town of Liverpool. Remarkably, their friendship and working relationship has remained intact, despite them both spending many years working in the Middle East in different facets of the oil industry. Now the duo live just a stone's throw from one another in South London, where Bob has set up a cosy home studio in his attic. The space is used partly for Bob's own ambient music, but also for Bob and Pete's collaborations under the name of 'A Story At Bedtime Productions'.

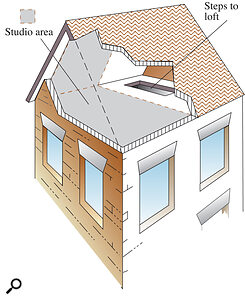

One half of the attic has been dedicated to the storing of miscellaneous gigging equipment and dust‑covered junk, which is surely best left undiscovered. The other half is the studio area, office and creative den. "I've been here eight years," explains Bob. "Before that I used to live in shared apartment in a block of flats. I could only get the recording gear out when everyone had gone to work, so I was desperate to get out. Sometimes I come up here and don't turn anything on. It's like going to church or something. This is also our office, so if we're not recording we're writing or emailing various people.

"The loft space was a paint store when I moved here, so I emptied it and boarded the floor with one‑inch fibreboard. The area was already partitioned, with loft insulation, and the wood panelling was already here. Then I just put carpets down. It has gradually filled with more and more stuff, and now something will have to go before I get anything new. It's just right, though, because I can spin round and reach everything from my seat. I've done stuff in big studios where you get exhausted just walking across the room. That just seems impersonal and I'm a bit wary of it."

The most ambitious project Pete and Bob have produced in the attic to date is a humorous radio play called The Astonishing Adventures of Mac Rodgers. The story combines sound effects and music with a narrative written and spoken by Pete. "Mac Rodgers is a demo for a larger project," explains Pete, "I'm rewriting the scripts for a full radio production which will have 18 episodes. We want it to have loads of characters rather than just a narrator, so it's not just a guy saying 'Mac did this and that.'" Seeking professional feedback, Bob sent a Mac Rodgers recording to Sound On Sound's John Harris for review in Demo Doctor. John was so impressed with the recording, he awarded it 'Top Tape' in March 2001. The project was recorded primarily using Bob's Akai CD3000 sampler, Pentium II PC333MHz/64Mb, Event Gina Soundcard, and Syntrillium Cool Edit and Sonic Foundry Sound Forge software, all of which made it possible for the pair to do the complicated edits required to combine sound effects, music and dialogue.

The idea for Mac Rodgers first occurred to Pete while he was still at school and, according to Bob, the first Rodgers recordings date back to 1976! Of course, back then Bob's computer setup was no more than a glint in a software developer's eye, so Pete and Bob had to make use of use of whatever equipment they could lay their hands on. Bob explains how they got started: "Me and Pete joined a school band where he was the drummer and I was the bass player. That led us to start producing radio stuff using just a ghetto blaster and a record player next to it. Pete would do all the narration and I'd put sound effect and horror records on and do the noises and bangs for it. We kept on playing in bands but we realised that this was a lot more fun. It made us laugh. He sparked me off, I sparked him off, and that was the chemistry."

Pete continues: "The band just sounded like kids playing music, but the radio stuff had something about it and it wasn't so derivative. We managed to get something played on MAR, which was Merseyland Alternative Radio — a pirate station — and people were ringing and writing in for our tape, so we knew we were on to something."

The Future Now

The Tascam 38 8‑track still finds its place alongside the computers and software in the studio.

The Tascam 38 8‑track still finds its place alongside the computers and software in the studio.

Encouraged by the positive feedback, Pete and Bob wanted to make their home recordings into something which sounded more professional, but they soon found that the high quality of production they aspired to was not achievable with the home recording equipment of the time. "Over the years, Mac Rodgers was put on the back burner," explains Bob. "We've just waited for the technology to be invented. We knew it would come along one day." Pete continues. "Twenty years ago it was too complex technically for us to do. We wanted some sound effects sequences to go on for 30 seconds and have 20 effects edited in. But once Bob got all his PC equipment, and particularly Sound Forge and Cool Edit, we could put 20 edits into a 10‑second space. Cool Edit allows you to take a piece of dialogue that says 'Mac... stood... alone...' and put a sound effect in between each word — and tailor the volume of the sound effects to what you want. We would have had to be millionaires to do that before. The years we've waited to re‑record these episodes of Mac Rodgers!"

Unable to start recording Mac Rodgers, Bob and Pete set about earning a living. Bob, in particular, wanted to invest in some studio gear, so he began looking at ways of earning large sums of money quickly. On the advice of a friend, Bob and Pete embarked on an adventure to the Middle East, in search of the easy money which they intended to acquire by entertaining well‑heeled oil magnates.

"Our intention was to play music in the hotels, " explains Pete, "so when we arrived we got a gig in the cocktail lounge of the Sheraton Hotel. We started playing Zappa and Zeppelin covers, but very suddenly we realised that the cocktail lounge at the Sheraton didn't like Frank Zappa!"

"We got pissed, they threw us out, and that was the end of that," laughs Bob.

Building The Studio

Fortunately, Pete and Bob managed to get work on the oil‑rigs, and were trained by an Ame rican oil company as mechanical engineers. The subsequent oil‑rig job which Bob found himself doing for the next five years paid for many expensive items of recording gear. "In 1982, Studiomaster released a four‑track cassette recorder." says Bob. "It had full four‑band EQ with parametric mid, inserts, the lot, and was very professional. That cost me more than everything I've got now. I just stuck with that for years, then in about 1989 I noticed Sound On Sound. But I couldn't understand a word of it, and I realised that I'd lost track of what was going on in recording. I was asking 'What is MIDI? What is a sampler?' It was only through reading those SOS reviews over and over again that it started to make sense to me.

"I read that I could plug keyboards into the computer and make sequenced loops, so I got an Atari Mega ST2. I still reckon the Atari was the best computer ever, because MIDI is built in, so you have no hassle, no cards, and hardly any crashes. And it was dead cheap. I bought that, along with a workstation keyboard and a four‑track. I tried to sync the four‑track to the Atari using a JL Cooper PPS100 SMPTE box, but it wouldn't work with Dolby and the four‑track automatically put Dolby C on! So then I bought the Tascam 38 eight‑track half‑inch. It has no noise reduction, but it's never needed it. I've done a whole album with it, and I didn't really notice much difference when I went digital.

"For that setup I had the Atari running in sync with the tape, then I'd make marker points in Cubase where things like a chorus came in. Those points signalled where to drop in and record onto the Tascam. I w ould have a sample rigged up ready to trigger from my keyboard. Sometimes I'd get a SMPTE delay, so I had to rewind to the beginning of the song every time and for every sample, to make sure it locked up properly; it had to be spot on. If I was doing something that was 20 minutes long I still had to go all the way back to the beginning!"

Up to that point Bob was using his equipment for non‑Mac Rodgers projects. Pete had been forging a successful musical career as a member of a band in Cyprus, while Bob was touring his own group in the UK and producing his own music. Eventually, both Bob and Pete ended up moving to London, by which time the affordability of technology meant that re‑recording the Mac Rodgers ideas was a possibility.

Bob's next purchase was an Apple Mac LC, which he bought for audio as well as sequencing, but he found that the machine wasn't up to the job. That experience was enough to put Bob off the idea of using a computer for audio until he bought a more powerful PC in 1998. "I went to Turnkey and got this PC built for mastering. I've read so many reviews saying PCs are not up to the job, but I think they can be OK if you get one from a music dealer. I've got three or four mates who bought systems from Dixons and got nothing but trouble. One mate of mine was bounced from pillar to post, and in the end he just got rid of his PC and went back to an Atari!

"I wanted something on which I could master and burn CDs, so Turnkey sold me a PC loaded with an Echo Gina 20‑bit soundcard. It has more outputs than I need, because I only ever record one item at a time. Since I bought the PC I haven't found the need to get any more gear." Pete agrees that there is little more to be desired. "We could record us sitting here now and then put us anywhere using this equipment — in space, on board a jet, in a huge storm — and it would really sound as if we were there. Another advantage is that you get so much done with this modern technology. On some of these Mac Rodgers episodes we do stuff in six hours that would have taken us six months on analogue. If it does crash and you lose a couple of hours it's nothing compared to months of hard work."

The Rodgers Method

Knowing that Bob and Pete have been mates for so many years, it comes as no surprise to learn that they have a highly refined approach to recording Mac Rodgers: their respective studio tasks are fixed and recording is tightly scheduled. Pete describes how it's done. "I write the story, then we meet and visualise the scenes. We laugh about it and discuss it until we end up with a list of sound effects. The list of sounds is like a recipe, and in this project we thought it was really important to have it very clearly envisaged in our heads before we even switched on the gear, because it was so complex. Fortunately, because we've been mates for years, when I say to Rob 'there's a bit here where Mac has to trip over a carpet slipper and fall out the window,' we both picture the same sequence and look for the same tripping and smashing sounds."

Once the pair have decided upon their sounds, they begin to seek out the samples they will need to do the job. "I got a Hollywood Edge sample CD free with my Akai S3000." explains Bob. "It's better than any of the BBC sound effects or anything like that. It has really good environmental sounds, and listening to them you really do feel like you're in the space. Some of them are more than 8Mb just for one sample, and some won't even fit in the Akai sampler.

"Most of the time I just record Pete's voice, because he can make so many funny noises. We've even sat here with our feet in buckets of paste with a mic, shouting instructions to each other. Once we needed a news report, and we wanted it to sound like it was outdoors, so we simply went out in the street and recorded our mate giving a news report, instead of trying to add some sort of ambience in here.

"For one episode we wanted the sound of a membrane stretching, and we tried everything. We had a sample of balloon‑stretching which we were layering up, but our recording still wasn't right. Then I accidentally nudged the keyboard across the work surface with my elbow, and that was it. Its rubber feet make a squeak and that was the best membrane yet. We didn't even have to switch the keyboard on. Thousands of pounds of equipment and we're doing that with it!"

All of the Mac Rodgers narration is recorded downstairs in Bob's daughter's bedroom using an Audio Technica AT4033 microphone fed into a dbx 286a mic preamp/processor. "The dbx has an exciter and a gate, so when someone decides to mow the lawn right in the middle I can gate it out," explains Bob. "Normally it's pretty good, but once we had to redo an episode because the vocal had an early reflection which was different to the other episodes. It might have been a variation in Pete's distance from the mic, so now we try to do all the mic stuff in the first take, so it has the same sound. We also hang up drapes and quilts to stop reflections, so Pete's enclosed in a cloth box. We do three or four takes, which always go straight onto DAT so that I'm not using up my hard drive space. I select the best and then put that into Sound Forge to chop and clean up."

Narrating Mac Rodgers is something Pete is very particular about, and his spoken parts form the framework for the samples and background music. Pete: "Just like music, it's got to swing, so I speak with the timing I want. If you're recording a song and you get to the chorus and feel it doesn't swing as much as the verse, you can put another note in or rewrite it, so we approach it like that. Then later, if we want to put a crack of thunder in that lasts 0.3 of a second but the gap between words is 0.2, we use Cool Edit to make the gap a bit bigger to fit the thunder."

Sorting The Samples

The studio where Mac Rodgers becomes a reality.

The studio where Mac Rodgers becomes a reality.

Aside from his PC, perhaps the most important item in Bob's studio is his Akai CD3000 sampler, which is used to audition sample CDs and to edit some of the samples transferred from the DAT recorder. "I tend to do all my editing on the Akai and then trigger the samples from Cubase, but if it's a big sample I'll put it on the PC's hard drive. I really like the Akai CD3000. I got the whole Akai library plus some sound effects. But creating drum loops in the Akai takes a lot of poncing about, so I do loops in the PC where it's a five‑minute job.

"I usually make a Sound Forge file for each episode, and everything I record for that episode goes into that file. Working from a script I can do that. I don't even try to pull the samples together until we have a mix or an editing day. Then I take the files into Cool Edit's multitracker, paste them together, mix them around and alter the volume so they become one track. After that we listen through and clean up a few things. Once you hear them in the mix, sometimes the samples have different qualities and need adjusting. I don't think of things in terms of kHz and EQ, I'm just listening for 'charisma'. Then I use Cool Edit's two‑track mixdown feature to burn the finished mix straight to CD."

At the time of writing, Bob was doing a lot of album‑mastering work for other people. Once again, Mac Rodgers had been put on the backburner, awaiting a possible BBC commission, but whether the project ever gets its full production or not, Bob and Pete remain happy that at last technology has enabled them to realise the vision and ideas which they first dreamt up over 20 years ago. Bob: "We're using the equipment in a more interesting way than we would by just doing music. It's the endless possibilities that excite me."

Main Equipment

The main rack, dominated by Bob's trusty Akai CD3000 sampler.

The main rack, dominated by Bob's trusty Akai CD3000 sampler.

- Pentium II PC (333MHz/64Mb)

- Event Gina Soundcard

- Tascam 38 multitrack recorder

- Akai CD3000 sampler

- Sonic Foundry Sound Forge 4.5 audio editor with plug‑ins

- Syntrillium Software Cool Edit audio editor

Gear List

A page from a real Mac Rodgers script, showing how much work goes into collecting and creating the necessary sound effects.

A page from a real Mac Rodgers script, showing how much work goes into collecting and creating the necessary sound effects.COMPUTERS/SOFTWARE

- Atari Mega2 ST

- Event Gina Soundcard

- Pentium II PC (333MHz/64Mb)

- Sonic Foundry Sound Forge 4.5 audio editor with plug‑ins

- Steinberg Cubase VST sequencer

- Syntrillium Software Cool Edit audio editor

RECORDING

- Akai CD3000 sampler

- Sony DTC 790 DAT player

- Sony K611s cassette deck

- Soundcraft 16:8:2 desk

- Studiomaster Stella amp

- Tannoy System 6 monitors

- Tascam 38 multitrack recorder

SOUND SOURCES & EFFECTS

- ART DXR delay unit

- Audio Technica AT4033 microphone

- Behringer Dualfex exciter

- Dbx 286a mic preamp

- Emu Proteus FX synth module

- Fender Jazz Bass

- Korg Wavestation synth

- Lexicon Alex effects processor

- Yamaha SPX90 multi‑effects

Inspiration

Bob explains where the inspiration for Mac Rodgers came from. "When we started there were albums coming out from Monty Python, The Bonzos, Vivian Stanshall, Derek and Clive, Spike Milligan, and they took people into a world of fantasy. We think that no‑one does that any more. When we're working we really do go into that world and before we know it it's four o'clock in the morning.

"We're big radio fans. The medium is superb and not used enough. If we ever lost the BBC in this country it would be a nightmare because they put so much great stuff on. They give people a platform and a chance, which you wouldn't get with a totally commercial radio station, where all you get is pap. We come from that generation where you turn your eyes off and take an audio journey."

Doing The Business

Bob has only ever sent two tapes to Sound On Sound, but he has managed to win Top Tape with both of them! The first was an ambient project called Luna Lazuli, which won in July 1997. Bob describes some of his most recent ventures. "For Luna Lazuli I recorded a band straight onto the Tascam and then I sat there chopping bits out. I used the lead vocal to make loads of loops. Before I knew it, it had started working, so I sent the demo to SOS and it won Top Tape. Then we did a whole album that way. I've just done a whole album with a friend just by cutting and pasting things from different sources. It's 40 minutes of music and we never played an instrument.

"At one stage I set up my own label and I was doing my own distribution, which was hard. I found myself ringing up shops in Wales and saying, 'I sent you 10 copies, did you receive them?' and it was like 'Yeah, I've sold five of them, do you want the money now or should I wait until I've sold all 10?' I couldn't do both that and make music, because it's a full‑time business‑management job. In fact, if anyone wants to go into music nowadays I'd recommend taking a course in business studies, not music. I would have loved someone to have taken it off my hands but it just fizzled out. I did enjoy doing it, though, and I learnt a lot from it all."