How can you ensure that your library music hits the spot? What better way to find out than to ask the people who buy it!

When clients use more library music, they spend less money on lawyers. Everyone wins, except the lawyers.In the first three parts of this series, we’ve looked at how to get started, met the library publishers who can give you work, and explained what it takes to be a good library music composer. This instalment is a chance to meet the clients: the people who can make or break your career, by deciding what music to use in their video productions.

When clients use more library music, they spend less money on lawyers. Everyone wins, except the lawyers.In the first three parts of this series, we’ve looked at how to get started, met the library publishers who can give you work, and explained what it takes to be a good library music composer. This instalment is a chance to meet the clients: the people who can make or break your career, by deciding what music to use in their video productions.

Even successful library music writers don’t usually know much about these people, and publishers don’t have much incentive to introduce writers to their clients. The net result is a strange separation, which can leave composers in the dark about what is good and bad in what they produce. So let’s lift the veil a little and see what goes on in darkened editing suites, where your worth is reduced to a waveform and track title in time-pressured music searches. Most of the interviewees we’ve talked to here are operating towards the high end of the market, representing the people who put the music into advertising, TV shows and movie trailers.

A Step Back

Who you gonna call? Library publisher, pop star (commercial music) or composer (commissioned music)?Before we meet these clients, a brief recap is in order. Library music, also known as ‘production music’, is a long-established business niche which involves creating finished albums of pre-cleared music. Today, these albums are distributed digitally through online music search engines to video professionals (‘clients’) around the world. Unlike ‘commercial music’ — conventional albums released by artists through record labels — library music has been designed with video use in mind, meaning that it’s usually instrumental, minimal enough to work under dialogue, organised into easy-to-understand genres, and supplied with different helpful variations and short edits. Because library music is ‘pre-cleared’, clients know in advance that they can use it, so don’t need to bring in lawyers to negotiate rights and prices.

Who you gonna call? Library publisher, pop star (commercial music) or composer (commissioned music)?Before we meet these clients, a brief recap is in order. Library music, also known as ‘production music’, is a long-established business niche which involves creating finished albums of pre-cleared music. Today, these albums are distributed digitally through online music search engines to video professionals (‘clients’) around the world. Unlike ‘commercial music’ — conventional albums released by artists through record labels — library music has been designed with video use in mind, meaning that it’s usually instrumental, minimal enough to work under dialogue, organised into easy-to-understand genres, and supplied with different helpful variations and short edits. Because library music is ‘pre-cleared’, clients know in advance that they can use it, so don’t need to bring in lawyers to negotiate rights and prices.

This system is great for the clients, as it’s cheaper and more tailored to their needs than commercial music. It’s also great for composers like you (who are usually referred to as ‘writers’ in the library industry) because the work can be creative and fun, and you can keep earning high royalties for decades as the music is reused around the world.

Who Are The Clients?

What happens in the edit suite, stays in the edit suite: video editors are usually operating under intense deadline pressure, and they need music that’s good, easily available and hassle-free.A variety of job titles are attached to video makers who choose music. At Hollywood trailer companies, the specialist ‘music supervisor’ plays a key role, alongside editors who are also given a lot of freedom as to what to use. TV shows have music supervisors, editors, producers and directors, who make the decisions within a chain of command, meaning that there are usually several people to please. Small indie producers, meanwhile, may be one-man operations directing, shooting the footage and choosing the music. Like you, they all spend sunny days in darkened rooms staring at software, but with perhaps more severe deadline pressures.

What happens in the edit suite, stays in the edit suite: video editors are usually operating under intense deadline pressure, and they need music that’s good, easily available and hassle-free.A variety of job titles are attached to video makers who choose music. At Hollywood trailer companies, the specialist ‘music supervisor’ plays a key role, alongside editors who are also given a lot of freedom as to what to use. TV shows have music supervisors, editors, producers and directors, who make the decisions within a chain of command, meaning that there are usually several people to please. Small indie producers, meanwhile, may be one-man operations directing, shooting the footage and choosing the music. Like you, they all spend sunny days in darkened rooms staring at software, but with perhaps more severe deadline pressures.

As you’ll see from the ‘Meet The Clients’ box, the interviewees I spoke to for this article come from a range of backgrounds: freelance producers and editors, a US TV editor, UK trailer editor, New Zealand promo editor, UK music licensing agent for advertisers, a Hollywood trailer music supervisor and a UK indie documentary producer. They were asked a range of questions about their use of music, and provided lots of fascinating insights to chew on.

The Importance Of Music

Nick Towle.It should be no surprise to find everyone agreeing that music is a fundamental part of a great trailer, advert, TV show or promo. For example, LA-based editor Nick Towle says “Someone once said that music is like salt: it makes everything taste better. Generally I’ll do my initial assembly without music, concentrating on story and performance, but then start adding music soon after. Music changes everything, from the pacing of scenes to the emotion you’re conveying. Sometimes it will even unlock the meaning of a scene for me, so it’s vital to get it right.”

Nick Towle.It should be no surprise to find everyone agreeing that music is a fundamental part of a great trailer, advert, TV show or promo. For example, LA-based editor Nick Towle says “Someone once said that music is like salt: it makes everything taste better. Generally I’ll do my initial assembly without music, concentrating on story and performance, but then start adding music soon after. Music changes everything, from the pacing of scenes to the emotion you’re conveying. Sometimes it will even unlock the meaning of a scene for me, so it’s vital to get it right.”

James Edgington from London’s The Editpool explains how music drives the impact of a trailer: “You could argue it is the most important and vital ingredient when creating a movie trailer or TV spot, as it creates the mood, style and tempo of the piece.”

TV music editor Guy Rowland agrees, saying “It’s vital. It can make or break a show. It can be the difference between something being funny or not, scary or not, boring or not.”

Advertising specialist Dominic Caisley of London’s Big Sync Music comments on music’s ability to reach out and affect the audience emotionally: “We believe that the right music can make an ad campaign truly memorable and engaging. We want the content to entertain, and music will do that, but we also want to connect with the audience. Music has the ability to not only entertain but also evoke an emotion, spark a memory, move us physically and emotionally, transport us to a time and place, as well as provide a narrative to the action on screen.”

UK producer Emma Smalley explains the key role that music choices play in planning. “The majority of creatives, directors and clients that we work with specify the importance of music in the production. More often we’re finding that it has been considered from the beginning of the script and brief and the conversations around music are always ongoing.”

The BBC’s Matt Tidmarsh starts with the music and lets it dictate the pacing: “Getting the right track at the right time or changing it to affect the mood makes the difference between a good and great sequence. I always build my edits around music, it makes everything flow.”

Composer takeaway: Remember how important you are as a composer in helping your clients achieve a deep emotional effect. Music is always high on their agenda, and if yours works well, they’ll use more — so make it expressive, with a strong visual end-use in mind.

Library Music Versus The Alternatives

“I know, isn’t it simply dreadful! He actually composes library music!”When clients need music, they have three sources to choose from: library music, where the tracks are pre-cleared and organised according to genres on online music search engines; commercial music, which is anything released by a record label for consumption by the general public; and commissioned music, also known as ‘custom music’ and ‘bespoke music’, where a composer is hired to create specific music to a brief.

“I know, isn’t it simply dreadful! He actually composes library music!”When clients need music, they have three sources to choose from: library music, where the tracks are pre-cleared and organised according to genres on online music search engines; commercial music, which is anything released by a record label for consumption by the general public; and commissioned music, also known as ‘custom music’ and ‘bespoke music’, where a composer is hired to create specific music to a brief.

Each option has its pros and cons, but library music has thrived in TV and advertising thanks to advantages in budget, speed and format. Which is to say, it’s cheaper, makes it quicker to find great finished tracks that work, is pre-cleared so needs no lengthy negotiations with artists, managers, publishers and record labels, and the music is formatted to work well with video, meaning that it’s offered in various versions, categorised according to the end use, designed to work under dialogue, with stems often supplied to give extra flexibility.

Guy Rowland says that although all the options have their advantages and disadvantages, library music is popular in TV for good reasons: “Library is an instant hit. It can set the right tone in a heartbeat, whereas commissioning can take a long time, and to get good commissioned music with live musicians can be expensive. Library can help you sell production value: the quality can be phenomenal, and it’s also quick and easy to be totally diverse. You can have opera followed by dubstep followed by Bulgarian folk, and you can have it all sourced, spotted and edited in about five minutes. What’s not to like?”

Michael Sherwood.Mike Sherwood appreciates the way that good library music can inspire editors. “Custom is great because you have so much control, but there is so much good music out there already that it can often be more advantageous to my editors to be inspired by music with true passion behind it and any unexpected elements within it.”

Michael Sherwood.Mike Sherwood appreciates the way that good library music can inspire editors. “Custom is great because you have so much control, but there is so much good music out there already that it can often be more advantageous to my editors to be inspired by music with true passion behind it and any unexpected elements within it.”

Dominic Caisley acknowledges that the lower price is an attraction, but won’t rule library music out even for high-end jobs. “Price is obviously a key driver for using library music, but in this day and age, we would consider library music for any brief, no matter what the budget.” He also appreciates the time saved by not having to clear the music: “Time is the other most important commodity, and so having a wide range of pre-cleared music at one’s fingertips definitely gives library an advantage over custom and commercial tracks.”

Matt Tidmarsh also notes that library has a speed advantage over commissioned music under deadline pressure. “If a track has been commissioned, it’s often requested to be written to pictures. This has huge benefits, as the track can really work with the pictures, but the nature of the majority of productions I work on is that you’re editing/re-editing to meet various demands right up to the point when you have to deliver, and it’s not really feasible to send tracks back and forth to the composer at this time.”

James Edgington.James Edgington appreciates the simplicity of clearing licences, and the way library music is written with his end use in mind. “Library music is much easier to clear, and is quite accessible. Sometimes, clearing commercial music can become slightly complicated, depending on who owns the publishing and masters of a track. The library music we usually use has been written and composed specifically for trailers, so cutting the visuals and the track can easily complement each other.”

James Edgington.James Edgington appreciates the simplicity of clearing licences, and the way library music is written with his end use in mind. “Library music is much easier to clear, and is quite accessible. Sometimes, clearing commercial music can become slightly complicated, depending on who owns the publishing and masters of a track. The library music we usually use has been written and composed specifically for trailers, so cutting the visuals and the track can easily complement each other.”

This is not to say that library music is the only game in town. Some advertisers might want nothing less than the Beatles, and be willing to pay for it, and excellent commissioned music can beat library music by being written perfectly for the job. Nick Towle notes: “There’s nothing better than working with a fantastic composer. For example, on Turn: Washington’s Spies we’ve been lucky to have Marco Beltrami and Brandon Roberts who have done us proud — but sometimes, you get a composer that isn’t quite as in tune with the show. In those cases it might have been better to work with a good library; you avoid that awful sensation of watching the finished show and thinking ‘I could have found something better than that!’”

Composer takeaway: If you invest your time in making high-quality library music, you can be confident that it has a prized role in the world of video professionals. Thanks to its unique advantages, including saving time and money, being pre-cleared, well-formatted, easy to find, inspiring and flexible, it is likely to remain the music of choice for many situations.

Snobbery & Prejudice

Having been in the library music industry since 2004, I’ve personally witnessed an era in which the high income-generating potential of library music has combined with an increase in production quality. Budgets have gone up to pay for more live instruments, and home recordists’ samples and plug-ins have become ever better. Meanwhile, there has been the sexy explosion of movie trailer music (a form of library music) with its oddball composers becoming the unlikely objects of worldwide fan adoration.

Nevertheless, it’s always been clear to me that there is a skeleton in the closet, a shady legacy that is revealed in subtle things that older veterans say. For example, some publishers who worked through the ’80s or ’90s will wince at the phrase ‘library music’ and insist on euphemistically calling it ‘production music’. For them, ‘library music’ carries connotations of cheesy ’70s synth-funk LPs and ’80s samplers that quickly dated. As Guy Rowland says, “Many years ago, lots of library music was just plain bad — cheap-sounding knock-offs. That’s far rarer now, standards have risen across the board.”

Meanwhile, at composer gatherings I’ve witnessed ‘media composers’ wrinkle their noses at library music, even though they earn less than library writers and their music is worse, suggesting that maybe they’ll “dash something off for library” or offer me some of their “rejected tracks”. Thanks, but no thanks. It goes without saying that those media composers are in turn being looked down on by film composers, and ‘art music’ composers look down on film composers, so blame the empty narcissism of humanity for this nonsense. Nevertheless, there is palpable anti-library snobbery lurking at the high end of the market, and it’s something to be wary of.

Dominic Caisley.Dominic Caisley works with big brands who harbour this legacy of suspicion and aims to make sure it doesn’t influence their decisions. “There can still be a stigma attached to library music, and it’s not unknown for us to take off any library reference when presenting to clients.”

Dominic Caisley.Dominic Caisley works with big brands who harbour this legacy of suspicion and aims to make sure it doesn’t influence their decisions. “There can still be a stigma attached to library music, and it’s not unknown for us to take off any library reference when presenting to clients.”

He also relates one cunning experiment that both revealed and overcame such prejudices: “Once we presented some library tracks to a creative team who dismissed them all. The next day we changed all the library tags to made-up band names, mixed up the order and presented the same 10 tracks to the creative team, telling them these were the latest, coolest emerging artists. They selected three to be presented to the brand.”

Composer takeaway: Library music has a better reputation than in days gone by, but you must be as good as or better than commercial producers and media composers to help disprove lingering doubts and keep raising standards for the industry.

Restrictions, Approved Lists & Budgets

In the UK, the Mechanical Copyright Protection Society offers ‘blanket licences’ that allow licence holders to use music from any member library.There are often restrictions on what library music TV producers can use, because the broadcasters and production companies for whom they work need to be sure that the music is pre-cleared and affordable in order to avoid legal trouble and unexpected infringement bills. This means that your library publisher needs to have a contract or arrangement with those broadcasters and production companies guaranteeing no nasty surprises. Such deals in the US are referred to as ‘approved vendor lists’ with pre-agreed rates, or ‘blanket deals’, where networks pay the publisher a yearly fee to use anything. In the UK, if the publisher is an MCPS member you know that a deal is in place, because it is a key MCPS role to negotiate blanket deals with broadcasters. If they are not MCPS members, your publisher will need to have a direct deal instead or their music won’t be used.

In the UK, the Mechanical Copyright Protection Society offers ‘blanket licences’ that allow licence holders to use music from any member library.There are often restrictions on what library music TV producers can use, because the broadcasters and production companies for whom they work need to be sure that the music is pre-cleared and affordable in order to avoid legal trouble and unexpected infringement bills. This means that your library publisher needs to have a contract or arrangement with those broadcasters and production companies guaranteeing no nasty surprises. Such deals in the US are referred to as ‘approved vendor lists’ with pre-agreed rates, or ‘blanket deals’, where networks pay the publisher a yearly fee to use anything. In the UK, if the publisher is an MCPS member you know that a deal is in place, because it is a key MCPS role to negotiate blanket deals with broadcasters. If they are not MCPS members, your publisher will need to have a direct deal instead or their music won’t be used.

Guy Rowland.As Guy Rowland says: “With the BBC, there’s something called the MCPS blanket licence agreement. Anything in the agreement is fair game to use at will, anything outside can be a nightmare.” On a personal note, though, I ought to add that I have met occasions where the opposite applies, and the use of non-MCPS libraries is encouraged because they have less onerous licensing restrictions.

Guy Rowland.As Guy Rowland says: “With the BBC, there’s something called the MCPS blanket licence agreement. Anything in the agreement is fair game to use at will, anything outside can be a nightmare.” On a personal note, though, I ought to add that I have met occasions where the opposite applies, and the use of non-MCPS libraries is encouraged because they have less onerous licensing restrictions.

In the US, Nick Towle has less freedom of choice. “As an editor, I don’t have much say as to which music library we use.” This is because US music libraries either have to have a blanket deal, where the network pays an annual fee to use anything they want, or be on the network’s ‘preferred vendors list’, where rates have been agreed in advance. These deals have to be negotiated individually between library and broadcaster.

However, like many editors, Nick has bitten back when the management try to control his options too much: “I worked on one show where the production company somehow got a cut of the royalties from one of the music libraries. So the powers that be were always trying to get us to use that library, and of course it was absolute garbage. Strangely, in the final mix 99 percent of the music ended up coming from the other libraries that the editors had access to. Can’t imagine how that happened!”

Outside of the TV world the choice of music is more flexible. Dominic Caisley, a UK music agent for major advertising brands, has “no restrictions other than budget and artist approval. The right song can come from any nation, any label or publisher, library or composer. We have great relationships with many music sources, but we take pride in our unbiased approach. It’s always about the music.”

Also usually working outside of TV restrictions is Emma Smalley, who tells us: “Creative, clients, context, pace, schedules, there’s a lot that affects the final choice of music. It always comes down to what works in the edit, and what makes everyone finally agree!”

Composer takeaway: When considering what libraries to write for, if their main market is TV you need to check that they have deals in place with broadcasters and production companies. If their main market is advertising (and movie trailers are a form of advertising) there are fewer restrictions.

Helping Clients

Not all music supervisors at library publishers display as much helpful enthusiasm as their clients would like.Rather than being passive, a library music publisher should be a helpful partner to the end user. Publishers should offer a contact for quick help finding tracks — a service known as ‘music supervision’.

Not all music supervisors at library publishers display as much helpful enthusiasm as their clients would like.Rather than being passive, a library music publisher should be a helpful partner to the end user. Publishers should offer a contact for quick help finding tracks — a service known as ‘music supervision’.

All publishers should fall over themselves to help clients find music, but Extreme Music (a Sony label) in particular have made a great impression on Nick Towle. “Extreme has worked really well for a number of shows I’ve edited. The ability to chat online with their music supervisors really helps you find tracks quickly, especially when you’re new to the library — as an editor you always have a deadline bearing down on you, so that is a Godsend.”

Dominic Caisley emphasises the importance of good human help: “I would say to music supervisors: make sure you connect personally and maintain that relationship. Make yourself indispensable, the reliable ‘go to’ person in times of crisis. Web sites are getting better and smarter, but you can’t beat a good supervisor who knows their catalogue. If a supervisor at a library presents tracks that are not on brief or don’t match the reference track, the chances are I won’t go back to them.”

Emma Smalley.Emma Smalley has the problem of receiving too many tracks that don’t fit the brief, which takes up precious time. “Although we have fantastic contacts from several catalogues who turn out great searches for us, there’s still the long process of listening through a lot of tracks that aren’t right, to find the few that may work.”

Emma Smalley.Emma Smalley has the problem of receiving too many tracks that don’t fit the brief, which takes up precious time. “Although we have fantastic contacts from several catalogues who turn out great searches for us, there’s still the long process of listening through a lot of tracks that aren’t right, to find the few that may work.”

Composer takeaway: It’s not easy information for you to extract from them, but try to figure out if your publishers are making themselves popular with clients by giving them fast, high-quality music search playlists, or making themselves unpopular by responding slowly with tracks that don’t fit the brief. Time-pressured clients go first to the most helpful publisher they know, because it will save them time and make their jobs easier.

Variety & Quality

It reduces stress for clients when they develop trust in a small number of libraries that they keep returning to. To get to that point the client needs to know that there’s plenty of variety on offer and that the quality will be consistently high.

Richard Alexander.Richard Alexander emphasises the importance of musical diversity: “Quality of music is important for sure, but variety is key for someone like me as I move up and down through those gears and change the pace.”

Richard Alexander.Richard Alexander emphasises the importance of musical diversity: “Quality of music is important for sure, but variety is key for someone like me as I move up and down through those gears and change the pace.”

The huge range offered by KPM explains why Guy Rowland keeps going back to them: “Their quality threshold is very high across a huge variety of music. They have an archive going back many decades — I often search for authentic archive music.”

Tim Hansen explains why a need for speed requires trust, and why trust requires quality: “When I’m in a hurry, I go to what I know and who I can count on, so consistency of quality is a biggy. There are a lot of fantastic libraries out there: Audiomachine, Gothic Storm, Really SlowMotion, Posthaste, Ninja, Sonoton, Two Steps, Bam, Velvet Ears, Xseries, Directors Cuts, Volta, InTheGroove to name a few. Their production values are up there with the best.“

Tim Hansen.Composer takeaway: Make sure you personally maintain the highest possible quality standards to help build and maintain your publisher’s reputation. Also check that your publisher covers a good musical range and maintains permanently high standards. If they’re a trusted brand, your music is more likely to be discovered in their catalogue and used.

Tim Hansen.Composer takeaway: Make sure you personally maintain the highest possible quality standards to help build and maintain your publisher’s reputation. Also check that your publisher covers a good musical range and maintains permanently high standards. If they’re a trusted brand, your music is more likely to be discovered in their catalogue and used.

Authenticity, Variety & Finality

My interviews with end users generated some important advice for writers, which can help you to make your music more successful. In particular, your music needs to sound authentic, with plenty of development and variation, and strong endings.

Using real musicians is often the key to creating authentic music.Authenticity might be defined as sounding genuine and real, not fake, and could mean using live instruments (or at least exceptionally realistic and expressive samples), knowing your genre deeply and being emotionally involved in your music. Making authentic music is a matter of caring about and enjoying what you’re doing and expressing real emotions. Michael Sherwood: “Make what you’re good at and enjoy making. Nothing sours me on a track like inauthenticity.”

Using real musicians is often the key to creating authentic music.Authenticity might be defined as sounding genuine and real, not fake, and could mean using live instruments (or at least exceptionally realistic and expressive samples), knowing your genre deeply and being emotionally involved in your music. Making authentic music is a matter of caring about and enjoying what you’re doing and expressing real emotions. Michael Sherwood: “Make what you’re good at and enjoy making. Nothing sours me on a track like inauthenticity.”

Matt Tidmarsh.Universal is Matt Tidmarsh’s go-to library precisely because of its authenticity. “I like to use Universal Production Music. I think their tracks generally sound more rich and authentic.”

Matt Tidmarsh.Universal is Matt Tidmarsh’s go-to library precisely because of its authenticity. “I like to use Universal Production Music. I think their tracks generally sound more rich and authentic.”

Many clients identified monotony — sticking to one vibe and staying there — as a pet hate. They need development and variation to help guide and follow the changes and dynamics of their video. As James Edgington says: “A good piece of library music for a trailer is one that can take the viewer on a journey. When a track will just repeat the same beats, bars and rhythm, it can become quite boring and restrict the trailer from moving in the direction you may want to take it.”

Nick Towle agrees. “We need different sections of a piece to help us score the ebbs and flows of a scene. One of the most common notes we’ll get from producers is ‘This music doesn’t go anywhere.’”

Emma Smalley echoes the need for changes in the music. “The ones that stand out and make it to the final edit have variation in them. A drop, or build: moments that you can edit into the final film that help the energy, story and pace, and give the editor more to play with.”

Video editors are permanently faced with the problem of the music needing to end well. This means avoiding fade-outs, which can’t be sync’ed to an edit, or sloppy stops that happen right at a key moment in the video as a scene ends and the mood shifts.

As Guy Rowland puts it: “Endings can be a nightmare. If I like the sound of a track, often the first thing I check is if it has an ending I can use.”

Endings are an issue for Nick Towle too. “For me the worst offence is not having a proper ending to the track, just a fade. Editing software is quite capable of fading out a cue, so don’t be lazy: give us an actual ending, ideally with a sting!”

Composer takeaway: Keep it real; make sure your music changes and develops to help film makers tell a story; end well!

Final Thoughts

In this journey into the video maker’s world we’ve picked up many specific requests. If a publisher is to be trusted enough to become someone’s go-to library, they need to supply good metadata, good endings, stems, music that develops and changes rather than being monotonous, consistently high quality, authenticity and a varied range in their catalogue. They also need to offer helpful music supervision, suggesting only what film-makers need and delivering it quickly. Video makers desperately need these go-to libraries, because that trust will save them time that they can’t afford to spend auditioning hundreds of tracks from far and wide.

We’ve also learned that music plays a central role in achieving the clients’ aim of making great videos, and that although library music is often their best option, they sometimes have restrictions on what they can use. So, keep making great music with confidence that it has a receptive end user, but make sure your publishers are on those important pre-cleared ‘blanket deal’ or ‘preferred vendor’ lists. We’ve also heard that the clients are all under terrible deadline pressures, but still want to make great videos that have a big emotional impact on the viewer. Ultimately, then, just two major factors are driving all of their music decisions: a lack of time and a desire for powerful results.

Whatever you do, therefore, help video-makers to be amazing, and quickly!

All About Library Music: Part 1 Getting Started

All About Library Music: Part 2 The Business

All About Library Music: Part 3 The Composer

All About Library Music: Part 4 The Client

All About Library Music: Part 5 Networking

Meet The Clients

- Emma Smalley is a producer at London’s The Virtual TV Department, which partners with ad agencies, TV shows and films.

- Matt Tidmarsh is a freelance editor working mainly for the BBC.

- Guy Rowland is a freelance music editor who works for the BBC.

- Los Angeles-based Nick Towle has edited Emmy-winning reality TV shows and currently works on Turn: Washington’s Spies for AMC.

- James Edgington is a trailer and promo editor at London’s The Editpool.

- Dominic Caisley is the CEO and founder of Big Sync Music, which helps major global brands find and license music for their campaigns.

- Tim Hansen is a New Zealand-based promo and ad producer for clients including Sky Movies.

- Michael Sherwood is the music supervisor at Hollywood-based Big Picture Entertainment. Recent major movie trailer credits include Ghost In The Shell, Baywatch and Allied.

- Richard Alexander is an independent UK TV documentary maker focusing on real unfolding stories that take years to film.

Providing Stems

Most DAWs make it relatively easy to create stem tracks from your mixes, and these can be very useful to video editors.Increasingly, video editors like to have access to stems: a small set of multitracks that can be combined and adjusted to make up a final mix. Nick Towle is not unusual in wanting to add a personal touch by rebalancing the mix using stems. “It’s very useful to have the individual stems available — bass and drums, keyboards and so on — as well as the final mix. It makes the cues a lot more flexible and really allows us to get more creative in the edit.”

Most DAWs make it relatively easy to create stem tracks from your mixes, and these can be very useful to video editors.Increasingly, video editors like to have access to stems: a small set of multitracks that can be combined and adjusted to make up a final mix. Nick Towle is not unusual in wanting to add a personal touch by rebalancing the mix using stems. “It’s very useful to have the individual stems available — bass and drums, keyboards and so on — as well as the final mix. It makes the cues a lot more flexible and really allows us to get more creative in the edit.”

Promo and ad producer Tim Hansen agrees: “We kind of expect stems these days. We don’t always use them, but it is great to have them.”

Now more than ever, therefore, your publisher should be asking you for stems and you should be supplying them. They can take time to export, but with a bit of smart grouping and bouncing, it can be done pretty quickly in most DAW programs. Just ask around for tips how to speed up this process.

Better Metadata

Library music publishers do many essential things to help you earn money, including giving you feedback to improve your mixes; marketing your music through promo videos, good sleeve design and catchy album concepts; hiring sales teams; managing international agent networks; registering your music on search sites with track descriptions and key words (metadata); registering them with royalty collection agencies, and other mountains of admin. But some get more things right than others. Our client interviewees generally agree on what they love and loathe from library publishers, so take note and try to check that your publisher is doing their best on your behalf!

Library music publishers do many essential things to help you earn money, including giving you feedback to improve your mixes; marketing your music through promo videos, good sleeve design and catchy album concepts; hiring sales teams; managing international agent networks; registering your music on search sites with track descriptions and key words (metadata); registering them with royalty collection agencies, and other mountains of admin. But some get more things right than others. Our client interviewees generally agree on what they love and loathe from library publishers, so take note and try to check that your publisher is doing their best on your behalf!

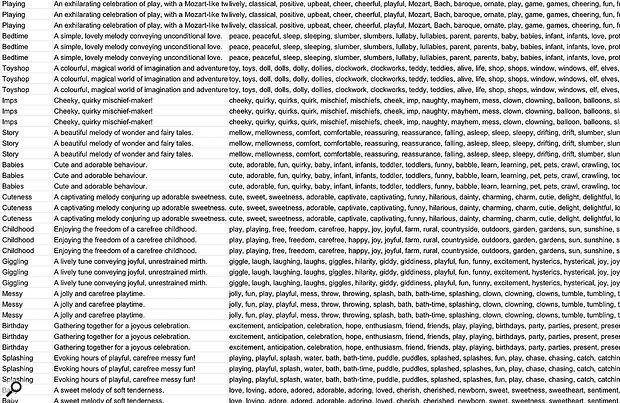

Metadata can make or break library music.

Metadata can make or break library music.

Metadata, also known as ‘tags’, is a whole bunch of information embedded in every audio file. It includes key words (to help search engines), track descriptions, details of the composer’s name and performing rights society, details of the publisher and more. Creating this information is heavy work for the publisher, because there’s no easy way to beautifully describe thousands of tracks without listening carefully to each one and writing tailored descriptions that will help the end user. Clients on deadlines quickly scan through track descriptions for clues and throw words like “fast skipping dogs puppies sunshine happy” into the search engine, hoping something great turns up quickly and saves their lives.

Matt Tidmarsh wants more detail from the descriptions. “The more detail in descriptions of tracks the better, including at what time sections change in the tracks.”

Guy Rowland is put off by the practice of ‘spam-tagging’ that some publishers indulge in, where they will fill in as many key words as possible even if they aren’t relevant, just to get search engine hits. “You’re usually up against deadlines, so you don’t want half an hour of fruitless searches with a mediocre library that spam-tags everything. There are libraries I avoid because they do precisely this.”

Amusingly, he also notes one company who have the opposite problem: good metadata but bad music. “There’s one particular company who clearly employ one person to do the track descriptions. He or she is in the wrong job — they are genuinely hilarious, ultra-cynical, acerbic descriptions that sometimes read more like novellas than track descriptions. Trouble is, the music never lives up to it. It’s nearly always just a bit crap.”

Michael Sherwood doesn’t want his time being wasted by badly organised metadata. “I hate bad, incomplete, or inconsistent metadata. I still have to always check and almost always edit the metadata on every file I bring in to my collection, and it’s a huge time-suck.”

As a composer, therefore, you need to ask to look at the metadata for your tracks. Does your publisher write helpful descriptions or cut-and-paste garbage? Are their key words relevant, or do they have tons of generic words that could apply to anything? Worse still, are the descriptions poorly written, or is some information incomplete or incorrect?