Like any way to make a living, library music has its pitfalls. We help you look out for some of the biggest!

This series of articles about library music has, on the whole, been optimistic and encouraging for composers. And so it should be: many seasoned library writers are making five-figure royalty incomes after years of composing, and they are generally enjoying the creativity, freedom and flexibility of their careers. That said, a lot can go wrong along the way, and this month, we present a compendium of sorry tales of liars, cheats, idiots and AI overlords who will try to undermine your daily attempts to eke a gentle living making library music. This isn’t about fear-mongering, though: it’s a map of traps, to help you avoid them.

If you’re particularly careless or unlucky, a copyright dispute could leave you penniless and homeless.A famous life-coach — well, Jez from the TV series Peep Show — once advised: ‘Just sign and recline.’ Signing contracts without reading them might seem like the path to an easy life, and many library writers do just that, but as we’ll see, this attitude could leave you bankrupt or in jail. Perhaps, therefore, Jez-sympathisers ought to peek at some horrors, so they can be just scared enough to avoid the worst of them. Let’s get off to a spicy start with cheats, liars and scams. (Or, for ongoing court cases, alleged cheats, liars and scams.)

If you’re particularly careless or unlucky, a copyright dispute could leave you penniless and homeless.A famous life-coach — well, Jez from the TV series Peep Show — once advised: ‘Just sign and recline.’ Signing contracts without reading them might seem like the path to an easy life, and many library writers do just that, but as we’ll see, this attitude could leave you bankrupt or in jail. Perhaps, therefore, Jez-sympathisers ought to peek at some horrors, so they can be just scared enough to avoid the worst of them. Let’s get off to a spicy start with cheats, liars and scams. (Or, for ongoing court cases, alleged cheats, liars and scams.)

Chinese ‘Collection’ Societies

In most countries, when music is broadcast on TV or the radio, the broadcaster has to pay performance royalties to the collection society. Also known as the PRO or Performing Rights Organisation, this society then pays the writers. The main collection society in the UK is the Performing Right Society (PRS), and there are similar groups around the world.

According to a source who wishes to remain anonymous, the history of royalty collection in China has been quite colourful. “A few years ago the PRO had trouble collecting broadcast income from broadcasters who had never been educated about the concept of performance royalties, so it employed local gangs of criminal thugs to go out and collect the money by force. This proved lucrative initially — so much so that multiple new gangster-PROs sprang up to get in on the action, sometimes registering the same music under different writer names and then disappearing without trace, with the writers never being paid. A recent government crackdown brought some of this to an end by banning the creation of new PROs, but there remains a tangled situation of broadcasters having to pay multiple PROs for the same piece of music because of the historic mess.

Composer takeaway: In some parts of the world they don’t have the centuries of copyright laws that we’ve had in the West, and it will take time for the culture to change.

The Spanish ‘Wheel’

Not that the West is necessarily a beacon of integrity and transparency. In 2017, 18 people were arrested in Spain as part of a police investigation into an alleged scam known as ‘the wheel’ (la rueda). Employees of Spain’s SGAE Performing Rights Society were accused of creating low-quality musical arrangements of public-domain works, while TV stations were listed as publishers; the stations then repeatedly broadcast this music late at night, clocking up millions of Euros in broadcast royalties. The police also accused TV company employees of taking “financial rewards” for helping to favour this music for airtime.

This follows years of notoriety, including one former SGAE executive Pedro Farré being jailed after being arrested with eight others for misappropriation of funds in 2011. On his release he published a colourful book about splurging his SGAE expense account on prostitutes and drugs, while complaining about being the only one to be found guilty.

Composer takeaway: There’s not much you can do about alleged foreign royalty collection scams, but it can’t hurt to keep an extra eye on your friendly local society — who are, after all, exposed to huge flows of cash, close relationships with broadcasters and potential temptation. Beware of getting roped in to anything dodgy: someone may well convince you and themselves that their bribe is a ‘sales commission’, and their royalty scam is a ‘business model’.

Composer Infringers

As a publisher, I’ve heard of new and inexperienced composers going directly to clients and undercutting high-quality publishers with low prices and bad music. To offset complaints about poor quality, some writers blatantly steal other, better writers’ work, combining loops from different tracks to cover their mischief. They sometimes get away with it, but as the power of tune-recognition software grows, they are starting to get their clients into trouble for copyright infringement.

I’ve also heard of composers writing the same music for two different publishers with whom they have supposedly exclusive agreements, just changing the main melody and calling it a new work. Perhaps it’s the naivèté of new writers, but it can cause problems for everyone: remember that the recording copyright exists in all of the recorded music, including the background layers.

A similar story I heard involved a composer reusing the same melody for two different major publishers, a dodge which remained undetected until one of the tracks was used as the backing on a hit single! The composer then ended up caught between warring publishers, who both blamed him. Luckily they agreed a royalty split, but the writer’s reputation was damaged.

Sometimes theft and misrepresentation is more blatant, as composer Deryn Cullen found out. “My husband and I have been composing and recording music in partnership since 2006. Most of our material is destined for libraries, and some we have released, both on our own and through a record label. Until recently we never dreamed that anyone would have the audacity to appropriate, retitle and release our music as their own but we discovered an act of theft, fraud and misrepresentation when we were adding some of our earliest cues to a non-exclusive library, and a couple of them were flagged by their content ID [tune-recognition software] system. After sending sufficient proof of ownership, the library released the information they had against the tracks and we were horrified to discover that someone in North America had released an entire 16-track album consisting entirely of music we had written and recorded between 2006 and 2013. Further investigation revealed that we were not the only artists whose music he had claimed as his own. We are still in the process of disputing and having the release removed.”

Elsewhere, an odd story circulated a few years ago of a young ‘epic music composer’ showing off his music alongside photos of his incredible film score awards. Except none of the awards were his, and none of the music was his. He didn’t try to profit from this deception, so who knows if he was a fantasist, hoaxer or troll, but he recently resurfaced doing exactly the same thing under a new name and was quickly exposed by vigilant composers.

Composer takeaway: You can’t stop someone claiming your work as theirs, but tune-recognition software can catch claim clashes, and if you are the original writer you are likely to have convincing proof of ownership such as old emails, project files, PRO registrations and style similarities to your other music. A few emails to the companies that host the music should therefore get it removed, even if you don’t have the means to chase the thief into court. As for intentionally infringing copyrights yourself, by reusing material or stealing someone else’s: just don’t do it. You’ll get caught and will never build a good reputation. To protect yourself against genuine slips where you infringe copyrights unintentionally, you can avoid the worst possible outcome (bankruptcy!) by getting professional indemnity insurance, also known as Errors and Omissions Insurance in the USA.

You Want Paying?

Composer Marie-Anne Fischer.Writer Marie-Anne Fischer relates one odd tale of a client who wasn’t so much a cheapskate as a freeskate. “A Canadian client asked me if I could add an ending to somebody else’s library track, which he had licensed and needed a big epic ending. After asking permission from the composer and the library, I worked on an ending for him which was to be used on some footage of a marathon. He wanted it quickly so I dropped everything else and created it for him.

Composer Marie-Anne Fischer.Writer Marie-Anne Fischer relates one odd tale of a client who wasn’t so much a cheapskate as a freeskate. “A Canadian client asked me if I could add an ending to somebody else’s library track, which he had licensed and needed a big epic ending. After asking permission from the composer and the library, I worked on an ending for him which was to be used on some footage of a marathon. He wanted it quickly so I dropped everything else and created it for him.

When I wrote to ask whether the track was suitable he said ‘Yes, perfect thanks.’. When I replied that we hadn’t discussed a fee yet he became terribly aggressive, thinking that I was in the wrong wanting him to pay for the ending, so I just left it.”

When the eagle meets the dragon... it’s hard to get paid for the trailer music.On an altogether larger scale, in 2014, my Gothic Storm trailer music company was happy to hear our music used in the main worldwide trailer for a new Jackie Chan film called Dragon Blade. The only snag was that we had never granted them a licence to use our music. Investigations revealed that the film had been made by a state-owned Chinese film company. Next we found the small Chinese production company who made the trailer, and asked them to pay for a standard licence. They replied offering us $50, explaining that this was what they pay local composers.

When the eagle meets the dragon... it’s hard to get paid for the trailer music.On an altogether larger scale, in 2014, my Gothic Storm trailer music company was happy to hear our music used in the main worldwide trailer for a new Jackie Chan film called Dragon Blade. The only snag was that we had never granted them a licence to use our music. Investigations revealed that the film had been made by a state-owned Chinese film company. Next we found the small Chinese production company who made the trailer, and asked them to pay for a standard licence. They replied offering us $50, explaining that this was what they pay local composers.

Fifty bucks for something this big was an insult to us and the composer, who gets 50 percent of the fees. A decision was therefore made to fight back, with lawyers chasing production and distribution companies in multiple countries. We also got YouTube and Facebook to take down the video from Jackie Chan’s pages and ran a spirited social media campaign, all the time reaching out to offer them a licence agreement at a reasonable rate, but to no avail. A few library industry insiders told us that no Western company has ever won a copyright case in China, and we were wasting our time — but out of the blue we got a $25,000 payment and a long and bizarrely worded letter of apology from someone, although we didn’t actually know who he was. He assured us that he would use our music as a first choice in future trailers, although we’re still waiting for those!

Composer takeaway: You can’t prevent people trying to rip you off, but if it’s a big-budget film with famous actors and international partners, it seems that you can embarrass someone into coughing up the dough with enough effort. For smaller productions it’s a mixed picture in China and many other countries. We know lots of good Chinese companies and there is progress, but there isn’t currently a strong legal pressure on less reputable companies to bother paying foreign music companies for using their music.

On The Receiving End

Robin Thicke: not smiling quite so much after the ‘Blurred Lines’ court case?The more music you write, the greater your chances of becoming a target of copyright infringement claims. Famous legal cases crop up regularly in the press and highlight the vagueness of what constitutes a musical copyright infringement. Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams famously had to pay the estate of Marvin Gaye $7.3m in 2015 over supposed similarities between ‘Blurred Lines’ and Gaye’s ‘Got To Give It Up’, which were by no means universally acknowledged. It’s a reminder that legal outcomes are decided by juries and judges who have no expert knowledge, and can be swayed by unfortunate quotes from writers about what inspired them and the testimony of expert witnesses.

Robin Thicke: not smiling quite so much after the ‘Blurred Lines’ court case?The more music you write, the greater your chances of becoming a target of copyright infringement claims. Famous legal cases crop up regularly in the press and highlight the vagueness of what constitutes a musical copyright infringement. Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams famously had to pay the estate of Marvin Gaye $7.3m in 2015 over supposed similarities between ‘Blurred Lines’ and Gaye’s ‘Got To Give It Up’, which were by no means universally acknowledged. It’s a reminder that legal outcomes are decided by juries and judges who have no expert knowledge, and can be swayed by unfortunate quotes from writers about what inspired them and the testimony of expert witnesses.

Back in the library music world, a current legal case has seen the small family-run Australian company who represent our music being dragged to court by Eminem. This is over a track called ‘Eminem-esque’, which was written in the US, published by a US library, and only represented in Australia and New Zealand by these sub-publishers. The infringement allegations arose after it was used on a TV campaign by a New Zealand political party. The press had a field day laughing at the idea of New Zealand politicians taking on Eminem in court, but the upsetting reality is that a small company unwittingly stumbled into liability threats through something they had very little control over.

The case isn’t settled at the time of writing, but it’s a sobering reminder that you never can predict when you might end up in court. As the writer, you have the ultimate liability in cases of copyright infringement, because you sign a publishing agreement guaranteeing that you own the copyright and accept all of the penalties if you don’t.

Composer takeaway: The more music you write, the greater the chance you’ll be the target of an accusation, fair or unfair. As before, your best chance of avoiding financial ruin is to take out professional indemnity insurance cover (Errors and Omissions Insurance in the USA).

YouTube Infringers: Your Best Mates?

As a side note, the bane of composer’s lives a few years ago was their music being used on amateur YouTube videos without permission. Now that YouTube is a big seller of advertising, however, good money can be earned for unapproved uses via advertising revenue. Companies like AdRev in the USA help publishers and composers to recover income that can sometimes be significant; for example, our company earns $1000 per month and rising from unlicensed uses of our music on YouTube.

Composer takeaway: Once a threat to contain, YouTube infringement has become a gravy train to milk.

Rip-off Publishers

Vincent Varco, library music composer.A whole nest of vipers is the world of low-rent publishers who will take your music and give you little in return. Much of this ground has been covered in Part 2 of this series, where we talked about the different types of library companies, but, to repeat some of that advice, ask other composers for recommendations, and don’t dismiss what sounds like a bad deal if you know that a company are making good money for their writers.

Vincent Varco, library music composer.A whole nest of vipers is the world of low-rent publishers who will take your music and give you little in return. Much of this ground has been covered in Part 2 of this series, where we talked about the different types of library companies, but, to repeat some of that advice, ask other composers for recommendations, and don’t dismiss what sounds like a bad deal if you know that a company are making good money for their writers.

US composer Vincent Varco gives an example of one publisher who offered a buy-out figure (with no future royalties) of $2000 for 300 cues. Imagine the rate you’d have to write to make that worth your while! He also tells us of publishers who have deals with TV production companies where the publisher gives the TV company all of their future royalties and makes up the loss by taking half of the writer’s share. Arguably the real problem here is the TV company forcing publishers to give up their income, but unless the library-music world has slumped and this is the best deal you can get, I’d avoid this if you can help it.

Library music composer Paul Biondi.Another US composer, Paul Biondi, tells us of a similar experience, perhaps with the same company: “They said that they found themselves having to give away half or all of their publishing to the networks, so taking 50 percent of composing assured them that they would be making at least 25 percent. More disappointing to me, the library owner — a known composer — said he would be using his composing skills and knowledge in making cut-downs, which warrants half of the writer’s share.”

Library music composer Paul Biondi.Another US composer, Paul Biondi, tells us of a similar experience, perhaps with the same company: “They said that they found themselves having to give away half or all of their publishing to the networks, so taking 50 percent of composing assured them that they would be making at least 25 percent. More disappointing to me, the library owner — a known composer — said he would be using his composing skills and knowledge in making cut-downs, which warrants half of the writer’s share.”

Composer takeaway: Unless you have very strong evidence that it could earn you great money, only give away your writer share to co-writers or other people you’d like to reward (like performers or producers), not publishers or TV networks.

Incompetence

It’s not only swindling rogues who stand in your way. Another huge enemy is incompetence: publishers, collection societies and clients wasting your time and leaving you out of pocket by doing their jobs badly. For example, publishers who give incomprehensible, contradictory briefs and change requests to their writers are massive time-wasters. As one writer tells us: “Despite rarely having tracks rejected, the publisher’s new project manager rejected track after track, constantly asking for rewrites with incomprehensible and contradictory instructions. Halfway through I wondered if she was an idiot and started resubmitting old versions that she’d already rejected. Every single time it was ‘Wow, this is much better, thanks!’, and things ran much more smoothly after that.”

Another writer, Jamie Salisbury, relates the time his track was rejected over and over, with the mix being blamed. So, he asked a friend to do a new mix. The publisher initially approved it but then left it off the album, this time blaming the arrangement. Jamie had the last laugh, however: “A couple of months later it became the lead track on a KPM trailers album, and has become my second biggest-earning track, including extensive uses during the Cricket World Cup.”

Guy Rowland.Writer Guy Rowland has a story involving a famous singer he’s calling ‘Troy Illinois’. Guy was asked to write music exactly in ‘Troy’s’ style — for Troy’s own TV show! Bizarrely, Troy’s own music couldn’t be cleared for this use, but Guy’s every attempt to imitate his style was rejected. “Each time I got the same disappointing feedback from one of the 90 producers working on the thing: ‘It’s just not Troy Illinois enough.’ Finally, out of sheer unprofessional exasperation, I did something you should never, ever do. As a test, I actually submitted an edit of an actual 100-percent-genuine Troy Illinois song itself. No doubt you’re ahead of me, and already guessed the feedback I got. ‘It’s just not Troy Illinois enough.’ That, ladies and gentlemen, is the time to bail.”

Guy Rowland.Writer Guy Rowland has a story involving a famous singer he’s calling ‘Troy Illinois’. Guy was asked to write music exactly in ‘Troy’s’ style — for Troy’s own TV show! Bizarrely, Troy’s own music couldn’t be cleared for this use, but Guy’s every attempt to imitate his style was rejected. “Each time I got the same disappointing feedback from one of the 90 producers working on the thing: ‘It’s just not Troy Illinois enough.’ Finally, out of sheer unprofessional exasperation, I did something you should never, ever do. As a test, I actually submitted an edit of an actual 100-percent-genuine Troy Illinois song itself. No doubt you’re ahead of me, and already guessed the feedback I got. ‘It’s just not Troy Illinois enough.’ That, ladies and gentlemen, is the time to bail.”

Composer takeaway: Try to avoid working for publishers who give incompetent writer feedback. A politically perilous alternative is to complain to the boss about your bad experience. That approach might work if they trust you and have doubts about their staff, but it could easily backfire if they think you’re being difficult.

Errors & Oversights

Human beings are a mess: sloppy, slapdash, too busy to do things properly, forgetful, sleep-deprived, unmotivated, lazy, ill, hungover and working for companies who think they are fantastic because their old back catalogue is making millions, while actually no-one knows what they are doing. And they create computer systems with bugs that lose data.

That goes for publishers, clients and collection societies. Publishers forget to register tracks with rights societies, or fill in the wrong data so that your money goes to someone else, or no-one, or all to them. Most of my agents (international library sub-publishers), are great but I am constantly having to beg and browbeat one of them into releasing albums that they’ve been sitting on for up to a year — that’s a year of lost earnings for the writers. We once discovered that a foreign sub-publisher had overlooked some albums and never released them. We found that another was a year behind registering the music with their collection society. All of these delays lose money for our writers.

Meanwhile, TV producers will often forget to fill in the manual ‘cue sheets’ (forms that tell your collection society who wrote the music), partly because they are busy and partly because the TV networks have no great incentive to enforce it. Collection societies vary around the world in how organised they are and how successfully they enforce accurate royalty reporting from TV networks.

It’s hard to guess at the size of these problems, but since huge parts of the international music royalty system require the manual inputting and copying of data and these problems are familiar to anyone who looks closely into it, we can only assume it is rife and all writers are earning significantly less than they are owed. The US company Tunesat are helping to bring this to an end with their tune-recognition software, which monitors broadcasts around the world and gives you reports of music matches, and you can get started with a popular free version monitoring a small number of tracks. AdRev are also helping writers and publishers to catch infringements using YouTube’s similar ContentID software and then raise advertising revenue.

Composer takeaway: Check the accuracy of your writer and song information on your country’s performing rights organisation’s music search engine and whether your music is available as it should be on your publisher’s web site and those of their sub-publishers (agents) around the world. Get a free account with Tunesat and never assume that everyone knows what they’re doing. They really don’t.

Bad Luck

Sometimes things just don’t work out. For example, as a writer, my main library publisher had a change of personnel. My enthusiastic and inspiring mentor was replaced by someone who seemed to hate me, and the jobs soon dried up. Another misfortune saw my albums delayed for over a year when the company found themselves with too much music and decided to pause releases until they’d cleared their giant backlog.

And then, publishers have their misfortunes. They could get sued or make mistakes and go bust, putting your income in jeopardy. Or they could be bought out by a company that fails to promote your music, or have a few months of low sales, causing them to cut costs and leave your album on the shelf for a few months.

Composer takeaway: Some bad luck is inevitable, but you can avoid the worst of it by working for more than one publisher.

Outside Your Control

At the higher levels of the library industry, various battles rumble on, all of which could affect your income. That includes battles between performing rights societies (PROs) and streaming services like YouTube to secure higher royalties; between one country’s PRO and others (such as disputes over who should pay certain taxes); and between PROs and broadcasters, trying to secure better royalty rates or prevent them dropping. Then there are governments taking PROs to court for acting like price-fixing cartels, PRO board meetings that decide to award library music lower rates without asking anyone, and PROs lobbying governments to crackdown on piracy. All of this wrangling and more can cause short-term hiccups or long-term changes in your income levels.

More globally still, there are other common fears. One is that rising competition from new composers and budget publishers is creating a ‘race to the bottom’, where fees are being driven down to the point that no-one will be able to make a living any more. I’ve been hearing this for 15 years and, touch wood, it hasn’t affected the high-end market yet. Another popular note of doom is the rise of AI making automatically composed music, licensed for pennies. This might be a problem one day, but so far, all the algorithmically created music I’ve heard has been laughable drivel.

And, of course, library music could be wiped out by a worldwide economic collapse triggered by rogue AI, bird flu, Bitcoin hacks, a North Korean nuclear attack, an asteroid or cow farts causing runaway global warming. And you could fall under a bus, or down a manhole. However, let’s stop there, accepting that although plenty can and will go wrong, most talented library composers who beaver away making 50 tracks a year for years have big houses and nice cars, so perhaps the fear-mongering has been overstated.

Composer takeaway: Much is in the lap of the gods, but as far as rights issues go, you can turn up to PRO annual meetings or put yourself forward for a role on their committees and action groups if you feel strongly enough.

What’s The Worst That Could Happen?

To recap, the worst that could happen professionally is that you could end up bankrupt or even in prison. Pretty bad, but having the right insurance should help you avoid bankruptcy, and if you avoid stealing other people’s work and various royalty scams and bribes, you should be able to stay out of the clink too. For these risks and all the others we’ve looked at, the important thing to remember is that most pitfalls can be avoided, especially if you take the precautions in the ‘Peril Avoidance Checklist’ box.

Most composers can just get on with writing music knowing that the worst disasters are unlikely. If you spend your whole time scanning YouTube videos for piracy and rifling through your royalty reports and collection society web sites, obsessively looking for mistakes, you will indeed uncover wrongs and probably raise extra money — but there has to be a balance. If your job has become 20 percent composer and 80 percent royalty inspector, is that really what you want? Couldn’t you just let some of it go and make more money by writing more music? The answer is moderation: if you’re too lax, people will rip you off accidentally or intentionally, and if you’re too neurotic, you’ll lose money from stressing over the details instead of writing new music.

A reasonable compromise is therefore to spend a few hours every so often drilling down and trying to catch errors without letting it dominate you. Just keep writing lots of great music, and when you’re rich, hire a full-time royalty sleuth to recover your stolen millions. Until then, as Jez from Peep Show would say, perhaps you should just sign and recline — most of the time.

All About Library Music: Part 1 Getting Started

All About Library Music: Part 2 The Business

All About Library Music: Part 3 The Composer

All About Library Music: Part 4 The Client

All About Library Music: Part 5 Networking

All About Library Music: Part 6 Hollywood Trailers

All About Library Music: Part 7 How To Write Trailer Music

All About Library Music: Part 8 Avoiding Disaster

Peril Avoidance Checklist

Avoid bribes and scams. Royalty flows run into the millions, and where there are small concentrations of people handling them (publishers, royalty collection societies and TV networks), there is a susceptibility to offering ‘commissions’ and ‘ingenious business models’ that are really bribes and scams, so be wary.

Avoid bribes and scams. Royalty flows run into the millions, and where there are small concentrations of people handling them (publishers, royalty collection societies and TV networks), there is a susceptibility to offering ‘commissions’ and ‘ingenious business models’ that are really bribes and scams, so be wary.- Avoid lazy composing shortcuts. Don’t pass off other people’s work as yours, or reuse ideas in different tracks. Tune-recognition software will catch you and ruin your career.

- Get professional indemnity insurance (Errors and Omissions Insurance in the USA). Some people mistakenly think that by operating as a limited company you can remove yourself from personal legal and financial risks, but this is not true. You are personally liable for copyright infringements, and the more music you write, the greater your risk of being accused, even if the accusation is unfair. This insurance is essential for library composers: it will pay out damages to everyone affected if you are found guilty and leave your life and home intact.

- Chase the cheats. If you catch companies or composers using your music without permission, you can write take-down emails, embarrass them on social media and use the take-down services of YouTube and Facebook without any cost.

- Clarify fees and deals up front. Clients can be unrealistic or misinformed about going rates, and lowball publishers can have terrible deals up their sleeves.

- Check your performing rights organisation. Look on their music searches: are your tracks there and with the correct details? Email them and ask how they are checking that TV producers are filling in their cue sheets correctly. How co-operatively will they work with reports from Tunesat, who monitor unlicensed music usage?

- Earn money from YouTube infringement. If amateur video makers are racking up millions of views while using your music without permission, make sure you or your publisher sign up with a company like AdRev who could collect significant advertising income for you.

- Prepare for technical meltdowns. Have your plan ready, with a laptop ready to spring into action. Purchase a new Steinberg USB key every two years to stay in-warranty. Purchase Zero Downtime protection for your iLok dongle. Back up important data on a cloud service like Dropbox. Have at least two recent hard-drive back-ups, including one in a different physical location.

- Avoid bad publishers. Do your best to avoid publishers who are slow, sloppy, offer bad deals and give unhelpful music feedback.

Your Own Worst Enemy

One danger to your career is your own bad decisions. Plucked from my own litany of misdemeanours, there was the time I took on a request for news themes, but halfway through the project, lost the will to continue. I discovered that I hated news themes, with their fake urgent violas and phoney heralding horns. I quit one day with no warning, never to work for that company again. I also got into trouble early on by saying yes to every offer, and only succeeded in upsetting publishers by handing in my work painfully late.

Other bad choices some composers make include being rude or lying to publishers, not replying to their emails, making terrible music (quite a biggie!) and not listening carefully to or clarifying feedback and change requests. Be professional, know yourself, what you want to do and what you have time to do, and you won’t burn bridges like I did!

Technical Meltdowns

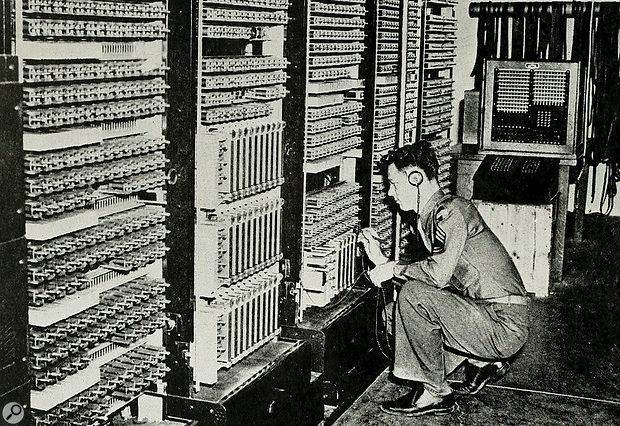

“It’s a good job I backed up the magnetic drums this morning — I’m going to have to completely reinstall Windows.”As a professional composer, library or otherwise, you have to be prepared for technical failures. Software can decide not to work, hard drives can fail, piracy prevention dongles can shut you out of your software and entire computers can die, leaving you out of action just as deadlines loom.

“It’s a good job I backed up the magnetic drums this morning — I’m going to have to completely reinstall Windows.”As a professional composer, library or otherwise, you have to be prepared for technical failures. Software can decide not to work, hard drives can fail, piracy prevention dongles can shut you out of your software and entire computers can die, leaving you out of action just as deadlines loom.

As soon as you can possibly afford it, therefore, you need a plan that will keep you running in the event of any possible fault. To cope with drive failures, you need cloud backups such as Dropbox, as well as on-site and off-site drive backups (you could lose everything in a fire, flood or theft if you keep all your backups in one place, so keep an up-to-date hard drive somewhere else!). To guard against computer failures, you need a backup of your system drive and a spare computer, such as a laptop that you can draft in at short notice to finish a job while your main workstation is being repaired. For iLok dongles, purchase Zero Downtime insurance, and with Steinberg USB keys buy a new one every two years: they are only guaranteed for two years and Steinberg may not replace a faulty one containing all your licences if it’s older than that.

Eventually these nightmare scenarios will happen to you, so you can either be sane and plan ahead, or learn the hard way from a disaster — after which time you will do all of these things anyway. Composer Marie-Anne Fischer has a typical story: “I had a disaster with my computer with all parts breaking at once whilst under pressure to meet a demanding library deadline. Apple said my computer was too old and out of support… that it was best to sell it off in parts. So, I had to invest majorly into a new computer. Having a good back-up plan is very important!”