Composer/arranger Clément Ducol (left) and engineer/producer Maxime Le Guil at work on Les Amants Parallèles.

Composer/arranger Clément Ducol (left) and engineer/producer Maxime Le Guil at work on Les Amants Parallèles.

Under the guidance of engineer and producer Maxime Le Guil, Vincent Delerm forsook grand orchestration for the humble piano — bowed, plucked and hammered...

“We had three principal constraints when making this record,” explains engineer, mixer, and co-producer Maxime Le Guil. “The first was that it was all about a love story told by Vincent Delerm from the beginning to the end. This made the lyrics and song order very important." The second constraint was that we would only use sounds coming from a piano to suggest the instruments — drums, bass, guitar, strings — and in fact, we used only the piano strings and metal frame, and not the wood. The third constraint came from the fact that Vincent is passionate about French movies from the 1950s and '60s, and he wanted the album to sound like the soundtracks of those movies, with relatively little low and high end, and all sounds in mono. Following on from this we regularly decided on several more constraints, like recording all the piano sounds using just two Coles 4038 ribbon mics, and recording everything on one Scotch 206 two-inch tape from the 1960s that I found on eBay. These constraints cleared the way for us during the making of the album.”

Parallel Lives

Despite, or perhaps because of, the self-imposed restrictions under which it was made, Vincent Delerm's fifth album, Les Amants Parallèles, is a triumph. Even for non-Francophones oblivious to the meaning of the lyrics, there's an incredibly strong atmosphere coming from the singing, poetry recitations, gorgeous melodic lines and detailed, minimalist, almost pointillist arrangements. Les Amants Parallèles typifies the unique talent the French appear to have for creating popular art that's both whimsical and deep, ethereal and substantial.

Vincent Delerm is one of France's best-known singer-songwriters and recording artists.

Vincent Delerm is one of France's best-known singer-songwriters and recording artists.

Vincent Delerm is well known in France as a singer-songwriter, pianist, composer and poet, who has released four albums since 2002. These albums contain music and lyrics in the tradition of the French chanson, with rather middle-of-the road musical arrangements. However, Delerm's art also has a more leftfield side, which tends to come out in his solo live performances. Maxime Le Guil, meanwhile, is the son of the French engineer Hervé Le Guil and his wife Isabelle, who currently run the famous La Fabrique Studios in the south of France. After an apprenticeship with Michael Brauer during 2008-9 at Electric Lady studios in New York, Maxime Le Guil went on to set up the Mix With The Masters seminars at La Fabrique (see box) and rent the former studio one space of what used to be Plus XXX studios, also called +30, which was one of France's top studios during the '80s, '90s and early '00s. Backed by a sponsor, Le Guil Jr was able to buy a full complement of analogue equipment, with pride of place going to a 72-channel SSL G-series 4000 desk that came from Olympic Studio C.

Maxime Le Guil is only 27, but has in just a few years already managed to amass some impressive credits, notably as engineer and mixer on Camille's Ilo Veyou (2011). A major success in France, Ilo Veyou got Le Guil a lot of attention and work, and Vincent Delerm was one of the artists who called him because he loved that recording. The Camille album was also made with the involvement of contemporary classical arranger Clément Ducol, whose quirky acoustic arrangements pointed the way towards the unique soundscapes of Les Amants Parallèles.

"When Vincent Delerm called me to enquire about working together, I suggested that we team up with Clément,” explains Le Guil, "and it was he who came up with the idea of doing the entire album using just pianos, which turned out to be quite a tough challenge. Vincent wanted to do something original, but his audience is quite mainstream, so the record company didn't want us to do something that was too experimental. This meant that we had to balance these two sides. Vincent also was a bit concerned that just using a piano would sound boring, so Clément and I tried to make the sounds and rhythms as exciting as possible. We brought two grand pianos and two upright pianos into my live room in Plus XXX and did a lot of experimentation with regards to creating and recording different sounds.”

Four pianos were set up at the studio, but in the event, only two were used.

Four pianos were set up at the studio, but in the event, only two were used.

The Unprepared Piano

Les Amants Parallèles was almost entirely made by Delerm, Ducoland Le Guil, with some help from two other pianists. With 15 days set aside for the recordings and 13 tracks to record, the trio were on a very tight schedule. Le Guil described their modus operandi: "Vincent had the entire story written before we began, as well as the main melodies, chords and musical structures for the pieces. He really believes in the less is more principle, so he was always shortening his lyrics and he wanted to leave lots of space for the imagination, both in his lyrics and the music. He'd record his songs just piano/vocal in the morning, playing very simple piano parts, and Clément and sometimes the pianists would spend the afternoon trying out all sorts of arrangement and sonic ideas on the piano. I would track them, and also compile individual notes of all the sounds that were created. Late at night, Clément and I would sort through everything and finalise the arrangement. When Vincent came in the next morning, we'd present him with what we'd done. He'd record his final vocal, and we might adjust things in the arrangement in response to his feedback.”

Despite the fact that the 13 miniature mosaics on Les Amants Parallèles sound both unique and entirely coherent, Le Guil stressed that they did not go in with a vision of how the end product would sound. "The recording process wasn't planned. We simply tried things out, and I recorded it into Pro Tools, which was great because we could edit and restructure as much as we liked. The only two things that were clear was that Vincent wanted this old-fashioned '50s and '60s film-score sound, and that we wanted to work with as rich a sonic palette as possible to make sure the end result would sound interesting. Another factor was that Vincent's voice has very little low and high end, so we had to make sure the music fit with his vocal, and did not overwhelm it. This meant creating a very gentle sound image and not going for big sounds. I had to really get my ego out of the way, because normally you're aiming for things to sound very impressive, but if I'd done that the vocals would have gotten lost. We would also not have remained true to what Vincent wanted.

Two main recording chains were used to capture the various piano noises: Coles 4038 ribbon mics through Neve or other preamps, and a Shure SM57 routed into a Fender Twin guitar amp miked with a Royer ribbon.

Two main recording chains were used to capture the various piano noises: Coles 4038 ribbon mics through Neve or other preamps, and a Shure SM57 routed into a Fender Twin guitar amp miked with a Royer ribbon.

"To get this old-fashioned sound, I began by recording all the music with two Coles 4038 microphones, which we ran through two Neve 1084 mic pres, the Chandler TG1 or the EAR 660. But the Coles mic sounds rather dark, so to get a brighter, more modern sound, I decided to use a Shure SM57 in addition to the Coles mics, and run the SM57 through a Little Labs Redeye 3D Phantom box that adapts the impedance of the mic so it can be plugged into a guitar amp, which in our case was a 1960s Fender Twin Reverb, with some spring reverb on it. I then recorded it with a Royer 121 ribbon mic. I was looking for more character and clarity and the Fender amp gave me that. A big part of the sound of the album comes from the SM57-Little Labs-Fender-Royer chain. I could balance the Coles and the Fender chains according to how bright I wanted the sound to be. In the end the high end of the album came from the Fender, and the warmth from the Coles. One of the Coles was close and one was further away, so I would also have the choice as to how close I wanted the sound to be. Plus XXX has a nice acoustic, so the room mic also provided some space. There's a [Neumann] KM54 in some of the pics, which I put up on the first day, but I never used it.”

I was looking for more character and clarity and the Fender amp gave me that. A big part of the sound of the album comes from the SM57-Little Labs-Fender-Royer chain. I could balance the Coles and the Fender chains according to how bright I wanted the sound to be. In the end the high end of the album came from the Fender, and the warmth from the Coles. One of the Coles was close and one was further away, so I would also have the choice as to how close I wanted the sound to be. Plus XXX has a nice acoustic, so the room mic also provided some space. There's a [Neumann] KM54 in some of the pics, which I put up on the first day, but I never used it.”

Bowing A Dead Horse

How, then, did Le Guil and Ducol manage to recreate the sounds of drums, bass, guitars, strings and other instruments using just a piano? "First of all I have to explain that we ended up using only two pianos, an upright and a grand piano. We wanted the actual piano sound to be small, and felt that the grand piano was too big sounding for the arrangements and Vincent's voice, so all the piano parts were played on the upright, with the middle pedal down, dampening the sound of the piano, and always recorded in mono. If you hear something that sounds like a stereo piano, it's two mono piano parts combined. All the other sounds were made using the grand piano. Clément Ducol demonstrates some of the techniques used to extract percussive sounds from the grand piano.

Clément Ducol demonstrates some of the techniques used to extract percussive sounds from the grand piano. For the kick drum, we used a big heavy mallet that's used in orchestras for percussion. They'd hit the frame inside of the piano with it, and I put the mics close to the strings, so I'd pick up as many harmonics as possible. Sometimes we'd put a weight on the right [ie. sustain] pedal to have all strings resonate. For the snare we usually put a piece of metal between the hammer and the string, so when the piano key was pressed, instead of it sounding like a note, it'd give a high, short sound. It was the same principle for the hi-hats. Or we'd put drawing pins in the hammers. John Cage did all these things 50 years ago!

For the kick drum, we used a big heavy mallet that's used in orchestras for percussion. They'd hit the frame inside of the piano with it, and I put the mics close to the strings, so I'd pick up as many harmonics as possible. Sometimes we'd put a weight on the right [ie. sustain] pedal to have all strings resonate. For the snare we usually put a piece of metal between the hammer and the string, so when the piano key was pressed, instead of it sounding like a note, it'd give a high, short sound. It was the same principle for the hi-hats. Or we'd put drawing pins in the hammers. John Cage did all these things 50 years ago!

"We did not use the wood of the piano, because we felt that this would be too much like traditional percussion. Clement would play the bass parts by tapping the bass strings with his fingers, and for guitar or harp-like sounds, they would pluck the piano strings. For the string-like sounds we used horsehairs from violin bows. We'd put the horsehair between the piano strings and would hold each end of the horsehair with one hand, and then move it up and down to get a sustained note. Depending on how thick we wanted the note to sound, we'd use one string or more — on the grand piano, each high note has three strings. If we wanted to record a chord, there'd be three of us doing one note each, because you'd need two hands to do one note. Horsehair was rubbed across the strings to create a 'bowed piano'. Of course, we could record the chords only one chord at a time. I also took samples of single notes of all the other sounds that were made, and as a result I ended up with tons of folders with individual notes, including flats and sharps, made by plucking and tapping and using the mallet and so on. I never built an entire part from these samples, though. I'd only use them in case Clément wanted to change or add one note in a part that had already been played and recorded.

Horsehair was rubbed across the strings to create a 'bowed piano'. Of course, we could record the chords only one chord at a time. I also took samples of single notes of all the other sounds that were made, and as a result I ended up with tons of folders with individual notes, including flats and sharps, made by plucking and tapping and using the mallet and so on. I never built an entire part from these samples, though. I'd only use them in case Clément wanted to change or add one note in a part that had already been played and recorded.

"I have to add that throughout this process we never deliberately set out to create harp or string or horn parts. It was more a matter of the musicians being around the pianos and being creative, trying things like using the eBow and horsehairs and so on. That was a fun process of trying things out that was very experimental. Getting all these sounds was all about mic placing and different techniques in playing the piano. I recorded everything into Pro Tools at 24-bit/96kHz, which was another constraint, because my rig in Paris can only handle 96 tracks at that resolution, so this prevented us from ending up with 300 tracks in a session. We sometimes ended up with 50 tracks, and when sorting and editing them in the evening, we'd always make sure we ended up with just 20 tracks, because I knew I later wanted to transfer things to analogue tape. We reduced the tracks through making choices and deleting. Given that we only had 15 days for the recordings, there was no point in pushing back choices.

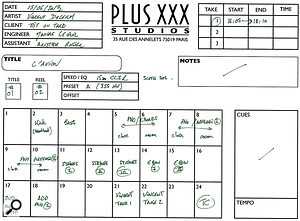

A typical mix track sheet, from the song 'L'Avion'.

A typical mix track sheet, from the song 'L'Avion'. "When Vincent came in the next day, we'd record his vocals with a Neumann U47 going into a 1084. We used the same signal chain on the two female voices. One was Vincent's wife, who recorded what was meant to be a scratch vocal when we were doing rough mixes for the label, but Vincent liked it, so we kept it. He works from his feelings! The other female vocal was spoken by Rosemary Standley of the band Moriarty. There was a bit of coaching involved in recording Vincent's vocals. Clément and I also worked on this together — we co-produced the album. We tried to record vocals every day during the recording process, again because we knew we only had 15 days, but on the last day Vincent said, 'You know what? Play me the entire record.' So he re-sang all his vocals, doing two takes per song, and these became the final vocals that appear on the record. Basically, all his vocals were laid down in one three-hour session, after all the arrangements had been done. I think the entire recording and arrangement process helped him realise how he wanted to deliver his songs. At some point it clicked in his mind, and he was ready to perform.”

Scotch Rocks

After the recordings were complete, Le Guil took nine days to mix the entire project. His first step involved bouncing everything to some very obscure analogue tape. The ultimate in tape? A single reel of Scotch 206 was used for all the mixes. "Producer David Kahne told me one day, 'You don't know what tape is until you've heard Scotch 206 tape from the '60s,' and I was lucky to find one two-inch reel on eBay. This became another constraint. Once the recording process was completed and we had made all our choices, I transferred all the songs to that tape, which dated from 1960 or so, using my Studer 24-track. The tape was in good condition, we didn't have to bake it, and I just had the one reel, which meant that I had to delete some of the songs after mixing, and record others to the same reel. I recorded everything at 15ips, without noise reduction, because I wanted that old sound, which is why the record is a bit noisy. I have to admit that I never compared the Scotch tape to other tapes that I have, like the ATR and GP9. I didn't want to have that option. We simply decided that we wanted to do it like that.

The ultimate in tape? A single reel of Scotch 206 was used for all the mixes. "Producer David Kahne told me one day, 'You don't know what tape is until you've heard Scotch 206 tape from the '60s,' and I was lucky to find one two-inch reel on eBay. This became another constraint. Once the recording process was completed and we had made all our choices, I transferred all the songs to that tape, which dated from 1960 or so, using my Studer 24-track. The tape was in good condition, we didn't have to bake it, and I just had the one reel, which meant that I had to delete some of the songs after mixing, and record others to the same reel. I recorded everything at 15ips, without noise reduction, because I wanted that old sound, which is why the record is a bit noisy. I have to admit that I never compared the Scotch tape to other tapes that I have, like the ATR and GP9. I didn't want to have that option. We simply decided that we wanted to do it like that.

"For the mix I laid the 20 tracks out over my SSL desk, and to avoid its modern sound, I ended up mixing through the monitor path and not through the channels, and with the desk in record mode. When you use record mode, you bypass most of the electronics in the desk, including the line amp and so on. The mix process itself was very simple. I didn't do anything too fancy. Again, we wanted it to have this '60s sound, so I used an old RCA BA6A [compressor] on Vincent's vocals as well as parallel compression from an [Urei] 1176, and I again used my Neve 1084 to warm up the vocal sound. I used two compressors on his voice, with quite heavy compression on the 1176 to bring out more tone, because he has a very soft way of singing without much presence. I also had the AKG BX15 spring reverb on his vocals, coming from from an Altiverb plug-in in Pro Tools. I applied quite a lot of processing on the bass and bass drum, because honestly, if you put a mic inside of a piano and you hit the frame it sounds terrible. But we had decided on the concept so I had to make it work, and I used an Electro-Harmonix Polyphonic Octave Generator pedal or the Eventide H3000 as pitch-shifters on the bass and kick drum, to give me a lower octave on the kick drum and bass. I didn't do much to the rest of the parts, I mainly just added some spring reverb.

"One important thing that I did during the mix was a lot of riding levels. It was already quite a challenge to make sure that using just one instrument didn't sound boring, but on top it was very hard for the players to bring expression into the parts. A string player will give you many dynamics, but this was difficult to do when using the horsehairs or mallets. So to add dynamics and expression I had already done many level rides in Pro Tools, and I enhanced this even more during the mix, using the SSL automation. I also mainly used LCR [ie. hard left, right or centre] panning, again for this '60s sound. We mixed back to Pro Tools and an ATR 102 two-track with half-inch RMG modern tape, but we ended up liking the digital version better. We'd already had Coles mics and vintage mic pres and old tape from 1960 at 15ips, so everything was already very creamy and warm-sounding, and we needed a bit of modern brightness.

"The record company, Tôt Ou Tard, trusted us during the recording and mixing process, so we were a bit concerned that this might be too experimental for them. Also, it was only during mixing that we realised that many songs are very short, and that the entire album is only 35 minutes long. But it was again a case of less is more. Vincent loves the album, and so does the record company! They feel that it's a very good move for Vincent, because he's mostly known for his lyrics, and this time he's offering something new on the music side. They love the emotion of the record. There have been some press presentations, and the press loves it as well, so we're all very excited about the upcoming release!”

Mix With The Masters

Outside France, Maxime Le Guil is perhaps best known for creating the Mix With The Masters residential mixing courses together with Victor Lévy-Lasne. Mix With The Masters has been running since 2010, and has allowed students to learn first-hand from many of the world's top mixers and producers, including Michael Brauer, Manny Marroquin, David Kahne, Al Schmitt, Eddie Kramer, Chris Lord-Alge, Tom Elmhirst and many others. What makes the MWTM classes unique is the fact that they take place in idyllic seclusion at La Fabrique Studios in Provence, with only 15 carefully screened participants per class. The atmosphere is striking, and both participants and teachers have called it "a life-changing experience”.

Le Guil explains how they came into being and what makes them different. "I had the idea initially purely for selfish reasons. I'd had such a good time being an intern at Electric Lady in New York, working with Michael Brauer, that I wanted to work with him again. For all sorts of reasons I could not go back to the US at the time, so I thought about how I could fly him over to France for a week. I partnered with an old school friend, Victor Lévy-Lasne, because I wanted someone to handle the business and logistical side of things, and we made a budget for how many people we'd need to cover the cost of a studio and Michael's fee, and thought of La Fabrique, because my parents run it and because the control room can easily hold 15 people or more. It also seemed to make sense to run the class in a residential place, rather than have people stay in hotels. There was no way we could afford to pay Michael his regular fee, so we offered him and his family an extended stay at La Fabrique, because it's a great place for a holiday.

Michael Brauer shares his skills with a select group in a Mix With The Masters seminar."We're still very grateful for the fact that Michael trusted us and was up for doing this, and we planned two one-week classes in August 2010, the first with David Kahne, then a week's break and then a second class with Michael alone. Michael, Victor and I spent a long time designing the basic teaching template for these first two weeks. The classes in 2010 were supposed to be one-off events, but the reactions were so strong, with people crying when they left and saying it had been the best week of their lives,that we suggested to Michael that we could do it again the next year. When Michael and David returned to New York, they spoke with other top mixers about it, saying it's awesome. Several more mixers were also up for doing it, so we could expand and run more classes in 2011. Next year we aim to run 16 seminars. We are very careful not to grow too fast, and not to lose the spirit.

Michael Brauer shares his skills with a select group in a Mix With The Masters seminar."We're still very grateful for the fact that Michael trusted us and was up for doing this, and we planned two one-week classes in August 2010, the first with David Kahne, then a week's break and then a second class with Michael alone. Michael, Victor and I spent a long time designing the basic teaching template for these first two weeks. The classes in 2010 were supposed to be one-off events, but the reactions were so strong, with people crying when they left and saying it had been the best week of their lives,that we suggested to Michael that we could do it again the next year. When Michael and David returned to New York, they spoke with other top mixers about it, saying it's awesome. Several more mixers were also up for doing it, so we could expand and run more classes in 2011. Next year we aim to run 16 seminars. We are very careful not to grow too fast, and not to lose the spirit.

"We had no idea when we did the first classes with Michael and also David that they would have this effect on people. I think a large part of it is the fact that everyone spends a whole week together in the same place, so there's a week of having breakfast, lunch and dinner together in a beautiful place, and people bonding and supporting each other. The guest speakers always are incredibly grateful for coming, because it forces them out of their studio and the pressure of their daily lives. Being at La Fabrique is very different, even though it also is a studio. Many of these mixers and producers spend most of their lives working in the shadows, and this is their moment in the limelight, while they at the same time can share and give back what they have learnt. They often learn from the participants as well, who tend to be a bit younger and who are all Pro Tools wizards. It's not about the guest speakers lecturing the participants, it's a shared experience for everyone, 18 hours a day for seven days.

"Michael told us for the first seminar that he wanted people with plenty of experience — people 'who have lived it' was the phrase he used. There's no point in these top guys teaching beginners. So we spend quite a bit of time screening applicants,and making sure they have five to 10 years of experience and come for the right reasons and with the right attitude. We've had participants who are already very successful, and people who hit a brick wall in their careers, and who don't know how to get to the next level. They're all looking for technical insights, career and business insights, guidance on how to run sessions, psychological and philosophical insights and inspiration, and so on. We want every seminar to be 100 percent successful, and so far we have managed that. There are people who have done several seminars. One guy came back nine times!”