Producer Phil Ramone was legendary for getting great vocal sounds. Here's how he did it — and how you can do the same.

Creating a spectacular vocal sound is central to any great recording. The question is, how do you do it? Countless producers and engineers have worried about this, ever since Edison first put a needle into a piece of tinfoil. Personally, I've been on a search for an answer to this question for almost 40 years.

Little did I realise it at the time, but I got a central clue when, in 1977, I overheard a conversation between the executives at Columbia Records, expressing their worry about an artist of theirs named Billy Joel. They believed that he had the potential to be huge, but for some reason, up until that point, he'd only had minor success with the 1973 song 'Piano Man', and had subsequently floundered. They came up with what they thought would be a solution. They were convinced that if they could get Phil Ramone to engineer and produce Billy, he would break through.

Producer Phil Ramone was famed for his ability to coax great vocal performances from his artists. Although he started out as an engineer, he was not particularly interested in the tools of recording. He believed that he would get the best sound by making the cumbersome recording process invisible. He strove, in every way, to get his artists to forget that they were in a recording studio.

Producer Phil Ramone was famed for his ability to coax great vocal performances from his artists. Although he started out as an engineer, he was not particularly interested in the tools of recording. He believed that he would get the best sound by making the cumbersome recording process invisible. He strove, in every way, to get his artists to forget that they were in a recording studio.

The Columbia guys saw what Ramone had been able to do producing Phoebe Snow, who was an unknown artist with little chance of success when Ramone discovered her. I was there when he raised this 22-year-old up from obscurity to produce two hit albums with her, including her smash 'Poetry Man'. They also liked what Ramone had done in his 1975 collaboration with Paul Simon, Still Crazy After All These Years. This number one album, which I also got to participate in, was a huge hit, yielding four singles, including '50 Ways To Leave Your Lover' and winning the Grammy for Album of the Year.

During that conversation, I remember one guy, with a combover, big glasses and a satin baseball jacket, saying, "I don't know how he does it, but the guy gets the most incredible sound on these guys' voices. It's friggin' magic.”

Ramone's Recipe

The execs were right, both about Billy, and Ramone. Starting with the album, The Stranger, and then continuing over the next nine years, Billy Joel sold over 150 million records, becoming the third biggest selling artist of all time. The recently departed Phil Ramone, a winner of a lifetime-achievement Grammy, has been feted as one of the seminal figures of the pop music era.

What contribution did Ramone make that turned this second-tier artist into a multi-platinum superstar? What was the magic that allowed him to get that incredible vocal sound? The secret to Ramone's success in both production and sound is the same. After all, he was a star both as producer, with Simon and Joel among countless others, and as an engineer, where he got great vocal sounds on innumerable singers from Streisand to Sinatra. If you learn his one special technique, it will not only help you get the best recorded sound, it will also give you the key to producing a great recording.

How was I lucky enough to witness this master's wizardry? Phil started me on my own quest for the holy grail of transcendent sound when I was apprenticed to him at his A&R Studios throughout the 1970s. In my time there, I not only got to work with Simon and Snow, but some of the other great vocal luminaries of our time, including Sinatra, Dylan, Jagger, Karen Carpenter, Ray Charles and Judy Collins. Ramone, and sometimes I, was responsible for getting an unforgettable, hit sound on all of the above.

After a wonderful 20-plus-year career in the biz, I continued my study of the question of how to help to make a singer sound great from a different angle, when I reinvented myself, in the early '90s, as a psychotherapist and artist's coach. With that combination of music and psychology, I was able to pinpoint the means of achieving a great vocal sound, both from observing the intuitive master Ramone, and from researching the neurobiological theory that backs up, and gives a scientific basis for, what Ramone knew in his gut.

Get The Gear Out Of The Way

Of course, gear is important for sound. A warm, luscious microphone that fits your artist's vocal timbre like a custom suit, a huge-sounding and super-clean preamp, a dynamite compressor that makes the vocal stick in the middle of the listener's head no matter how deep the vocal is tucked in the mix, and the latest, indispensible effects plug-in are all great to have. Some of them may even be necessary, but none of them is the core element. Anyone can buy that stuff. It is something far more ineffable that is going to make the sound of your star's vocal rise up above all the competing noise, and find a special home in your audience's heart.

Billy Joel was one of many artists whose career took off when he worked with Phil Ramone.Photo: Richie Aaron / Redferns

Billy Joel was one of many artists whose career took off when he worked with Phil Ramone.Photo: Richie Aaron / Redferns

What I'm about to say should give hope to all of you out there who yearn to do great things but are not musical geniuses. From what I saw, Ramone's monster success with Billy, and the sound he was able to get on all the artists he worked with, was not based on his talent, musical skill, technological prowess, or the equipment he owned. Rather, his magic came from his keen understanding of the emotional side of creating music.

This leads us to the one-word answer. The key to getting a great vocal sound is about what happens between the producer and the artist. It is all about relationship.

The surprising truth is that the technology is not the key to great sound; it is the impediment to it. Considering that Phil Ramone started out as an engineer, and didn't really become a producer in his own right until he had been a recordist for close on 15 years, you might find it strange to learn that he was not particularly interested in the tools of recording. If he was always searching for innovative recording machinery, it was in the service of making the recording process as transparent as possible. He believed that he would get the best sound by making the cumbersome recording process invisible. He strove, in every way, to get his artists to forget that they were in a recording studio.

As an engineer, his approach proved a winning one, beginning with his first hit single, 'The Girl From Ipanema', for which he won an engineering Grammy in 1965. He recorded this song in minutes, with minimal miking. The entire album was done in a matter of days. Astrid Gilberto's vocal, in what became known as the characteristic Bossa Nova style, was singular for its languid, sexy quality. It was Phil's talent to make this novice singer so relaxed that she was able to sound great.

How did he do it? I was initiated into the Ramone method from my first day interning at his studio. I learned these principles, and have lived by them, from that beginning to this day, and have passed on this wisdom to the many people I trained and coached through the years, carrying on the Ramone legacy through the generations.

Become A Yes Man

I was given the first lesson by the studio manager, Nick DiMinno. He stuck his nose next to mine and said, "Whatever the artist asks, your only answer is yes. Do you understand?”

Taking in that first directive, I answered, appropriately, "Yes.”

DiMinno learned the lessons well himself, and went on to be a terrifically successful jingle producer who is still making it in the business all these decades later.

Saying yes seemed simple enough, but it took years for me to understand that this command went to the heart of Ramone's approach. We never said no, because our main job was to make the artists feel absolutely safe and comfortable, so they could give their creativity free rein. Our goal was to create the conditions where they would feel no inhibition whatsoever about expressing themselves. Their wish was our command. It turned out that always saying yes was also a great way to get ahead in the business. It is a good way to approach any goal you might have.

Everyone on the A&R staff lived by that code. But the second aspect of Phil's magic was something that he did in a way that no one else could match, and this, I believe, was central to his success. Phil had a way of making the artists he worked with feel brilliant. He was the perfect champion of their artistic aspirations.

Of course, every artist dreams of doing amazing work, but they are also consumed by doubts. Even Dylan, with whom Phil and I worked on Blood On The Tracks, would call, almost weekly, after the album was done, to ask Phil if he thought what he had done was any good!

By making the artist feel beyond special, Phil was able to evaporate the doubts which could inhibit their best performance. Phil made certain that the artists he worked with not only lived in the ideal playpen, where they had permission to give free rein to their imaginations, but they also were made to feel that everything they created was gold. Simply put, the way Ramone got the best songs and performances out of the stars he worked with was to prize the artist and keep the technology invisible. And, for our purposes, it was the way he was able to get the best recorded vocal sound.

Lessons From Lizards

But why was that the case? Why do artists give better performances when they are made to feel special? Now this is where my later training as a psychotherapist comes in. In order to grasp this, it is important to understand a little bit about how the brain works. The amygdala.

The amygdala.

In my field, there has been a great deal of interest in a part of the brain called the amygdala. The amygdala is tiny, about the size of walnut, and is pretty much in the centre of our brain. This part of the brain regulates our response to danger. The amygdala is a very old part of the brain, and one that developed long before the new, human, part of the brain, the neo-cortex, came into existence. It can be found in all vertebrates, including reptiles. It was probably in dinosaurs.

So, though this isn't completely accurate, let's think of the walnut as the reptile brain. Reptiles don't understand English. They don't know about past, present or future. They don't learn in very complex ways. They don't have perspective, wisdom or imagination. They can't conceive of anything that isn't before their eyes. They certainly have never produced a Top 40 hit. Basically, they sit on a rock, scanning the horizon for danger, and occasionally stick out their tongue to eat a bug.

What does the amygdala do? When we perceive ourselves to be in danger, the amygdala gets activated. This turns on what we call a 'sympathetic response' in the autonomic nervous system. This is what we know of as the 'fight, flight, freeze' system. Our hands get clammy, our hearts pound, our genitals retreat into our body (no time for sex when you are being chased by a mastodon!) and perhaps most importantly for the singer, our throats tighten and our mouths get dry.

When our amygdala is on full throttle, the different parts of the brain stop acting in concert. To oversimplify, the connection between the reptile and the human parts of the brain get unplugged. The different parts of the brain stop communicating effectively with each other. The reptile takes over. We can't think straight, our perspective gets very narrow, and we basically feel anxious, or afraid. We certainly can't be creative.

The Emptiness Inside

What does the amygdala have to do with getting a good vocal sound, or for that matter, making a great recording? To understand this, we need to know what kinds of events we perceive to be dangerous. In our modern lives, the dangers we face rarely come physically from the natural world. It is safe to assume that when you go home tonight you will not encounter a sabre-tooth tiger. The great fear that most of us suffer, especially the sensitive artists among us who make our living by exposing our hidden depths, is the fear of shame.

What is shame? It is the feeling that goes along with the belief that there is something fundamentally flawed about you. Somehow, you don't measure up as a human being. Now you'd be surprised to think that the egomaniacs who often populate the world of pop celebrity would be subject to feelings of shame, but this is, in fact, an inverse rule. The more a person needs an unending supply of approval from larger and larger numbers of people, the more they are working double overtime to compensate for a profound sense of inner emptiness. And right in the middle of that emptiness is that terrible feeling of not belonging that is central to shame. This is a pretty good definition of what we popularly call narcissism.

Though they may project the appearance of a massive ego, the vast majority of creative people are also sensitive people. That means they are the most susceptible to having their feelings hurt, which means they are vulnerable to being shamed. This is a terrible irony, since artists put themselves in a position where they are most likely to be humiliated, by exposing themselves in such a naked way through their creation, and by singing. This is a paradox and conflict that many artists live through. As the great, late director/choreographer Bob Fosse put it to me, "I have total self-confidence, and total self-doubt.”

What provokes the bad feelings associated with shame? Most often, it is the experience that we are being rejected, misunderstood or put down. Depending on our sensitivities and past hurts, the bad feelings we get when we are shamed in the above ways can be devastating. In fact, these feelings are what we often dread most in the world. When we go through particularly bad emotional woundings, especially earlier in life, they make an almost permanent impression on the brain. With each repeated painful experience, we become increasingly susceptible to that reptile brain getting triggered. Then, when we merely anticipate that we are going to be in danger of being shamed, the walnut takes over, and we go into our fight-flight-freeze reaction. We say that this fear response has become conditioned.

Any choice of vocal mic will always be secondary to the singer's performance.

Any choice of vocal mic will always be secondary to the singer's performance.

Creating A Safe Place

So, here's what happens. Your artist is about to do a vocal. As they prepare to expose themselves in the most vulnerable way, this triggers an automatic fear response. Outside of their awareness, they are anxious that they will be rejected or put down. That is, they are afraid that they will end up feeling the pain of shame. As every artist has experienced these kinds of humiliations, this reaction is now conditioned. This means that the sympathetic nervous system gets activated just by the thought that they are going to have to sing in front of a microphone.

This leads to a typical scene that I have witnessed innumerable times in the studio, and you've probably seen as well. The singer comes in to overdub the lead vocal, rubbing her throat. She says, "I just don't think I have it today. We might just have to cancel the session.”

All the reasoning in the world doesn't seem to work. Now we have to deal with what we have characteristically called the "temperamental artist”. No technology that has been invented so far has been able to change that. What we are seeing is that the reptile brain has taken over, so the person no longer understands English. What do you do?

We need to convince the nervous system of our singer that they are in absolutely no danger, whatsoever. If we can do that, the walnut will stop glowing. Our amygdala will calm down, and go off-line. The neo-cortex will light up again. If we can do this, another part of the autonomic nervous system kicks in. This is called the parasympathetic system. This is the body's 'all clear' signal. Our breathing deepens and slows. Our throats open, and we lubricate. We can focus. In the best cases, we flow. Time expands, and we become totally immersed in the present moment. We feel like singing!

One indispensible way to make the brain, and our nervous systems, operate in a way that is optimal for creativity is for us to feel safe. What actually happens when we are in this state is that all of the different sections of the brain start vibrating in harmony. Have you heard of alpha, or beta brain waves? What this is referring to is that each section of the brain vibrates optimally at its own, particular frequency. There is a section of the brain, that when it is doing its job, regulates all of these different vibrations so that the brain can operate as a single unit. This is the conductor of the neuronal orchestra. This part of the brain vibrates at 40Hz. So yes, the brain itself is musical!

Stage & Studio

But, you might ask, why, then, do singers sound the best when they are on stage? Isn't that an incredibly stressful situation? Wouldn't their reptile brains be turned on then? Wouldn't that situation ruin their vocals instead of making them better?

Creativity happens in the highest, most advanced, most human, centres of our brains. In order to create, we need the imaginative part of the brain to be working optimally. We need the clearest communication between all the different parts of the brain, including all the emotional centres and the intellectual centres. In order for this to happen we need to be in the optimal state of arousal. Yes, a certain amount of adrenaline, one of the main hormones that is pumped into our system when the amygdala is activated, actually improves our performance. And as long as the amygdala is communicating well with the other parts of the brain, it can help us sound better. But research has repeatedly proved the Yerkes-Dodson law, which is that once the arousal goes beyond a certain point, performance goes down. Once the reptile takes over, all you can do is hiss.

Now, how do you make a person "optimally aroused”? This is where Phil knew what he was doing, though he knew nothing about neurobiology. In order to make a person come down from debilitating anxiety, we need to find the antidote to the fear of shame that over-activates the amygdala. We also need to find the right stimulants to excite the person in just the right way. The answers, as the great psychologist Carl Rogers discovered, are:

- Unconditional positive regard

- Mirroring

- Validation

- Prizing

Let's break down the four components of interaction between the producer and artist that promote the likelihood of this optimal state.

This first step in priming the artist's nervous system is unconditional positive regard. Here, the artist becomes secure that no matter what they do, they will not be negatively judged, and their producer will continue to love them. They know that they are in no danger of being shamed or abandoned. You see, the experience of shame and abandonment are very closely linked. It is when we have the experience that our bond of connection is broken with someone that we feel the torment of shame. The artist must feel certain of the relationship with their producer in order to reveal themselves in the absolute way that the greatest performances demand. Ramone's loyalty to his premiere artists was absolute. He went so far to name one of his kids Simon Quincy (he was also very close to Quincy Jones), and the other one William Joel!

Sometimes, this loyalty was sorely tested. No matter how difficult a demanding artist like Paul Simon could be, with projects going on for years, Ramone always stood at his side. He followed him into the breach, and was willing to suffer any pain in the service of Paul's artistic vision.

The next relationship dynamic that is necessary for the singer to feel open is to be mirrored. Ramone perfectly understood the sensibility and needs of the artist. Ramone 'saw' Billy Joel in a way that no one else did. Ramone reflected back what Billy wanted, and was able to articulate this vision in ways that helped Billy clarify his vision. For example, Billy's previous producers wanted him to work with top studio musicians, thinking that would get the best tracks. But Billy wanted to work with a local band, something that would sound less generic and more individual. He wanted to work with people he felt connected to. Ramone got this, and totally embraced the idea.

On stage, a singer can rely on the acclaim of the audience. It's the producer's job to fulfil that role in the studio.Photo: Søren Gammelmark for Aarhus Festuge

On stage, a singer can rely on the acclaim of the audience. It's the producer's job to fulfil that role in the studio.Photo: Søren Gammelmark for Aarhus FestugeThis ability to mirror the artist was why Ramone's tracks did not have a signature sound. His thing was not to bend an artist to his vision or will, but to recognise and mirror the vision of the artist. Billy's work became so strong, and he became such a star, because it was so vivid and singular. The clearer the vision, the more powerful the impact. The more individual the expression, the more universal the art. If the artist believes that their producer is truly there for them, and understands them, this will engender a bond of trust. These are the basic, necessary conditions in the brain for the experience of safety and security that calms the amygdala.

Validation

Now, to promote the optimal arousal, the next step is validation. That is where the producer affirms the viewpoint and perspective of the artist. The producer not only reflects what the vision is, but 'gets it'. That is, they fully comprehend what the artist is trying to say, see the value or truth in that vision, and help them realise it.

I saw how this method worked with Phoebe Snow. In trying to make her first record, she had wasted a year, and her entire budget, unable to get anything on tape. The producer from her label, Dino Airali, with only the smallest amount of money left, came to Phil in a last-ditch attempt to save the project.

Ramone agreed to participate. He said to Phoebe, "Tell me your dreams. If you could have anyone in the world play on this record, who would it be?” Then, when she told him, Ramone not only understood her choices, and celebrated them: he actually got the musicians she dreamed of having! This freed up Phoebe's creativity, and Phoebe's vocals just flowed out of her. She sang her ass off. And one reason that first record of Phoebe's is stellar is because of the blend of unique talents who played on it, like pianist Teddy Wilson, saxophonist Zoot Sims and percussionist Ralph MacDonald. Phil authentically believed in Billy Joel and Phoebe Snow, and the choices they made. That's why, in an ideal world, a producer should only work with an artist that he or she genuinely respects and admires.

Part of being able to validate the artist's vision is being able to perceive quality before anyone else can. There was more than one occasion when I couldn't see the value in a particular artist and their creations, but Ramone could. He had an uncanny ability to predict the hits. He would see the brilliance in the artist, and their songs, before anyone else. This happened with a song called 'Afternoon Delight'. I thought it was a turkey headed right for the $1.99 bin. Ramone heard the hit, added the song's hook, which was a flanged pedal-steel guitar, and it became one of the biggest singles of the decade.

The final component for achieving optimal arousal is prizing. Phil Ramone not only showed absolute deference to the artist, but did everything he could to make them feel like a genius. Ramone was the ultimate audience of one. Without being sycophantic, and, in fact, while having the most discerning ear, he was the artist's biggest appreciator and fan.

Remember that question of how could it be that an artist can sing well on stage? Well, first of all, we know that many artists suffer terrible stage fright and have the worst time getting out on stage in the first place. But when they do, if they receive the accolades of the audience, this is the ultimate turn-on.There's nothing like the prizing of an arena full of 50,000 fans screaming with adoration to keep your excitement levels primed. I'm sure that's what keeps Mick Jagger swaggering after all these years.

But just as the fear of public humiliation that would come from rejection poses its own kind of nightmare, the studio poses another. Playback and the solo button are not the singer's friends. The kind of self-scrutiny that studio production requires can send that reptile into a frill-expanding terror.

The prizing of the producer is the cure for that fear. Nothing feels as good as when someone you trust and love is certain that who you are, and what you are doing, is great. When the singer feels that they are absolutely protected by their producer, that they can do no wrong, and they will never be harshly criticised, misunderstood or shamed; when they believe that their producer will always be there for them, understands who they are, sees their unique value, and loves what they make; not only are a singer's vocal mechanics optimised, but the conditions are created for the emergence of the more ephemeral qualities of confidence, excitement, focus, flow, spontaneity and creative imagination that all contribute to the innovation and unique expression that has led to our greatest musical recordings.

Acceptance & Development

Now that is all well and good, but what if the producer has something critical to say? What if the producer needs to prod the artist to go further? What if the producer wants to suggest a different direction? How can they do this and maintain this delicate realm of absolute safety and optimal arousal?

Remember, when the amygdala is turned on, and the neo-cortex is turned off, the person does not understand the human language. Not only are we incapable of creating when we are like that, we are also incapable of learning, or taking in new information. When an artist is in that state, they are not going to be receptive to the producer's suggestions.

But if the producer has done all that they can to create these conditions of safety, and the neo-cortex comes back online, the artist will then be willing to hear, and be receptive to, the producer's contributions. They will be able to take in suggestions without feeling bruised or shamed. Paradoxically, it is only when the artist feels completely accepted as they are that they are willing to grow and change. The producer should never want to 'change' the artist, anyway; any criticism must be constructive in the sense that all suggestions are meant to help the artist realise his or her own vision, to become more of who, and what, they already truly are.

How can a producer learn to provide all of these things to their artists? Ramone was a master at the emotional side of music production because he had been a highly sensitive artist himself. He had started out as a violin prodigy. He could relate to, or empathise with, the plight of the artist, because he had experienced this pain himself. This ability to empathise is key in being able to give artists what they need for optimal sound production and creation.

Michael Jackson: another stellar talent who required unconditional regard from his producers.

Michael Jackson: another stellar talent who required unconditional regard from his producers.In order to foster that empathy, and be able to maintain a state of openness, willingness and receptivity, the producer needs to keep his own amygdala on an even keel. The producer needs to have a kind of emotional resilience where he or she does not get overcome by shame, undermining the connection with their star. If a producer interprets an artist's demands as attacks, he or she will respond defensively, rather than in a nurturing way. To put this another way, the producer needs to be as 'egoless' as possible.

An example of what is required, psychologically, of the producer, can be observed in the Michael Jackson film This Is It.In one highly revealing scene, Michael is unhappy with his headphone mix, and goes into an incomprehensible, almost psychotic rant, attacking the director and choreographer, Kenny Ortega. By the time Ortega took this gig, he was already phenomenally successful, and certainly did not have to tolerate the kind of abuse that Jackson was heaping on him. But Ortega remained cool. Ortega was able to interpret Jackson's reptilian gibberish, figured out what Michael wanted, reflected this back to him, validated this need, and fulfilled it for him, without manifesting even a scintilla of edge. He was completely there for his artist. He was clearly secure enough within himself to not take this personally. When Ortega stayed calm himself, and was then able to be there for Michael, the artist immediately calmed down, and was able to sing and perform again.

Stay Together

What this means is that in order to get the best sound, you need to cultivate your own emotional health. We certainly know there are producers who are not paragons of stability. There are cases where producers get all of their sense of self and validity from sacrificing their own needs and identity to others. There are also producers who use artists merely as objects to realise their own grandiose visions. There is no denying that both of these approaches can lead to certain kinds of success. But it is also true that they can lead to trouble. In the former, the producer probably isn't very happy. This kind of person is always desperate for another's approval, but inside is seething with resentment, which will eventually take its toll. Drug and alcohol abuse has always been rampant enough in music for us to recognise the kinds of danger that can be fueled by this kind of self-sacrifice. For the latter, the excesses of control of others can lead to truly monumental problems. The most striking example of this is Phil Spector, who produced some amazing records, but was known as a pathological control freak and today finds himself in jail for murder. Both of these approaches — victimhood, or dictatorial control — are dysfunctional. The name we use for them in my business is 'codependent'.

Though you might achieve success in these ways, the question is: what kind of person do you want to be on your road to stardom? Do you want to be a doormat, or be someone of integrity? Do you want to make it by being crazy, or do you want to be the best you can be, both inside and out? The answer to these questions may not determine your short-term success, but I contend that it will make or break your staying power. The guru and therapist, Baba Ram Dass, said that the best way therapists can help their clients is by continuously developing themselves as people. I am going to contend that the work of a producer is the same. The more evolved you are, and continue to become, the more able you will be to form the kinds of relationships with artists that will lead to the best-sounding vocals. Not only will your emotional maturation lead to the sound of your recording being the best, but it will also deepen your artist's creative expression in general.

The key thing those executives knew, and I overheard, was this. They didn't recommend that Billy Joel work at a particular studio, or record on this or that console, or use a particular microphone. They recognised that the answer was him working with the best person. The friggin' magic didn't come from equipment, it came from the magician. Great sound doesn't come from the gear; it comes from the artist's body. The best way to get that sound out of your singer's inner equipment is through the love you have to give them.

By cultivating yourself, you will be able to form a bond with your artist based on unconditional positive regard, mirroring, validation and prizing. Then, you will not only have what it takes to produce the most amazing-sounding vocals, but you will be able to create timeless music that will make the world a better place to listen to.

Things You Should Never Say To Your Artist

If anyone embodied the contradictions of the pain and glory of fame, fortune, art and the music biz, it was Karen Carpenter. Though she was blessed with an uncanny voice, and the ability to make millions of fans buy her middle-of-the-road records, she lived a life of profound hidden agony. Wealthy and adored beyond all measure, she was actually lonely and empty. She suffered from anorexia nervosa, a terrible eating disorder.  Karen Carpenter's only solo album was shelved after negative reactions from record company executives — and Paul Simon. It finally saw the light of day in 1996, 13 years after the singer's death.

Karen Carpenter's only solo album was shelved after negative reactions from record company executives — and Paul Simon. It finally saw the light of day in 1996, 13 years after the singer's death.

I engineered some of Karen's first, and only, solo album. It was easy to see just how lost she was. Up until that point, she had made her records in the protective company of her brother, Richard. But he too was struggling, trying to recover from a Quaalude habit. Karen came to New York, looking for guidance, and ended up in the hands of Ramone.

In the middle of the project, Paul Simon came in to hear the new material she was working on. It was obvious to anyone who came into contact with her that she was in an extremely fragile emotional state, and was starving herself to death. But this did not stop Paul from speaking his mind. After listening to the songs, he said, "Karen! What are you doing? This stuff is awful! This isn't what your fans want from you! This will ruin your career!”

He may have had a point, but he had no sense of, or care for, how this would impact on her. What Paul said devastated her. The album was shelved. She never recovered from her illness, and died at 32.

Things You Should Always Say To Your Artist

In the late 1980s, I worked with Paul Shaffer, of David Letterman fame,on a song called 'What Is Soul', for his Coast To Coast album. I had known Shaffer since our earliest days in the biz, when we both worked on the soundtrack of a Broadway musical called The Magic Show. The concept for the album was that Shaffer would collaborate with musical greats from across America, with each track capturing a historic, regional style.

Shaffer's idea for this track was to reassemble the Soul Clan. In the 1960s, Atlantic Records was making the hottest R&B records in the nation. A group of the extraordinary singing and writing talents from that label came together in 1968 and cut one single. Circumstances led to the almost immediate dissolution of this holy grail of supergroups. Aficionados of soul tried for decades to reunite these players.

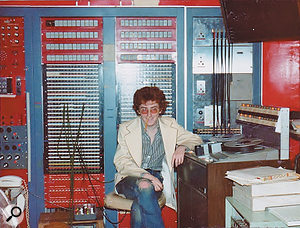

Shaffer almost managed to do it for this record, bringing together the original surviving members: Don Covay, who wrote Aretha's immortal funk hit, 'Chain Of Fools'; Ben E. King, of 'Stand By Me' fame; Wilson Pickett, who performed such seminal hits like 'Mustang Sally' and 'In The Midnight Hour' and Bobby Womack, who wrote the first hit by the Rolling Stones, 'It's All Over Now' and As an engineer at A&R Studios in New York, the author (shown then, left, and now) worked extensively with Phil Ramone and the many artists he produced throughout the '70s.Photo: Brad Davis and Joshua Silk played guitar on many of Aretha's early hits. (All that was missing was Solomon Burke, but that's another story; Otis Redding, who sang 'Dock Of The Bay', and Joe Tex, of 'Skinny Legs And All' fame, were dead.)

As an engineer at A&R Studios in New York, the author (shown then, left, and now) worked extensively with Phil Ramone and the many artists he produced throughout the '70s.Photo: Brad Davis and Joshua Silk played guitar on many of Aretha's early hits. (All that was missing was Solomon Burke, but that's another story; Otis Redding, who sang 'Dock Of The Bay', and Joe Tex, of 'Skinny Legs And All' fame, were dead.)

Shaffer co-wrote the song with Covay, and, to add even more superstar power to the track, the god-like Steve Cropper. Cropper, as part of the Stax rhythm section from Memphis, had written and played guitar on those timeless songs with Pickett and Redding, along with innumerable other, monster records.

When Covay would arrive at the studio, he would begin each session The author/engineer Glenn Berger in recent times. by grabbing me by the shoulders. He'd look me in the eyes, and say, "Glenn? Are we gonna make history today?”

The author/engineer Glenn Berger in recent times. by grabbing me by the shoulders. He'd look me in the eyes, and say, "Glenn? Are we gonna make history today?”

Feeling a surge of enthusiasm, I would say, "Yes!”

Then he'd say, "This time I'm not lyin'! Let's make a hit record!”

Since then, that's the way I try to start every day.