Almost half a century after its initial release, Yamaha’s classic three‑way monitor remains an impressive speaker, and it pioneered the use of diaphragm materials that are still considered cutting‑edge today.

Thanks to the application of new diaphragm materials, we’re fortunate to be around at a time of significant advances in the development of monitor drivers. Back in the March 2021 issue, for example, we reviewed the Ex Machina Soundworks Pulsar: the first monitor to incorporate graphene in a driver diaphragm. Graphene is so light and strong that only a couple of decades ago it would have been considered the stuff of science fiction. Along with Ex Machina Soundworks and graphene, there’s also quite a few monitor and OEM driver manufacturers working on diaphragms incorporating high‑tech composites, industrial diamonds and exotic metals. Focal’s beryllium tweeter domes are an example of the latter, but they weren’t first with the use of beryllium for a driver diaphragm. That honour falls to Yamaha, with the NS‑1000 series launched in the mid‑1970s. Yes, you read that right, Yamaha made a beryllium diaphragm tweeter over 25 years before Focal. But there’s more: the NS‑1000 series didn’t only boast a beryllium tweeter diaphragm; its 3.5‑inch dome midrange driver diaphragm was beryllium too.

Material World

The less common hi‑fi version of the NS‑1000 was slightly larger, and featured a hardwood cabinet rather than the NS‑1000M’s chipboard panels.

The less common hi‑fi version of the NS‑1000 was slightly larger, and featured a hardwood cabinet rather than the NS‑1000M’s chipboard panels.

The motivation behind the NS‑1000’s beryllium drivers was of course the material’s extraordinary combination of light weight and strength. In comparison with aluminium, also used very widely in driver diaphragms, beryllium is around two thirds as heavy but around three times as rigid. You can see why it might appeal to a speaker designer. The snags are that beryllium is rare, extremely difficult to work with, and, er, poisonous. Inhalation of its dust can result in life‑threatening health issues. Yamaha’s manufacturing process for the NS‑1000’s midrange and tweeter domes was vapour deposition of beryllium particles on a copper mould. When the required thickness of beryllium was achieved, the deposition process would be stopped and the copper mould removed. For the tweeter, the required thickness was 0.03mm (printer paper, in comparison, is typically about 0.1mm thick) and it resulted in a 30mm diaphragm that weighed around 0.03g. The midrange diaphragm was a little thicker and a little heavier, but not much.

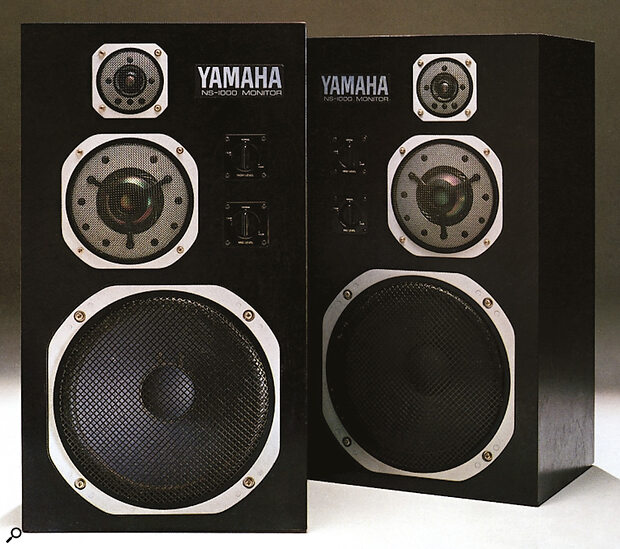

The NS‑1000 series comprised two three‑way passive speakers: the standard (and relatively rare) NS‑1000, aimed at the consumer hi‑fi sector; and the more ‘common’ NS‑1000M, aimed at studio monitoring applications. The two models differed in grille arrangements, cabinet finish and very slightly in size — the domestic version being a little larger. And where the domestic NS‑1000 featured a lacquered, solid hardwood construction, the NS‑1000M had a plywood‑braced chipboard cabinet finished with a ‘black ash’ veneer. While the NS‑1000M isn’t now a particularly common sight in studios (although my local studio, Brighton Electric, has a beaten‑up old pair doing background music duty in the bar!), there was a time when it was a popular monitoring choice in Japan and the US and among large broadcasters — the Finnish and Swedish national broadcast organisations, for example.

Yamaha originally described the NS‑1000s as ‘bookshelf’ speakers, however they must have had a somewhat ambitious view of what constitutes a bookshelf back then, because not only is the 67.5 x 37.5 x 32.6 cm cabinet way too big for any bookshelf of my experience, the 31kg weight would likely demolish all but the sturdiest of carpentry. The reality of NS‑1000s is that they’re most at home installed on serious speaker stands, and in any pro monitoring role they most comfortably fall into the midfield category rather than nearfield.

The reality of NS‑1000s is that they’re most at home installed on serious speaker stands, and in any pro monitoring role they most comfortably fall into the midfield category rather than nearfield.

Why The Weight?

The notable weight of the NS‑1000s arose for two reasons. Firstly, the cabinet construction is inspired by the ‘brick outhouse’ school of engineering. The panels are variously 25mm and 30mm thick and the internal bracing adds some significant additional heft. Internal corners are strengthened with hardwood fillets, and even the circular piece cut from the front panel for the bass driver aperture isn’t wasted; it’s attached to the inside back panel for some extra localised damping and rigidity. The result of the construction is a cabinet that feels as if it might have been hewn from solid wood. A knuckle wrap on the side results in a dull, non‑resonant thud (and potentially bruised knuckles).

A second reason for the weight is that the magnet systems fitted to the bass and midrange drivers are on the very large side. There’s also two reasons for this: more magnet power means that NS‑1000s offer usefully high sensitivity (90dB for 1 Watt into 8Ω) without a low input impedance that makes life difficult for amplifiers, and, specifically on the bass driver, it means that the NS‑1000 displays a very low‑Q bass resonance with minimal group delay and resonant overhang. The resulting shallow bass roll‑off also makes the speaker relatively tolerant of smaller spaces and locations close to walls. One of the first things that’s subjectively striking about the NS‑1000s is that bass stops, starts and reproduces pitch with surgical precision. It’s like an NS‑10 in that respect, but with an extra octave of low‑frequency bandwidth, incredible detail, way more neutral balance, and far higher maximum volume level capability.

Low frequencies on the NS‑1000 come courtesy of a 300mm (12‑inch) rigid paper cone driver, of conventional design but decidedly over‑engineered construction. It’s built for the long haul. I’ve mentioned the magnet already but the driver’s cast‑aluminium chassis is equally brawny. By today’s standards it looks a little agricultural, but there’s no doubting the chassis’s strength and fitness for purpose. The combination of the 50‑litre closed‑box cabinet and the bass driver results in a ‑3dB low‑frequency cut‑off at 50Hz, with a gradual 12dB/octave high‑pass filter slope.

Crossover from bass to midrange occurs at 500Hz with the tweeter then taking over at an unusually high 6kHz. This I suspect is one of the keys to the NS‑1000’s subjective character: the midrange driver, with its incredibly light and stiff diaphragm, and extremely low distortion, is responsible alone for the entire three and a half octaves where the richest seam of musical detail is typically to be found.

In being responsible only from 6kHz upwards, the tweeter has a relatively easy ride. Despite that, it’s possibly the weakest technical element of the NS‑1000 in that its frequency response is not particularly extended. It begins to droop from 10kHz, and by 15kHz it’s more significantly attenuated. As a result, it’s sometimes said that the NS‑1000s subjectively miss out a little on very high‑frequency detail. The reason for the tweeter’s limited bandwidth is unclear. High dome mass is unlikely to be responsible because it’s an established fact that the dome is beyond light, however there’s much more to tweeter frequency response than dome mass. Voice‑coil mass and electrical inductance also play a role.

It’s fair to say that a pair of NS‑1000s in good condition is likely to be pretty competitive with some of the best monitors around today.

The NS‑1000s were probably the first Japanese speakers to overcome the ‘not invented here’ prejudice that prevailed among European and US audio enthusiasts at the time. And they achieved that entirely through their unarguably brilliant performance. The surgical precision that describes NS‑1000 bass doesn’t stop there. It describes their entire performance. That, and explicit clarity and minimal tonal coloration at any volume level right up to very loud. I think it’s fair to say that a pair of NS‑1000s in good condition is likely to be pretty competitive with some of the best monitors around today. For a speaker design approaching 50 years old, that is remarkable.

What Came Next?

Yamaha discontinued the NS‑1000 series in the mid‑1980s, but continued to make the beryllium midrange and tweeter drivers until the mid‑1990s. Those drivers were fitted to a number of related speakers: the NS‑2000 and NS‑1000X, which introduced a carbon fibre bass driver diaphragm to the mix; and the NSX‑10000 that took the beryllium driver concept even further by extending use of the material to the midrange and tweeter voice‑coil formers. None of these models made anything like the impact of the original NS‑1000s however and, outside Japan, they are rare as hens’ molars.

Moving forward to near contemporary times, in 2016 Yamaha introduced the NS‑1000‑inspired NS‑5000. Along with a raft of fascinating technologies, that speaker debuted a new, high‑tech composite diaphragm material called Zylon (a thermoset liquid‑crystalline polyoxazole) for all three drivers. The NS‑5000 is around the same size as an NS‑1000 and weighs 35kg, but do they still call it a ‘bookshelf speaker’? Of course they do.

Buying Secondhand

So, if you’re intrigued by the idea of a pair of NS‑1000s, what are the pitfalls? Well the first one, obviously, is that any pair is likely to be between 35 and 45 years old (production stopped in the mid‑1980s) and will have suffered from the ravages of time. NS‑1000 drivers aren’t particularly known to be unreliable, however the only source of replacements that I’m aware of is from decommissioned speakers. You can’t call Yamaha and order a spare, you just have to scour eBay and hope. If you decide to take the plunge (a plunge that will probably cost at least £1200 in the UK), the first thing to do is take all the usual precautions when buying vintage audio gear: learn about the market, ask a lot of questions and walk away if there’s the slightest inconsistency in the answers or doubt about the veracity of the seller. Don’t just spend a distracted hour on eBay one evening and pull the trigger on the first pair that pops up. The second thing to do is take the NS‑1000s apart, clean and inspect everything, and carefully put them back together.

Being passive speakers, there’s no complex electronics to go wrong, however there are a few things to be aware of. Firstly, despite Yamaha’s high performance aspirations for the speakers, they were fitted with decidedly low‑rent spring connection terminals. What were Yamaha thinking? If I had a pair of NS‑1000s (and I’d genuinely love a pair), I’d consider replacing the spring terminals with a Speakon socket.

Secondly, The NS‑1000 crossover is a little idiosyncratic in that its higher‑value capacitors are created through parallel connected banks of lower‑value components. Back in the days before high‑value metalised polymer capacitors, a bank of reversible electrolytic capacitors was the only way of combining high, non‑polarised capacitance with low equivalent series resistance. There’s much talk on various speaker geek internet forums of replacing the capacitor banks with contemporary metalised polymer equivalents, however there’s also a school of thought that says the Yamaha capacitors were very high quality and don’t show significant degradation, so replacement is unnecessary. A more serious problem with the capacitor banks perhaps is that their solder joints to the circuit board are reported to suffer cracking with age, which might leave some or even all of them open circuit. Resoldering all the crossover components could well be worth the effort.

And thirdly, you’ll see from the photographs that Yamaha fitted a couple of variable resistance pots to provide some midrange and high‑frequency EQ options. Again, there’s two schools of thought out in NS‑1000 enthusiast land. One is that the pots should be removed and replaced with fixed‑value resistors once the preferred settings are established, and the second is that the pots should be left in place (not least because they’re quite useful), but regularly cleaned with isopropyl alcohol to ensure they don’t cause any connection problems. I think I’d be tempted by the latter option.