It might have lacked drawbars and tonewheels, but, sonically, the little–known Lowrey Heritage Deluxe was a match for any Hammond organ.

People often ask me “Why the Lowrey? Why not a Hammond?” Well, some people play a Gibson rather than a Fender. Some smoke Benson & Hedges, others Lambert & Butler. I suppose it’s a question of taste. But in this age of clones, modules and laptops, the Lowrey Heritage Deluxe, with its rat’s nest of circuits, proper switches, and super–visceral sound, is a refreshing if somewhat dusty breath of sonic fresh air. Tonally, it offers everything from classic soul jazz registrations to deep electronic fizzy buzzes, from nasal Stylophone–like reeds to end–of–the–pier theatre organ. And that’s just for starters. Plunder it some more and it starts to sound like a precursor to a polyphonic synth. So, owning and gigging one is not only about upholding a great British tradition of hard–swinging organ jazz and groovy rhythm & blues. It’s also about having a great bit of gear for the modern recording studio.

However, the Lowrey Heritage is a seriously endangered species, and the exact number still in existence in the UK is not known. So if you’re lucky enough to find one hidden behind suburban bay–window curtains, read on and learn of its secret majesty and why it has a significant place in electric organ history.

Off The Beaten Track

The author at his Lowrey Heritage Deluxe — with matching bench!Photo: Tommophoto.comMy first organ was a Hammond C3. I bought it in the mid–’80s when everyone else was buying a DX7. Like many Hammond owners, I listened to the greats: Jimmy Smith, Jack McDuff, Trudy Pitts and all that funky crowd. Then, one mid–1990s day at the height of the lounge scene, a DJ friend played me The Knack, a lilting string–laden ’60s film soundtrack by composer John Barry. This was my first encounter with the Lowrey Heritage and its curious sonorities. As the organ oscillations weaved in and around orchestral moods, I was struck by the satisfying deep electronic raspiness of its tone, and I couldn’t work out how it sounded so strangely dissonant.

The author at his Lowrey Heritage Deluxe — with matching bench!Photo: Tommophoto.comMy first organ was a Hammond C3. I bought it in the mid–’80s when everyone else was buying a DX7. Like many Hammond owners, I listened to the greats: Jimmy Smith, Jack McDuff, Trudy Pitts and all that funky crowd. Then, one mid–1990s day at the height of the lounge scene, a DJ friend played me The Knack, a lilting string–laden ’60s film soundtrack by composer John Barry. This was my first encounter with the Lowrey Heritage and its curious sonorities. As the organ oscillations weaved in and around orchestral moods, I was struck by the satisfying deep electronic raspiness of its tone, and I couldn’t work out how it sounded so strangely dissonant.

It was a bit of a surprise when I chanced upon a Lowrey Heritage advertised in Loot some years after first hearing its raw tones on record. I made arrangements to go and investigate. Upon first encounter I was immediately reassured by its off–white waterfall keys and solid–looking build (in other words, it was really heavy). I pressed chunky tabs, pulled things and generally prodded, but I didn’t really know what I was doing — I was too used to drawbars and Hammond registrations. And then I chanced upon that sound. The same sound I’d heard on the John Barry soundtrack.

The sound that hit me in that dimly lit Neasden living room seemed like a tight knot of tones and harmonics compressed, nay fracked, into a single note. What I was listening to was a harmonising trick brought about by what Lowrey deemed AOC, or, in long–hand, Automatic Orchestral Control. But this is an instrument from the early 1960s, right? So let’s not get too carried away with words like ‘automatic’ and ‘orchestral’ or indeed ‘control’. AOC is a kind of ‘wonderchording’ — a single note played on the upper manual, for example, fires whatever chord you’re playing with your left hand on the lower manual. So, if you’re playing a rather jazzy lower–manual D9b5 with your left hand, and playing the note F with your right hand on the upper manual, you obtain from that single note, well, something rather odd. But what a glorious odd it is.

Continue with a fast run on the upper whilst still holding said D9b5 and the sound is Lowrey! Press down all the keys on the lower manual (using your forearm if necessary) and then play a tune, and that strange dissonance, as heard on the John Barry soundtrack, will be all–apparent. Pair this with a requisite vintage Leslie tone cabinet or two and flatten the swell pedal, and it all goes up another level. Distinctive, incredibly full and fat, and most importantly, cool as hell.

What the Heritage lacks in drawbars, it makes up for in chunky rocker switches.The clever part is that, with AOC, the melody note always stays on top, so the chord constantly inverts underneath to accommodate the tune. By modern–day average home–organ auto–accompaniment standards, the Heritage’s AOC may seem pretty tame, but there’s a character there that set Lowrey apart from its contemporaries of the time. And even today when you hear it and use it, it has a raw sonic magic that other keyboards can’t match.

What the Heritage lacks in drawbars, it makes up for in chunky rocker switches.The clever part is that, with AOC, the melody note always stays on top, so the chord constantly inverts underneath to accommodate the tune. By modern–day average home–organ auto–accompaniment standards, the Heritage’s AOC may seem pretty tame, but there’s a character there that set Lowrey apart from its contemporaries of the time. And even today when you hear it and use it, it has a raw sonic magic that other keyboards can’t match.

Gliss & Glide

The Heritage also has other crazy stuff, like the switch located on the swell pedal which activates the Lowrey Glide. Engage it, and the pitch of the organ bends or ‘glides’ down a half tone, and then ‘glides’ back up when the switch is released. This was first introduced to Lowrey models in the late 1950s, and even by today’s standards, it sounds impressive and is distinct from your usual synth wheel–operated pitch–bend. I’m guessing there was never an attempt by Lowrey at this stage in development to make the drop more than an approximate semitone, and the slight variances between each oscillator mean the drop is uneven across a chord. But this adds a particular character to the sound.

Packed full of valve circuitry, the Heritage will certainly give you a warm feeling.There’s also the manual Sustain which, when introduced in the late 1950s, was already setting Lowrey apart from their competitors. Apply this to the Clarinet stop (tonally, a bright–sounding triangle waveform with a characteristic hollow sound), add Glide and vibrato, and you have the famous Lowrey Hawaiian Guitar. Aloha! Incredibly, it does indeed sound like a Hawaiian guitar as the Glide switch cancels the vibrato when it engages the drop in pitch, then the vibrato is subtly reapplied as the pitch returns.

Packed full of valve circuitry, the Heritage will certainly give you a warm feeling.There’s also the manual Sustain which, when introduced in the late 1950s, was already setting Lowrey apart from their competitors. Apply this to the Clarinet stop (tonally, a bright–sounding triangle waveform with a characteristic hollow sound), add Glide and vibrato, and you have the famous Lowrey Hawaiian Guitar. Aloha! Incredibly, it does indeed sound like a Hawaiian guitar as the Glide switch cancels the vibrato when it engages the drop in pitch, then the vibrato is subtly reapplied as the pitch returns.

When Sustain is applied to more sawtoothy tabs like the String or Oboe, the organist is able to produce an expansive polyphonic, glassy sound that wouldn’t go amiss in a Vangelis composition. Put it through a hot Leslie set to fast, add AOC and the sound is huge and all–enveloping, like a Wurlitzer cinema organ. These larger–than–life sounds were important features when selling organs to the general public in the early 1960s.

Diamond Head

One example of the Heritage sound many readers will know is the opening to the Beatles’ ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’. Paul McCartney uses the 8’ preset ‘percussion’ voices: a mixture of Vibraharp, Guitar and Music Box (so legend has it). It has a shimmering, metallic quality which is yet to be heard replicated on any synth. A Fab Four virtual instrument plug–in manufactured by East West was released a few years ago and featured this sound sourced, apparently, from an original Lowrey.

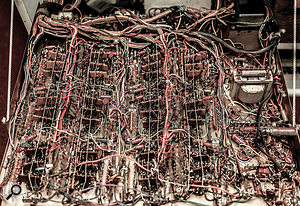

No tonewheels... but a lot of wires!Garth Hudson of the Band used a Lowrey Festival FL, the big console brother of the Heritage, which had a few extra features as well as coming in a bigger mahogany box with two five–octave manuals as opposed to the Heritage’s overlapping 44–note affairs. Ostensibly the Festival was Lowrey’s answer to the Hammond B3. They even gave it the four–poster look. Rare as hens’ teeth these days. If you see one, and you have the space, grab it.

No tonewheels... but a lot of wires!Garth Hudson of the Band used a Lowrey Festival FL, the big console brother of the Heritage, which had a few extra features as well as coming in a bigger mahogany box with two five–octave manuals as opposed to the Heritage’s overlapping 44–note affairs. Ostensibly the Festival was Lowrey’s answer to the Hammond B3. They even gave it the four–poster look. Rare as hens’ teeth these days. If you see one, and you have the space, grab it.

After the Doors’ first album, Ray Manzerek switched from a Vox Continental to a Gibson G101. This famous combo organ was manufactured and designed by Lowrey, but with a Gibson badge stuck on it. The sound could be described as a transistorised Heritage in a combo shell, although the G101 had the combo organ paraphernalia of the time, like the reverse keys for left–hand fuzzy bass sounds, and it emphasised the more fizzy aspects of Lowrey’s tonal spectrum. The famous Lowrey Glide with Sustain can be heard on the Doors composition ‘The Unknown Soldier’.

The two big names of the instrument are Brit jazz organ supremoes Alan Haven and Harry Stoneham. Alan Haven did for Lowrey what Jimmy Smith did for Hammond in terms of musical prowess and gaining exposure for the manufacturer. Haven had that rare character organists dream about: an unmistakable style and sound. He was one of the few UK organ artistes to have success in the US, and was John Barry’s organist par excellence. When I spoke to him a few years ago and asked him why he played the Heritage and not a Hammond, he answered, with a shrug of the shoulders, “I just liked it.” Listen to his 1960s live duo performances with his drummer, the great Tony Crombie, and you’ll be listening to the kind of jazz organ playing that doesn’t exist any more. He was a ferociously good bass–pedal player, too, often dedicating a section of his live show to his incredible, jazzed–out footwork. Harry Stoneham, who became a household name as Musical Director on the BBC’s Parkinson show, championed the Heritage on his early recordings and later switched to Lowrey’s transistorised models. His version of ‘Comin’ Home Baby’ is a DJ favourite.

The two big names of the instrument are Brit jazz organ supremoes Alan Haven and Harry Stoneham. Alan Haven did for Lowrey what Jimmy Smith did for Hammond in terms of musical prowess and gaining exposure for the manufacturer. Haven had that rare character organists dream about: an unmistakable style and sound. He was one of the few UK organ artistes to have success in the US, and was John Barry’s organist par excellence. When I spoke to him a few years ago and asked him why he played the Heritage and not a Hammond, he answered, with a shrug of the shoulders, “I just liked it.” Listen to his 1960s live duo performances with his drummer, the great Tony Crombie, and you’ll be listening to the kind of jazz organ playing that doesn’t exist any more. He was a ferociously good bass–pedal player, too, often dedicating a section of his live show to his incredible, jazzed–out footwork. Harry Stoneham, who became a household name as Musical Director on the BBC’s Parkinson show, championed the Heritage on his early recordings and later switched to Lowrey’s transistorised models. His version of ‘Comin’ Home Baby’ is a DJ favourite.

Old Soul

Don’t be tempted to go out and buy any old Lowrey from eBay after reading this. In particular, be aware that Lowrey used the same model names for later digital organs aimed solely at the home–organ market. Lowrey made their gutsiest, grittiest models in the early 1960s, those being the Heritage DSO, Lincolnwood SSO25, Brentwood MSO, Festival FL/FLO, Coronation CNO and the Church CLO. By 1965 the Heritage was transistorised into models such as the Holiday TLO–R, Berkshire TBO–1 and the console Lincolnwood TLO–25, all of which are pretty good organs with some tasty features (the Holiday was a Soft Machine favourite), but these trannies don’t quite have the soul of the original Heritage–era models. And by 1970 Lowrey were already heading straight for the nascent home organ market, at which point we may as well say adieu. It was fun while it lasted.

Part of the instrument’s unique appeal lies in its classic retro styling.It’s unlikely that the giants of keyboard manufacturing like Nord or Roland would consider investing in research to redevelop or clone the Lowrey Heritage Deluxe the same way they have gone about resuscitating the Hammond tonewheel organ. But that’s a good thing, because the handful of Heritage owners that remain know they have something special, something off the radar — and they’re probably doing a good job of keeping them working. And it’s reassuring to think we won’t be confronted by those dreary blindfold tests where we have to guess which is the clone and which is the real thing.

Part of the instrument’s unique appeal lies in its classic retro styling.It’s unlikely that the giants of keyboard manufacturing like Nord or Roland would consider investing in research to redevelop or clone the Lowrey Heritage Deluxe the same way they have gone about resuscitating the Hammond tonewheel organ. But that’s a good thing, because the handful of Heritage owners that remain know they have something special, something off the radar — and they’re probably doing a good job of keeping them working. And it’s reassuring to think we won’t be confronted by those dreary blindfold tests where we have to guess which is the clone and which is the real thing.

If you do find one expect to pay anything between not much and £1000 or so, depending on condition and, crucially, whether or not it comes with the original matching bench! And be warned that ‘spares or repair’ will mean just that — lots of time (and tech fees if your troubleshooting skills are limited) replacing and rewiring as the values of certain components will have drifted considerably. Alternatively, you’ll be left with plenty of spares you can sell to people like me. Long may those dusty circuits live!

Rory More is the resident organist at the Bethnal Green Working Men’s Club, London E2. His latest LP Looking For Lazlo is available on Sudden Hunger Records.

Reinventing The Tonewheel

Unlike the Hammond B3, which is electromechanical and uses magnetic pickups applied to tonewheels to create sine waves, the Lowrey Heritage is 100 percent electronic. I’m talking wires. Lots of wires. Heritage owner and vintage organ enthusiast Jerry Hall explains: “The Hammond organ uses an ‘additive synthesis’ approach where the organist builds up a sound by using a set of nine drawbars, each one acting as a volume control for a particular harmonic. In contrast, the Lowrey Heritage starts out with a complex tone signal and then applies one or more filters to reduce or eliminate certain harmonics. Today, we call this ‘subtractive synthesis’ — a technique used in many conventional synthesizers.

“Unlike the original Hammond organs, with their electromechanical tone generators, the Lowrey Heritage is an entirely electronic organ, and uses 1950s–style valve radio technology to produce its sounds. Twelve tone generators are provided, one for each musical note. Each generator comprises a master oscillator, tuned to the highest fundamental frequency needed for that note, followed by a series of three or four frequency–divider circuits. The dividers halve their input frequency to produce an output exactly one octave lower. The tones produced by the dividers have a different harmonic content compared to the oscillators, and so the generator circuits apply some mixing to make them more useful for obtaining the various organ voices. Ultimately, the generated tones are passed through to the ‘Quality Control’ section of the instrument when keys are played. Here, they are modified by various filter circuits according to the stop tabs selected by the organist. Additional circuitry tricks are employed to derive even more tones beyond the range of the main tone generators. Some of these tricks were clearly compromises intended to simplify manufacturing and reduce costs, but they also make a significant contribution towards the instrument’s unique sound.”

So, electronically speaking, the Heritage has got a lot going on: more so in many ways than its cousin, the tonewheel Hammond. With so much circuitry inside its thick mahogany shell, more than 50 valves protruding from its generator panel and other complex components, such as a constellation of neon lamps and endless frequency–doubling circuits, the Heritage is prone to malfunction. Many died a lonely death, ending up in the local skip because of recurring technical faults, constant repair bills and replacement by more reliable transistorised models.