Lynx have drawn on their existing Hilo2 and Aurora(n) designs to create a powerful desktop audio interface.

It’s one of the more niche league tables in the world, but Hugh Robjohns’ chart of measured dynamic range performance on the SOS Forum tells you a lot about the current state of audio interface design. In general, newer interfaces score more highly than older ones, though a few classics such as the UA 2192 and Lavry AD11 still compete. And, as you’d expect, the upper reaches are dominated by relatively costly products.

The Lynx Hilo2, released late last year, is the only current interface that features in the top five for both A‑D and D‑A measurements. Such performance naturally comes at a price, and depending on which variant you opt for, you can expect to pay upwards of £4k for a two‑input device that operates only at line level. Mastering engineers and serious classical music purists will love it, but many small studio owners will find it unaffordable and its I/O too limited.

The idea that Lynx could address both concerns in a single product sounds counterintuitive. Surely there would be no way to simultaneously increase the Hilo2’s input count, add mic preamps and monitor control, and reduce cost, without resorting to drastic measures like offshoring their manufacturing, or drastically reducing sound quality? Well, apparently there was a way — and the result is the Lynx Mesa.

Going Hi

How have they achieved this? For one thing, whereas the Hilo2 can be configured as a Thunderbolt, USB or Dante device using optional cards, those options have been closed off on the Mesa, which is available only in a fixed Thunderbolt 3 variant. Lynx have also saved a few pennies (like other manufacturers) by not including any way to actually connect it to your computer, so you’ll need to add a certified Thunderbolt 3, 4 or 5 cable with Type‑C connectors to your shopping basket. Additionally, the Mesa lacks the Hilo2’s internal PSU and battery power option, drawing its current instead from an external ‘line‑lump’ PSU.

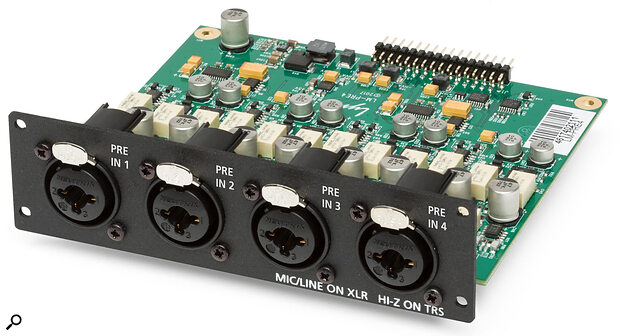

On the analogue side, the Hilo2 is a two‑in, four‑out device, whereas the Mesa is the other way around, losing the XLR line outputs but gaining a second pair of inputs. What’s more, all four of its analogue inputs are on combi XLR/jack sockets and feature the same comprehensive digitally controlled mic preamps that are available for the same company’s Aurora(n). The Mesa has two built‑in headphone amps to the Hilo2’s one; these have independent volume controls but always present the same signal. Another Mesa feature derived from the Aurora(n) and not found on the Hilo2 is built‑in multitrack recording to an SD card.

In terms of digital I/O, the Mesa retains the Hilo2’s single optical input and output, which can operate either as ADAT Lightpipe or stereo S/PDIF, as well as the word‑clock I/O on BNC connectors and the dedicated coaxial S/PDIF I/O. However, it lacks the Hilo2’s dedicated AES3 in and out on XLRs. A single Type‑C socket takes care of connection to the host computer.

The Mesa features four analogue inputs, all with preamps and all capable of accepting DI guitar signals.

The Mesa features four analogue inputs, all with preamps and all capable of accepting DI guitar signals.

Touch Typing

Although there’s a lot in common under the hood with other Lynx products, the Mesa represents a clean break in terms of industrial design. Its stylish, asymmetrical case is made from chunky metal, and seems designed to act as a heat sink; at any rate, it gets pretty warm in use. The gently sloping top panel makes the ideal home for the full colour touchscreen, which is impressively clear from all viewing angles, bright enough to use in direct sunlight, and precise and responsive to touch. It’s joined there by four buttons, a large rotary encoder and potentiometer volume controls for the two headphone sockets. These are found to the right of the curved front panel, with a slot for an SD card to the left. All other I/O is tucked away on the rear panel.

The obvious comparisons are with the Neumann MT48 and its close sibling, the Merging Anubis. The Mesa does indeed bear some similarities to these devices, both in terms of physical design and functionality, and perhaps the most striking of them relates to the use of the touchscreen. I’ve reviewed other touchscreen‑equipped interfaces where the screen felt at best a luxury and at worst a form of window dressing. That’s not the case with either the Mesa or the MT48/Anubis, which exploit their screens to the fullest. In both cases, in fact, the screen offers pretty much all the functionality that’s available from the control panel application running on the attached computer. So, not only can you configure the Mesa and perform basic housekeeping, but you also get full control over its internal mixer. There’s even a built‑in Help system, which is a nice touch.

There are also some important contrasts between the Mesa and the Neumann/Merging products. I’ll get to the functional differences later, but from a control point of view, the main one is that the MT48 and Anubis serve the control panel and mixer as web pages. This means they can be accessed from any device that can run a browser and connect to the same Wi‑Fi network as the host computer, so you can for example make adjustments from the live room, or allow musicians to set up their own cue mixes. By contrast, the Mesa currently offers no remote control options, but on the plus side, its graphical interface is rather more attractive to look at than those of the MT48 and Anubis.

Megamix

At base sample rates, the Lynx Mesa presents a total of 16 inputs and outputs to your DAW. On the input side, these comprise four mic/line/instrument inputs, coaxial S/PDIF, a stereo loopback input, and up to eight optical digital inputs. On the output side, your DAW simply sees eight pairs of outputs labelled Play 1‑2, Play 3‑4 and so on. Each physical output pair in effect has its own mixer, with its own independent balance drawn from both the inputs and the DAW playback channels. Playback from any of the 16 SD card channels can also be freely mixed in on a per‑output basis. It’s an extremely flexible mixing and routing system, with virtually no limitations as to what can be sent where. Even the outputs have their own dedicated faders.

Having said that, there are no signal‑conditioning facilities at all apart from polarity switches and high‑pass filters on the four analogue inputs. If you like your low‑latency cue mixes to feature EQ and dynamics, or effects such as reverb and delay, that’s not possible here. Curiously, there’s also no solo or PFL bus, which seems a strange omission in an otherwise comprehensive mixing arrangement.

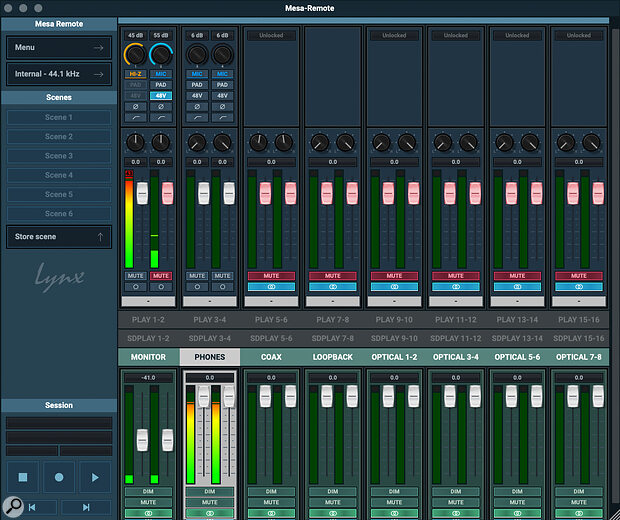

On a Mac or PC, control over the mixer is handled using a utility called Mesa‑Remote. As previously mentioned, this pretty much duplicates the functionality that’s available from the touchscreen. It also uses similar graphics and colour schemes, though Lynx have chosen to lay things out differently to take advantage of the larger display area available on a typical computer. One of the few functions exclusive to Mesa‑Remote is the ability to save and load mixer Scenes. These can be assigned to six on‑screen buttons, for instant recall.

Mesa‑Remote runs on your Mac or PC as an alternative to the touchscreen. In this screenshot, the fader banks for the DAW and SD card playback channels are collapsed.

Mesa‑Remote runs on your Mac or PC as an alternative to the touchscreen. In this screenshot, the fader banks for the DAW and SD card playback channels are collapsed.

Inputs, playback channels, SD playback channels and outputs each have their own bank of faders, which appear in four rows. The output faders are always visible, and indeed it’s necessary to select an output pair in order to see what mix is being adjusted. The other three rows can be collapsed, but I do feel the Mesa‑Remote user interface could use a little refinement. With more than two fader banks expanded, the entire interface won’t fit on a laptop screen, and if the output channels are out of view, there’s no colour coding or other information to tell you which one is currently selected. And if you want to scroll with a trackpad or wheel, you’ll need to be careful where the mouse pointer is positioned; if you leave it over a fader or pan control, your gesture will move the fader rather than scrolling the window.

Talk & Listen

Although there’s no ‘master channel’ as such in the Mesa’s mixer, it does have some monitor control and master section features. The main rotary encoder can govern the output fader level either for the main monitors or the headphones, and it has a secondary press action that can be dim or mute. There’s also a dedicated mute button, which can be assigned either to Current Output or to any combination of physical outputs. And although there’s no built‑in talkback mic, it’s possible to repurpose one of the Mesa’s analogue inputs for this function. Speaker switching is obviously not an option, since there is only one pair of line‑level outputs. Sadly, there’s no way to generate a mono fold‑down of the monitor signal within the Mesa mixer.

The two top‑panel buttons to the left of the group of four are assignable. A nice touch is that they can have different functions depending on whether an SD card is inserted or not. The physical buttons display the universal circular record and triangular play icons, reflecting their default functions when a card is inserted, but they can also be used as shortcuts to reach different mixer pages, or as either latching or momentary talkback buttons. The third button toggles between displaying the Mesa’s metering view, which can represent signal levels at all of its inputs and outputs, and the main menu.

Hot Mesa

As I mentioned at the start of this article, the Lynx Hilo2 is one of the best all‑round performers on the market in terms of A‑D and D‑A quality. Some of the Hilo2’s more esoteric or audiophile options are omitted on the Mesa, notably the choice of converter filtering modes, and it doesn’t quite achieve the same numbers, but it’s very impressive nonetheless. Output dynamic range is 120dBA both on the monitor outputs and the headphone outputs. The latter are punchier than those found on most audio interfaces, delivering a maximum output level of +18.4dBu and up to 383mW into a 60Ω load. In line input mode, its analogue ins achieve an A‑weighted dynamic range figure of 119dB, and are flat to within ±0.01dB from 20Hz to 20kHz.

Switch the inputs to mic mode, and the dynamic range falls a little, but only to 116dB. More importantly, Equivalent Input Noise is an impressively low ‑129dBu (A‑weighted). Gain is variable in 1dB steps over a 63dB range, with a switchable pad extending this at the lower end by 13.6dB. The hottest level that can be accommodated is a beefy +28.7dBu, whereas in line mode, the Mesa is aligned such that 0dBFS corresponds to +20dBu. The jack part of the combi input is used only for high‑impedance sources, and presents a 1MΩ impedance when used unbalanced or 2MΩ balanced.

The Mesa’s mic preamps are the same design used in the LM‑PRE4 module for Lynx’s Aurora(n).

The Mesa’s mic preamps are the same design used in the LM‑PRE4 module for Lynx’s Aurora(n).

In terms of its technical performance, in fact, the Mesa mirrors Lynx’s Aurora(n) rather than the Hilo2. You could think of it as a product that combines that interface’s audio circuitry with the Hilo2’s touchscreen‑based control paradigm. And subjectively, it sounds very good indeed. I would have no qualms whatsoever about using it on any recording, and I’d be perfectly happy to employ its built‑in preamps on absolutely anything. What’s more, although it’s arguably better featured than the Hilo2, the Mesa is little more than half the price of that flagship converter.

However, half of the price of a Hilo2 is still a lot of money. For the price of the Mesa, you could have your pick of 1U rackmounting interfaces from the likes of RME, Universal Audio, MOTU or Metric Halo. Most of these would offer broadly comparable tech specs and more comprehensive I/O, albeit without the Mesa’s rather lovely touchscreen. In the desktop arena, the Mesa faces more affordable competition from the Antelope Audio Zen Tour Synergy Core, which has extra I/O and features an onboard plug‑in‑style effects platform; it even has a touchscreen, though its potential is not fully exploited. But, as I’ve already mentioned, the most obvious rivals for the Mesa’s crown are the Merging Anubis and the closely related Neumann MT48.

No Wrong Answers

You’d have to be an exceptionally picky engineer with golden ears to base your choice on perceived sound quality. The Mesa is faultless in this regard, but the Anubis platform actually betters it on paper, with exceptional specs and subjective performance. The touchscreen implementations are about equally excellent, and leave products such as the aforementioned Zen Tour and the Apogee Symphony well behind. In terms of built‑in local I/O, the Anubis and MT48 are perhaps more like the Hilo2 than the Mesa, with multiple outputs but only a single pair of inputs, though these do have preamps. They also have two fully independent headphone outs, but the Anubis lacks the optical I/O found on the MT48 and Mesa.

In short, it’s a tough choice, and to my mind it comes down to three factors: expandability, ease of use, and connection protocol.

To take the last of these first, the Anubis connects to a computer over Ethernet, originally using the RAVENNA protocol but now with the option of Dante as an alternative, whilst the MT48 offers the choice of Ethernet or USB. On my Mac, Ethernet operation with the RAVENNA firmware delivered a round‑trip latency of around 3.6ms at 44.1kHz with a 16‑sample buffer size. With the MT48 on USB, the smallest buffer size on offer is 32 samples, which results in around 5ms total latency. Being a Thunderbolt interface, I expected the Mesa to beat this, but in fact it’s marginally less good, with the smallest 32‑sample buffer size producing a round‑trip latency of 6ms at 44.1kHz. All of these are very respectable figures, but they don’t give the Mesa a point of difference.

Meanwhile, the Anubis and MT48 score heavily on expandability. Yes, they lack the Mesa’s dedicated S/PDIF I/O and its word‑clock sockets, but both can operate as part of an audio‑over‑IP network, opening up more or less endless possibilities. Better still, Merging’s ‘peering’ technology allows the Anubis and MT48 to control other Merging interfaces in a seamless fashion, whereby the additional I/O is simply incorporated into the Anubis mixer. Said mixer is also even more powerful than that of the Mesa, with built‑in EQ, dynamics and reverb available on top of an equally flexible routing and mixing architecture. In the case of the Anubis, it’s even possible to carry out monitor calibration internally.

The Mesa abounds with thoughtful design touches, such as the ability of the inputs to auto‑sense what sort of source is connected and adopt the correct mode without user intervention.

The flip side of this is that ease of use certainly favours the Mesa. Configuring a RAVENNA network isn’t too bad as IT admin goes, and Merging’s UNITE setup utility takes quite a lot of the pain away, but I don’t think the Anubis will ever be ‘plug and play’ in the way that the Lynx unit is. And although Merging’s touchscreen implementation is equally powerful and permits remote control, Lynx’s is more polished and graphically sophisticated. The Mesa also abounds with thoughtful design touches, such as the ability of the inputs to auto‑sense what sort of source is connected and adopt the correct mode without user intervention.

Finally, the value of the Mesa’s built‑in audio recording shouldn’t be underestimated. I can only think of a handful of other interfaces that support direct recording either to SD cards or USB devices. You wouldn’t choose to leave the laptop at home and track a crucial session this way, but the benefits of having a (somewhat) redundant recording platform churning away in the background are obvious. Whether it’s acting as a backup in case of computer failure, or simply documenting the session so that you can recall ideas and jams that didn’t get tracked to the primary system, it offers peace of mind that isn’t easily obtained in other ways.

SD Card Recording

Like Lynx’s modular Aurora(n) system, the Mesa has the ability to use a Micro SD card for 16‑track recording and playback. This process is not covered in depth in the PDF manual, but it’s clear that a lot of thought has gone into making it as intuitive as possible. Insert a card into the front‑panel slot, and (unless you’ve modified the settings) the F1 and F2 buttons light up red and green respectively, indicating that they have now become Record and Play controls. A fuller selection of transport controls appears on the touchscreen and in the Mesa‑Remote software. What’s more, the Mesa automatically senses which inputs have signal coming in, and record‑arms only those tracks — though, again, this can be overridden if you need to.

...the value of the Mesa’s built‑in audio recording shouldn’t be underestimated.

Recordings are organised into Sessions, each of which can comprise multiple Takes, which are recorded as single poly‑Wave files. There is no way to drop into or overdub onto an existing take, or reorder the channels, so a guitar that was recorded through input 4 will always be played back on SD Play channel 4, regardless of whether tracks 1‑3 are used. As far as I can tell, there’s also no way to manually locate the playback head or cursor within a take, so playback always starts from the beginning. Takes can also be organised into Playlists in the standard XSPF format. Takes within a Playlist are automatically played back one after the other. Oddly, takes and sessions can be managed, selected and named from the touchscreen, but not from Mesa‑Remote. Nor is there a straightforward way to transfer audio files from the SD card to the computer; you’ll need to remove the card and insert it into your Mac or PC’s card reader.

Pros

- Slick design with superb touchscreen implementation.

- Good audio specs and subjective sound quality.

- Easy to set up and use.

- Built‑in SD card recording.

- Highly flexible internal routing and mixing.

Cons

- Limited monitor control.

- Internal mixer has no EQ, dynamics or solo/PFL bus.

- Both headphone sockets carry the same signal.

- No Thunderbolt cable included.

Summary

The Mesa is a stylish, powerful and good‑sounding desktop Thunderbolt interface, with an excellent touchscreen implementation and the useful ability to record directly to SD cards.

Information

When you purchase via links on our site, SOS may earn an affiliate commission. More info...