Hip‑hop and metal share more in common than you might think, as mixer Ari Morris confirmed when he worked on Moneybagg Yo’s hit album, A Gangsta’s Pain.

“I’m not a technical mixer. For me it’s all about feel and vibe. It’s all heart for me. There’s very little science involved in any of my process. This means that I have a hard time explaining what I’m doing, because I just kind of close my eyes, and go. It’s why I work a lot with rap music, because the beauty of rap music, and what drew me into it, is that it is all about vibe.

“Rap is not about things needing to be technically right. A 12 year old can make a beat at a high level, because it’s all about a feeling. And for me, the sledgehammer feel of an 808 is the same as the sledgehammer feel of a big, chunky, heavy metal guitar. At the same time, you have to make each rapper sound distinct and uniquely them, to their core, so that if you’re a fan, you’ll instantly recognise them and are going to love their music.”

Ari Morris.Ari Morris may claim to have a hard time explaining what he does, but in just a few sentences he neatly summed up some of the principles at the heart of his process. Morris has put his vibe skills to good use with a range of rap artists, like Young Dolph, Future, Rod Wave, Royce da 5’9”, EST Gee, 42 Dugg and, most of all, Moneybagg Yo. His vocal engineering and mixing credits on Royce da 5’9”’s album The Allegory (2020) earned Morris his first Grammy Award nomination (for Rap Album Of The Year), and his ongoing mix work for Moneybagg Yo resulted in a US number‑one album, A Gangsta’s Pain (2020). The album spawned several big singles, including the platinum ‘Time Today’, and ‘Wockesha’, which reached number one on the Main R&B and Hip‑Hop chart and the US Urban Radio chart.

Ari Morris.Ari Morris may claim to have a hard time explaining what he does, but in just a few sentences he neatly summed up some of the principles at the heart of his process. Morris has put his vibe skills to good use with a range of rap artists, like Young Dolph, Future, Rod Wave, Royce da 5’9”, EST Gee, 42 Dugg and, most of all, Moneybagg Yo. His vocal engineering and mixing credits on Royce da 5’9”’s album The Allegory (2020) earned Morris his first Grammy Award nomination (for Rap Album Of The Year), and his ongoing mix work for Moneybagg Yo resulted in a US number‑one album, A Gangsta’s Pain (2020). The album spawned several big singles, including the platinum ‘Time Today’, and ‘Wockesha’, which reached number one on the Main R&B and Hip‑Hop chart and the US Urban Radio chart.

According to Morris, DeMario DeWayne White Jr, aka Moneybagg Yo, comes to him exactly because of their resonance over vibe, and the mixer’s capacity to make the rapper sound unique. “He knows that I’m going to care about every second of his music just as much as he does. From there it’s about the subtleties of how he likes his voice to be heard, and how he likes to hear music in general. He calls me because I understand the vision in his head, without the need to reference other things. One of the most beautiful things about working with an artist like Bagg, with such a strong sense of self, is that we never reference anyone else’s music.”

From Hardcore To Hip‑hop

At this point it’s necessary to take a few steps back, and examine where Morris himself is coming from, both literally and figuratively, and explain how he arrived at his vibe‑over‑technology approach, his relationship with Moneybagg, hearing 808s like heavy metal guitars, and ended up in Memphis. Morris takes up the story.

“I’m originally from New Jersey, and I started played guitar when I was 10 or 11. Most of my teenage years were spent playing in bands, and it’s how I discovered recording. I started on the blue Tascam DP01 8‑track, which was all digital. My first foray into making money from music was recording people’s audition tapes for music schools with that machine! The hardcore punk movement was big in New Jersey, so I grew up as a metal head. I also was heavily into East Coast hip‑hop.

“I came down to Memphis on a whim. I went to study at the Rudy E Scheidt School of Music at the University of Memphis, and found the huge musical heritage in this city, going back historically to Stax Records, Sun Studios and Royal Studios, and moving forwards into hip‑hop and trap. I had been aware of the history, but not of everything that’s happening today. There’s a real music vibe here. Many people have innate, crazy artistic talents!

“While studying, I started working as an intern in studios in Memphis, and worked my way up. During that time I linked with a couple of artists who were coming up at that time in Memphis, like Young Dolph. I worked with him and his label Paper Route Empire for years. From there I linked up with Moneybagg, early in his career in 2016, and did a bunch of early projects with him that led to him signing with a major label.”

Ari Morris: I’ve always loved metal and rap, but when I came down here and really started experiencing the trap community, it felt very similar to the punk and hardcore community. It’s the same ethos, the same attitude...

Mentors

Morris mentions engineer/mixer Malcolm Springer and in particular Nil Jones as his mentors. “Nil is very into soul, funk and hip‑hop, and known for the implementation of a live band within trap music. I sat behind him mixing for years, and I learned everything from him! I learned from him how to be in the studio, which is the first thing, and how to translate an artist’s vision into their record, rather than your own. It always has to be about the artist and what they’re looking for. I also worked in studios in Atlanta and LA, until about five years ago, when I settled into mixing in my own comfy studio place in Memphis.”

So, how did a self‑declared ‘metal head’ end up working predominantly in rap in general and trap in particular? “I’ve always loved metal and rap, but when I came down here and really started experiencing the trap community, it felt very similar to the punk and hardcore community. It’s the same ethos, the same attitude: ‘Fuck you, I’m going to do what I want to do.’ It’s that mentality. It is so raw. It also is a raw recording style. With the early trap records that I mixed, in my head it was heavy metal with 808s. It was like, how do I channel this raw aggression into this record?”

So, how did a self‑declared ‘metal head’ end up working predominantly in rap in general and trap in particular? “I’ve always loved metal and rap, but when I came down here and really started experiencing the trap community, it felt very similar to the punk and hardcore community. It’s the same ethos, the same attitude: ‘Fuck you, I’m going to do what I want to do.’ It’s that mentality. It is so raw. It also is a raw recording style. With the early trap records that I mixed, in my head it was heavy metal with 808s. It was like, how do I channel this raw aggression into this record?”

It was their mutual love of channelling raw aggression in recording that drew Moneybagg and Morris together in 2016, and that led the rapper and his label in 2019 to call Morris back in, after the rapper’s first two albums on Interscope were mixed by others. “I did engineering and mix work on some of his early mixtapes like ELO and All Gas No Brakes, and the 2 Federal mixtape with Yo Gotti that led to the label deal (all 2016). There was a vibe and an energy in the vocals on those, and when they came back to me they said they were after that vibe.

“So when I started working with Bagg again in 2019, I went for this vibe, which sits in the tonality of his vocal and in the placement. I put him in a different spot than where many other people would place a vocalist. It’s unique and distinct. It’s about creating something that’s in your face and bone‑dry. Bagg hates the traditional ear candy like delay throws, reverb swells, reversing things and panning them around, and so on. It’s not how he feels music. It takes you out of the moment. Instead the feel with him is bone‑dry, raw power, maintain the size and the weight and the heft of a real record, and create this big thing that’s not covered in fluttery ear candy.”

Transformers

Another essential ingredient in the unique sound Morris gets is, he says, “transformers, transformers, transformers”. Which brings us to his studio in Memphis, where Morris has mixed everything Moneybagg Yo has released over the least two years, including the albums Time Served (2020) and A Gangsta’s Pain. For four and a half years Morris worked in a tiny 8 x 10‑foot control room, but he recently moved to a much larger space, which is set in a 3000 square‑foot warehouse.

Morris mixing at his “comfy new studio” in Memphis, with his two woofers.

Morris mixing at his “comfy new studio” in Memphis, with his two woofers.

“A Gangsta’s Pain was the last big project that I mixed in my previous place. But both my studios have the same gear. All I added when I came to my new place was a McDSP APB. I love that box. My monitors are Amphion One18s and Two18s, and Genelec 1032As, which are 28 years old, paired with a BassBoss DJ18s subwoofer. I used to be an NS10 guy religiously, until I heard the One18, and I was like ‘Oh, shit,’ swapped my NS10s for those, and never looked back. My I/O for Pro Tools is an Apollo 8, which feeds my Neve 5060, and Burl B2 Bomber A‑D/D‑A for printing back into Pro Tools.

Central to Morris’ mixing workflow is a Rupert Neve Designs 5060 mixer.“I have a hybrid setup, and the Neve 5060 desktop mixer is the heart of my studio. It also functions as my monitor controller. It has four input faders and a mix fader, and no EQ or compressors, just in and out transformers on every channel. I was trying to find a monitor control that sounds like a console, because I came up working in rooms with a Neve or an SSL desk. The main desk I worked on was a Neve VR60, and it is my favourite board to this day. The 5060 gives me a similar sound. It’s just channels of irons. Lots of transformers.

Central to Morris’ mixing workflow is a Rupert Neve Designs 5060 mixer.“I have a hybrid setup, and the Neve 5060 desktop mixer is the heart of my studio. It also functions as my monitor controller. It has four input faders and a mix fader, and no EQ or compressors, just in and out transformers on every channel. I was trying to find a monitor control that sounds like a console, because I came up working in rooms with a Neve or an SSL desk. The main desk I worked on was a Neve VR60, and it is my favourite board to this day. The 5060 gives me a similar sound. It’s just channels of irons. Lots of transformers.

“In addition to the 5060, I have a couple of key compressors, the UA Rev D 1176 and a Rev A 1176, for if I really want to pump the vocals. I also have Vintech X73i and Avalon VT737 mic pres, and the output of my 5060 goes to my AudioScape G bus Compressor, and then into the Burl B2 Bomber, which is another set of transformers. Lots of transformers and stages in analogue that can clip and be hit hard are my answer to getting low mids in my records.”

The latter remark is a reference to a problem that many mix engineers today face: with the focus on heavy low end and sub bass, and extreme brightness, the midrange is often forgotten. This despite the fact that, as Morris acknowledges, “Your money is in the midrange. Getting the midrange in there and making sure it feels like a record is part of the art of being a mix engineer. For me the answer is lots of saturation from plug‑ins, for example using iZotope’s Ozone, Soundtheory’s Gulfoss, the SPL IRON compressor, and then all the transformers in my studio.”

Stems Or A Two‑track?

Morris was asked to illustrate his mix approach with his mix of Moneybagg Yo’s track ‘Wockesha’, the most recent hit from A Gangsta’s Pain. The mix engineer’s reaction was illustrative of his general vibe‑over‑tech attitude. Over the last few years it’s become a common complaint among mix engineers working in the trap genre that they are sometimes just required to mix a handful of vocal tracks in with a two‑track (stereo print) of the beat. To say that top mix engineers are over‑qualified for these mixes is an understatement.

Morris’ outboard rack, featuring (from top) an Avalon VT737, a Universal Audio 1176 Rev D, a Vintech X73i input channel, dbx 160X compressor, and an 1176 Rev A.It turned out that the ‘Wockesha’ mix session is a case in point, as it also is extremely simple. The beat is built around a sample of the 1983 DeBarge song ‘Stay With Me’, reinforced by producers Real Red, YC and Javar Rockamore with just four drum elements. With six vocal tracks, the mix session has only 11 audio tracks, not counting a 20‑second sample of Lil Wayne talking, and a couple of very short sound effects. But where some mix engineers rue that they cannot use more of their skills in such simple sessions, Morris takes a different view.

Morris’ outboard rack, featuring (from top) an Avalon VT737, a Universal Audio 1176 Rev D, a Vintech X73i input channel, dbx 160X compressor, and an 1176 Rev A.It turned out that the ‘Wockesha’ mix session is a case in point, as it also is extremely simple. The beat is built around a sample of the 1983 DeBarge song ‘Stay With Me’, reinforced by producers Real Red, YC and Javar Rockamore with just four drum elements. With six vocal tracks, the mix session has only 11 audio tracks, not counting a 20‑second sample of Lil Wayne talking, and a couple of very short sound effects. But where some mix engineers rue that they cannot use more of their skills in such simple sessions, Morris takes a different view.

“Yeah, this song is an immensely simple record. But aren’t the biggest records sometimes not the simplest? It’s the ones that don’t need all the extra shit that are the ones that cut through, because they really are good. With this record, the vibe was there, so it didn’t need a lot. When I received the session to mix, the track was already in a really special place, and Bagg was adamant that he liked the way the beat sat. So why do a lot?

“Generally, with all mixes I do, I get the track‑outs [stems of individual tracks]. But also in that case you need to honour somebody’s rough mix. It’s the name of the game now. People spend months sometimes on their rough mixes. There’s an intent there, and you need to enhance that intent. If something is really simple, you can say you’re over‑qualified, but really, there’s also an art to enhancing someone’s idea with a really subtle hand, without losing their vision.

“One of the things about a beat like this, where there are only five elements in the beat — sample, 808, kick, snare and hat — is that if you change the sonics of any of these, everything changes, and it’s a whole new piece of music. The minute you change anything, other than fixing something obvious, it falls apart. It’s not like when you’re working with a piece of music with 30 elements, and you can change the character of something, and nobody notices. So with a mix session like this, it’s all about being incredibly subtle. Mainly what I did was pulling in some midrange, using saturation and transformers, and mostly processing things together, because it means you’re adding an overall glue.”

Pro Tools Session View

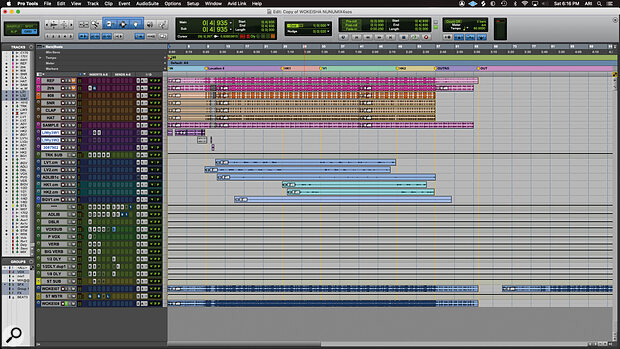

The Pro Tools Session view for Ari Morris’ mix of ‘Wockesha’.

The Pro Tools Session view for Ari Morris’ mix of ‘Wockesha’.

Download the ZIP file for a larger, detailed screenshot of the Session:

![]() inside-track-moneybagg-yo-screenshot.jpg.zip

inside-track-moneybagg-yo-screenshot.jpg.zip

Morris’ mix session for ‘Wockesha’ consists of 31 tracks. From top to bottom there are: the rough mix (REF), the two‑track of the beat, the five drum tracks (808, snare, clap, hat, sample), the Lil Wayne spoken word sample, the two sound effects samples, a submix track for the beat, six vocal audio tracks, a submix track for the vocals (titled ****), a submix track for the backing vocals (confusingly called ADLIB), a Doubler aux track with the Waves Doubler 2, two more vocal submix tracks, five aux effect tracks (two with reverbs and three with delays), Morris’ return track from his 5060, two mix print tracks and in between them a master track.

Although the aux tracks are arguably part of a template of sorts, Morris says he’s not keen on using templates. “I prefer to start with something like a blank canvas, other than that there’s some routing with a few key tools in there, but almost all plug‑ins are at factory default settings. Once I go into album mode, then yes, if the vocals for that album are all recorded in the same spot or similarly, I’ll pull similar vocal treatments across different mix sessions.

“Thankfully, with this album Moneybagg’s mix engineer cut everything with a Sony C800G, so there was a level of consistency. A lot of what I’m doing in other situations is bridging the differences between vocals recorded across multiple locations, multiple days or months or even years sometimes. You have to get creative to make those fit together.

“With Moneybagg I receive the Pro Tools session, and my assistant preps it, which is mostly a matter of colour coding and labelling stuff, so I know what I’m dealing with, and it looks the way I want my sessions to look. I can then just sit down and start mixing. I’ll listen to the rough a couple of times, and then I start running with it. I normally touch the music for a bit, then go to the vocals and work on them for a while, come back to the music, and back to the vocals.

“Once it gets to something that I think sounds good, I take a break, and when I come back I see where I’m at. Sometimes this means that I’ll pull everything down and start again. I learned to mix on analogue consoles, and a studio manager once said to me that a mix captures a moment in time. When you listen back later, sometimes it’s right, and sometimes it’s not. You stay in the moment, and don’t get mired in second‑guessing yourself. I’ll finish my thought, my moment, and there’s a risk that I sometimes later realise that I don’t like it.”

The Beat

Morris already explained above that he wanted his treatments of the beat to be very subtle, while ‘pulling in’ some midrange with saturation. For the beat in this session he does this on the Track Sub aux track.

“My signal chain on that track starts with parallel compression from the SPL IRON, hitting the Germanium side to add more weight. Next is the Oeksound Soothe. I love that plug‑in. It’s a genius piece. It just kinda softly curls under a couple of frequencies that I thought were a little too prominent, by probably half a dB. Then there’s the Gulfoss, which is another plug‑in that I like a lot for that low‑mid area. Next is the Ozone 8 Exciter, again bringing in some low mids, and the Mäag EQ4 has a sub‑bass boost and some high‑end air. The Kush Clariphonic EQ is doing a similar thing, putting some more shimmer on what’s happening.

“Working with various types of saturation is like putting a magnifying glass on certain frequencies, rather than straight adding them with EQ. At the same time, these EQs are very adaptable, and don’t feel as phasey to my ear as some regular EQs do. They don’t sit statically across the beat, but move with it, allowing me to be very subtle, in a way that nobody really notices. People just go, ‘Oh, it’s a little clearer and a little richer.’”

Vocals

The vocal group track, to which all vocal audio tracks are sent, and the AdLib aux to which the backing vocal audio track is sent, have very elaborate and almost identical vocal chains, consisting of FabFilter Pro‑Q 3, FabFilter DeEsser, Waves RCompressor, UAD Manley Massive Passive EQ, UAD dbx 160 compressor, UAD Thermionic Culture Vulture, and, in the case of the main vocal group, the FabFilter Pro‑MB and the Soothe 2, plus several aux sends.

“I used a few different vocal chains on this album, depending on the song and where the vocals were recorded. But in general it’s the same idea, with the Q 3 pulling out unwanted resonances, and the DeEsser just grabbing things at the top. The attack on the RComp is faster on the AdLib aux, to create a different character. I love the Manley, because you can add midrange without things going wonky. The 160 really crushes the vocals, something that I used to love doing on the hardware.

“The Culture Vulture is adding more weight and Pro‑MB is dipping some low end. With a husky voice like Bagg’s, it’s a delicate balance where his low end sits against the low end of the beat. There are also sends to the Doubler, and the reverb auxes, but on this song, I use them very minimally. Both vocal aux tracks are sent to the Vox Sub, which has the FabFilter Pro‑L 2, just kissing the signal a bit, a Mäag EQ4 for more air wizardry, and the Quartet DynPEQ also does great stuff on the top end. I parallel compress the Vox Sub, with the Waves 1176 on the P Vox track next to it.

Among the few new additions to Morris’ Memphis studio was the McDSP APB. Below it are two Burl B2 transformer‑balanced converters, through which Morris prints his mixes.

Among the few new additions to Morris’ Memphis studio was the McDSP APB. Below it are two Burl B2 transformer‑balanced converters, through which Morris prints his mixes.

“The Vox Sub and P Vox tracks, as well as all my aux effect tracks, are bussed out to the Neve 5060. Everything gets slammed in there, and again by my AudioScape bus Compressor, and via the Burl comes back to the Stereo Sub aux. The Burl has a stepped input transformer, which is nice for pushing stuff extra hard on coming back. It soft‑limits in a really nice way. The Stereo Sub track has the Black Box Analog Design HG‑2, again for more saturation, and I print the stereo mix next to it twice, once for the mastering engineer, and a second version after treatment by the Pro‑L 2, to push the volume up for my clients.”

In the end, Morris did get quite technical. But it’s the vibe and feel of his work that speak the loudest.

Mix Routine

Mixing A Gangsta’s Pain took Morris six months in total, off and on, and six weeks of continuous work at the end. Given that Morris says that mixing trap is all about vibe, how does he make sure that what gives him a particular vibe on one day gives him the same feeling on other days?

“When I’m really in crunch time for an album, I’m like an athlete in the play‑offs,” says Morris. “There are no haircuts, there’s no shaving, and there’s waking up, and breakfast and going to bed at the same time every day. I try to stick to the same daily routines every day, so it may be, ‘OK, we did the poke bowl from the grocery store today for lunch, I guess we’ll be doing it all week!’ As much as I can I control my environment and myself, so I’m very careful when I answer phone calls, and from who, and what energies I allow into my life during that period. Mixing is a game of mental fortitude, so I do what I can to stay in the same zone for the whole duration of a project.”