As if being in charge of the largest studio group in the world wasn’t enough, Miloco director Pete Hofmann also found time to mix the latest album from the UK’s biggest dance‑pop group, Steps.

“I wear lots of different hats,” explains Pete Hofmann. “I am one of the owners of Miloco, the largest studio group in the world. I’m Operations Director of the group and I oversee both the studios and the construction wing of the business Miloco Builds, and I suppose I have become the face of the business.

“At the same time, I also still try and carve out time to work as a mixer and I suppose ultimately stay relevant. I’ve been mixing for nearly 30 years, and for me mixing is my happy place. The few mixing projects that I do take on are for clients with whom I have worked a long time, and who I know and respect and who understand my other commitments. I do these things for the love of doing them, which is a lovely place to be. And I am very focused when I do music work.”

One wonders how Hofmann finds the time. The Miloco Group owns and/or does booking for a whopping 40 studios in London alone, and worldwide for studios in 47 locations. Hofmann’s parallel mixing career has also resulted in recent successes like mixing Will Young’s Lexicon (2019) and Steps’ What The Future Holds (released last November). Both albums went to number two in the UK.

In addition to his mixing work, Pete Hofmann is Operations Director for the international Miloco Group of recording studios.

In addition to his mixing work, Pete Hofmann is Operations Director for the international Miloco Group of recording studios.

Via Skype from one of Miloco’s London studios, Hofmann explains that the Steps mix situation was unusual, for several reasons. “My relationship with Steps is quite different from that with other clients, and not only because I have mixed for them for 15 years. Almost the entire album was programmed and produced by Jewels & Stone, aka Julian Gingell and Barry Stone, and when I work with them I mix directly in their production sessions. They each have their own studio, with identical Logic setups, so we can open their huge sessions on either of their computers, and the tracks can remain fluid until the moment they are bounced.

“While producing, one of them will work on the vocals while the other will concentrate on the music, and they can swap files all the time. That’s how they work. They take it to the point where they are more or less finished, with sessions that are very dense, containing many tracks and tons of plug‑ins. Inevitably things are clipping and hitting a wall, but it sounds hugely exciting. So my job as a mixer is to analyse what makes it exciting, and take all the good bits, and correct any bits that could be more ‘correct’, all while referencing their aspiration as to how they want the mix to sound.

“I will always listen to what has been given to me as a mixer, to understand what is good, and what needs improving. I will continue to reference what they did, because what I do has to be a progression. It is about being respectful to what people have done, and helping them make it better. Julian and Barry are writing musicians and producers, and for them I guess I’m like a safe pair of hands. I make sure every detail is correct. I bring my technical know‑how of 30 years of experience in what is correct.”

One of my main mentors was Charles Gray, who was the producer of Siouxsie and the Banshees. He was probably the most technical and gifted engineer I have ever worked with, to this day. He was an absolute scientist, and gave me all my grounding.

Stepping Stones

Pete Hofmann’s 30 years of experience began at Milo Studios, also known as The Square, in East London, in 1989. The studio was founded in 1984 by Henry Crallan and Queen bassist John Deacon. “I started as an assistant engineer, and my first session was with the Charlatans, working on their Some Friendly debut album, which is still one of my favourite albums of all time. I was 19, and really into the whole Britpop movement, so it was an amazing experience.

“One of my main mentors was Charles Gray, who was the producer of Siouxsie and the Banshees. He was probably the most technical and gifted engineer I have ever worked with, to this day. He was an absolute scientist, and gave me all my grounding. Over the years I worked my way up to chief engineer at Milo, and I became one of the studio’s biggest clients and was given the opportunity to invest in the company. Milo then joined up with one of my favourite studios, Orinoco Studios, to form Miloco. It grew into the family business it is today because we were a group of engineers and producers who took it on ourselves to save the studios that were closing in the late ’90s and ’00s. At one time our tagline was ‘Keeping studios alive in the 21st Century’.”

During his career, Hofmann has worked regularly with various producers, like Steve Hillage, Howie B and Luke Haines, and more recently Richard X. Hofmann’s credits, which are for engineering, mixing, producing and even the odd backing vocal, range from Black Box Recorder to Melanie C, the Pet Shop Boys, Kylie Minogue, Sheryl Cole, and Britney Spears. Over the years his credits have become notably more pop and dance orientated.

“I evolved with the music scene,” comments Hofmann. “But my favourites are probably Will Young’s Echoes (2011), which I co‑produced with Richard X and Jim Eliot, and Annie’s new album Dark Hearts [2020]. I think they are probably the best work I have ever done and they really reflect what was going on in my personal life at the time. I love an album with a concept. ”

Stomping Ground

Steps’ What The Future Holds falls squarely in the electro‑pop category, with the title song, written by Greg Kerstin and Sia Furler, a four‑to‑the‑floor banger with pulsating synth arpeggios and strong echoes of the ’90s. Hofmann explains that the album was mostly mixed at Miloco’s Elektrobank studio in South London. The studio was once known as The Toyshop, and was the Chemical Brothers’ studio in their early days (it takes its current name from third single of the Chemical Brothers’ classic album Dig Your Own Hole). Mix tweaks were done in the main room in the same complex, called the Red Room.

Hofmann notes that he is totally flexible as to where he works. “Twenty years ago I was mixing at Orinoco Studios. I used to love mixing there, and I used to love mixing on Neve desks. I was never really a big SSL fan, though I do have the SSL X‑Desk and now use the Sigma on the rare occasions I break out of the box. For most projects I’m mainly in the box, because it’s the quickest way of working and recalling. For me, time is my most precious asset! However, I still think that you get more harmonic interest from running signals through hardware, and you have to work a little harder to achieve the same thing in the box. So if you look at my Pro Tools sessions, you will find plug‑ins like the Cranesong Phoenix, Soundtoys Decapitator, Radiator and Devil‑Loc, and any kind of tape emulator. All the things that add harmonic interest.

I don’t get hung up on the tools I use. I’m a great believer in working with what you are given. Provided you know where you want to get to, it doesn’t matter how you get there!

“When you work fully in the box, where you physically work is less important. We’re now in a situation where you can have a fully loaded Pro Tools rig on a laptop. As an engineer, if you have the experience, and if you know exactly what you want the end result to be and you have the necessary tools, you can do great stuff. But I don’t get hung up on the tools I use. I’m a great believer in working with what you are given. Provided you know where you want to get to, it doesn’t matter how you get there!”

Steady Footing

While being very flexible about where he works and the tools he uses, Hofmann nonetheless recognises that “mixers like anchors,” which are a number of baseline parameters and tools they are familiar with. “For me they are like safety nets. For example, I always have the same plug‑ins on my mix bus. Years ago I used to carry around a Summit Audio EQP 200B for the hype, a Manley Vari Mu compressor for the air, and a GML 8200 parametric EQ for the surgery, to wherever I worked.”

Because he moves between studios a lot, another anchor that Hofmann likes is the Trinnov ST2 Pro loudspeaker/room optimisation unit. “When I am in a studio for the first time, I spend quite a lot of time listening to tracks that I know to try and understand the room. The Trinnov is a very useful tool for an engineer to carry around, and these days many studios have it. It is astonishing how it can sort out a room. It gives you that extra five percent of reliability, which probably would cost you £20k if you were to try to fix the room itself.

“As for monitors, I come from the generation of Yamaha NS10 and Genelec 1031 monitors, and I have many sets of both. But at Miloco, we now have five or six rooms with Augspurger monitor systems, and I love mixing on those. I know many people are sceptical, but the big plus is they sound incredibly accurate at low volumes and the imaging is superb. You typically have to drive big speakers hard to get them to work properly, and I don’t like to work at high volumes. But the ICE Class‑D amps the Augspurgers use are so powerful and just so fast, the detail they give at low volumes is astonishing.

“All the mixes I have done in the last few years were done on big monitors, and I only jump on the NS10s for tweaks and revisions. The thing is that it can be quite difficult when working in the box to get the bottom end right, particularly the pace. Just getting that engine working is a challenge. Many people get really bogged down trying to do that on nearfields, and then when they play back on another set of speakers, it sounds completely different. But on a pair of Augspurgers I get this right pretty quickly.”

Logic Gait

Having said all the above, when working with Steps, Hofmann was listening on Focal Twin6 BE and NS10 monitors, plus their trusty JBL Control 1s, which retail for £70 a pair, “because that is what Jules and Stone like to use and I’m fine with that. Also, Pro Tools is my DAW of choice, so working in Logic with them is a challenge, but one I enjoy. They’re actually still on Logic 9, with a 2009 TC Electronics Powercore effects unit. They are great believers in working with the tools with which they get results. If they’re having hit records, they’re clearly doing something right, so why change?

“I used to struggle working in Logic as a full‑time mixer, because I always felt that Pro Tools was much more pin‑point detailed. Working with Logic felt like trying to create a castle out of sand on the beach; it was like: ‘don’t touch it!’ However, Logic is very forgiving, you can make huge changes and you don’t really hear it or feel it, whereas in Pro Tools you hear tiny differences, like quarter of a dB changes. The thing I used to hate about Pro Tools, though, is that the more busing you did, the more latency you got, and suddenly the track didn’t feel right. There was this awful time when you would be second‑guessing and putting sample delays on tracks to try to bring the timing back together. Pro Tools 2020 seems a lot more solid, probably for the first time, but in truth Logic just works, which I think is the reason why so many people use it.”

There usually were a huge amount of tracks in each session, because all the inactive tracks are all still there, so for example with five singers all the pre‑comped takes may add up to 200 tracks.

When starting work on one of Jules & Stone’s Steps tracks, things were often complicated for Hofmann by the sheer number of tracks. “There usually were a huge amount of tracks in each session, because all the inactive tracks are all still there, so for example with five singers all the pre‑comped takes may add up to 200 tracks. It’s not like I’m working in a session that has already been condensed, which is normally the case when people send me stems. With these guys I get the session with all its nuts and bolts. So when I come in there is initially a lot of housekeeping involved.

“One important aspect of that is colour coding,” says Hofmann. “Blue is always drums, pale blue are special effects, bass is always red, guitars tend to be green, synths tend to be yellow, and vocals tend to be pink, but in the case of Steps, they are pink or blue, depending on whether you are a boy or a girl. That is my goto way of organising my screen. Orange is normally arpeggios.

“Also, Jewels & Stone run all synths live. On 'What The Future Holds' there may have been 200 synths, which never got printed. With them everything has to remain fluid. One of the album tracks was ready to be mastered when we got a call saying ‘Can you make it more flamenco?’ At that moment everything has to be reopened and everything has to be tweaked. This is another reason for working in the box. With these guys, we only print things when the computer starts struggling, in which case we will look for the most hungry soft synths. You would never be able to do this in Pro Tools, which falls over when you have more than 10 soft synths running live.”

One of the album tracks was ready to be mastered when we got a call saying ‘Can you make it more flamenco?’ At that moment everything has to be reopened and everything has to be tweaked. This is another reason for working in the box.

Approach To Mixing

Elaborating on his mix approach, Hofmann explains that his first hearing of any track he’s going to mix is crucial. “The first time they play me the track I will be making notes. I’m writing down my first impressions, the things that I know straight away are wrong and the things that I know could be better. Literally on the first listen I will write down everything that I hear that needs correcting, which always is very obvious to me. Later during the actual mix I work my way through that list.

“I’ll then play the tracks one by one. I can take in quite a lot of information quite quickly, so I go through the tracks to understand what is doing what. After I have muted everything I start putting things back in track by track, to understand where I can make space.

“I’ll then play the tracks one by one. I can take in quite a lot of information quite quickly, so I go through the tracks to understand what is doing what. After I have muted everything I start putting things back in track by track, to understand where I can make space.

“Ninety‑nine percent of the time I will start the actual mix by working on the drums, and I will finish with the bass. I get my drum sounds right, then I get the bass sound, then I take the bass out, and put everything else in, and then bring the bass back at the end.

“That is the way I always used to work on a console. I think it comes from working with bands in the late ’90s. The bass takes up so much room it can often be a bit distracting. You want the space to hear what is happening in the midrange with the guitars and vocals. Taking the bass out, and then bringing it back in at the end, gives you the space to hear what is going on in the midrange. Obviously, it does not work for everything. I don’t really work like that in electronic and dance music, because the kick and the bass together are so integral for the entire movement of the track. Getting the kick and bass right is a dark art, but some people do it amazingly well.

“Mixing dance music is not only about the bass and drums, but also about the headroom. It’s a matter of making sure that the bass and the kick are not too wide, that there is enough headroom for mastering, and at the same time keeping the excitement of what they achieved by hitting the buses really hard. This is about gain‑staging. If you look at the faders in the session for ‘What The Future Holds’, you will see that many tracks are at ‑12 or ‑16, because the source audio is too hot. On the other hand, the fact that it is distorting a little bit is helping the excitement.

“I do a lot of bit crushing, and then add really minimal stereo delays, so you get these intense fuzzy delays, and you bring in a little bit of that underneath the main signal. That really helps. I guess it is a little bit like using an Aural Exciter, with the sort of busy excitement that you can slot into a mix. It makes the sound more exciting without turning it up. I always imagine mixes as if they are kind of like a bonsai tree. It is all about the bottom end being really solid, and then the exciting stuff, especially in pop music, happens in the top end and the high mids. How you do that depends on your palate in how far and wide you want to push the detail. I spend a lot of time on that. I use the Brainworx bx_digital v2 plug‑in a lot for this. I’ll often use it at 120 percent from the moment I’m starting a mix, and I’ll be very aware of how wide things are going. It’s like setting the width of your canvas.”

The Mix

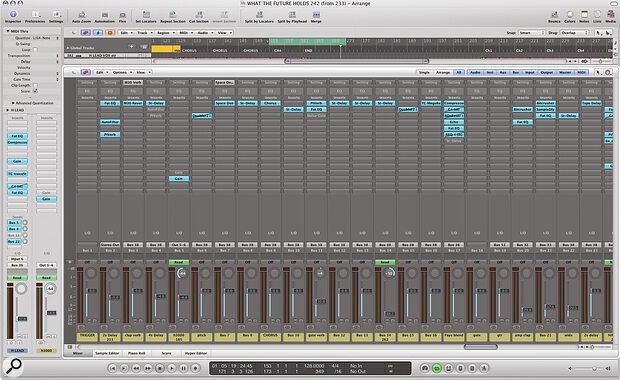

Pete Hofmann talks us through the mix for ‘What The Future Holds’: “Jewels & Stone often start from a template that we have probably used for 10 years. The template contains a number of effects tracks, which are pretty generic; the first 20 buses are probably the same effects on every project that we do. In this session they are at the bottom, as well as all the instrument and vocal buses. This is the meat of the session, where I do most of the work.

For his mix of ‘What The Future Holds’, Hofmann worked directly in the Logic 9 project used by production duo Jewels & Stone.

For his mix of ‘What The Future Holds’, Hofmann worked directly in the Logic 9 project used by production duo Jewels & Stone.

“The first bus is the Trigger track, for side‑chaining. With a four‑to‑the‑floor dance track like this, there’s a lot of side‑chaining going on. The bass, all the synths, even the vocals, will be side‑chained to the kick. In club music it is all about making space for the kick and controlling the pace, so it can be where it needs to sit, and everything else sits around it. In Logic I use the Factory plug‑in for side‑chaining, and I vary the modes, in Pro Tools I just use Impact.

“The next buses are a delay, clap reverb, and one called H3000, and it actually goes to an outboard unit, the only one I used. The Eventide H3000 does something that nothing else does. It’s always set to the Breathing Canyon preset. Next are a Waves Doubler, stereo delay, chorus, another delay, a reverb, three more tracks with delay throws, another doubler, a TC Powercore bus, a widener, and so on. Most of these are Logic plug‑ins, with a few Waves and a little bit of TC Electronic. I tend to use many more delays than most people use. I will use very short delays to thicken things, or if I want to widen sounds, I will use like a 25‑30 ms delay, as a stereo thing.

“After the aux effect tracks are the group tracks, with Kick, Drums, Bass, Keys, Pads, Vox, BVs, Logic FX, and before that Rhythm Guitar, Intro, more backing vocals, and so on. With club music I always have the kick on a different bus than the drums. The main vocal bus has many plug‑ins, amongst them the Waves Renaissance de‑esser and Waves C1 compressor. The actual audio tracks usually have only a little bit of the Logic Fat EQ and Logic compression on them, and some of the tracks have sends to the aux effects buses.

“With Steps, the vocals tend to be recorded quite quickly, so each vocal will be automated quite heavily. They all use the same mic and signal chain. I also do a lot of EQ automation, to make sure the tone of all the vocals is consistent before it goes into the mincer of the master vocal bus. I want to make sure that they all occupy exactly the same space in the mix for the duration of the track. It is as much about how they each are presented as about how they sound. They then all go to a group bus, on which I will often strap a reverb as an insert to slot them into the mix and vary the ‘focus’.”

Pete Hofmann: Mixing dance music is not only about the bass and drums, but also about the headroom.

On The Bus

Hofmann mentioned earlier that his master bus chain is one of his anchors. He elaborates about his current in‑the‑box chain: “The bx_digital v2 is always first, for EQ and mono summing everything below 200Hz, a little bit of de‑essing, just to grab some top end of snares and effects that I have not managed to grab in the mix. After that the PSP Vintage Warmer 2 makes an appearance, because that is where the harmonic excitement comes from. I drive it pretty hard, with the Mix set between 10 and 30 percent.

“Next is the Slate Digital Virtual Tape Machines. I have used many tape emulators, I actually like the Slate one. I normally end up with a different combination of tape, speed and biasing for every mix, because it all comes out different. I have it very early in the chain, because for some reason it does really bizarre things to the bottom end. After that I have the Pultec EQP‑1A, to add that magical high end. Just add 3dB at 16kHz and let it do its thing — that’s a Mike Spencer trick.

“I also used the TC Electronic Master X HD for multiband compression. Quite a lot of the fizzy excitement comes from that and it’s the sort of thing that if it has been on during the writing and programming, the mix won’t work without it. I have been a fan of TC multiband compression since the M5000, which was the first time I experienced digital multiband compression. I used that box so much for a period of time, it was a mix fixer. Nowadays I tend to use the McDSP ML4 instead of the M5000, and there’s also a limiter called the DMG Audio Limitless, which I really like for multiband. I currently tend to have the Limitless at the end of my chain, which is basically doing the same thing a mastering engineer would do.”