This month’s featured artist is Jeff Hirata (https://linktr.ee/jeffhirata) with his song ‘Sunshine’.Photo: Katie Sambala, Kap2ure Creative Company

This month’s featured artist is Jeff Hirata (https://linktr.ee/jeffhirata) with his song ‘Sunshine’.Photo: Katie Sambala, Kap2ure Creative Company

Ever thought you were nearing the end of your mix, only to realise the track needs a whole lot more impact?

How do you add energy to a mix? I mean, I imagine that every DAW user has at one time or another been faced with a project where they’ve gone through all the usual mixdown motions, but ended up with a result that feels somehow a bit lacklustre, plodding, and generally uninspiring. In other words, it lacks energy. And in my experience, it’s this malaise that most commonly leads SOS readers to approach the Mix Rescue column. With that in mind, I’d like to focus this article on a mix overhaul I recently did for singer‑songwriter Jeff Hirata, where I applied a variety of different techniques I’ve learnt over the years for enhancing this rather intangible mix quality.

Energetic EQ

When Jeff sent me an MP3 of his song ‘Sunshine’, he was already well aware that his mix didn’t feel as exciting as he’d hoped, given the cheery musical content. But he was stumped about how to improve matters. When he added more low end, or more compression, or extra guitar layers, it just made things muddy and sacrificed clarity. When he pushed the drums up in the mix, the sound became too aggressive and lacked cohesion. When he tried boosting brightness it just made the overall sonics abrasive and fatiguing. More insidiously, though, he just felt that the mix was making the music seem almost boring, despite what I agreed was solid songwriting and a decent set of performances.

Now, Jeff wasn’t wrong by any means in reaching for the mix tools he did, but in each case the problems he was addressing ran a little deeper than he’d identified. Take the idea of boosting the low end, for instance. In principle, this is a great way to make a mix sound more exciting, but there were two good reasons why I was able to do this in my remix where he’d previously struggled. Firstly, I cleared space for low‑end boosts on the kick drum and bass guitar by filtering out low end from more than a dozen other tracks: drum overheads, drum room, low tom, congas, steel pans, acoustic/electric guitars, and backing vocals. And, secondly, I realised that the fundamental frequencies of Jeff’s bass‑guitar part seldom strayed below 50Hz, which left plenty of free mix real‑estate for me to add a sneaky programmed sub synth layer. So, yes, more low end on your kick and bass will usually translate into a more exciting mix, but only if you plan enough space in the spectrum for that to fit.

Likewise, Jeff was right that brightening a mix often makes it feel more urgent and immediate, but you need to work in a targeted manner. So while I certainly brightened my remix with high‑frequency EQ boosts and saturation effects, I was able to avoid the harshness problems Jeff had originally encountered, by:

- Filtering high end out of less foreground parts, such as the hi‑hat and hand percussion.

- Softening fatiguing upper‑spectrum transients with low‑pass filtering (for the kick), clipping (for the snare), limiting (for the tambourine), and multiband limiting (acoustic guitars).

- Rebalancing overprominent noise consonants and sporadic high‑frequency resonances on the (numerous!) vocal parts with de‑essing, multiband compression, specialist spectral compression (from ProAudioDSP’s DSM plug‑in), and region‑specific EQ processing.

Here you can see various different processes Mike used to add brightness to Jeff’s mix without making it sound harsh at the same time: cutting high frequencies from the hi‑hat with Cockos’ freeware ReaEQ; smoothing the tambourine transients with Dead Duck’s freeware Limiter; de‑essing backing multiple vocals with Dead Duck’s freeware De‑esser; and controlling the lead vocal’s upper‑spectrum consonants and resonances with Pro Audio DSP’s DSM spectral processor.

Here you can see various different processes Mike used to add brightness to Jeff’s mix without making it sound harsh at the same time: cutting high frequencies from the hi‑hat with Cockos’ freeware ReaEQ; smoothing the tambourine transients with Dead Duck’s freeware Limiter; de‑essing backing multiple vocals with Dead Duck’s freeware De‑esser; and controlling the lead vocal’s upper‑spectrum consonants and resonances with Pro Audio DSP’s DSM spectral processor.

Lively Dynamics

Jeff’s impulse to lean on his compressors had something going for it too, because compression can indeed add liveliness and movement to the musical balance. But the catch is that compressing the wrong things or dialling in the wrong settings can just as easily kill a mix stone dead! My main advice here is not to get too carried away with per‑track compression settings (where you run greater risk of compromising the musicality of each individual part), and focus more on compressing ‘ensemble’ signals. So in my remix, for example, I had no compression at all on any of the software drummer’s individual instrument channels, but instead compressed the drum room mics, the drum kit submix, the main mix bus, and a drums parallel channel. These compressors introduced subtle music‑related level interactions between each drum and the rest of the arrangement, thereby providing a more energetic‑sounding mix without a loss of musicality — as well as an increased illusion of ensemble cohesion into the bargain!

No compressor is intelligent enough to consider lyric intelligibility or melodic phrasing — all it sees are signal levels.

But however you decide to use compressors for your mix, it’s vital to understand their limitations, so you don’t expect them to deal with mix‑balance problems they can’t reasonably be expected to handle. Nowhere is this more important than with lead vocals, where no compressor is intelligent enough to consider lyric intelligibility or melodic phrasing — all it sees are signal levels. In my ‘Sunshine’ remix, for instance, I had plenty of compression on Jeff’s vocal (a chain involving a fast limiter, a slower compressor, and a fast parallel compressor), but while that certainly helped give the performance a subjectively assertive attitude, it was actually my detailed fader automation that consolidated its place in the mix balance and ensured that every word cut through clearly.

Automation is also crucial for breathing life and humanity into the mix balance as a whole. You see, one of the things that makes a production seem engaging is if listeners are constantly alerted to new and interesting facets of the musical material. By simply going through your arrangement and turning up the most interesting moments, you’ll actually make the music itself seem better, as well as generating the illusion that all the musical performers are communicating with each other organically — even if everything was actually programmed and overdubbed one track at a time! As such, it should be no surprise that this kind of automation played an enormous role in my remix of ‘Sunshine’, where I did detailed fader rides across at least 20 tracks.

Although a good deal of compression was used to add energy to this remix, it was detailed automation that was responsible for solidifying the final mix balance.

Although a good deal of compression was used to add energy to this remix, it was detailed automation that was responsible for solidifying the final mix balance.

Widescreen Imaging

Although Jeff highlighted EQ and dynamics processing as potential sources of mix hype, the concept of stereo widening didn’t really make it onto the radar as much, beyond double‑tracking the guitar and vocal parts to allow for opposition panning. Yet, a broad panorama is one of the most reliable ways to make almost any mix feel more vibrant and impressive. Not that I’d recommend just slapping some kind of stereo doohickey over the master bus, because widening treatments tend to work best, in my opinion, when you carefully select the specific tracks you’re going to widen and use different widening tactics for different instruments.

So in my remix, for example, I avoided extreme widening of any of the production’s most important musical elements (kick, snare, bass, rhythm guitars, lead vocals), so as to avoid compromising their mono compatibility. For percussive parts, I decided to use simple Mid‑Sides processing or EQ‑based widening to avoid any of the undesirable rhythmic flamming associated with delay‑based patches, whereas on vocals I was happy to benefit from the gentle thickening side‑effects of pitch‑shifted micro‑delays.

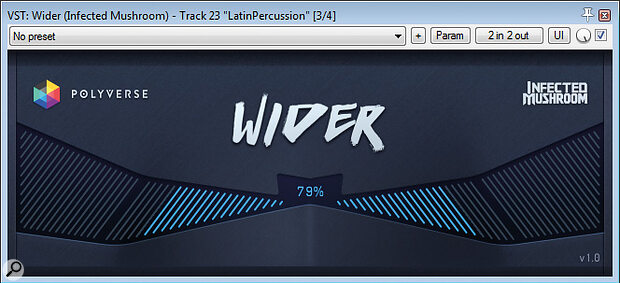

For stereo widening, Mike used a combination of traditional M‑S‑based processing from Voxengo’s freeware MSED and EQ‑based widening from Infected Mushroom’s freeware Polyverse Wider.

For stereo widening, Mike used a combination of traditional M‑S‑based processing from Voxengo’s freeware MSED and EQ‑based widening from Infected Mushroom’s freeware Polyverse Wider.

Laws Of Layering

Another method Jeff had used to power up his mix was layering, and by the time he sent his multitracks to me they were swimming in rhythm‑guitar and backing‑vocal tracks: more than 50 tracks in total! There’s no question that layering’s a widespread technique for mainstream pop‑rock songs like this so his heart was in the right place, but you can easily have too much of a good thing in this respect.

With electric guitars, an ever‑present concern is that layering multiple recordings of the same guitar sound can quickly smooth out the crunch and character of each individual part into a chorusey ‘background blancmange’. This is why I deliberately avoided layering more than two tracks of any given guitar sound together in my remix, and even in those sections where two or three pairs of electric guitars were playing together, I made a point of differentiating their timbres (in one case reamping one of Jeff’s supplied DI parts with my own amp simulator plug‑in) in order to retain some clarity and definition. I followed the same tack with the backing vocals, jettisoning anything beyond a double‑track for each harmony line. I then also supplemented Jeff’s recordings (all of which featured his own voice) with new layers that my daughter and I recorded, thereby expanding the subjective size of the ensemble more convincingly.

No matter how epic your layered texture, however, there’s a limit to how long it’ll impress the listener. For better or worse, we humans lose interest in that kind of thing quite quickly! This is one of the reasons, in fact, why less experienced recording musicians tend to record too many layers, because the texture always seems to sound best just after each new part has been added, but that psychological buzz naturally fades with time. So, from a mixing perspective, it’s wise to vary the layering for any repeated song sections (eg. the choruses) in order to give each iteration enough novelty to maintain the listener’s interest. And this process offers another golden opportunity to ratchet up the mix’s energy levels by muting/rebalancing the layers to enhance the feeling of build‑up. Here’s how I did this in my remix, for instance, by modifying the guitar layering in each successive chorus:

- Chorus 1: A mono muted rhythm part on acoustic guitar, and four‑layer stereo electric guitar accents.

- Chorus 2: The acoustic guitar part changes to two‑layer stereo, and the electric guitars are EQ’ed for more warmth.

- Chorus 3: Two‑layer acoustic guitars and four‑layer electric guitars move to rhythmic strumming, with support from two‑layer electric‑guitar accents.

- Chorus 4 (breakdown following the climactic middle section): Four‑layer acoustic guitars and six‑layer electric guitars all play one strummed chord per bar.

- Chorus 5: The bass is muted, the muted rhythm part returns on stereo two‑layer acoustic guitar, and supporting accents are provided by two layers of acoustic guitar and four layers of electric guitar.

- Chorus 6: The bass returns, with four‑layer acoustic guitars and four‑layer electric guitars moving to consistent strumming while a further two layers of electric guitar provide accents.

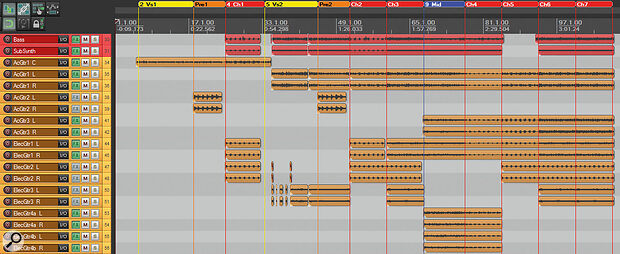

Not only does this arrangement avoid the listener ever having to experience the same chorus sound twice, but it also helps create a powerful momentum towards the middle section in the first instance, and then towards the final choruses after that. And if you look at the screenshot of my vocal arrangement, you can see a similar trajectory there, with the chorus texture progressively thickening in two ‘intensity ramps’ (just like the guitar arrangement does), as well as providing an extra lift for chorus seven, given that the guitar texture has already maxed out by then. Now, I realise it can be difficult to imagine how this all sounds from just the text and pictures here, so I’ve created some special demonstration videos at www.cambridge-mt.com/jeffhirata in which I deconstruct my remix’s guitar and vocal arrangements in detail to show how each layer sounds, and how all the layers fit together in conjunction with the lead vocal and its changing delay/reverb effects.

There are many other ways of adjusting the arrangement to energise a mix, however. The easiest is just to flex your mute buttons so that the listener gets a better opportunity to appreciate the qualities of each track. So, in my remix, I started with just acoustic guitar and lead vocal, whereas Jeff’s original mix already featured snare drum and steel pans right at the outset. Your mute buttons can also add drama by suddenly refocusing the listener’s attention on something new, for example where I dropped the drums out abruptly at the end of the first chorus to highlight the re‑entry of the chorus vocal, acoustic guitar, and shaker.

The ‘Wow’ Factor

Taken together, these tricks were already doing a pretty good job of presenting Jeff’s recorded material in a much more engaging light, but it was apparent from our initial discussions that he’d heard some of my more extensive Mix Rescue transformations, and was keen for me to push into more creative territory if I felt it might elevate things further. With this in mind I found myself pondering what to do about the middle section. The problem was that the music seemed to demand some kind of ‘step up’ in the arrangement energy from the preceding chorus section, but there were no new musical parts at that point from which to conjure this extra impetus.

So my thoughts turned towards the idea of recording something new myself. This is where you can quickly get into trouble as a third‑party mix engineer if you’ve not adequately established ground rules for such experimentation — I’d suggest the maxim “If you hate anything I’ve added, I’ll take it out without question” as a good place to start! But even in a situation like this, where the artist has actively solicited creative input, it’s important to have a clear rationale for any additions you make. In this case, my thought process went something like this:

- I want a part that sits in the upper pitch registers, because the low end and low midrange are already saturated with the bass and guitars in that section of the song.

- I should probably avoid anything that’s too noisy or rhythmic, otherwise it might interfere with the lead vocal’s intelligibility at a point in the song where Jeff’s singing fresh lyrics.

- The guitar parts become a little more sustained during the middle section compared with the preceding chorus, so I’d like to add something that emphasises that contrast.

- It’d also be nice to add something with a bit of ‘wow’ factor to help Jeff fall back in love with his own song after so much frustration during his own initial mix process.

If I’d only had to address the first three of these considerations, I’d probably have fallen back on that old stalwart, the Hammond organ pad — just tweak the drawbars to funnel the frequencies into your mix’s spectral pockets, add some tasty swirl by automating the Leslie speaker’s speed switch, and Bob’s your uncle! But that didn’t feel like it would be a dramatic enough move to really blow the lid off this particular section, so I resolved to take a riskier route.

Taking my inspiration from one of the songs Jeff and I had referenced during our initial discussions (the Rembrandts’ ‘I’ll Be There For You’), I returned to the vocal microphone and layered up some new sustained four‑part backing‑vocal harmonies based on the word “Sunshine”. (Never a bad idea to reiterate the title hook!) Then, realising that this same sustained harmony‑vocal sound also seemed to work quite well for the second and third groups of choruses, I added some similar layers there too, while being mindful of the need to weed out a few layers earlier in the song, so that the arrival of the middle section still made enough of an impact.

These two screenshots show the final acoustic/electric guitar and backing‑vocal arrangements from Mike’s remix of ‘Sunshine’. As you can see, the arrangement is designed to build up in two ‘ramps’, the first culminating in the middle section, while the second culminates in the final choruses. Notice also that, as part of this, no verse or chorus has exactly the same arrangement as another, which helps maintain the listener’s interest throughout the production’s timeline.

These two screenshots show the final acoustic/electric guitar and backing‑vocal arrangements from Mike’s remix of ‘Sunshine’. As you can see, the arrangement is designed to build up in two ‘ramps’, the first culminating in the middle section, while the second culminates in the final choruses. Notice also that, as part of this, no verse or chorus has exactly the same arrangement as another, which helps maintain the listener’s interest throughout the production’s timeline.

Harness The Energy

There are a lot of different tools that you can use to boost the sense of energy in your production: EQ, compression, automation, stereo widening, editing, layering... but each of those things can also work against you if you’re not careful! I hope this real‑world case‑study has provided some pointers for getting the best out of them in practice.

Structural Cuts

In addition to the arrangement adjustments discussed in the main text, I also made a couple of structural changes. Like a lot of project‑studio song productions, the song opened with an instrumental intro that was basically just treading water on the verse chord progression and, from a singer‑singwriter’s point of view, that’s rarely the best use of the audience’s first 10 seconds of attention! So I decided to replace the preamble with just a little guitar fill, and bring Jeff in right from the outset to begin telling the song’s story and building that all‑important personal connection with the listener.

Likewise, I saw no reason to keep a very similar instrumental section between the end of the first chorus and the beginning of the second verse. All it seemed to be doing was smoothing out arrangement differences between those two song sections, which seemed counterproductive given how effectively an abrupt textural change at this point in a song can grab the ear for the second round of verse lyrics. Again, I just excised this section, as well as further thinning out the beginning of the second‑verse arrangement to make even more of a virtue of the section contrast.

Timing Edits

With any upbeat song like this, tightening the timing and tuning can have a powerful impact on how cheerful and bouncy the mix sounds. For this project, it was the timing that demanded the most work, and for two reasons:

- Firstly, although Jeff’s playing wasn’t particularly wayward, he was playing against programmed drums, whose rhythmic implacability tends to throw even small groove discrepancies into higher relief.

- Secondly, many of the rhythm parts were layered, so even minor rhythmic disagreements between layers were blurring the layered note onsets and reducing the punchiness of the combined texture.

As usual, my first process involved conforming the bass with the drums while all the guitars were muted, and then reintroducing the guitars layer by layer to refine their timing against the bass/drum foundation by ear.

Online Resources: Audio Clips, Videos, Mix Project & Multitracks

As usual, I’ve provided a selection of audio examples to accompany this article (including the full‑length ‘before’ and ‘after’ mix versions) on the Sound On Sound website at https://sosm.ag/mix-rescue-0323. In addition, though, I’ve created a special resources page at www.cambridge-mt.com/jeffhirata where I’ve posted several demonstration videos including:

- Track‑by‑track deconstructions of my remix’s vocal and guitar arrangements.

- A detailed explanation of my synth sub‑bass setup.

- A full mix playthrough highlighting my use of fader automation on the different tracks.

You’ll also find download links for my complete Reaper remix project (with a folder of screenshots so you can scrutinise my settings in detail) and for the song’s raw multitrack files in case you fancy trying a remix of your own!

Remix Reaction

Jeff Hirata: “Wow, Mike, you did an absolutely incredible job! When I first heard the mix I was honestly shocked to hear how amazingly happy, bright, and exciting the song had become. It’s a dream come true — I can finally turn the song all the way up in my car to rock out, and also turn it all the way down and still hear everything clearly. The main vocals are the most important part of the mix and are done to perfection, but my mind was absolutely blown when I heard how you’d used the background vocals to uplift the song to a whole new level! They add a richness and complexity that a professional mix should have, while also introducing the sense of lightness and fun that the song was so desperately missing. The bridge used to be my least favourite part of the song, but with the backing vocals it’s now something I look forward to! You did hundreds of other little things that also added up, like removing the snare drum from the beginning, and more slowly building up the drums. It’s one of those things you hear and wonder why you never thought of it yourself, since it made so much sense after hearing it!”