Ever wondered why your beats can't compete with commercial mixes? We show you how to nail them... without losing sight of the song.

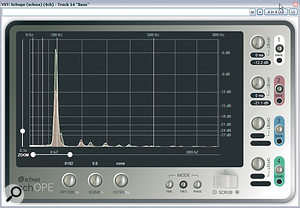

The leftmost of these three frequency plots shows the rough frequency balance of Chris's original bass part, which lacked low‑end power and was also getting lost in the mix. You can see that the pronounced fundamental frequency is quite high (around 100Hz), and there's minimal mid-range energy. The second plot shows the same track, which Mike rebalanced with high‑frequency EQ boosts and multi‑band compression to lift the mid‑frequency energy and make the sound cut through more audibly. A sub‑bass synth was then layered an octave below this for extra low‑end power, and the final frequency plot here shows how the frequency content of that was tailored to only supplement the low end.

The leftmost of these three frequency plots shows the rough frequency balance of Chris's original bass part, which lacked low‑end power and was also getting lost in the mix. You can see that the pronounced fundamental frequency is quite high (around 100Hz), and there's minimal mid-range energy. The second plot shows the same track, which Mike rebalanced with high‑frequency EQ boosts and multi‑band compression to lift the mid‑frequency energy and make the sound cut through more audibly. A sub‑bass synth was then layered an octave below this for extra low‑end power, and the final frequency plot here shows how the frequency content of that was tailored to only supplement the low end.

When Chris Durban sent in his song 'Celebrate' to SOS, he shared with many former Mix Rescue candidates the complaint that his mix was feeling bogged down and lacked clarity. However, his other main concern was that the drums were sounding loose and weren't driving the track along — a serious drawback for a dark, moody dance tune like this. I've written on a number of occasions about strategies to reduce clutter in your mix, so rather than dwell on that again this month, I've decided instead to focus on how I dealt with the central issue of Chris's rhythm sound. Hopefully, in the process I can pass on some tricks that will be of benefit to anyone working in these kinds of styles.

In addition, I'm also going to look in detail at a couple of situations where triggering dynamics processors via their side‑chains really paid off in this mix. This is an engineering tool that can untangle some of the toughest mix conundrums, so it makes sense to discuss it while the examples are to hand!

Kick & Bass: Fighting For The Low End

While adding in the sub‑bass synth layer underneath Chris's original bass synth line, Mike took the opportunity to improve the groove by making the programmed addition more rhythmic and punchy. You can see here how the sub‑bass line (below) is right on the beat grid, where the original line has a fairly vague rhythmic outline.

While adding in the sub‑bass synth layer underneath Chris's original bass synth line, Mike took the opportunity to improve the groove by making the programmed addition more rhythmic and punchy. You can see here how the sub‑bass line (below) is right on the beat grid, where the original line has a fairly vague rhythmic outline.

With most dance tunes (and 'Celebrate' was no exception), the most important elements of the mix are the kick and bass parts, so that was where I started my remix. Listening to these two raw tracks together, it was immediately apparent that the kick was much too distant and woolly to drive this kind of rhythm along, but there were also other, less obvious, problems. The first was that the bass sound was rich in frequencies in the 100Hz region, but had very little going on below that, while the kick provided more balanced contributions in both these regions. Neither part really filled out the low end in the way I'd have expected for this kind of style, however, so I had to decide how I was going to do this.

When you're making bass and kick drum fit together in a mix, it often makes sense to focus the low end of each into a separate area of the spectrum, so that they don't compete with each other for mix headroom in the same frequency range. With this in mind, the kick drum should, in theory, have been the better contender to take the lower regions of the mix, given a stiff shot of EQ to boost its LF components. However, on a musical level this didn't really make sense to me, because the kick‑drum needed the definition to articulate its fast hit pattern, and instruments with lots of very low frequencies aren't too good at doing this; the result you get if you try is usually just a mushy rumbling going on underneath your kick pattern, bogging it down and making it less punchy.

To give the overall drum sound more aggression, Mike mixed in a parallel‑processed signal, combining fast, heavy compression from Stillwell Audio's The Rocket compressor and some tube saturation from Wurr Audio's Tube Booster.So I decided to take a different route, and instead use the bass line to underpin the track. As I've already mentioned, though, this line didn't have much going on below 100Hz, which meant there was no option but to synthesize the lower frequencies artificially. There are a number of ways to do this in a mix with processors (such as by using MDA's freeware SubSynth utility), but I prefer, where possible, to add in a separate synth line, so that I have maximum control over the added frequencies. As usual, I didn't use anything fancy, just Reaper's no‑frills ReaSynth plug‑in set to output a triangle wave. I then gently rolled off the upper frequency spectrum above 100Hz with the low‑pass filter in Reaper's ReaEQ, to leave mainly just sub‑bass information.

To give the overall drum sound more aggression, Mike mixed in a parallel‑processed signal, combining fast, heavy compression from Stillwell Audio's The Rocket compressor and some tube saturation from Wurr Audio's Tube Booster.So I decided to take a different route, and instead use the bass line to underpin the track. As I've already mentioned, though, this line didn't have much going on below 100Hz, which meant there was no option but to synthesize the lower frequencies artificially. There are a number of ways to do this in a mix with processors (such as by using MDA's freeware SubSynth utility), but I prefer, where possible, to add in a separate synth line, so that I have maximum control over the added frequencies. As usual, I didn't use anything fancy, just Reaper's no‑frills ReaSynth plug‑in set to output a triangle wave. I then gently rolled off the upper frequency spectrum above 100Hz with the low‑pass filter in Reaper's ReaEQ, to leave mainly just sub‑bass information.

I could have simply carbon‑copied Chris's bass line, but instead I took the opportunity to address another musical concern I had with the line as it stood, namely that the particular modulated bass synth Chris had used seemed to me to be undermining the overall rhythmic pulse of the track as a whole. My course of action, therefore, was to make my sub‑bass part more punctuated and obviously rhythmic, to better support the groove. Into the bargain I also lightly processed Chris's bass part with a gate (keyed via its side‑chain from the new sub‑bass part), so that it too followed those new dynamics a little.

Punch & Clarity

A couple of thick‑sounding synth and electric guitar parts were really clogging up the mix in the choruses, so Mike chopped them up into slices and used only the most interesting of these in order to claw back some space.

A couple of thick‑sounding synth and electric guitar parts were really clogging up the mix in the choruses, so Mike chopped them up into slices and used only the most interesting of these in order to claw back some space.

Once I'd worked out a fader balance for the three primary sources of low frequencies, I turned my attention to the timbre of the kick and bass sounds as a whole. I really wanted to harden up the kick sound, so tried emphasising the drum's initial transient with a couple of transient‑shaping plug‑ins in series: Stillwell Audio's Transient Monster and Reaper's Jesusonic Transient Controller. Each manufacturer's version of this kind of process sounds different to me, and I'm increasingly finding that I'm chaining more than one such plug‑in to combine their unique attributes.

The extra transient punch helped a good deal, but robbed a bit too much bass from the resultant signal, so I switched in Stillwell Audio's Vibe EQ to add a compensatory 5dB low‑shelving boost at 60Hz. Knowing how important it would be to get this drum sound to punch through the mix, I also experimented with boosting using Vibe EQ's peaking bands around the 1‑3kHz region, a range that is clearly audible even on smaller speakers and iPod earbuds. However, this didn't deliver the extra edge to the drum's attack that I'd hoped for, and it also brought up some decay elements of the drum sound that I wasn't too fond of. Some kind of multi‑band transient processing might have helped here, but I opted again for the more controllable approach of layering a separate sample on top of the kick drum. Triggering this was easy‑peasy with Reaper's MIDI‑enabled ReaGate plug‑in, because the kick‑drum sample that Chris had used was completely without dynamics. All that remained to do was to select an appropriate sample (a snare drum, as it turned out!), truncate it to isolate its attack transient, and then layer it in at a suitable level.

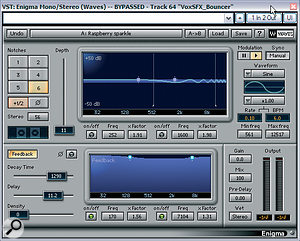

Additional special effects within this mix came courtesy of Waves Enigma, Schwa Tin Man, The Interruptor Echomania, and Tin Brooke Tales Tape Stop.The bass sound that Chris had chosen was still very dull‑sounding, and as soon as I started adding in the synths and other vocal parts this lack of definition made it very difficult to keep the sound clear in the mix. For this reason, I gave the part a royal mangling to dredge up any and all of the signal's high‑frequency information: big 12dB peaking boosts at 2kHz and 9kHz with the Smartelextronix Nyquist EQ (a plug‑in that copes quite well with HF boosts) followed by low‑threshold 2:1‑ratio multi-band compression from Reaper's ReaXcomp. The processing was so heavy that I might as well have added a new synth layer, but it worked much better at keeping the bass‑line melody audible against the rest of the tracks. It's surprising how much you can get away with changing synth sounds through processing, because no‑one but you knows what the source recording actually sounded like!

Additional special effects within this mix came courtesy of Waves Enigma, Schwa Tin Man, The Interruptor Echomania, and Tin Brooke Tales Tape Stop.The bass sound that Chris had chosen was still very dull‑sounding, and as soon as I started adding in the synths and other vocal parts this lack of definition made it very difficult to keep the sound clear in the mix. For this reason, I gave the part a royal mangling to dredge up any and all of the signal's high‑frequency information: big 12dB peaking boosts at 2kHz and 9kHz with the Smartelextronix Nyquist EQ (a plug‑in that copes quite well with HF boosts) followed by low‑threshold 2:1‑ratio multi-band compression from Reaper's ReaXcomp. The processing was so heavy that I might as well have added a new synth layer, but it worked much better at keeping the bass‑line melody audible against the rest of the tracks. It's surprising how much you can get away with changing synth sounds through processing, because no‑one but you knows what the source recording actually sounded like!

That said, while referencing the mix later, it was clear that the bass was losing too much level and body in the transition to mono — an important consideration if you're interested in broadcast. With this in mind, I further supplemented the sound with a mono distortion send effect, combining SimulAnalog's Ob PS1 and Rednef Twin with some ReaEQ, and panned this dead‑centre. This didn't make an vast difference to the sound in stereo, but provided real assistance with the bass balance in mono.

That said, while referencing the mix later, it was clear that the bass was losing too much level and body in the transition to mono — an important consideration if you're interested in broadcast. With this in mind, I further supplemented the sound with a mono distortion send effect, combining SimulAnalog's Ob PS1 and Rednef Twin with some ReaEQ, and panned this dead‑centre. This didn't make an vast difference to the sound in stereo, but provided real assistance with the bass balance in mono.

Building Up The Rest Of The Kit

The foundation of the track was now laid, upon which I could build the remainder of the drums. I'd decided that I wanted to make them brighter and more urgent‑sounding than Chris had chosen to do, as well as steering clear of the reverb effects that had clouded the original mix. Tonally, most of the brightening I wanted could be achieved by bussing all the drums to a single channel and then boosting with the URS Console Strip Pro plug‑in's Pultec EQ emulation at the top end: 6dB shelving boost at 6kHz, with a Q factor of 1.01, to be precise! Channel‑specific EQ boosts could then be kept fairly small for the six remaining drum samples (two snares and four hi‑hats). Transient Monster supplied a touch more attack for one of the snares, while SSL's freeware Listen Mic Compressor extended the sustain for an open hi‑hat.

Now to try to give a bit more attitude and movement by getting the dynamics of the instruments to interact. The most common way to do this is to apply a common compressor to them, such that the louder hits cause obvious gain‑pumping of the drum mix as a whole, an effect which also helps give an impression of loudness by broadly emulating how the ear reacts in response to loud signals. The pitfall of this approach to creating gain pumping is that you can easily compromise the sound of your kick and snare beats in the process, and given that this kick was so important, I figured I'd try an alternative parallel‑compression method as a first port of call.

Setting up a compressor as a send effect, and mixing the compressed signal back into the mix, I was able to apply Stillwell Audio's ridiculously fast The Rocket compressor in its 'All Buttons' mode to most of the drum parts, thereby creating an exaggerated pumping effect without interfering with main kick and snare hits (which were bypassing the compression). I could also sneak in some valve saturation from Wurr Audio's Tube Booster after the compressor, to thicken up the sustain of the snare and cymbal sounds, but again without any transients fracturing unduly in the process.

Setting up a compressor as a send effect, and mixing the compressed signal back into the mix, I was able to apply Stillwell Audio's ridiculously fast The Rocket compressor in its 'All Buttons' mode to most of the drum parts, thereby creating an exaggerated pumping effect without interfering with main kick and snare hits (which were bypassing the compression). I could also sneak in some valve saturation from Wurr Audio's Tube Booster after the compressor, to thicken up the sustain of the snare and cymbal sounds, but again without any transients fracturing unduly in the process.

The parallel processing added aggression and 'bounce' to the whole drum sound, and had the beneficial side‑effect of pulling up the internal ambience in the samples, giving more of a live feel without my having to resort to any reverb. As I sometimes do, I also added in a bit of background vinyl noise to the drums, which emphasised the room sound further, as well as binding the whole drum sound together.

Working With A Ducking Send

I was now pretty happy with the way the drums and bass were fitting together, but as I began building up the rest of the mix I felt that the kick drum could still pop out more. The big challenge here is keeping the kick present and clearly audible without having to fade it up too far in the mix balance, and there are various tricks that can make a difference. The one I went for was ducking parts of the mix in response to the kick drum, clearing away some of the sounds masking it, and therefore bringing it more up front without actually increasing its level.

You can achieve ducking effects in lots of ways in modern sequencers, probably the most common choice being to insert compressors on each of the tracks to be ducked before sending the kick‑drum signal to the side‑chain of each. However, I prefer a slightly different approach, which can be applied to multiple tracks without much routing. What I do is set up a gate plug‑in, keyed from the kick‑drum, in its own Reaper channel as a send effect, and then I invert the polarity of the effect channel. This means that anything I send to the gate will phase‑cancel itself whenever the kick hits. I can then configure how much to duck each track by adjusting its send level to the ducking track.

For fairly transparent drum‑triggered ducking, I'd normally use pretty fast attack and release times on the gate just to duck sounds during the drum's transient (I've gone into this in more detail in this month's Cubase column starting on page 172), but here I decided to enhance the drums' pumping effect by lengthening the release time to 185ms in the ReaGate plug‑in I had chosen. In the end I ducked the snare and hi‑hat parts fairly heavily, because it gave things a slight 'Firestarter' vibe, as if drums had been made up of separate kick and breakbeat samples. I did also duck a couple of the more sustained synth drone parts.

For fairly transparent drum‑triggered ducking, I'd normally use pretty fast attack and release times on the gate just to duck sounds during the drum's transient (I've gone into this in more detail in this month's Cubase column starting on page 172), but here I decided to enhance the drums' pumping effect by lengthening the release time to 185ms in the ReaGate plug‑in I had chosen. In the end I ducked the snare and hi‑hat parts fairly heavily, because it gave things a slight 'Firestarter' vibe, as if drums had been made up of separate kick and breakbeat samples. I did also duck a couple of the more sustained synth drone parts.

As the final stage of achieving the pumping sound you can hear on my remix, I also sent pretty much the whole mix through a bus compressor so that drum peaks would modulate the levels of all the other instruments to some extent. I kept the gain reduction fairly moderate, though, registering only about 4dB on peaks using a 4:1‑ratio emulated SSL E‑series channel compressor running in URS Console Strip Pro. Just to be sure I wasn't going to kill the kick transient, I fed a little of it direct to Reaper's outputs, bypassing the main buss compressor, keeping the punch intact even as the track level overall built up.

De‑essing The Drums?

For me, another real challenge of this mix was dealing with the vocal sibilance, especially as 's' sounds featured so heavily in the chorus sections. The raw recordings were already fairly sibilant, just by virtue of the specific mic and miking position used. Once I'd added some fairly heavy compression to keep the vocals in their place in the mix, though, the problem was further exaggerated. Typically this isn't too much of a problem, because a combination of a decent de‑esser and maybe some automation can cure most ills (again, this is a topic we've covered in more detail this month, on page 44). In this particular instance, I found that, even with two separate instances of Waves Renaissance De‑esser running on each part, no combination of processing I could come up with would stop the esses sounding abrasive without also giving the singer a thick lip!

The reason for this was that the frequency region that accounted for the harshness of the sibilance (roughly 8‑10kHz) was also an important frequency range for the drum parts, so there was already a lot going on up there. This meant that sibilants that sounded fine in solo felt overbearing when their HF energy combined with that of the drum parts. Given that there was only so far I could process the vocals before they lisped, there was therefore no alternative but to try to remove some of the highs from the drums. I was loath to do this with simple static EQ, as I liked their edgy sound.

Ideally, I'd have liked to be able to insert de‑essers across the drum tracks, triggering them from the vocals, but I've yet to come across a de‑esser with side‑chain access! I've used multi‑band compressors for de‑essing in the past, so my next thought was that Reaper's ReaXcomp multi‑band compressor might work instead — but that also had no external side‑chain. So instead, I chose to go back to the traditional implementation of de‑essing using a compressor. The way you do this is by using EQ in the compressor's side‑chain to isolate the sibilant frequency region, thus encouraging the compression only to kick in when sibilants come along.

Ideally, I'd have liked to be able to insert de‑essers across the drum tracks, triggering them from the vocals, but I've yet to come across a de‑esser with side‑chain access! I've used multi‑band compressors for de‑essing in the past, so my next thought was that Reaper's ReaXcomp multi‑band compressor might work instead — but that also had no external side‑chain. So instead, I chose to go back to the traditional implementation of de‑essing using a compressor. The way you do this is by using EQ in the compressor's side‑chain to isolate the sibilant frequency region, thus encouraging the compression only to kick in when sibilants come along.

In this case, that meant that I had to insert compressors on the high‑frequency drum parts and then feed an EQ'd version of the vocal to their side‑chains. While this wasn't the easiest thing to set up, it did make the difference I was hoping it would, so was worth the effort! I set the compression fairly fast, to try to avoid the release time, in particular, giving away what I was doing, and then adjusted the threshold and ratio controls of each compressor until I could hear the sibilance smoothing out. With hindsight, I thought up a couple of more elegant ways to implement this processing in Reaper, but the approach I actually used worked just fine and can be applied within any sequencer that offers side‑chain access to its compressors.

Refining Arrangement & Programming

Beyond dealing with the combination of bass, drums, and vocals, the heaviest lifting on this mix was dealing with various arrangement issues. My main worry as a listener was that there was too much repetition going on, in general, and when parts came in they tended to repeat unchanged for long periods. The first down side of this is that your ear starts to ignore any musical part the more it repeats, which waters down that part's emotional impact. You also have to consider that any such repeating parts will also be crowding out any new parts that arrive, masking many of their qualities and making them less arresting too.

Much of what I did in this vein was simply reducing the amount of repetition. With the drum parts, this was merely a case of chopping out the odd beat (for example, at 1:49 in the remix) or rearranging the beat slightly to create a slight fill (as at 2:57 and 3:49). The sub‑bass track I'd added was a good candidate for some thinning out, so I simplified that during the first half of the first verse and at a couple of other points, to expand and contract the low‑end range. Another part I muted out during the first verse was the high electric guitar line (with its accompanying step‑filter effect) that appears in the second half of each verse in the original mix. The basic principle behind changes like these is to give each new section some new twist, even if much of what's happening is a recap of something that's gone before.

A few other synth and electric guitar parts were just too thick and sustained for the track, such that they blotted out lots of more interesting stuff if they were faded up far enough to be audible. In these cases, I took the scissors tool to them and perforated the audio regions in a rhythmic manner, trying to leave in only those sections of the part which seemed worth hearing — the slightly Middle Eastern‑sounding riff first heard at 1:18 being one such notable segment.

I quickly concluded that these usual tricks were unlikely to elevate the arrangement dynamics to the kind of level I was looking for, so once I'd got a fairly complete mix of the existing parts, I began to add in a few extras to fill in the gaps. One quick fix was to chop out a few little audio fragments, particularly some vocal phrases in the break‑downs, and go mad with the special effects to provide a bit of ear‑candy. For this kind of sound design, there aren't any useful guidelines I can offer other than to keep pushing buttons until you catch yourself both laughing and swearing at the same time!

I like to use these kinds of occasion as a chance to experiment with weird and wonderful plug‑ins that I don't otherwise use much. As usual, I first made a bee‑line for Jack Dark's Darkware plug‑ins, but (again as per usual) these provoked either mirth or profanity, but not both, so I headed elsewhere — I'm determined to find a use for them one of these days! Next stop was Tweakbench's range of step‑sequenced effects, but they didn't give me any of the extra sustain that I felt would be useful. Only when I got to Waves Enigma did I strike gold for the first time, ending up with the trippy modulation/reverb effects that appear on the vocal at 1:35 and on the electric guitar chord at 2:42. I further mangled the latter with Schwa's new Tin Man resonator plug‑in, just blindly twisting controls until something cool happened. (While writing this article I thought I should quickly check out Tin Man's two‑page PDF manual to find out what I'd done, and it's well worth the read — if for no other reason than that I averaged about six good laughs a page!)

Demelza, who collaborates remotely with Chris Durban.The long vocal feedback delay effects you can hear at 2:45 and 3:34 were achieved using The Interruptor's freeware Echomania delay plug‑in, which I didn't bother to try to understand, surfing the presets and fiddling with the Master Feedback control until I got something that sounded suitably crusty. For the second of these feedback delays I also popped in an instance of Tin Brooke Tales funky little freeware Tape Stop plug‑in to create the pitch‑dive that leads into the re‑entry of the drums. If you've not come across this plug‑in before, it's been designed to simulate the sound of you stopping and/or starting playback on a tape‑machine or turntable. It's not exactly something you use on every mix, but I thought it worked pretty well here once I'd spent a bit of time with its speed parameters to get the timing of the pitch‑slide in a good place.

Demelza, who collaborates remotely with Chris Durban.The long vocal feedback delay effects you can hear at 2:45 and 3:34 were achieved using The Interruptor's freeware Echomania delay plug‑in, which I didn't bother to try to understand, surfing the presets and fiddling with the Master Feedback control until I got something that sounded suitably crusty. For the second of these feedback delays I also popped in an instance of Tin Brooke Tales funky little freeware Tape Stop plug‑in to create the pitch‑dive that leads into the re‑entry of the drums. If you've not come across this plug‑in before, it's been designed to simulate the sound of you stopping and/or starting playback on a tape‑machine or turntable. It's not exactly something you use on every mix, but I thought it worked pretty well here once I'd spent a bit of time with its speed parameters to get the timing of the pitch‑slide in a good place.

Even with a few more special effects in place, I still felt a bit underwhelmed, and headed to my sample library for inspiration. Some metal stress noises from Best Service's veteran XFX sound‑effect library helped to provide background interest at various points, as well as setting the mood during the drums introduction. Soundlabel's Xtreme Whooshes (what a name!) supplied a couple of new transition effects in addition to the one that Chris had used, and I also couldn't resist a few bits and pieces from Heavyocity's Evolve Kontakt Instrument, a current favourite of mine: a couple of rhythmic tonal loops which added some new texture to the general groove, and a high metallic lead line, all of which can be heard during the third verse (beginning at 2:58).

Ninja Rhythm Processing

Such is the importance of kick and bass to dance music that many unusual and specialised mixing techniques have now been developed by producers wanting to out‑gun each other in this department. If you're new to these kinds of 'ninja' side‑chaining and bus‑processing techniques, it can be disheartening trying to get your mixes to compete with those from the big names, so I hope that I've been able to shed some light on how they can work for you in practice. At the end of the day, though, no sonic perfection is going to make up for a lack of interest in the arrangement, so it can often pay dividends to revisit and rework this aspect of the production throughout the mixing stage.

Rescued This Month

Chris Durban has been writing and producing music at his London home for the last three years. He's currently in the middle of a studio project with Dartmoor‑based Demelza Jennings, formerly lead singer of drum‑and‑bass band Obedientbone. They work for the most part remotely, with Chris starting work on a song in Sonar 6 using a variety of virtual instruments. In the case of 'Celebrate', these included Spectrasonics' Stylus RMX, Native Instruments' Massive, and a handful of Cakewalk soft synths. Chris then sends work in progress to Demelza, who overdubs vocal and guitar parts at a local studio, before Chris further develops the song and proceeds to the mixdown.

Remix Reactions

Chris: "Whoa! How did you do that?! Not only does it sound a whole lot cleaner but the arrangement, from start to finish, works much better through some neat production techniques. The whole track is more cohesive, and the kick and drums are much punchier and tighter. The original drums were a bit loose, and as a result they lacked that bit of killer edge. The bass line is more prominent, while some of the synths that were completely lost in the original mix now stand out boldly. For me, though, it's the improvement in the dynamic of the track that has impressed me most. The careful attention to the role of different sounds in different parts of the track has created a slicker sound.”

Demelza: "I love it! Nothing has really been taken out of the track — if anything it feels like there are more parts — but the whole mix feels less cluttered, even in the busy parts. Also, the breaks have more impact and the high‑mid frequency clashes that were apparent in the original mix have been resolved. There is less bottom end, and although I might have liked some more, the track does feel more balanced as a result.”

Before & After

To accompany this article, we've placed some before and after audio files in both WAV and MP3 format on ourweb site, so you can hear for yourself the differences made by Mike to this mix. Go to /sos/may09/articles/mixrescueaudio.htm for details.