With Sara Bareilles' massive worldwide hit 'Love Song', producer Eric Rosse had to strike a delicate balance between preserving the artist's integrity and achieving mass appeal.

Eric Rosse at his Squawkbox Studios, where 'Love Song' was mixed.Is it possible to write a hit song to order? In the case of Sara Bareilles' recent hit 'Love Song', it would seem that it is — when the song in question is a scathing response to the demand for a hit. 'I'm not gonna write you a love song,' runs the chorus refrain, 'cause you asked for it, 'cause you need one, 'cause you tell me it's make or break.' Replace 'love' with 'hit', and the song reveals itself as a not-very-thinly veiled dressing down of her record company.

Eric Rosse at his Squawkbox Studios, where 'Love Song' was mixed.Is it possible to write a hit song to order? In the case of Sara Bareilles' recent hit 'Love Song', it would seem that it is — when the song in question is a scathing response to the demand for a hit. 'I'm not gonna write you a love song,' runs the chorus refrain, 'cause you asked for it, 'cause you need one, 'cause you tell me it's make or break.' Replace 'love' with 'hit', and the song reveals itself as a not-very-thinly veiled dressing down of her record company.

'Love Song' has gone multi-platinum and sold well over a million copies worldwide: not bad for the debut single of a hitherto-unknown 28-year old musician from California. Bareilles' path to the top has been smoothed by producer, songwriter, engineer, mixer, arranger and keyboardist Eric Ivan Rosse, who first became known for helping shoot Tori Amos to fame in the early '90s. Rosse has since gone on to work with other female singer-songwriters such as Lisa Marie Presley, Anna Nalick, Kristy Thirsk and Nerina Pallot, and has also had success with the likes of Chris Isaak, Gus, and the band Critters Buggin'. He's often found developing unknown artists, as was the case with Sara Bareilles, with whom he began working in July 2005.

"The time scale of the process was quite lengthy," explains Rosse. "When Sara and I got together we started working on a couple of things, and I helped her develop her direction a little bit more. We talked through stories of songs, arrangement ideas, song structures, things like that. We continued to get together twice a week for five months, while I was pointing out directions to her in the way she could write songs. She came up with a lot of material, and we would demo stuff, just piano/vocal, and send it off to Pete Giberga [the A&R manager], who was getting excited about the project. Sara wrote 'Love Song' halfway through this period. She knew that there was a certain amount of pressure to write a song that was going to be a single. I think this issue was a struggle for Sara, because she really is an artist, and feels that just writing music from the heart should be enough. Pete is very artist-friendly, but he's also aware that if the promotion people and the president and others in the company don't feel they have a song to promote the album, nothing is going to happen."

In her on-line biog, Bareilles notes about working with Rosse, "I'm not proud to say it, but I feel like in many ways I walked in with my dukes up." Rosse quietly acknowledges this, and explains, "Yes, she did need a bit of convincing. But rather than trying to get her to do something she didn't want to do, I felt that it was my job to try to get the best of all possible worlds by supporting her in doing something that she wanted to do, and that would also get the record company excited. And so she came up with 'Love Song'. It is a matter of walking that balance, which I do a lot in my work, primarily of supporting the artist in doing what he or she wants to do, but also making sure the record company feels that it gets what it needs."

The Quest For Pianos

"Sara came in one day with the initial musical idea which included the phrase 'I'm not going to write you a love song,' and the rest was sort of la-la-la. Structurally it was a bit different from the final version: there might not have been a bridge and I can't quite remember how she did the pre-chorus. But there definitely was a basic structure to the song, with most of the music, the main hook line, and several verse ideas. We discussed where the song could go, thematically and structurally, and she went away and came back with more or less the finished song. I think that for Sara the idea of a love song was synonymous with a commercial hit, so she was taking poetic license with the term.

"Sara came in one day with the initial musical idea which included the phrase 'I'm not going to write you a love song,' and the rest was sort of la-la-la. Structurally it was a bit different from the final version: there might not have been a bridge and I can't quite remember how she did the pre-chorus. But there definitely was a basic structure to the song, with most of the music, the main hook line, and several verse ideas. We discussed where the song could go, thematically and structurally, and she went away and came back with more or less the finished song. I think that for Sara the idea of a love song was synonymous with a commercial hit, so she was taking poetic license with the term.

"It was quite obvious from the beginning that there was going to be a lot of focus on 'Love Song' so a lot of work went into it. We recorded three different versions of the song, though the vocal remained the same throughout each incarnation, and we built the track around that. I had recorded demos of all the songs for the album at my studio, recording her vocals with my vintage Neumann U87, which I ran through an API 3124M mic pre or my Audio Upgrades Class A custom-built stereo mic pre, a GML 8200 EQ, and a Teletronix LA2A compressor, straight into Pro Tools. We did a bunch of other vocal takes later on, but the original take was for the most part the best. We took only a few bits and piece from later takes.

"The first step of recording the backing tracks for the album was that Sara and I drove around LA for a day, trying out pianos for her in four or five different studios. We felt that a Yamaha seven-foot grand at NRG studios suited her music the best, so we did the basic tracks — piano, drums and bass — at NRG. The remainder, Yamaha CP80 electric piano, Mellotron, guitars, backing vocals, were overdubbed at my own studio, Squawkbox. Howard Christopher Willing engineered the NRG sessions, and we recorded the piano with a pair of B&K 4011 mics close on the strings, a pair of Royer ribbon mics in a more classical configuration standing further away, and a Telefunken 251 in between the Royers, standing back a further six inches from them.

The first half of the Pro Tools Mix Window for 'Love Song'. From left: drums, piano, CP80, Mellotron, acoustic and electric guitars."For most of the songs on the album we had excellent guide vocal/piano recordings, and the other instruments were overdubbed to those. They set the tone for what the songs should be. Sara also cut two songs live with the band. The overdubs for 'Love Song' initially didn't sit right with the main vocal recording, which we liked, so we had to re-assess our approach. The issue was mainly one of feel. A four-to-the-floor feel can easily sound heavy and laboured, so I wanted to make sure that the rhythm had enough movement. It had to drive the song forward, and not feel plodding, but also not feel so happy or poppy that it would make the song sound silly. We used two drummers on the song, and the final drum take took place at Sunset Sound. The piano was tracked twice, because it had to match the new feel of that last drum overdub. We also did a number of different approaches with the guitars, and there's a very subtle drum loop, programmed by Jake Davies, that you sort of hear rather than feel, but that helped drive the song forward."

The first half of the Pro Tools Mix Window for 'Love Song'. From left: drums, piano, CP80, Mellotron, acoustic and electric guitars."For most of the songs on the album we had excellent guide vocal/piano recordings, and the other instruments were overdubbed to those. They set the tone for what the songs should be. Sara also cut two songs live with the band. The overdubs for 'Love Song' initially didn't sit right with the main vocal recording, which we liked, so we had to re-assess our approach. The issue was mainly one of feel. A four-to-the-floor feel can easily sound heavy and laboured, so I wanted to make sure that the rhythm had enough movement. It had to drive the song forward, and not feel plodding, but also not feel so happy or poppy that it would make the song sound silly. We used two drummers on the song, and the final drum take took place at Sunset Sound. The piano was tracked twice, because it had to match the new feel of that last drum overdub. We also did a number of different approaches with the guitars, and there's a very subtle drum loop, programmed by Jake Davies, that you sort of hear rather than feel, but that helped drive the song forward."

'Love Song'

Written by Sara Bareilles

Produced by Eric Ivan Rosse

The second half of the Mix Window is devoted to vocals, plus the busses used to return the mix from Rosse's Dangerous 2-Bus summing mixer.Eric Rosse: "I'm doing more and more mixing, and mixing tracks that I haven't recorded accounts for about 50 percent of my work these days. When I approach a mix of a song that I have also recorded and produced, I deliberately put in my mixer brain, which is different from a producer brain. For me it's important to distinguish between the two. As a producer, you can get very attached to things that you created and that you may have worked very hard on, sometimes for many months. If possible, I like to step away from a project for at least a week before mixing, and then get back to it with fresh ears and try to mix it as if I'm hearing it for the first time. You hear things differently as a mixer, and the creative challenge is not to hinder your freedom to create something that you might not have thought of before.

The second half of the Mix Window is devoted to vocals, plus the busses used to return the mix from Rosse's Dangerous 2-Bus summing mixer.Eric Rosse: "I'm doing more and more mixing, and mixing tracks that I haven't recorded accounts for about 50 percent of my work these days. When I approach a mix of a song that I have also recorded and produced, I deliberately put in my mixer brain, which is different from a producer brain. For me it's important to distinguish between the two. As a producer, you can get very attached to things that you created and that you may have worked very hard on, sometimes for many months. If possible, I like to step away from a project for at least a week before mixing, and then get back to it with fresh ears and try to mix it as if I'm hearing it for the first time. You hear things differently as a mixer, and the creative challenge is not to hinder your freedom to create something that you might not have thought of before.

"Since I knew 'Love Song' would get a lot of attention from the label, I wanted to make the song as driving and aggressive as I could, and feature Sara's voice as much as possible, squeezing every ounce of energy out of it. By the time it came to mixing, the issues we had during tracking were entirely resolved, and I was only looking at minor things, like how many backing vocals to use, and how much of a vocal double there should be. Sara associates lead vocal doubling with slick–sounding pop music, so we had to come to various levels of compromises on that. But in general the heavy lifting had been done on this song, and it was just a matter of making it sound and feel really good.

"When I start a mix, I throw up all the faders and move them around to get a rough sense of the balance and to hear what's there. I'll then prep the mix by splitting things out into channels towards my 32-channel Dangerous 2-Bus [summing mixer], making sure I have as much separation as possible between the different channels, and picking the outboard effects I want to use and patching them in. I then go back to the mix, and usually I mute everything except the drums and vocal. I'll get the drums right for the song, and I also try to get the vocals sound as good as possible. I'll then build the rest of the track around the vocals and the drums, adding bass and other primary instruments, in the case of 'Love Song' the bass and the piano, making sure I get a driving rhythm. I'll then add other instruments as textures and colours, in this case guitars, electric piano, Mellotron, and backing vocals. I never get a track sounding great and then try to fit in the vocals with that, because you'll almost certainly end up drowning the singer."

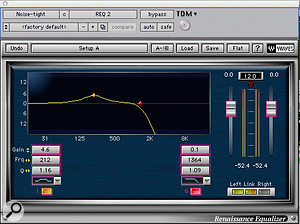

Digidesign's Impact compressor was used to treat the drum overheads, while a room mic was heavily EQ'd with Waves' Renaissance EQ.Drums: Focusrite D2 EQ, Digirack Compressor/limiter, API 550A EQ, Roland SRC2000 reverb, Waves Renaissance Vox and Renaissance EQ, Digidesign Impact.

Digidesign's Impact compressor was used to treat the drum overheads, while a room mic was heavily EQ'd with Waves' Renaissance EQ.Drums: Focusrite D2 EQ, Digirack Compressor/limiter, API 550A EQ, Roland SRC2000 reverb, Waves Renaissance Vox and Renaissance EQ, Digidesign Impact.

"'Love Song' has 12 drum tracks, including five room tracks, plus a room aux. To the right of the aux [in the Pro Tools Mix Window] are three bass channels, followed by six tracks of cymbals, and a track called 'noise', which is the subliminal programmed percussion loop. The cymbals give a bit of splash at the beginnings of choruses and things like that. Sometimes I'll take a cymbal crash from another part of the song or another drum take, and fly it in for a particular section. I think I also did this in this case. It's quite an elaborate drum recording, which allowed me to have lots of options for changing the sound and the feel of the drums in different songs. I didn't always use all these drum tracks — in some songs I may only have used six drum tracks, and in the 'Love Song' Edit Window, you can see that I greyed out one whole drum track, as well as sections of other drum tracks.

"The drums were recorded really well, so I didn't have to do very much during mixing, other than balancing. The EQ and effects were subtle and more surgical, like removing a frequency that had a little too much boom in it, or adding something. I'm doing this on the kick drum, for instance, on which I rolled off a little bit of low-mid and added a little bit of top end with the Focusrite D2 plug-in. The snare has a tiny bit of plug-in compression from the Digirack compressor, which was a carry-over from the overdub process. It sounded good, so I left it. Generally speaking, I don't use many plug–ins during recording, but working with Pro Tools is an additive process and you start to approach something that feels like a mix as you build a song. It allows you to do that because of the recall. So you try an EQ plug-in here or a compressor plug-in there. During mixing I keep these plug-ins if I like them, but I may change the settings. In other cases I may remove a plug-in and do something similar with an outboard unit.

The complete Pro Tools Session for 'Love Song'."The kick and the snare were assigned to outputs 3/4 in Pro Tools, which I had patched into two of my 10 API 550A EQs, and then routed to inputs 3/4 on the Dangerous 2-Bus mixer. I boost some low and high on the kick and some high and mids on the snare. I also used the APIs on the overheads (a tiny 10k boost), the mono overhead (low and mid boost) and the Shure Room 1. The latter had an extreme high-end roll off, a boost in the low mid, and a small boost in the low end. The Shure Room mic was heavily compressed when it was recorded, and it added energy, texture, and personality to the drum sound. I love my APIs. They are from the early '70s. They've been reconditioned by Brent Averill and they sound really clean. I tend to use the APIs for their sound, rather than surgical precision, but in general it's not a matter of using plug–ins for one thing and outboard for the other. There are some plug-ins that sound really fantastic. I mix and match.

The complete Pro Tools Session for 'Love Song'."The kick and the snare were assigned to outputs 3/4 in Pro Tools, which I had patched into two of my 10 API 550A EQs, and then routed to inputs 3/4 on the Dangerous 2-Bus mixer. I boost some low and high on the kick and some high and mids on the snare. I also used the APIs on the overheads (a tiny 10k boost), the mono overhead (low and mid boost) and the Shure Room 1. The latter had an extreme high-end roll off, a boost in the low mid, and a small boost in the low end. The Shure Room mic was heavily compressed when it was recorded, and it added energy, texture, and personality to the drum sound. I love my APIs. They are from the early '70s. They've been reconditioned by Brent Averill and they sound really clean. I tend to use the APIs for their sound, rather than surgical precision, but in general it's not a matter of using plug–ins for one thing and outboard for the other. There are some plug-ins that sound really fantastic. I mix and match.

"I used the Waves Renaissance EQs on the two tom tracks, and also on the room mics, doing subtle levels of low-end roll-off, and adding mid-range or high end. The room mics had quite a lot of low end, and I needed to control that. The REQ4 on the aux and the hi-hat and REQ6 on the Shure Room 1 mic are also the Waves Renaissance EQ, just with more bands. There's quite a radical curve on the REQ6, with the mid-range frequencies almost completely rolled out. I used the Digidesign Impact on the overhead tracks. It sort of emulates the SSL compressor, and I like it. It's just doing a subtle amount of compression. Finally, the snare has a little bit of reverb from my very old Roland SRV2000. It's from the '80s and I still use it because it has a few favourite settings.

A percussion loop was gated and EQed to sit beneath the live drums."There are three plug-ins on the Noise track, which is the programmed percussion loop: a Digidesign noise gate, to tidy up the spaces in between the hits in the loop, a Renaissance Vox compressor, which is designed for use on vocals, and which I set here with a very moderate amount of compression, and the Renaissance EQ, which has a high-frequency roll-off at about 12k. I didn't want the loop to be too bright. I wanted it to be felt, rather than actually heard."

A percussion loop was gated and EQed to sit beneath the live drums."There are three plug-ins on the Noise track, which is the programmed percussion loop: a Digidesign noise gate, to tidy up the spaces in between the hits in the loop, a Renaissance Vox compressor, which is designed for use on vocals, and which I set here with a very moderate amount of compression, and the Renaissance EQ, which has a high-frequency roll-off at about 12k. I didn't want the loop to be too bright. I wanted it to be felt, rather than actually heard."

All five piano mics were routed to a single bus, where EQ and compression were applied.Piano: Digirack EQ III, Focusrite D2 EQ, Digirack Compressor, Waves Renaissance EQ, Bomb Factory Fairchild 660.

All five piano mics were routed to a single bus, where EQ and compression were applied.Piano: Digirack EQ III, Focusrite D2 EQ, Digirack Compressor, Waves Renaissance EQ, Bomb Factory Fairchild 660.

"With a B&K stereo pair, a Royer stereo pair and a Telefunken 251 mono mic, it was an intricate way of recording a piano. Some of it was an experiment, but those microphones all have different qualities to them, so recording them all gave me a lot of control over how much room sound I wanted to have in the piano recording. Each microphone has a different EQ curve, and by mixing them a certain way, I could also have the effect of EQing the piano, without actually using EQ. I did use plug-in EQ, though, at slightly different frequencies for each mic. I used the seven-band Digirack EQ on the B&K pair, adding around 9k and 100Hz, and the Focusrite D2 on the Royers, with a boost at 11.5k. For the 251 I just used a very subtle amount of Digirack compression. All five mic tracks are bussed via buses 5/6 to an aux channel, on which I have a Renaissance EQ doing a slow roll-off at 70Hz down to 30Hz, to clean up any rumble, a lot of which came from the 251.

"I also used the Fairchild 660 to compress the piano quite a bit, because she is chugging away throughout the song, and I wanted the piano to be the rhythmic driving force. The compressor is set to make the amplitude of the attack quite sharp and the tail end of the hits get compressed a bit more, so you get quite an impact out of each hit on the piano. The compressor settings are slow attack, to let the initial spike through, then as a quick release as possible, and about 4-5dB of compression. I used the Fairchild purely to get more punch and not to sweeten up the sound, and that plug-in does that very well. I didn't use any outboard on the piano, it was all in the box."

- Keyboards: Digidesign Long Delay, Ensoniq DP4, Marshall amplifier.

"Sara played all keyboards, including my Yamaha CP80, which you can hear doing a five-note melody in the re-intro and the outro. I recorded the CP80 through a 50W Marshall electric guitar amplifier, miking the amp with a Microtech Gefell and a Shure SM57. I love the CP80, because it reacts really well to that. You can really distort it, and it sounds really cool. The Digidesign delay simply creates a long stereo delay, 243ms on the left and 488ms on the right, which is panning from left to right, to get a nice stereo effect. The original sound would be in the centre, and the delays would be left and right, giving a spacious effect. I was playing with the idea of distorting the piano more with the Amplitube, but I did not use it.

"The Mellotron plays a background part in the B-section of the song, some people call it the pre-chorus. The 'L' and 'H' channels, low and high, are muted in the actual Edit Window. It must have been a last-minute decision not to use them. The Mellotron 'B' section and 'B' section double are used, and they have the same long Digidesign delay as the CP80. I also gave the Mellotron a little bit of reverb from my Ensoniq DP4, which most people look at as some strange relic from another time, which it sort of it is. But I have some settings in it that I created and that I really like." One of many guitar tracks was EQ'd to take out the low end and boost at 6kHz.

One of many guitar tracks was EQ'd to take out the low end and boost at 6kHz.

"There are quite a few guitar tracks: seven acoustic and 11 electric! Most tracks only play for limited periods of time, and the guitars are also layered for texture, so it's not as much as it seems. 'AcGtrBrglp' is a pulsating guitar that has a low-end roll–off and 4k and 9k added, using the REQ4, to get it to cut through. It also has a very subtle amount of Digirack compression. 'Ac Gtr' and 'Ac Gtr-Dist' are the main acoustic guitars. I reamped them to add distortion and then recorded them back into Pro Tools — they come up again on the two tracks to the right — and I then phase-aligned them and mixed them in behind the original acoustic guitars. That gave the acoustic guitars a little bit more edge. I also used two API 550A EQs on the main acoustics, adding a little bit of high end, around 9k or 10k, and perhaps adjusting the mid-range, so that they would fit into the track.

"The electric guitars have completely different sounds and different settings in different sections, and are mainly there for colour. 'Brg Elect' has a small amount of Renaissance compression on it, slow attack, slow release, 3:1 ratio, and a little bit of stereo Digirack delay that was sent through buses 31/32. That was my main guitar delay, and I also ran the CP80 through that. The 'Reintro' gtr only occurs for two short moments in the second verse, and has Digirack compression: slow attack, fast release and a 4:1 ratio. 'V2 Gtr-cmp' is a bluesy guitar with a Fairchild 660 with fast release and about 3-4 dB gain reduction.

"'Gtr-PnoDbl' doubles the sound of the CP80 electric piano and I added some Amp Farm distortion to match the piano sound, plus some subtle Digirack compression, fast attack, medium release, 3:1 ratio. The three chorus guitars are all playing the same thing, and have 5k added by two 550As. The 'Ch Gtr' also has a slightly more radical Focusrite D2 EQ with an extreme low-end roll-off at 200Hz, and a boost at 6k, just to make it bite and cut through, plus a very small amount of Digirack compression, with a very fast attack and a slow release. So I'm trying to get rid of the punch on this one. It was also being sent via bus 29 to the Ensoniq DP4 multi-effects, set to a fairly short, medium-sized room, with a short delay on the reverb. The D2 on the 'Stu' guitar track is set to a sharp low-end roll-off at 140Hz, a boost at 1k and a boost at 6k. Elsewhere I also have a track called 'DLY-L-R', which is an aux track with a long Digirack stereo delay, and through which I ran a bunch of guitars. The delay has a shorter setting on the left and a longer setting on the right, to give it a sort of left and right effect, a bit like with the piano. There is a little bit of Renaissance EQ on it, just adding at 11k."

Digidesign's Pitch plug-in was used to create a doubling effect on a send from the lead vocal, which was then EQ'd to keep it in the background.

Digidesign's Pitch plug-in was used to create a doubling effect on a send from the lead vocal, which was then EQ'd to keep it in the background.

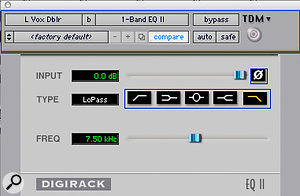

"The 'L Vox Comp' track is the main lead vocal, and it is sent through a GML 8200 outboard EQ, then through a Distressor for some compression, and then returns through Pro Tools input 5, which is my aux, and is re-output through Pro Tools output 22, from where it went into my Dangerous 2-Bus. The aux is moved forward in time to compensate for going into analogue and the two outboard effects being used outside Pro Tools. The Digidesign delay on the aux was a 16th-note delay, in mono, and the track also has a high–frequency roll-off, rolling off pretty much everything above 900Hz. I did this to mimic the effect of an old tape delay.

"'LVox Dblr' is an auxiliary return that has the Digirack Pitch plug-in on it and acts like an outboard harmoniser. I am sending a little bit of the lead vocal through it in the choruses. I have 15 cents worth of harmonisation on that and a 26ms delay, and also a one-band EQ for a little bit of high-end roll-off at 8k. Like the aux, I wanted it to be a little bit warmer-sounding than the lead vocal, so that it could be tucked underneath. 'xVoxDbl' is a lead vocal that Sara sung again, and it also was only used in the choruses. I added some short, small–room DP4 reverb to it. The 'Amc77' is a plug-in called Purple Audio Limiting Amplifier, which is supposed to mimic the sound of an 1176 compressor. The Focusrite D2 is set to a low-end roll-off at about 200Hz and a slight boost at 12k. I also ran the lead vocal double through a Sansamp distortion pedal and then re-recorded it, and that comes up as 'VoxDbl-Dst'. I used a small amount of that in conjunction with the double vocal to add some more texture."

- Backing vocals: Waves Renaissance EQ, Purple Audio Limiting Amplifier, Focusrite D2, Digirack Compressor.

"The chorus harmonies are all basically doing the same thing, and there are several layers. They are bussed to an auxiliary track, 'ChHarmAux', on which there's a bit of Renaissance EQ, with a low-end roll-off at 100Hz and a boost at 11k, and also the Purple Audio plug-in, with fast attack, fast release. The next set of BVs are bussed through 'BV Aux' and they go through similar effects, but instead I am using a Focusrite D2 EQ, adding 10k and rolling off at 500Hz, to create a mid–rangey–sounding vocal. 'BVhrmchrc' just has a Digirack Compressor, set for minimal compression at a 3:1 ratio. To the right of the 'BV Aux' is 'Bv-Ld', which is an ad lib track, where she sings a background line that is almost like a lead, and it has a Renaissance Compressor and a D2 with a low-end roll–off."

The Final Touches

"All the outputs from outboard gear come back through the 'FX Submix' track. Sometimes I also integrate various pedals, and everything runs through a submixer and back into Pro Tools via bus 3/4, so they can be integrated in the mix and automated if necessary. 'Mix Bus' is the return channel from the Dangerous 2-Bus mixer, which allows me to automate the 2-Bus. That gets routed to the actual mix channel, which is immediately to the right of it. It has a Waves PAZ analyser on it. I greyed it out, but I do remember using it. It allows you to analyse the frequency spectrum and phase, so you can see if there are low-end artifacts that you are not aware of while you are mixing, and double-check left and right balances and your phase and so on."

Squawkbox Studios

Located in the basement of his home in Silverlake, Los Angeles, Eric Rosse has his own state-of-the-art facility, designed to do everything from orchestral scoring for visuals to recording and mixing albums. A live room can accommodate drums, and the main recording equipment is a Pro Tools HD system with Focusrite Control 24 controller, ATR80 24-track tape recorder, Yamaha NS10 and ProAc Studio 100 monitors. Rosse is a big advocate of mixing through an external summing mixer, in this case a Dangerous 2-Bus: "The Dangerous 2-Bus is a glorified desk in a box. I really really like this particular unit, because I get the benefit of splitting out individual outputs of Pro Tools. There are a lot of reasons technically why people say that it should not matter whether one mixes in Pro Tools or analogue, but for me, there is a feeling and a punchiness that I believe I get out of the Dangerous. There tends to be a lot more headroom. Also, it allows a nice way to integrate my analogue outboard gear, which is still important for what I do."

The Control 24, meanwhile, "is basically a glorified mouse! But it's great to have faders, especially for mixing; I like to be able to put my hands on something and move faders around. There is a performance element that you can't get just by moving one fader at a time. The Control 24 does have a lot of additional functionality, but for tracking I like to use my dedicated mic pres."