The first step was to capture guide tracks, with Steve singing along to his acoustic guitar.

The first step was to capture guide tracks, with Steve singing along to his acoustic guitar.

Our engineer shows that there’s nothing wrong with living-room recordings if you approach them in the right way.

As a producer and studio owner, I’ve noticed a shift in the way many people seem to want to record in the last year or two: more and more artists are putting together projects outside of traditional studio setups before seeking the input of an engineer. Although affordable, good-quality recording gear has been available for several years now, many people resorted to this approach at least partly out of necessity, of course, with recording budgets shrinking all the time, but increasingly it seems to be the approach of choice. Whatever the reason, we professional engineers and producers are having to adapt to and embrace what, for many of us, is a different and more creatively collaborative way of working.

This month’s Session Notes is a case in point. I’ll describe the process behind the production and mixing of a track from the album House Music by Steven James Adams. This project is Steve’s first attempt to put an album together without a settled band to support him, and it was originally intended to be a stripped-back affair, with Steve keen to record the majority of the record in the front room of his house in London. As we worked on the initial demos, though, it quickly became clear that many of the tracks on the album were suitable for ‘filling out’ with extra instrumentation, and Steve decided to invite several guest musicians to contribute. Much of the work on these sessions centred on managing these guest contributions both in person, by recording them in Steve’s house, and by incorporating remote contributions by file transfer — an increasingly common approach, which presents its own unique challenges.

In The Beginning

To learn anything from this project, you’ll need to understand more about the general approach Steve and I adopted; I’m sure it will be familiar at least in part to quite a few SOS readers. Steve has both a full-time job and a young family, and rather than use precious holiday time booking a block of time, he made the decision to work on the album over a number of months, spending blocks of one or two days on it at a time. I would make the short drive from Cambridge to North London, taking my small mobile recording setup with me, and we’d get some things recorded, do a bit of listening together, and then go our separate ways. The project would then develop, with the aid of emails and the odd phone call.

Although we ended up keeping the guide guitar for much of the song, the track was filled out with additional acoustic and electric guitars.The starting point for the track I’m writing about here — and for the whole album, actually — was Steve singing along with his acoustic guitar. Working to a click track, which Steve is very comfortable with, I recorded the acoustic guitar and the vocals at the same time, just to get an initial version of the track down quickly. At this point, I didn’t intend this for use in the final record, but rather to capture a useful reference point that Steve and I could use as we considered the song’s evolving arrangement. However, experience has taught me to respect guide tracks as far as possible, so although I worked fast, I made sure I captured the performance fairly well, using a Shure SM7B dynamic mic on the vocals, and an AKG C414 large-diaphragm condenser to capture the guitar.

Although we ended up keeping the guide guitar for much of the song, the track was filled out with additional acoustic and electric guitars.The starting point for the track I’m writing about here — and for the whole album, actually — was Steve singing along with his acoustic guitar. Working to a click track, which Steve is very comfortable with, I recorded the acoustic guitar and the vocals at the same time, just to get an initial version of the track down quickly. At this point, I didn’t intend this for use in the final record, but rather to capture a useful reference point that Steve and I could use as we considered the song’s evolving arrangement. However, experience has taught me to respect guide tracks as far as possible, so although I worked fast, I made sure I captured the performance fairly well, using a Shure SM7B dynamic mic on the vocals, and an AKG C414 large-diaphragm condenser to capture the guitar.

I knew both mics would give me a decent result, even if I might have spent more time on mic choice and refining the placement for something I knew would be a final take. But I listened carefully: this part of the process can be a good time to see how a particular mic is pairing with a vocalist or guitar, thinking about things like sibilance and others issues that will make your life easier when recording in earnest later on.

Drums To Order

Because we’d worked to a click track, it was very easy for me to mock up any arrangement changes that Steve was considering, and we played around with a couple of options relating to the length of the instrumental section before settling on a plan. With the track mapped out in this form, we started to think about what other instrumentation would work, and we felt the guide track was in good enough shape for Steve to send to potential collaborators. The first stop was to put some drums in place, and Steve was keen to get his friend Stephen Gilchrist (also known as ‘Stuffy’) to play on this track. Stuffy plays drums for a number of artists and bands, including Graham Coxon, the Cardiacs and Charlotte Hatherley, and has a drum-recording setup at his own studio, so after a little discussion regarding style and drums sounds, we were able to send him the rough version of the track with tempo information and wait for the results.

When bouncing out rough mixes, I always mark and date where the rough mix was bounced from.The files arrived via an online file-sharing site, and we were presented with three drum takes to choose from, along with a few variations on fills and style. I downloaded the unprocessed multitrack drum files and, after a small amount of confusion regarding where the takes should start, mixed them fairly approximately in with the guide track. Steve was, for the most part, quite happy to trust my opinion with the drums, so I made what I considered was the best composite take, taking care to really think about the feel that was being established by the slight variations in groove and intensity. When you’re working with a great drummer, this can become very subjective, but even then it’s worth spending as much time as you need to get this right — the drums are just so important to the overall result of most productions. Apart from Steve questioning one fill, which we then swapped out for one from another take, we were both very happy with the part we now had in place.

When bouncing out rough mixes, I always mark and date where the rough mix was bounced from.The files arrived via an online file-sharing site, and we were presented with three drum takes to choose from, along with a few variations on fills and style. I downloaded the unprocessed multitrack drum files and, after a small amount of confusion regarding where the takes should start, mixed them fairly approximately in with the guide track. Steve was, for the most part, quite happy to trust my opinion with the drums, so I made what I considered was the best composite take, taking care to really think about the feel that was being established by the slight variations in groove and intensity. When you’re working with a great drummer, this can become very subjective, but even then it’s worth spending as much time as you need to get this right — the drums are just so important to the overall result of most productions. Apart from Steve questioning one fill, which we then swapped out for one from another take, we were both very happy with the part we now had in place.

I resisted the urge to do too much mixing at this stage — it’s something that’s always a real temptation, but I often find it counter-productive in the long run. I was keen to keep my DAW session as lean as possible for the time-being, as I knew there would be plenty of switching between my laptop and my main studio PC later. I also think it’s good practice to keep your CPU nice and happy if you still have plenty of tracking to do.

Filling Things Out

At this point, then, the track consisted of nothing more than the guide acoustic guitar and vocal recording, and Stuffy’s live drums. Me and Steve both agreed how much we liked how the guide acoustic guitar was sitting with the drums and were keen to see if Steve could re-create the same ‘vibe’ with an overdub. Using the guide track was an option, as I’d recorded it in a way that kept vocal spill to a minimum — although Steve was keen to point out that he’d made a few changes to the lyrics since we last got together! At the next recording session at Steve’s house, we focused our attention on trying out a few guitar options. We had a few different acoustic guitars available, and we also planned to see how a clean electric guitar might work. A nice period of experimentation followed, and we ended up with a few takes each of acoustic and electric rhythm guitars that, although not quite as nice as those in the guide track, would provide more than enough options if the vocal bleed on the original proved unworkable.

Updating The Vocals

The lead vocal was done with a Shure SM7 with a duvet hung behind the singer to reduce the room sound.We were both keen to get an up-to-date vocal part in place and, as I’d liked how it had worked on the guide track, I used the Shure SM7B once again. One of the good things about recording vocals with a broadcast-style moving-coil dynamic mic like this, which is designed for the voice to be delivered pretty close to the diaphragm, is that you end up with little ‘room sound’ in your recordings. I used the old trick of hanging a polyester duvet behind the singer — this usually does a great job of eliminating just enough unwanted reflections from your recordings. It’s not pretty, and Steve hated having my old duvet hanging up in his front room (this became a playful bone of contention!), but I insisted on using it, as I knew we wouldn’t regret it!

The lead vocal was done with a Shure SM7 with a duvet hung behind the singer to reduce the room sound.We were both keen to get an up-to-date vocal part in place and, as I’d liked how it had worked on the guide track, I used the Shure SM7B once again. One of the good things about recording vocals with a broadcast-style moving-coil dynamic mic like this, which is designed for the voice to be delivered pretty close to the diaphragm, is that you end up with little ‘room sound’ in your recordings. I used the old trick of hanging a polyester duvet behind the singer — this usually does a great job of eliminating just enough unwanted reflections from your recordings. It’s not pretty, and Steve hated having my old duvet hanging up in his front room (this became a playful bone of contention!), but I insisted on using it, as I knew we wouldn’t regret it!

Experienced artists like Steve, who have recorded many albums, tend to have developed a particular approach to vocal recording that they’re comfortable with. Whereas I tend to lean towards comping a decent ‘take’ from recordings, Steve is more used to working on getting one vocal take, and then listening back to a section, adding overdubs where necessary to refine it, and then signing off the resulting part. This took me a little outside my comfort zone: firstly, I knew that the time we had together in the same room was quite limited, and I wanted to make sure I had enough to play with and, secondly, it can be a little harder to judge how good a take is when recording remotely with headphones, as I was doing here. As always in such situations, good communication is crucial: doing my best not to unsettle Steve, I discussed my concerns with him. Our solution was to work in his usual way, but with Steve also letting me capture an additional take or two of the whole track, so that I had a few options to explore, should I feel at a later stage that I needed them. As the vocal was being double tracked, this would also give me plenty to play with when I got back to the studio.

At this stage in the proceedings, we sent a rough mix of the track out to bassist Chad Young, whose style we thought would work well with this track, and Steve also sent it off to other possible collaborators he had in mind.

Front Room Recording

This next recording session at Steve’s promised to be quite interesting. By this time, I’d already done a little work editing the vocal takes and a little basic (not plug-in heavy) mix work, to make sure the track was sounding presentable. We also had a bass guitar in place, as I’d got my fellow Cambridge resident Chad Young over to my own studio to lay down his already worked-out bass part with a minimum of fuss. Chad has decent facilities for recording at his place, but as he lives nearby it made more sense to work in person. It gave me the chance to capture a few different takes and to explore mic and bass-cabinet options (we also captured a DI feed).

When recording Justin Young’s electric guitar part, I took the precaution of taking a DI feed of the guitar signal. This enabled me to re-amp the guitar at a later date.Meanwhile, Steve had persuaded a few additional artists to contribute to the track — but all during a single day in Steve’s front room! The first guest to turn up was Justin Young, the singer in a band called the Vaccines. Justin had been brought in to play a lead-guitar part on the track, as well as to contribute some backing vocals. The last time I’d seen Justin was watching him perform on the Pyramid Stage at Glastonbury Festival, in front of about 50,000 people! It’s great that he’s also very comfortable working in this much more informal type of setup, despite being in a fairly high-profile band.

When recording Justin Young’s electric guitar part, I took the precaution of taking a DI feed of the guitar signal. This enabled me to re-amp the guitar at a later date.Meanwhile, Steve had persuaded a few additional artists to contribute to the track — but all during a single day in Steve’s front room! The first guest to turn up was Justin Young, the singer in a band called the Vaccines. Justin had been brought in to play a lead-guitar part on the track, as well as to contribute some backing vocals. The last time I’d seen Justin was watching him perform on the Pyramid Stage at Glastonbury Festival, in front of about 50,000 people! It’s great that he’s also very comfortable working in this much more informal type of setup, despite being in a fairly high-profile band.

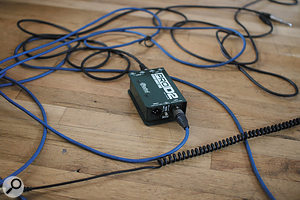

Our main priority with Justin was to get a melodic electric guitar part down, so once we’d got Steve’s old Telecaster in some sort of tune we set about playing with some ideas. We couldn’t turn up Steve’s little Fender amp too loud — not in a domestic environment like this — so despite it sounding OK with my Shure SM7B in front of it, I took the precaution of splitting the signal so I could also record a DI feed. I used this technique a few times on this album, as it meant I could work with what we liked on the day, but always had the option of re-amping things back at my studio to fine-tune amp sounds and mic placement.

The backing vocals were tidied up with the remaining ‘noise’ adding some extra vibe.We’d planned the session based on the theory that one of our busy guest musicians was bound to be running a bit late, so Steve had arranged for them to arrive in fairly quick succession. Of course, for the first time in living memory, all the contributors turned up at the appointed hour! Yet, despite Steve and I being concerned that this might prove awkward, it turned into a nice collaborative session, with singer/songwriter Emily Barker providing a nice backing vocal part, which Justin backed up with one of his own. As well as providing some fantastic accordion parts for another track on the album, Gill Sandell also delivered some great backing vocals.

The backing vocals were tidied up with the remaining ‘noise’ adding some extra vibe.We’d planned the session based on the theory that one of our busy guest musicians was bound to be running a bit late, so Steve had arranged for them to arrive in fairly quick succession. Of course, for the first time in living memory, all the contributors turned up at the appointed hour! Yet, despite Steve and I being concerned that this might prove awkward, it turned into a nice collaborative session, with singer/songwriter Emily Barker providing a nice backing vocal part, which Justin backed up with one of his own. As well as providing some fantastic accordion parts for another track on the album, Gill Sandell also delivered some great backing vocals.

For me, this session was a real highlight in this project. As Steve’s house got busier and busier, it became more and more difficult to maintain some sort of controlled recording environment, but in sessions like these it’s really important to get the balance right: you can always insist on redoing a vocal part because you can hear the kettle boiling in the background or some niggling little thing like that, but sometimes you need to prioritise keeping the fun alive and making progress! So I just got on with things — everyone remained happy, and the track progressed a great deal in the space of just a few hours.