Rod Wave (left) and Travis Harrington recording in a hotel room in Mobile, Alabama.

Rod Wave (left) and Travis Harrington recording in a hotel room in Mobile, Alabama.

Rod Wave’s chart‑topping album Soulfly was not only recorded in hotel rooms, but mixed and mastered on the road too. Travis Harrington was the engineer who made it work.

“In the music industry the relationship between the producer and the artist used to be central. But what’s happened more recently, particularly in rap, is that the relationship between the engineer and the artist has come more to the forefront. Many artists are now in the studio with just the engineer, who has to bring other skills to this partnership as well, like being able to produce and mix.”

Travis Harrington is talking about his work with singer and rapper Rod Wave, and his point has been echoed by several other engineers in the Inside Track series who have built long‑standing working relationships with particular artists. Among them are Patrizio Pigliapoco, who is engineer and mixer for Chris Brown, Bainz for Young Thug and Gunna, Tillie Mann for Migos and Lil Baby, and Todd Hurtt for Polo G, while examples outside rap include Josh Gudwin for Justin Bieber and Stuart White for Beyoncé.

Travis Harrington is talking about his work with singer and rapper Rod Wave, and his point has been echoed by several other engineers in the Inside Track series who have built long‑standing working relationships with particular artists. Among them are Patrizio Pigliapoco, who is engineer and mixer for Chris Brown, Bainz for Young Thug and Gunna, Tillie Mann for Migos and Lil Baby, and Todd Hurtt for Polo G, while examples outside rap include Josh Gudwin for Justin Bieber and Stuart White for Beyoncé.

The above‑mentioned artists thrive on a personal relationship with a trusted person in the studio to help them get their vocals and musical ideas down. This trend has been going on for a number of years, and in rap and particularly trap it is steered by another trend, which is that producers now make beats completely independently from the artists, and often don’t even meet them. Instead, artists develop their vocal parts to these beats with only their trusted engineer in the room.

Back On The Road

Harrington’s work with singer and rapper Rod Wave exemplifies this new trend. But there is another aspect of their work that sets them apart: Wave and Harrington record almost exclusively on the road, with the latter setting up his portable Mixing Is Art studio in hotel rooms and other non‑studio spaces.

“Rod and I first met in 2018, at 11th Street Studios in Atlanta,” recalls Harrington. “We hit it off, and jumped on the road together. Rod is kind of shy and not too keen on working in studios, while I am used to building a studio wherever. In the past you needed a studio to record in, but my generation is used to working anywhere, whether in a hotel room, a regular house, and so on. Rod and I built a process and a sound around that.”

Harrington started working with Wave around the time the artist was recording PTSD, his fifth mix tape. He’d signed to Alamo Records in June 2019, and the mixtape was released later that year. One track, ‘Heart Once Ice’, went viral on YouTube and TikTok, and kickstarted his career. The song ended up going two times platinum in the US. Like the rest of the album, it was mixed by star mixer Fabian Marasciullo. Harrington worked on a few of the songs on the mixtape, and from there his working relationship with Wave developed quickly.

“I recorded and mixed Rod’s first album, Ghetto Gospel, and then also Pray 4 Love, and most recently Soulfly. Ghetto Gospel is the first project that we did completely together. It is when we figured out exactly what we wanted to do. It is where Rod really started to realise the vision he has in his head, and started to home in on the sound he is after. We recorded the majority of the songs on these albums on tour. That is when most of the inspiration comes to Rod.

“We always find time to make records when on tour. You have to squeeze that in there. Rod is one of these artists who you have to catch in the moment, when he is going through the pain or whatever he’s going through when he’s writing these songs. He can be up all night after a show, and can call me at any time during the night. After the recordings I mix and master as we go, in my own time, on the road, using my Dre Beats Studio 3 headphones and occasionally my JBL 104‑BT speakers.”

Mixing is Art: a studio in a suitcase!

Mixing is Art: a studio in a suitcase!

These improvised circumstances haven’t prevented Harrington’s work with Wave sounding as good as anything in today’s marketplace, or Soulfly from reaching number one on the US album charts. Waves’ two previous albums also reached number two and number 10, and both went platinum in the US. “Back in the day it was about the equipment and the studio, the SSL desk and so on. But nowadays you can create your own environment, and that creates a better vibe, a better place for the artist to loosen up in and bring their own energy to the music and the recording. Working with Rod in hotel rooms gives me a real opportunity to capture that. He’ll call me from the hotel room above me, at three or four or sometimes at six in the morning, and we get to work!”

Travis Harrington: We always find time to make records when on tour... Rod is one of these artists who you have to catch in the moment, when he is going through the pain or whatever he’s going through when he’s writing these songs.

Dead Is Good

There are not many musicians, or engineers, who like to start work at six in the morning, but Harrington says he’s happy to function on just a few hours of sleep each night when on tour, and notes that over time the complains from other hotel guests about these early morning sessions have gone down, “maybe because the hotels have gotten better”.

Harrington also notes that he’s become so accustomed to setting up recording studios in unconventional places, that he can “walk into a hotel room and pretty much immediately let Rod know whether we will be able to get a good sound, or whether it will be super difficult. Typically I want carpet, soft wallpaper, more furniture, and have a sound that is as dead as possible. Certain hotel rooms have been amazing for this. I can then bring the life back in during the mix. But some hotel rooms are very ‘pingy’ which is what I call hollow, reflective rooms.

“The song ‘Brace Face’ on Ghetto Gospel, for example, was recorded in an almost empty hotel room, with hardwood floors, and cabinets of granite. So I had to put Rod underneath a blanket. He recorded that entire song sitting underneath a comforter, with the microphone in there with him. I’d rather have as little acoustics at the beginning, and then bring them back in during mixing, than have extra noise and not be able to get the vocal sound that I want. So I often use acoustic screens like the Aston Halo Shadow, Kaotica Eyeball and/or the Sterling Audio VMS Vocal Microphone Shield. But in general, it’s about the room sound, and microphone placement.”

Travis Harrington’s portable setup is based around an Avalon 737 channel strip, a Universal Audio Apollo 8 audio interface and a MacBook running Pro Tools. Note also the small JBL loudspeaker.

Travis Harrington’s portable setup is based around an Avalon 737 channel strip, a Universal Audio Apollo 8 audio interface and a MacBook running Pro Tools. Note also the small JBL loudspeaker.

In addition to the music, the vibe, and the acoustics, there is, of course, the gear. Harrington’s Atlanta studio, where he has not been for more than two years, has older gear like a Digidesign Digi 002 and a Mac Mini. As he’s been on the road with Wave for these two years, all his focus has been on the portable studio. “Lately I have been taking the most recent MacBook Pro with me, with Pro Tools, and a Universal Audio Apollo 8 soundcard, in some situations an Apollo Solo. My mic pre is the Avalon 737, and I use two microphones, the Telefunken ELA M 251 and a Neumann U87. My monitors are my headphones. I also bring Audio‑Technica and Audeze headphones, but my favourite headphones are the Dre Beat Studios 3. I have some Avantone CLA‑10 monitors, but I don’t take them with me any more. Instead I travel with the JBL 104‑BT’s.

“The Telefunken is my favourite mic for vocals. It gives me air that is unmatched. The Sony C800 also sounds very crisp, and I love it, but it is not the best microphone to use when you are travelling and have to set it up in a hotel room. Nevertheless, we recorded ‘Time Heals’, the last thing we released, on a C800, in Miami. I do not compress or EQ when I record, other than maybe add some high gain with the Avalon, to give the vocal a little more bite. Again, I prefer to add any treatments later on, during the mix.”

Big On Vocals

After the 6am phone call, or whenever it is, Wave and Harrington will sit down in the engineer’s hotel room and either record an idea that Wave has developed, or pull up a beat. “Rod writes in several different ways. There are songs for which he had written the song and we then had to find a beat to go with it. He writes a lot of things in his head throughout the day. The other way of working is that he finds a beat online, and starts to work with that. It’s just him and I, and we’ll go through a bunch of beats, and then it’s ‘Let’s try this,’ or ‘Let’s try that.’ Usually something will touch him, and then he will be able to move from there.

“When we were first working together, he would literally find beats on YouTube. Every now and then he still finds something on YouTube. Sometimes we’d go into the studio with some producers and figure out the sound Rod wants. I got into the game making beats, and I learnt engineering from there. That means that I can also step into the producer’s shoes when needed. The majority of the time what I do with Rod is help with the arrangement of the records, and vocal production. At the end of ‘Street Runner’, where you have the woman talking, that was not in the original version. I added that. I do a lot of production like that.

“But most of my work is about the vocals. Everything in hit music is about the vocals. The people who taught me were big on the vocal sound. So that is where my magic lies. When recording Rod’s vocals, it’s all about feeling. He’s not a trained vocalist, nor am I, so I don’t give technical instructions as to how to improve his vocal parts. But it works out because we’re after the feeling, rather than the perfect notes. We prefer lines that feel good over lines that are note‑perfect. He tends to sing a song all the way through a few times, and then we go over it line by line, section by section, punching in where necessary, always focusing on feel.

“I don’t like doing vocal comping afterwards, because I have nightmares that I may not have the perfect take, and once the artist is gone, I can no longer get a better take. So I prefer to have the vocal recordings finished by the time the artist walks out of the room, with the exact takes where I want them in the session. Vocal comping is kind of reconstructing a vocal, and I don’t want to do that. So once Rod and I are done punching in, the vocal recording is finished. I don’t need to go back and replace certain parts. I’ll have everything ready to start the mix.”

On The Dre Beats Studio 3...

Talk of the mix leads us straight back to the fact that Harrington mixes and masters all Rod Wave’s releases on his Dre Beats Studio 3 headphones. Doing final mixes and mastering purely on headphones is usually regarded as a big no‑no, and the Beats headphones in particular don’t have a great reputation for accuracy. For Harrington, however, thy are a reliable and indispensable benchmark, and mixing on headphones has become a way of life. “Yes, it is just how the cookie crumbles. I have learnt to mix in studios, and have been working in studios for a long time. When we went on the road I had to adapt, because I often don’t have a studio available to me to mix, yet the releases still need to be delivered. Because I have spent so much time in studios, I was able to train my ears and understand what was going on.

Travis Harrington: I learned to mix and master on headphones and my Beats [Studio 3 headphones] are my go‑to. I can’t work without them at this point. I finalise my work on them and don’t go to a studio afterwards, as crazy as it sounds. Many people don’t like the Beats, but for me they are perfect...

“So I learned to mix and master on headphones and my Beats are my go‑to. I can’t work without them at this point. I finalise my work on them and don’t go to a studio afterwards, as crazy as it sounds. Many people don’t like the Beats, but for me they are perfect. They give me the best sound. I have been using them since the day they came out. I have done all three albums on these headphones!

“I can mix anywhere. I have worked on certain records on the bus, which is possible with noise cancellation. But it’s still difficult, so most of the time I am mixing in a hotel room early in the morning before people get up. I just spend time with the record, constantly revisiting, checking, testing, and listening.

“I mix as I go. So four or five months down the road when it is time deliver the album, I have all the mixes done. I am not scrambling to go back and mix things later on. I also try to not take too much time in between the recording and mixing because of the vibe. I want to stay in the same vibe, and I want to still remember certain ideas I may have had while we were recording about what I was going to do in post‑production. I also do the mastering, in my Pro Tools mix session. I am not a trained mastering engineer, it came down to how Rod’s career blew up as we were going. I just needed to make it louder, and louder!”

Doing A Runner

Harrington illustrates his approach to mixing and mastering with the song ‘Street Runner’, which is the lead single of Wave’s Soulfly album, and has already gone platinum in the US. The song relies heavily on a sample of the song ‘Mixed Signals’ by Canadian singer Ruth B.

“Rod and I found the Ruth B sample,” recalls Harrington, “and we sent it to the producers LondnBlue and TnTXD, and they put a beat around it. As I mentioned earlier, I then added the final section with the girl talking. I first mixed the beat. Sometimes I get the track‑out of the two beat, sometimes it is difficult to get that. When I do get the track‑out, I tend to mix the beat in a separate session, as I did with this track. Mixing beats is not difficult. The vocals are more important.”

The Pro Tools Mix Window from the final version of ‘Street Runner’. With the beat already mixed to a stereo track (far left), all of the visible tracks are either vocal tracks or auxiliary tracks.

The Pro Tools Mix Window from the final version of ‘Street Runner’. With the beat already mixed to a stereo track (far left), all of the visible tracks are either vocal tracks or auxiliary tracks.

For this reason, Harrington supplied Pro Tools screenshots of his vocal mix session for ‘Street Runner’. [Download a large detailed version of this screenshot in the ZIP file.]

![]() travis-harrington-protoolsmix.jpg.zip

travis-harrington-protoolsmix.jpg.zip

At the top is his mixdown of the sample and the beat. From there the session is structured with Wave’s verse vocals (‘VS’), the track with the talking girl (‘Phone’), Wave’s break vocals, hook lead vocals, ad libs and backgrounds. Each of Wave’s vocal sections has its own aux track, and all vocals go to a ‘Vox Aux’. At the bottom of the session are Harrington’s aux effect tracks, with various synchronised delays, ‘Big Verb’, another delay track called ‘Aux 1’, and finally his Master Fader.

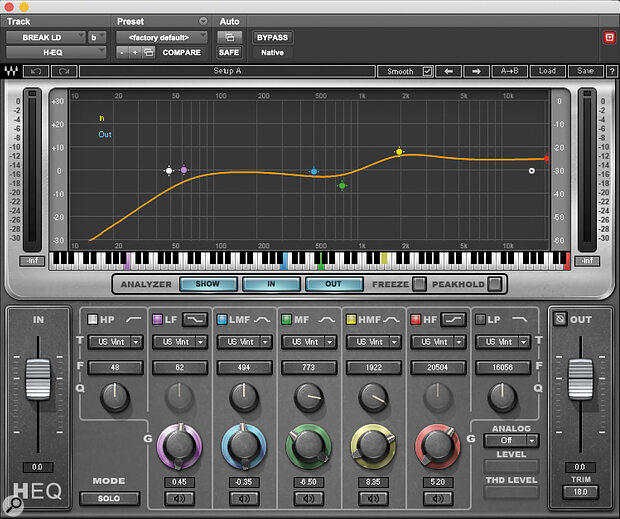

Travis Harringon’s extensive use of Waves plug‑ins seems apt for an artist called Rod Wave! Here we see the H-EQ in action.

Travis Harringon’s extensive use of Waves plug‑ins seems apt for an artist called Rod Wave! Here we see the H-EQ in action.

The ‘Street Runner’ mix session is notable for the large amount of plug‑ins and sends on most vocal tracks, with up to nine inserts and four sends. The vocal signal chains are very similar, consisting for the most part of Antares Auto‑Tune EFX followed by Waves H‑EQ, Sibilance, RCompressor and RDeEsser, Avid D‑Verb, and Waves CLA‑2A and RVox. The sends go to three of the delay aux tracks and the ‘Big Verb’ aux. There’s some variation with a Waves Doubler and an additional Waves De‑Esser.

Waves RCompressor.“Rod’s style does not rely on Auto‑Tune that much,” explains Harrington. “Some of his sound comes from a natural rawness of not quite hitting some notes, and I don’t necessarily look to correct that with Auto‑Tune. I often keep it loose. I also use Melodyne sometimes, but it’s only for one or two notes, and never set on the entire performance. The second plug‑in, the H‑EQ, is one of my favourite EQs, and I often boost Rod’s vocal around 2kHz and above 10kHz for some clarity and bite, and I take out around 500Hz, because that’s where it gets muddy.

Waves RCompressor.“Rod’s style does not rely on Auto‑Tune that much,” explains Harrington. “Some of his sound comes from a natural rawness of not quite hitting some notes, and I don’t necessarily look to correct that with Auto‑Tune. I often keep it loose. I also use Melodyne sometimes, but it’s only for one or two notes, and never set on the entire performance. The second plug‑in, the H‑EQ, is one of my favourite EQs, and I often boost Rod’s vocal around 2kHz and above 10kHz for some clarity and bite, and I take out around 500Hz, because that’s where it gets muddy.

“The Sibilance takes out some esses, and I then squash the vocal pretty hard with the RCompressor, and then there’s a De‑Essser. Some engineers take issue with placing plug‑ins in this order, but it works for me. I’m not into rules when it comes to mixing, as you can tell from the name of my company. I don’t think there are rules in art. You need to learn them, and then you can break them.

“Another difference in my mixes is my use of the D‑Verb on the audio track, instead of using it on a send. I like to coat the vocal in reverb. After this I compress again, with the CLA‑2A, which again is against the rules. What this does in combination with the reverb is brings the vocal out in front of the reverb, yet it also brings the reverb with it. It gives me this airy, reverb‑coated vocal, that is still up front and does not get lost in the reverb. It is kind of a weird trick.

“The sends have my standard delays, which are part of my template, using plug‑ins like the Avid ModDelay and Waves H‑Delay, and then there’s the Big Verb aux, which has the H‑Delay, Studio Reverb and D‑Verb. I don’t know who made Studio Reverb. I found it when I was digging online, it may have been free. I love it. I’ve set it to ‘Large Theater’, which is a really damp reverb. I’m an excessive reverb user. I do things with reverb that many people don’t even try. For me reverb is the be‑all and end‑all when it comes to vocals and adding depth. Reverbs can also be used to add volume.

“The sends have my standard delays, which are part of my template, using plug‑ins like the Avid ModDelay and Waves H‑Delay, and then there’s the Big Verb aux, which has the H‑Delay, Studio Reverb and D‑Verb. I don’t know who made Studio Reverb. I found it when I was digging online, it may have been free. I love it. I’ve set it to ‘Large Theater’, which is a really damp reverb. I’m an excessive reverb user. I do things with reverb that many people don’t even try. For me reverb is the be‑all and end‑all when it comes to vocals and adding depth. Reverbs can also be used to add volume.

“Of course I tailor the settings on this effect chain for each vocal. There’s also a Waves Doubler on the ad libs, because I wanted to spread them out wider. I also took out the ‘Big Verb’ on some tracks, so these vocals are a bit dryer and more in your face. Another interesting thing I did in this mix was to add a filter to the girl phone voice at the end, via the aux track ‘End FX Aux’. I added the Waves OneKnob Filter, and the RCompressor and D‑Verb, and then automated the OneKnob to get some movement going in the sound.

“The master fader is where I mastered this track. I added the Waves Kramer Master Tape plug‑in for some saturation, and then some control from the Waves L2, and then the L3 and the McDSP ML4000 mastering limiter. I usually use the ML4000 to get the loudness from my master. It’s the loudest mastering plug‑in that I could find!

Waves Kramer Master Tape plug-in lives on Harrington's master bus, to provide some saturation.

Waves Kramer Master Tape plug-in lives on Harrington's master bus, to provide some saturation.

“The focus of this mix, in addition to getting the vocal right, was to make sure that all the elements, the sample, the vocals, the beat, and the girl talking, are all working together, and yet also have some contrast between them. Using samples is just the name of the game today. You get everything from many different sources all the time, it’s part of the process. The main thing is something Dave Pensado once told me, which is about making everything you do sound musical.”

Travis Harrington

Travis Harrington was born in 1988 and grew up in Atlanta, where he made beats in his teenager years, starting out in his mum’s bedroom. In his late teens he went to the Los Angeles Recording School, after which he interned at Larrabee Studios, home of top mixers Jaycen Joshua and Manny Marroquin. After returning to Atlanta, Harrington became an assistant at Triangle Sound Studios, the facility of legendary producers Tricky Stewart and Terius ‘The‑Dream’ Nash, which is part of their company RedZone Entertainment. Harrington worked there with Josh Gudwin and America’s number one vocal producer Kuk Harrell, amassing credits on recordings by Katy Perry, Drake and Justin Bieber.

“I was taught,” notes Harrington, “by Tricky Stewart and the mix engineers that he used, Jaycen Joshua and Manny Marroquin. Kuk also had a certain process as a vocal producer that I was able to be a part of. When I came to RedZone, they were on a great run, and getting all these Grammy Awards, like for Beyoncé’s ‘Single Ladies’. They did so many great records, and I witnessed their process. That helped me to find my own sound and approach.”

Harrington went independent in 2011, and opened his own Mixing Is Art facility in Atlanta in 2015. The name, he says, is his brand, and encapsulates his belief that mixing is not purely a technical process, and that achieving perfection, technical or otherwise, is not a crucial objective. In this respect, endless polishing also is not his thing. “When you like music, you don’t necessarily go, ‘Oh, there’s an imperfection.’ Instead, there’s something that touches you. I always try to stay in that realm, whether working in a hotel room or a studio. There are times when you can work on a song for two weeks straight, and at some point you can take the love out of it, you can take the art out of it. So it has to be a happy medium between the art and the technique. What you do needs to be somewhere in the middle. Much as I like to be perfectionist, we can’t neglect that it simply comes down to: ‘Does it sound good, or not?’”