This month, we were tasked with overhauling the sonics of a mix while still retaining the magical 'vibe' of the original. But 'chasing the demo' can be a risky tactic!

There's nothing wrong with chaining together several EQ plug‑ins in search of the best tone. In this remix, the lead vocal went through three EQ plug‑ins on the way to the master bus: Reaper's ReaEQ and Universal Audio's 4k Channel and Helios Type 69. The first dealt surgically with a couple of spectral-balance issues, while the other two plug‑ins each provided their own unique timbral shading.

There's nothing wrong with chaining together several EQ plug‑ins in search of the best tone. In this remix, the lead vocal went through three EQ plug‑ins on the way to the master bus: Reaper's ReaEQ and Universal Audio's 4k Channel and Helios Type 69. The first dealt surgically with a couple of spectral-balance issues, while the other two plug‑ins each provided their own unique timbral shading.

When I first heard this month's song, 'Infernal Machine', the evocative lead vocal and unusual arrangement immediately caught my ear, bearing testament to Lawrence Eldridge's self‑professed admiration for the intricately layered work of producers such as Nigel Godrich and Neil Davidge. However, Lawrence acknowledged that there were problems with the clarity and definition of the mix, and was also concerned about the bass end — and he'd only been able to work on Sennheiser HD650 headphones and Yamaha NS10 monitors, neither of which can really resolve extreme low frequencies.

Chasing The Demo

I agreed to see if I could achieve a more satisfactory result — though not without some trepidation, because there was a certain indefinable magic to Lawrence's original mix, and that kind of thing can be well‑nigh impossible to recapture after overhauling the sonics. Every producer I talk to seems to have a couple of horror stories about situations where they were called in to make a commercial‑sounding production of an unusably lo‑fi demo, while retaining the essential vibe that the artist, manager, and/or A&R person had fallen in love with. 'Chasing the demo' like this is fraught with difficulties, because the 'vibe' usually arises from a complex interaction of factors that aren't really repeatable. The best you can hope for is that the new version will have enough of its own unique spark to eclipse the memory of the demo. Otherwise, you need to salvage some elements of the demo, layer them over your new production, and hope that they bring some of the desired flavour with them.

I used both approaches to some degree, but started by concentrating on emphasising the individual character of each of Lawrence's sounds as much as possible, in the hope of compensating for any dilution of the original mix's personality. I could happily fill this whole article with a blow‑by‑blow account of all of this, but I don't think anyone else would really benefit from such specifics, because it all essentially boils down to this: I added effects and wiggled controls more or less at random until each track sounded somehow funkier than it did to start with!

There's not much to be learnt from that for your own productions, but there are a few general guidelines I can suggest when you're after 'character' processing like this, especially in heavily electronic styles where audiophile notions of cleanness and transparency aren't high on the list of priorities. The first thing to say is that extreme settings I'd rarely use for more technical mix‑balancing are very much back on the menu if I'm trying to super‑charge a raw track's individuality. For example, while enormous EQ boosts aren't really appropriate for transparent spectral balancing, cranking up the gain controls of an analogue‑style EQ squeezes much bigger changes in tone and attitude out of it than a kid‑gloves approach. It's a similar story with analogue‑style compressors: driving them really hard stamps their unique timbral mark more heavily on a signal, and normally unpalatable amounts of gain‑pumping and distortion can often become the main benefit of the processing.

There's not much to be learnt from that for your own productions, but there are a few general guidelines I can suggest when you're after 'character' processing like this, especially in heavily electronic styles where audiophile notions of cleanness and transparency aren't high on the list of priorities. The first thing to say is that extreme settings I'd rarely use for more technical mix‑balancing are very much back on the menu if I'm trying to super‑charge a raw track's individuality. For example, while enormous EQ boosts aren't really appropriate for transparent spectral balancing, cranking up the gain controls of an analogue‑style EQ squeezes much bigger changes in tone and attitude out of it than a kid‑gloves approach. It's a similar story with analogue‑style compressors: driving them really hard stamps their unique timbral mark more heavily on a signal, and normally unpalatable amounts of gain‑pumping and distortion can often become the main benefit of the processing.

You still need to be careful of the 'louder is better' pitfall, though: if your processing makes the signal louder, you'll instinctively think that it also sounds better, even if it doesn't. I was tickled to discover that I'd walked right into that trap myself during this remix, by getting too carried away boosting with U‑He's Uhbik Q equalizer. By combining a wide peaking boost at around 400Hz with high and low shelving boosts at around 90Hz and 2kHz respectively, I ended up pretty much boosting the track's overall level, rather than changing its tone. Homer Simpson has a monosyllabic reaction for just such eventualities...

Creative Or Technical?

This is the bus compressor Mike used on his master outputs. What appears to be extremely severe processing was moderated in two important ways: a high‑pass filter reduced the kick‑drum's prominence in the compressor's side‑chain; and the plug‑in's internal compressor mix control was set to 51 percent, to prevent the gain‑reduction squashing all the life out of the main transients.

This is the bus compressor Mike used on his master outputs. What appears to be extremely severe processing was moderated in two important ways: a high‑pass filter reduced the kick‑drum's prominence in the compressor's side‑chain; and the plug‑in's internal compressor mix control was set to 51 percent, to prevent the gain‑reduction squashing all the life out of the main transients.

It's also worth saying that it's sensible to try to differentiate creative and technical applications of a given type of effect in your mind while working. There are good reasons for using a chain of several different EQs, for example, where analogue‑style plug‑ins are delivering subjective tone, while more transparent and precise digital or linear‑phase EQs deal with frequency balance and masking issues. The best example of this in 'Infernal Machine' was the lead vocal part, which I first EQ'ed with Reaper's general‑purpose ReaEQ plug‑in, high‑pass filtering to get rid of low‑frequency rubbish and also scotching an ugly pitched resonance at 308Hz, using a surgically narrow peaking cut. I then tried out a variety of different modelled analogue EQs before deciding that boosting at 3.8kHz and 17.8kHz with Universal Audio's 4k Channel Strip gave a coldness and hardness that worked, while a 3dB, 2kHz peak and a 5dB, 50Hz low shelving cut from the same company's Helios Type 69 EQ brought the mid-range forward in a nicely focused way. ReaEQ couldn't have delivered those kinds of tonal changes, but neither were the modelled analogue plug‑ins as well suited to the troubleshooting tasks.

By the same token, it's easy to create dynamic‑range problems for yourself when you're using heavy‑handed dynamics processing to maximise a compressor's tonal side‑effects, so it's perfectly legitimate to employ more 'technical' dynamics processing to address any such problems down the line. Tom Lord‑Alge gave a good example of this back in SOS April 2000: "To make a vocal command attention, I'll put it through an Teletronix LA3A and maybe pummel it with 20dB of compression, so the meter is pinned down. If the beginnings of the words then have too much attack, I'll put the vocals through an SSL compressor with a really fast attack, to take off or smooth out the extra attack that the LA3A adds.”

In this remix, it was my master-bus processing that necessitated the greatest amount of technical dynamics troubleshooting. I was using heavy compression over the full mix because it was clear to me from the original version that compressor gain pumping was a key part of Lawrence's vision. I'd fired up an instance of URS Console Strip Pro and tried out several different classic-compressor emulations to find the one that seemed to pump in the most subjectively suitable way — a fast‑attack, fast‑release emulation of the Neve 2254, as it turned out, but with the ratio reduced from 100:1 to 10:1.

The multi‑band compression setting used to flatten over‑prominent stick transients in the overheads involved a combination of super‑fast time constants and an infinity:1 ratio.The first unwanted side‑effect was that the kick drums were triggering the gain‑reduction more than I wanted, so I fixed that by switching CSP's filters into the compressor's side‑chain, cutting everything below 40Hz. The next thing to deal with was that by the time the pumping was working nicely, the punchiness of the drum peaks was suffering. Fortunately, I'd just updated my version of CSP, so I could use the compressor section's new built‑in wet/dry mix control to let some of the transients through.

The multi‑band compression setting used to flatten over‑prominent stick transients in the overheads involved a combination of super‑fast time constants and an infinity:1 ratio.The first unwanted side‑effect was that the kick drums were triggering the gain‑reduction more than I wanted, so I fixed that by switching CSP's filters into the compressor's side‑chain, cutting everything below 40Hz. The next thing to deal with was that by the time the pumping was working nicely, the punchiness of the drum peaks was suffering. Fortunately, I'd just updated my version of CSP, so I could use the compressor section's new built‑in wet/dry mix control to let some of the transients through.

Even when the general sound of the compression seemed to be working, there were occasional balance issues. The lack of bass and drums in the introduction, for example, meant that the compressor was hardly working at all, so I had to use automation to stop the voice and guitar coming over too loud there. The other problem was that the apparent volume of each electric-guitar stab varied depending on whether or not it coincided with a drum hit, because of the bus compressor's rhythmic ducking of the backing track. My solution was to mult out all those stabs which occurred on drum hits, and then fade them higher in the balance to compensate for the ducking.

Multi‑band Compression & Side‑chain Dynamics

U‑He's Uhbik‑T tremolo plug‑in was used to pull rhythmic guitar-picking transients out of their recorded‑in reverb. There's more to learn with this plug‑in than with most tremolos, but it is great for this kind of mixing trick.

U‑He's Uhbik‑T tremolo plug‑in was used to pull rhythmic guitar-picking transients out of their recorded‑in reverb. There's more to learn with this plug‑in than with most tremolos, but it is great for this kind of mixing trick.

This remix required more than its fair share of unusual dynamics processing to achieve the final balance, and there were two instances where I used multi‑band compression: once to increase the amount of sub‑150Hz energy in the bass part, while at the same time keeping this region more tightly under control; and once to remove stick‑noise transients from the drum overheads, knocking about 8dB off peaks around 5kHz with a very fast attack and release. Side‑chain triggering also came into its own, with three different tracks being controlled according to the level of the main snare sample. The first of these was the Addictive Drums snare track, which was adding nice spill elements to the mix, but when I faded it up to feature these more strongly, the track's main snare hits overpowered the main sample in a way I didn't like. I first tried just compressing the track to duck the snare hits, but this sounded odd where the Addictive Drums snare played fills without the sample. By using a compressor keyed from the snare sample instead, I was able to duck the Additive Drums snare track only when the sample was playing. Job done! In much the same way, I ducked the snare level in the overhead mics, while a further side‑chain triggered gate achieved the opposite effect for the room mics, independently increasing the snare ambience.

I also used another application of side‑chain triggering for the vocals. As I said, if you're 'chasing the demo', there are times when it helps to layer some of the demo elements alongside the new production, and that's what I did for the lead vocals. In general, I liked the vocal effects Lawrence had used, and it seemed like reinventing the wheel to recreate them from first principles. I wasn't as keen on the tone of the dry element of Lawrence's vocal, though, so I decided to run my own processed version of the raw track in tandem. The reason I needed the side‑chain dynamics was because when the vocal effect tails seemed to me to be at the right level, Lawrence's processed lead vocal seemed to be fighting too much with mine. By compressing Lawrence's effected track in response to a side‑chain feed from my dry track, I could duck his processed vocal sound out of the way only when it mattered, leaving intact the nice effect details between syllables.

Tremolo & Automation Or Dynamics Processors?

Rather than using another layer of compression, Mike decided to simulate the effect of compression pumping more controllably by creating a pattern of dynamic automation in Reaper.

Rather than using another layer of compression, Mike decided to simulate the effect of compression pumping more controllably by creating a pattern of dynamic automation in Reaper.

The last dynamics trick I used is something I was able to bring out of retirement courtesy of U‑He's Uhbik‑T plug‑in. There are some situations where you want to emphasise only those elements of a part that occur on specific beats, or beat sub-divisions, and this is something for which Uhbik‑T's flexible tempo‑sync'ed tremolo is perfect. There was an arpeggiated guitar part that Lawrence had, unfortunately, recorded with quite a lot of reverb, such that it was difficult to use its nice rhythmic texture without clouding over other parts. By setting Uhbik‑T to a sawtooth tremolo waveform and sync'ing its oscillation to a sixteenth‑note rhythm, I was able to pull down the reverb levels between each note in a very predictable way, using the plug‑in's Depth control. A similar tempo‑sync'ed technique helped to inject better rhythmic definition into an over‑fuzzed guitar part in the outro, again by dipping note sustains with the sawtooth LFO. I particularly like Uhbik‑T in this role, because of how it lets you fluidly adjust the phase and waveform of the tremolo LFO to map its action exactly onto rhythmic events, even if they're slightly ahead of or behind the beat, and how you can adapt the tremolo to more complex rhythmic patterns using the built‑in sequencer. You can achieve similar effects by carefully drawing patterns with level automation, but Uhbik-T does a more elegant job.

This screenshot shows how all the added textural samples were laid out across the song, and how level fades and automation were employed to keep this aspect of the arrangement in motion.I did resort to drawing an automation pattern for the gain‑pumping effect on the drum overheads and room mics during the choruses (0:49‑1:08 and 2:01‑2:20). The pumping had been a feature of Lawrence's mix that I really liked, but I found in my remix that the dynamics processing that worked for the track as a whole didn't give a strong enough effect for those sections. By this point, the overall dynamics processing was already fairly precariously balanced, with lots of interaction between the individual parts and the master bus compressor, so I was concerned that trying to implement the pumping sound in the usual way (with a compressor strapped over the drums submix) might upset the whole applecart — and I decided to fake the pumping instead, using automation.

This screenshot shows how all the added textural samples were laid out across the song, and how level fades and automation were employed to keep this aspect of the arrangement in motion.I did resort to drawing an automation pattern for the gain‑pumping effect on the drum overheads and room mics during the choruses (0:49‑1:08 and 2:01‑2:20). The pumping had been a feature of Lawrence's mix that I really liked, but I found in my remix that the dynamics processing that worked for the track as a whole didn't give a strong enough effect for those sections. By this point, the overall dynamics processing was already fairly precariously balanced, with lots of interaction between the individual parts and the master bus compressor, so I was concerned that trying to implement the pumping sound in the usual way (with a compressor strapped over the drums submix) might upset the whole applecart — and I decided to fake the pumping instead, using automation.

Between each main drum hit I drew an upwards level ramp, resetting the gain as the next hit arrived. With a simpler drum pattern I could have used Uhbik‑T, but I wanted the simulated pumping to react more intelligently to variations in the pattern. Rather than automating the fader, I used a dedicated gain plug‑in (GVST's GGain), so that I could keep longer‑term automation moves separate from the pattern effect. This also meant that I could easily assess the effectiveness of the pumping by bypassing the plug‑in. Achieving the right dynamic response took a little experimentation, and in the end the most effective configuration used Reaper's slow‑start automation curve for the gain ramps, applying 12dB of gain at each ramp's peak.

Less Reverb, More SFX

A gated patch from Stillwell Audio's Verbiage added big‑reverb density and width to the snare, but without the clutter of a big‑reverb tail.

A gated patch from Stillwell Audio's Verbiage added big‑reverb density and width to the snare, but without the clutter of a big‑reverb tail.

One of the things that I felt worked least well in Lawrence's mix was the reverb effects, which seemed to swamp the overall production. As in most such cases, the basic problem was that Lawrence seemed to want a thick and complex texture, but hadn't included quite enough of those characteristics in the raw tracks themselves. I set about layering in a selection of background textures to try to fill out, rather than wash out, the production sonics.

It pays to choose sounds that reflect the nature of the song, and I took my inspiration here from the title 'Infernal Machine', searching through media sound‑effects libraries for machine/telecoms‑style SFX. With a shortlist of a few dozen of these in my mix project, I could then drag each one around to see which sections of the track it might best suit. It's just as important to consider the track's arrangement in this instance as at any other time. By the time I'd finished, I had a dozen tracks of SFX running through the track: one 'room tone' background ambience throughout to glue everything together; one slightly surreal wide‑stereo atmospheric texture through most of the track to underpin the overall emotional tone; six 'transition' effects (in other words, sounds which slowly increased in level towards section boundaries in order to increase the momentum between sections); and four tracks of more obvious technological weirdness for the outro section, which begins at 2m 25s.

This might seem like quite a lot of extra information, but you have to bear in mind that most of the time these tracks were at a fairly subliminal level in the mix, and only a subset were playing at any one time. I was also careful to keep the SFX levels from remaining static on those occasions where they were upfront enough to draw the listener's active attention, because a bit of ebb and flow in this aspect of the arrangement means that the listener's attention is encouraged to wander between the different sounds, so that each one doesn't seem to pall or dominate over time.

With that done, there was much less need for reverb and other blending effects, and the only obvious reverb I used was on the snare drum, inspired by the roomy‑sounding snare of Lawrence's original mix. However, while I liked the extra density and spaciousness that a big reverb added to the snare, I felt that a long reverb tail was out of keeping with the mood of the mix, and that it could also potentially clutter the sound as a whole. My compromise was to use a gated reverb patch, which I was able to adjust fairly freely for thickness, timbre, and stereo width without having to worry about any tail. The excesses of the 1980s have prejudiced many engineers against gated reverb, but the effect can work really well in situations like these (as long as you don't overdo it!), so I'd advise against rejecting it out of hand.

My choice of weapon in this instance was Stillwell Audio's Verbiage, because I figured its less naturalistic algorithmic reverb generation and built‑in gating would suit the task well. High‑density early reflections and a medium room size gave me the width and timbre I was after without any need to adjust the internal Output Width parameter, although I took advantage of the plug‑in's high‑pass filtering keep the low end clear below about 165Hz. It only remained, then, to set up the gating controls to achieve the desired burst length, switching the plug‑in's default detection setting to 'dry' so that it triggered from the plug‑in's input rather than its output. I prefer it that way, because then reverb adjustments don't mess with the gating action.

Machine Dreams

One of the biggest challenges of mixing is juggling conflicting creative and technical demands when processing, and many rookie mixes fall at that hurdle. On the one hand, it's important to give yourself the creative freedom to break all the rules in search of inspiring sounds, without feeling bound by technical consequences; but on the other you need to be able to exercise some control over the results of these creative enterprises if you're going to combine them effectively into a cohesive artistic statement that's suitable for your target market.

The fact that the lion's share of a typical Mix Rescue column typically deals with technical mix decisions shouldn't be seen as undermining this central point either — it's because those kinds of choices are more rational, so their explanations have much more to offer from a learning perspective. Hopefully, this month's remix helps redress the balance somewhat, by highlighting that there is space for no‑holds‑barred experimentation within the mix process — even if that makes life more difficult from a technical perspective.

Tuning Tweaks

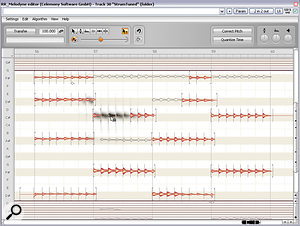

In order to get the best out of Melodyne Editor's DNA processing when re-tuning a strummed guitar in this remix, Mike was careful to correct any errors in the software's automatic note detection process before properly getting down to the correction work.

In order to get the best out of Melodyne Editor's DNA processing when re-tuning a strummed guitar in this remix, Mike was careful to correct any errors in the software's automatic note detection process before properly getting down to the correction work.Although I considered tuning the main vocal part, I decided that the few tuning inaccuracies I detected actually contributed to the generally unnerving nature of the part, so I took a deep breath and slapped down my inner control freak. The strummed electric-guitar part, though, was wince-worthy in the tuning department, and up to a few months ago would have been unsalvageable, because the guitar strings were out of tune with each other. However, with Melodyne Editor's polyphonic processing, I could snatch victory from the jaws of defeat!

There are two main difficulties when using Melodyne Editor like this. The first is that the automatic note-detection isn't infallible, so you need to check that it's interpreting the notes correctly. Though straightforward to do, this is time‑consuming — so if you don't want to die of boredom, try, where possible, to copy and paste corrected sections rather than correct the whole part. The other problem is that the complex upper mid-range harmonics of overdriven electric-guitar parts reveal Melodyne's processing side‑effects more readily than most other sounds: they typically get duller, and exhibit a hint of what sounds like chorusing. My workaround is to run a high‑pass filtered version of the unprocessed guitar part alongside the corrected one, using it to add some of the original high‑frequency definition back in. In this case, I filtered at around 4kHz, stacking three 12dB/octave high‑pass filters on top of each other in Reaper's ReaEQ to achieve a steep 36dB/octave slope. This reduced the amount of pitched information in the filtered track, to avoid undue conflict between the corrected and uncorrected parts, and also zoned the additional frequency energy into the most useful region.

Rescued This Month

This month's song was created by Lawrence Eldridge, working under the Obscuresounds moniker, a project started about 10 years ago when he bought his first analogue synth (an Octave Cat). He describes his style as "bastardisation: a little rough round the edges, but lovingly experimental and surrealist”, and name-checks a variety of influences including Beck, Massive Attack, Ladyhawke, Hot Chip, LCD Soundsystem, Ladytron, Portishead, New Order, Radiohead and Air.

He started the song 'Infernal Machine' in Ableton Live, mangling his own voice with effects to create the unusual 'female' lead. Drums were a composite of parts programmed in XLN Audio's Addictive Drums, but the snare was supplemented using a sample from an old Commodore Amiga's 8‑bit PCM sound chip, which also spawned the bass line. Lawrence added various processes via Universal Audio's UAD plug‑ins and the Waves catalogue, as well as funnelling the vocals through something of a collector's item: the Publison DHM 89 B2 stereo delay/detune effect. The project was exported to Nuendo for tweaks and send effects, and the final mix was printed to analogue tape.

Remix Reactions & Audio Files

Lawrence: "Having heard the results, I'm extremely happy with all of the changes, and Mike's pretty much nailed the sound I was after! Its refreshing how much the track has opened up and become more vibrant by separating the different elements. Mike's done an excellent job getting the track to come across as refined and catchy, and I especially love the alterations towards the end with that chaotic S&H sound and the additional 'infernal machine' lyric — it's one of those moments where you think 'why didn't I do that in the first place?'. I also really like the changes made to the drums. They're a lot cleaner, which is great — very Ladyhawke! In my own version I simply bounced the entire drum set and ran it through an LA2A plug‑in (mainly to save on time!), but this mix has shown me that it can be much more rewarding to put everything on its own channel for separate processing.

"Overall I've learnt that whilst quirky effects work well for added character, it's also good to take a step back and use them in moderation, because in doing so the track retains its dynamic character, rather than getting bathed in processes. This is something that can only be learnt by working with other profesisonals and seeing how they interpret a track. Hopefully from a technical and creative standpoint I'm slowly 'getting there', and I've taken so much from this experience which will help me continue to churn out music.”

If you'd like to form your own opinions on the mix, you can find before and after audio files at /sos/jul10/articles/mixrescueaudio.htm.