Even a basic understanding of chords, melody and harmony can help your dodgy demo become a polished production...

There's plenty of head‑scratching to be done when choosing recording equipment, and helping you to choose and use your gear is what makes this magazine tick. But a surprising number of the reader demos that are sent in to SOS Towers fall down at an earlier hurdle — the music itself.

Musical Answers Or Production Polish?

We've all been there. We've sat in our studio with a sequencing project open, and pondered on one of these questions:

1. Why does this sound wrong?

2. What can I do to make it sound less predictable?

3. Where could I take this next?

4. What more can I add to it?

The possible answers to those questions may lie in recording and production techniques, or they may be musical — and the ways in which these answers might interact are endless. Before you assume that there's some polish you can add using plug‑ins, then, it's well worth considering whether the track might benefit from musical changes.

To anyone who's grown up learning music simply by listening to records and learning to play an instrument by ear, or programming parts on a piano‑roll editor, the idea of learning musical theory can seem dry and off‑putting, or even daunting. But it really needn't be. In this article, I'll take you through a number of useful musical tools and techniques that you can apply to your own compositions — and I promise I'll keep staves, musical manuscripts and notation well out of sight!

Tones, Semitones & Scales

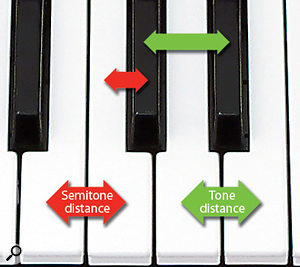

Most of us own a MIDI keyboard of some sort that offers 12 semitone-spaced notes to choose from, and a selection of scales you can play that begin on each of those notes. A semitone's distance is easy to see: it's the next physically closest note to another, going up or down, and, to paraphrase the late King Of Pop, it don't matter if they're black or white. So, the distance between the E and F keys is a semitone (because there's no black note between them), the distance between C and C# is a semitone, and two such semitone 'steps' (E to F#, for example) make one tone's distance. Scales can be thought of as steps, measured in tones (two keys) and semitones (one key)

Scales can be thought of as steps, measured in tones (two keys) and semitones (one key)

It's probably easiest to think of scales as ladders, with set distances between the steps, each of which are measured in semitones and tones. The most simple (and arguably predictable‑sounding) ladder is that of a major scale, which follows a Tone-Tone-Semitone-Tone-Tone-Tone-Semitone pattern. The note on which the major scale's ladder starts is particularly important, because it tells you what major key you're working in. This is also true of minor scales, which brings us neatly on to a useful musical device...

Major To Minor

Grasping the pattern and sound of the major scale will unlock a huge selection of other scales, the most common of which is the 'relative minor' scale. To find this, start from the first note of a major scale (let's say G,) then count down three semitones from that note. Starting from this new note (in G's case, E), play the same (G) major scale notes you originally chose. You are now playing a minor scale. Thus, the relative minor scale of G major is E minor. Each major scale has a relative minor — and it's such a useful musical shortcut. You could also try giving this minor scale a new twist by 'sharpening' the seventh note (in other words, pushing the seventh note in the scale up a semitone). This will create a 'harmonic minor' scale, which is rich in harmonic tension, and arguably brighter sounding than the original minor scale.

A La Mode

Chords in the key of D major, using the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes (left) and adding the 7th (right).

Chords in the key of D major, using the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes (left) and adding the 7th (right).

Major-scale notes can also produce other scales, with weird, ancient names. The seven modes of the major scale are the most commonly used 'alternative' scales in Western music, and they each have a distinctive flavour, making them a great addition to any musician's spice cabinet. A mode of a scale is just a way of saying "same notes, different starting point”. So the second mode of a G-major scale would still use the same notes, but the start‑point is an A instead of a G.

"But what difference does it make where you start from?” I hear you ask. Actually, it makes all the difference in the world if you think of this new start‑point as an independent offshoot: you're not playing G major any more, you're playing A Dorian. Everything now centres on the A, and if you imagine A as the root note of a new scale, the resulting sound is a minor scale, but with a sharpened sixth note. This might not strike you as much of a change, but it can make all the difference in the world when you start building chords and melodies. In short, then, try moving the starting point of a major scale, and give that note its own gravitational pull. You'll have unlocked a whole new set of magic ladders from which to build new tunes. And there are other ladders to explore: whole tone, diminished, altered, melodic minor... The list goes on.

Complete A‑Chord

Once you've selected your ladder, you can choose any combination of notes from it to create chords. If you work systematically, the scale‑tone chords of each ladder will take the 1st, 3rd, 5th and (sometimes) 7th notes as chord number 1, and will move upwards, creating chords in an orderly fashion. So, for example, in the key of D major you'd construct the chords shown in the table below.

As an alternative to this systematic approach, you could always work a little more randomly with your 'ladder'. You'll find that most combinations of notes will probably still sound OK. In fact, even if you were to fall off the ladder completely, there's always the chance that you'll stumble upon a wonderful‑sounding 'mistake'. (That's how I first discovered an E7#9 chord, for example.) In short, in music, as in so many walks of life, the rules are there for a good reason, but there are also good reasons to break or ignore them on occasion.

Investigate Inversions

On a keyboard, chord inversions are useful tools to employ, because:

1. Their use can add a different 'flavour' to what is essentially the same chord.

2. They make the transition between chords in a progression much easier for your fingers.

3. Using them in a chord progression will make your playing sound more seasoned and mature.

Essentially, all you're doing is taking a chord and 'jumbling' the order of the notes. Rather than doing this randomly, though, you're doing it in a pre-ordained fashion. For example, instead of playing an E-minor chord in the root position (from bottom to top note: EGB) you could put the E on the top of the chord, and play GBE. Or you could put the G at the top, playing BEG. EGB is the root position, GBE is the first inversion, and BEG is the second inversion.

Incidentally, if you jumbled up the notes thus: EBG, GEB, or BGE, then not only would these be difficult to fit into most people's handspan (important if you're trying to program a realistic keyboard part!), but they wouldn't technically be classed as inversions. Rather, they'd be 'wide voicings'. The general rule to remember is to take the bottom note and put it on the top, as this will always give you chord inversions, each of which has an attributed number.

To take point number two from above a little further, here's a practical example of how you might choose to use inversions to string your chords together. Let's say that you were working in the key of C and had a simple progression of C, Em, Am, F. You could play all these chords in their root position. It might sound a little basic, and on a keyboard instrument you'd have to move your hand around the block chords like a clumsy toothed digger-bucket piling into the keys — but it could be done. Alternatively, you could treat it like a puzzle, first identifying what notes are common to one chord and the next. In the case of C and Em, the E and G note would be present in each. Having played the C chord, leave your fingers invisibly glued to the E and G notes, and search out the remaining required note with a free finger. You don't have to be a contortionist, as there will be a note close by that fits the bill.

Instead of playing CEG, then moving your hand and playing EGB, you are now hopefully playing CEG, then BEG. It sounds smoother, and saves hopping around the keyboard unnecessarily. Continue in a similar fashion, and you'll likely end up with the sequence illustrated rightabove. Chord inversions provide a quick and easy way to make your compositions sound more accomplished.

Chord inversions provide a quick and easy way to make your compositions sound more accomplished.

Not all linking chords share notes, but you'll very often find there's an inversion of one chord or another that's within easy reach of the preceding one: it's just a matter of detective work. Once you've built up a few links, some patterns will emerge, and you'll be more confident with your movement around chords.

You Chose Chord Number…

You'll hear the same chord progressions crop up again and again. Look at the table on the opening pages of this article, which shows chords one to seven in the key of D Major. If you try playing the first, fifth, sixth and fourth chords on that table, it should sound something like the Beatles' 'Let It Be'. The Australian comedy group Axis of Awesome's act (check out their official video at http://youtu.be/oOlDewpCfZQ) demonstrates just how many pop songs use such one-five-six-four sequences from a major scale. Similarly, jazz music is littered with 'two‑five‑one' chord progressions (you'll sometimes see the chord numbers written in Roman numerals to avoid confusion with scale degree numbers). Similarly, chords one, four and five are the backbone of 12‑bar‑blues the world over. In other words, a lot of Western music follows a systematic route: the scale tone chords mentioned previously get placed into songs in common ways, and we become familiar with the sound of their interlocking relationships.

But what if you want to get away from what everyone else is doing? Back in the first half of the 20th century, a clever chap called Arnold Schoenberg developed an analytical chart, with which he aimed to make sense of which keys were easiest to link with each other, owing to common notes or relationships between them. This 'Chart of the Regions (top right) Arnold Schoenberg mapped the relationship between musical keys in his 'Chart Of The Regions' . The above chart shows the relationship of all keys to C Major: if you're in any doubt about how to use it, the flow diagram (right) will hopefully shed some light on the matter!

Arnold Schoenberg mapped the relationship between musical keys in his 'Chart Of The Regions' . The above chart shows the relationship of all keys to C Major: if you're in any doubt about how to use it, the flow diagram (right) will hopefully shed some light on the matter! Arnold Schoenberg, 1948.Photo: Florence Homolka

Arnold Schoenberg, 1948.Photo: Florence Homolka If you're in any doubt about how to use Schoenberg's chart, this diagram should help you understand how it works!, published a few years after his death, shows a logical way of moving between keys (and therefore chords) in order to get from one key to a (potentially) distantly related one. Amongst other things, it highlights two concepts that are valuable tools in any tune‑writer's box: parallel major/minor keys, and closely related keys.

If you're in any doubt about how to use Schoenberg's chart, this diagram should help you understand how it works!, published a few years after his death, shows a logical way of moving between keys (and therefore chords) in order to get from one key to a (potentially) distantly related one. Amongst other things, it highlights two concepts that are valuable tools in any tune‑writer's box: parallel major/minor keys, and closely related keys.

Parallel Lines

The key of A major has three 'sharps' included, whereas the key of A minor has no sharps or flats (because its relative major is C). It's plain to see that these keys don't share all their notes, but their shared root note means that they have a very strong bond. This 'A' note makes a transition between these two keys very strong, like a bridge that makes it possible to explore new harmonic territory. Once you've crossed the bridge from major to minor (or vice versa), you're free to explore all the other chords in this new parallel key.

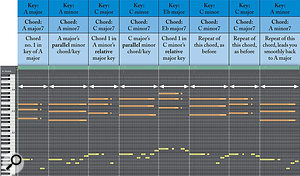

There's a MIDI file on the SOS web site (see box for details) that illustrates how this general idea could work in the context of a progression. The piano and bass parts are illustrated in this example, with guidance on each chord change. Both parallel-minor and relative-minor relationship movement make it easy to move between chords in a progression.

Both parallel-minor and relative-minor relationship movement make it easy to move between chords in a progression.

What's The Difference Between...?

The fact that certain keys share all but one note is woven into the Chart of the Regions I mentioned earlier. For example, C major is very close to G major, because the only difference is that the latter requires the F to be sharpened. Thus these keys are closely related, and moving between them is easy. The chord of G major is the fifth chord in the key of C major, and the fourth chord in the key of G major is C major. Share and share alike...

Another common way of linking keys and chords together is impossible to illustrate on the Chart, but makes total musical sense in a chromatic way. The (ahem) 'classic' moment on Top Of The Pops or The X Factor when a boy band stand up from their high stools, just after the middle eight, is inextricably linked to a key change. Love it or hate it, there's no denying that it's an uplifting point in the song: just when you think it can go nowhere else but that earworm of a chorus ad infinitum, there's a feeling of exhilaration (or so the writers would hope), when a chromatic key change makes its grand entrance.

Usually, while the last line of the middle eight hangs on chord five of the song's key and the lads are holding a lovely long note, the chord is shifted up a semitone's distance — thus leading the song into chord one in the key a semitone above the original, where the chorus can again be blared out in all its glory before the song finishes in a triumphant fade‑out.

This is arguably the most common use of chromatic movement in pop music, and could be called a cliché, but there are other examples too. Any chromatic movement between melody notes, bass notes, chord notes, whole chords or keys can be a wonderful tool to employ, and a pleasing way of breaking the rules of Schoenberg's chart. The repetitive outro of Chaka Khan's 'I'm Every Woman' gives you a perfect example of how you can bounce around chords chromatically to build and release harmonic tension.

In short, all keys and chords are able to join hands with others, and there are many ways of making this happen. Find a way to make it happen and you should be able to break out of your musical rut, and keep your listener in the enjoyment zone.

Different Hats

It's worth stating here that each chord in a key has its own set of musical wheels — by which I mean that it can take off in its own direction in the middle of a song, spring‑boarding to a new selection of chords and notes — and this alone can make your music stand out harmonically from the crowd.

For example, if you were to write a song in E major, you might pick the chords one, two, five and four for the verse, chord four in this case being A major. If you're wondering where to go next, what's to stop you crossing the bridge to the parallel A minor, which spawns further chords in its own key? The A-minor chord also has the option of donning a different hat — perhaps it could play instead at being chord two in the key of G major, or chord three in F major, opening up each of these new keys to exploration. (See table top right to visualise these and other possible A-minor chord 'hats' clearly.) Or perhaps that original A‑major chord could modulate up a semitone if it fancies, introducing a new family of notes by way of chromatic movement.

Just One Note

To strip it back even further, the A-note within the aforementioned A-major chord could be sustained through the melodic line while you choose a new chord for it to fit into — instead of being the root note of an A-major chord, it might become the top note of a D‑minor chord, or the middle note of an F‑major chord. Each chord shift would make sense because of that shared A note. This world of exploration falls under the umbrella of 'chromatic‑mediant' chord relationships, and can create a nicely filmic, other‑worldly feeling in a song. If you're left in any doubt about this, I've created another MIDI file — again downloadable from the SOS web site — that illustrates how this could work.

In summary, then, chords can lead you anywhere you like, and provided you have a map of the territory, you'll have a good idea of which way will work out best for you. rather than relying on trial and error.

What Are You Implying?

A lot of the time in music, the key to success is not in the notes you put in, but in those you choose to leave out. Just as in art, where you might fuss around with brushstrokes and end up obscuring the original zest of your piece, in music you can end up overcrowding a solo section or melody line, leaving no room for clever twists.

One of these twists works purely on the basis of what isn't there. Because each key shares some notes with another, you might choose to emphasise their shared notes in a particular way. For example, within the key of A major exist all the right notes to construct an E-major pentatonic scale: E, F#, G#, B, C#. Just playing those notes in a melody section, over the chord of A, can have an interesting 'ghosting' effect. You're not doing anything particularly clever there, but there is nonetheless a feeling that you are somehow playing in two keys at once. This construction has a particularly tasty effect if you create a chord sequence around a modal scale such as C dorian (which takes its notes from the B-flat major scale), and emphasise the aforementioned sharpened sixth note (see the earlier 'A La Mode' section) within a 'ghosting' scale such as F-major pentatonic.![]() 'Ghosting': the key of A major (above) contains all the notes (highlighted in pink) that are needed to construct an E-major pentatonic scale. Playing that scale over the chord of A Major can create an interesting 'ghosting' effect.

'Ghosting': the key of A major (above) contains all the notes (highlighted in pink) that are needed to construct an E-major pentatonic scale. Playing that scale over the chord of A Major can create an interesting 'ghosting' effect.

Bass‑ically speaking

There's an interesting game of cat and mouse to be played between the chord‑playing keyboard fraternity and bass guitarists, and in the world of programmed music you can play this game with yourself. For instance, the initial idea of playing an E-minor-7 chord might have its world turned upside down if a bass player decides to stick a C beneath it, because it transforms it into a C-major-9 chord, whether the keyboardist likes it or not. That's worth remembering if you get fed up with the way things are sounding chord‑wise: you can always try tucking in some different bass notes underneath your chords. Examine the table on the previous page for ideas of how this could work, as it might just turn your song in a fresh direction.![]() Ghosting is particularly interesting when used with a modal scale. This example shows an F major pentatonic scale within the notes of a C dorian scale. Placing an emphasis on the sharpened sixth will enhance the effect.

Ghosting is particularly interesting when used with a modal scale. This example shows an F major pentatonic scale within the notes of a C dorian scale. Placing an emphasis on the sharpened sixth will enhance the effect.

Head‑scratching Conclusion

Writing songs is a craft and an art, and the theory behind making music is there to support your ideas and progressions, not to inhibit and rule it. But the more you can draw on the concepts discussed here, the more confident you can be of a great result. Let your instinct guide you, by all means, but if you back it up with a good awareness of what you're doing, the music‑writing world can be your oyster — and that should benefit all of your productions. Who'd have thought 12 humble semitones could bring so much joy and variety to your music?

Kate Ockenden's musical career spans BBC commissions, independent film scores, keyboard playing, singing and university lecturing. Her recent jazz/funk EP was deemed 'outstanding' by jazz expert Richard Niles. For more information, go to www.kateockenden.co.uk

Different Hats Of An A-minor Chord (Triad)

| Key: A minor Chord No: 1 |

Key: G major Chord No: 2 |

Key: F major Chord No: 3 |

Key: E minor Chord No: 4 |

Key: D minor Chord No: 5 |

Key: C major Chord No: 6 |

| 1. A min 2. B dim 3. C maj 4. D min 5. E min 6. F maj 7. G maj |

1. G maj 2. A min 3. B min 4. C maj 5. D maj 6. E min 7. F#dim |

1. F maj 2. G min 3. A min 4. Bbmaj 5. C maj 6. D min 7. E dim |

1. E min 2. F#dim 3. G maj 4. A min 5. B min 6. C maj 7. D maj |

1. D min 2. E dim 3. F maj 4. G min 5. A min 6. Bb maj 7. C maj |

1. C maj 2. D min 3. E min 4. F maj 5. G maj 6. A min 7. B dim |

Changing Chords By Adding A 'Wrong' Bass Note

| This chord type... | ...and a bass note which is... | ...makes this chord | Example |

| X major (triad) | 3 semitones down from the root note | Y minor7 | F/Ab‑C‑Eb |

| X major (triad) | 4 semitones down from the root note | Y major7 #5 | C/E‑G#‑B |

| X minor (triad) | 3 semitones down from the root note | Y minor7 b5 | D/F‑Ab‑C |

| X minor (triad) | 4 semitones down from the root note | Y major7 | Ab/C‑Eb‑G |

| X aug (triad) (aug=augmented=major chord with sharpened 5th ) | 3 semitones down from the root note | Y minor maj7 | A/C‑E‑G# |

| X dim (triad) (dim=diminished=minor chord with flattened 5th) | 4 semitones down from the root note | Y dom7(dom=dominant=major triad plus flattened 7th) | C/E‑G‑Bb |

| X major 7 | 3 semitones down from the root note | Y minor9 | C/Eb‑G‑Bb‑D |

| X minor7 | 4 semitones down from the root note | Y major9 | C/E‑G‑B‑D |

| X major add9 | 3 semitones down from the root note | Y minor7 add11 | A/C‑E‑G‑D |

| X diminished7 | 4 semitones down from the root note | Y dom7 b9 | D/F#‑A‑C‑Eb |

| X major7 b5 | 4 semitones down from the root note | Y dom7 #5 #9 | C/E‑G#‑A#‑D# |

| X minor7 b5 | 4 semitones down from the root note | Y dom9 | G/B‑D‑F‑A |

This table shows how it's possible to use the interaction of the bass guitar and other parts to play a game of 'cat and mouse', making the music more interesting.

MIDI File Examples

The author has generated MIDI files that could help you to better understand some of the points in this article (see main text for details). They can be downloaded from /sos/oct11/articles/facethemusicmedia.htm.