Our second instalment draws on the work of Alan Blumlein, to explain how we can audition and evaluate different stereo‑miking techniques.

In Part 1 of this series on stereo miking techniques we looked at the intentions behind recording in stereo, and how the human ears/brain work out the location of an audio source in the real world, using three primary mechanisms: inter‑aural level differences (ILDs), inter‑aural timing differences (ITDs), and spectral cues from the sound reflections off the shoulders and pinnae. The reason we needed that background information is that, when we capture and replay stereo recordings, our aim is to recreate those auditory locational cues, either as accurately as possible, or in a way that is pleasingly believable.

So, before moving on to examine different stereo microphone techniques, we need to consider how the ways in which we audition two‑channel stereo recordings emulate the real‑world experience. And for that, we need to look in particular at the pioneering work in the 1930s of Alan Dower Blumlein.

Until such time as humans can be upgraded with direct Bluetooth reception to the auditory processing centre in the brain, we only have two options for listening to stereo recordings: loudspeakers or headphones/earbuds. Both approaches have their merits and disadvantages, but they each interface with the human hearing system in dissimilar ways, so result in significantly different experiences.

By their very nature, headphones (and earbuds) isolate each ear, which can only hear the signal presented via its own channel. This is in contrast to real life where both ears always hear a sound source with different levels, timings and frequency responses, as previously explained. So, this aural exclusivity is inherently unnatural, and the most obvious result is sounds being perceived as existing within the head — along an imaginary line between the ears, rather than in the space around us. There are ways to resolve that problem, though, and I will return to that in the future.

In the meantime, listening over loudspeakers is where stereophony began, and the majority of stereo microphone configurations are optimised for this format... so that’s where I’m going to start.

Loudspeaker Stereo

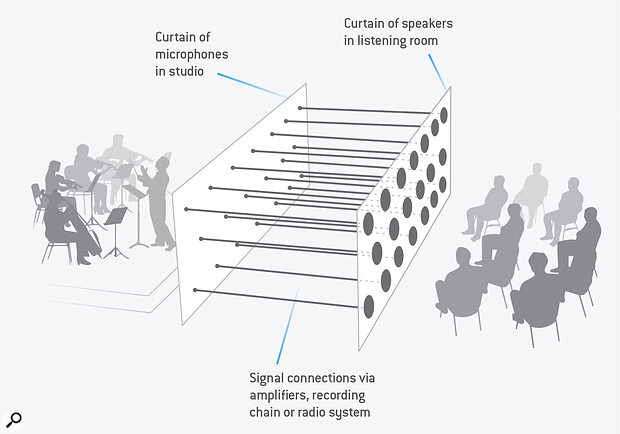

To most people, ‘stereophonic’ implies two loudspeakers, but it wasn’t always that simple. Back in the early 1930s, Dr Harvey Fletcher and his team, working for Bell Labs in America, were experimenting with multi‑channel sound recording and reproduction. His initial work used a large curtain of many microphones, arranged laterally and vertically in front of a stage, effectively sampling the combined sound wavefront projected from an ensemble on that stage. Each of those microphones was linked individually (via suitable gain stages) to a correspondingly located loudspeaker in a separate listening room, the idea being to reconstruct the original sound wavefront, preserving all directional information from the sound sources on stage — a system which was known as the ‘Curtain of Sound’.

This system actually worked very well, but of course it was highly impractical — especially since multi‑channel recording and transmission hadn’t yet been invented, from the recording and transmission points of view! Fletcher and his team therefore simplified the system, eventually deciding that three microphone/loudspeaker channels, arranged as left, centre and right, in a horizontal line, was the minimum arrangement for recreating acceptable locational information.

To demonstrate this new format to the public in March 1932, Fletcher arranged a live relay, using telephone lines to route the three audio channels from the Academy of Music in Philadelphia to the Constitution Hall in Washington. The Conductor in Philadelphia was Leopold Stokowski, who had a great interest in improving recorded sound, and he went on to help Disney develop its bespoke surround‑sound system, Fantasound, which was launched in a roadshow tour of the Fantasia film to public theatres across the USA in 1940.

The results of Fletcher’s public demonstration were considered impressive, but the technical difficulties of managing even three channels — maintaining their critical phase, timing and level relationships — eventually curtailed further development. From a commercial perspective, another significant problem was how to create a mono recording for release on a 78rpm disc. Downmixing all three mic channels to mono resulted in unpleasant comb‑filtering, while only using the centre channel lost information from the sides, compromising the overall balance. Solutions were found in time, of course, most notably with the superb Mercury Living...

You are reading one of the locked Subscribers-only articles from our latest 5 issues.

You've read 30% of this article for FREE, so to continue reading...

- ✅ Log in - if you have a Digital Subscription you bought from SoundOnSound.com

- ⬇️ Buy & Download this Single Article in PDF format £0.83 GBP$1.49 USD

For less than the price of a coffee, buy now and immediately download to your computer, tablet or mobile. - ⬇️ ⬇️ ⬇️ Buy & Download the FULL ISSUE PDF

Our 'full SOS magazine' for smartphone/tablet/computer. More info... - 📲 Buy a DIGITAL subscription (or 📖 📲 Print + Digital sub)

Instantly unlock ALL Premium web articles! We often release online-only content.

Visit our ShopStore.