The 24‑channel Oracle at SSL’s HQ in Begbroke, Oxfordshire, which formed the basis of this review.

The 24‑channel Oracle at SSL’s HQ in Begbroke, Oxfordshire, which formed the basis of this review.

It’s been decades since the last commercially successful digitally controlled analogue mixing desks could be bought new. Now, console‑automation legends SSL believe the time is finally ripe for their return...

A few weeks before the June launch of SSL’s new Oracle console, I drove down to their headquarters in Begbroke, Oxfordshire, where I had the opportunity to lay hands, eyes and ears on a 24‑channel specimen, and spent several convivial hours quizzing designer Niall Feldman and his colleagues on the finer points of their creation. I’m told it’s the culmination of many years’ R&D — I gather the team started batting around ideas for this and the ORIGIN at the same time and the ORIGIN came out three years ago!

Famously, SSL were pioneers of computer‑based console automation. Other digital control systems may have existed, but their 4000 B console, released in 1976, was one of the earliest to have computer‑based automation built in, and the 4000 E that followed in 1979 took the concept much further; it was, I believe, the first desk to combine total parameter recall, level automation, tape transport control and comprehensive channel EQ and dynamics. (For more about how this worked in practice, check out our 2022 video demo: https://sosm.ag/ssl-4000e-video).

Those early recall systems ushered in a revolution in audio production, but weren’t what we’d call ‘digitally controlled analogue’. As that video shows, there was a lot of manual alignment of controls involved in the recall, so while accurate and impressive, it certainly wasn’t instant or automatic. In the years since, SSL have continued to make analogue consoles, along the way improving specs and introducing new features to adapt them to the changing nature of music production. But it’s arguable that their underlying console design philosophy hasn’t really changed that much over the years: “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it...”

Back To The Future?

SSL founder Colin Sanders set out a vision for digitally controlled analogue consoles way back in 1985 — arguably, the Oracle finally delivers it.

SSL founder Colin Sanders set out a vision for digitally controlled analogue consoles way back in 1985 — arguably, the Oracle finally delivers it.

In some respects, that could be considered surprising. Forty years ago (1985) SSL founder Colin Sanders published a booklet, The Future of Audio Console Design: A Report To The Recording, Post‑production And Broadcasting Industries. In it, he set out his vision for how recording console design should evolve to meet the changing needs of those industries, essentially arguing that more flexibly configurable consoles were required to accommodate the need for so many channels and facilities, and that the only way to achieve this was by doing away with physical controls that directly altered circuit parameters. Instead, he argued, some kind of assignable remote‑control facility would be essential: the audio routing and processing might be analogue or digital — he gave equal page space to both — but, either way, the approach to control interface design and ergonomics would be the same. From a quality point of view he preferred analogue, probably partly because it was familiar to him and partly because DSP really was still in its infancy in 1985. And in his consideration of analogue electronics, he discussed at length the pros and cons of various devices for altering analogue circuit parameters, including FETs, opto‑fets and MDACs — the last being widely employed in SSL products today, of course.

At the time, SSL concluded that digitally controlled analogue consoles were not yet commercially viable, which is why they opted to develop their existing technology. Of course, they long ago embraced digital audio processing in other product lines, and have, in their mixers, embedded digital facilities like automatable faders that can serve as DAW control surfaces. But, although they did release digitally controlled EQ for the SSL 4000 in the early ’80s, it wasn’t until 2022 that they launched a fully digitally controlled analogue device: the Bus+, reviewed in SOS May 2022 (https://sosm.ag/ssl-bus-plus). The Oracle builds on that experience and the company’s control surfaces to finally deliver something like Sanders’ vision: an inline mixing console with a fully analogue signal path, but with everything being digitally controlled.

The Inbetween Years

Of course, some other companies did pursue this approach. In the UK, Calrec Audio’s VCS console (1985) was used widely in BBC TV broadcasting, where the ability to instantly recall settings was very beneficial. It was superseded by the Series‑T in 1991, and the control‑surface assignability concepts were later carried into the company’s digital consoles. Around the same time in the USA, Harrison developed their SeriesTen, which used five assignable knobs per channel strip to control all channel functions. Like the Calrec, every function could be saved and recalled, with full automation, and the company went on to develop further digitally controlled analogue consoles: the SeriesTen B (1989) and the Series 12 (1994). Trident announced their ultimately unsuccessful Di‑An in 1986 (only a couple were ever made) and in the same year, French company SAGE presented their take on the concept at an APRS event. Euphonix arrived at the party a little later, with probably the most commercially popular models: their Crescendo (1990) evolved into the CSII and later the CS2000 (1993) and CS3000 (1997), before they eventually turned their attention to digital mixers.

So the Oracle’s core operational concepts — and even the use of MDACs for remotely controlled variable resistances — are not entirely new. But having said that, we’ve seen 30 years of improvements in technology and manufacturing methods since then, and the Oracle attempts to bring analogue up to date in a way that hasn’t previously been possible. And I have to say that I reckon they’ve done a bloody good job of it!

SSL view it as a replacement for their AWS948 (which remains available), and it seems to have been designed to fit well with the furniture for that range...

What’s The Big Idea?

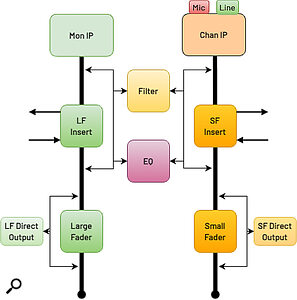

The signal flow on all channels is pretty configurable, with the ability to move inserts and EQ position, to place sends pre‑ or post‑fader, and to assign the filter and EQ to either of two channel paths.

The signal flow on all channels is pretty configurable, with the ability to move inserts and EQ position, to place sends pre‑ or post‑fader, and to assign the filter and EQ to either of two channel paths.

Digitally controlled analogue is more expensive to implement than conventional analogue or purely digital gear and, naturally, the Oracle is pitched at the top end of the professional studio market. SSL say they view it as a replacement for their AWS948 (which remains available), and it seems to have been designed to fit well with the furniture for that range — not a coincidence! But it will also be jostling for attention alongside flagship analogue consoles from the likes of Neve, Rupert Neve Designs and API, not to mention SSL’s existing range.

For those like me who can only dream of financing such things, it’s worth noting Niall’s suggestion to me that lots of the R&D that went into developing the Oracle project should soon make its way into other, more affordable products (which I assume means outboard gear...). But for high‑end commercial studios, universities and other multi‑user environments who can choose to spend big, SSL believe that the Oracle offers several advantages that justify the asking price. And I think they have a point.

For example, engineers today might have to deliver multiple mix versions, and revisit project sessions to make revisions. Fast, accurate recall is essential for this sort of thing, and thanks to SSL’s patented ActiveAnalogue technology, the Oracle manages the sort of near‑instant total recall that we normally associate with digital mixers. A full session can be loaded in an impressive 3‑4 seconds — quicker than the loading time for a typical DAW project! Such speed can free up session time in the studio. So too can the accompanying Mac/Windows O‑Control software, which can be used offline to prep console settings remotely, before the studio ‘money clock’ starts ticking. The physical format also permits more analogue channels in a smaller footprint and with tidier cable management, which could all have knock‑on implications when specifying a control room.

All of which is really good news — if you’re happy with the features. Generally, I expect most engineers will be, and I’ll discuss various facilities that impressed me below. But while there’s a lot to appreciate, some might well have preferred to see channel dynamics processors included — these were a key, much‑loved feature on older SSL consoles. Of course, you can patch in other outboard. What’s more, there are now several manufacturers making digitally controlled analogue outboard gear and patchbays. It’s not hard to imagine the day when we can fire up the lot along with the Oracle simply by loading our DAW session; a tantalising prospect!

Rack ’Em Up

The Oracle has three main components: a digital control console, remote control software for Mac and Windows machines, and the analogue electronics, which sit in elegant 13U racks. The part in the pictures that looks like a mixer is, in fact, almost entirely dedicated to digital control, with just its talkback mic, headphone jack and aux input being analogue. The O‑Control software caters for both recall and automation — it can link with your DAW to allow DAW‑based automation of the Oracle — but can also be used offline to set up new projects or edit existing ones. But let’s start with those rack units, which connect to the control console via a network cable.

The Oracle’s analogue electronics are almost all housed in two 12U rack units (three for the 48‑channel version), which connect to the control console via a network cable.

The Oracle’s analogue electronics are almost all housed in two 12U rack units (three for the 48‑channel version), which connect to the control console via a network cable.

There might be two or three rack units, depending on the configuration (two for a 24‑channel console; three for a 48‑channel one). Either way, one rack is reserved for ‘centre section’ (it’s on the right!) functions, while the others provide the inline input channels. The analogue I/O on the rear of these racks is mostly on DB25 D‑subs, and it’s anticipated that the console will be used with a studio patchbay. The racks could fit under the console if desired (you have the option to put it on a desk or on legs), but because of how they connect, they could be placed elsewhere in the control room or in a separate room entirely.

There’s lots of electronics in these boxes, but the power consumption stats make decent reading: a full rack consumes 400‑600 Watts, and a low‑power standby mode consumes only 40W. Nonetheless, some components can run quite hot, and that requires cooling fans. Thankfully, in the several hours I had with the demo console, with two rack units located about eight feet (2.4m) away, noise was simply not an issue; the noise target for professional recording studios is defined as NR25, and I’m told that with the fans running at full pelt the Oracle manages NR23. Niall described to me the obsessive detail the team had paid to thermal efficiency and fan‑speed management that made this possible. In essence, the arrangement is akin to that in a computer tower, with an air intake at the bottom/front and fans drawing air towards an exhaust at the top. He said that particularly careful attention was given to the placement of specific heat‑generating components, so as to take full advantage of the resulting airflow.

Channels & Busses

Before exploring the control surface, it makes sense to explore the functions it’s intended to control, and what’s on offer is a highly configurable version of more typical SSL analogue consoles. All the main input channels are inline, with a mic/line channel input and line‑level monitor input each having its own signal path. That gives you 48 ‘regular’ inputs at mixdown (double for a 48‑channel Oracle), and there are further inputs in the centre section should you really need more.

The mic preamps are another refinement of SSL’s PureDrive design, which itself evolved from the preamps in the original Duality console (2006). I like them: they’re quiet and, as well as gain, pad and polarity inversion facilities, you can choose a ‘clean’ or ‘coloured’ sound, courtesy of variable harmonic distortion. Each channel’s two signal paths have their own gain and fader stage, stereo pan facility, insert point and direct out, and the latter’s position is moveable pre/post fader. Each inline channel also has one variable high‑pass filter and a separate four‑band EQ section, and those can be assigned to the channel or monitor path, and toggled pre or post the insert in the chosen path.

I found the EQ particularly intriguing because it takes full advantage of the precision made possible by digital control. As you’d expect from SSL, the top and bottom bands are switchable between bell and shelving types, while the two others are bells. What’s novel, though, is that they can be switched between fixed‑ and proportional‑Q types, so effectively allow you to change the EQ between the 4000 E and 4000 G ‘voicing’ . You could see this as a gimmick, but I think there’s more to it: engineers who’ve used those consoles can set the behaviour to match their preference/experience — potentially a selling point that gets more engineers through the studio doors. There’s interesting potential here, too: the filters were reportedly designed to allow wider bandwidths than needed, meaning it will be possible in future to emulate other EQs’ characteristic shapes.

Naturally, the channels can be routed to various destinations. There are 10 mono aux busses, and thanks to the digital control these can be ganged to give you up to five odd/even stereo pair aux sends (the channels themselves can, of course, be linked in similar fashion). There are also 16 mono track busses that can be used independently and/or routed to stereo groups in pairs. These could be thought of as subgroups when mixing, but these groups also have external inputs, inserts and direct outputs so could be used for various other applications.

While SSL have been able to make some interesting accommodations for those working in immersive audio (of which more in a moment), the Oracle is at heart a stereo console, and any channels, including the track busses, can be routed to any or all of four stereo mix busses. Bus A is intended as the primary stereo mix bus. The secondary ones have an insert point, an output fader and line‑level output, and are routable to bus A, so can be used downstream from all your subgroups for parallel master‑bus processing. Bus A is more feature‑rich. For one thing, it boasts two insert points, one pre‑fader and the other post, so you could, for instance, mix into the sweet spot of an analogue EQ in the first slot, and then use the master fader to ride the mix levels into a compressor. But you may well not feel the need to patch in an external compressor, because bus A features the latest version of SSL’s The Bus+ stereo VCA compressor, complete with its two‑band dynamic EQ. As in most places on this console, the order in which you place these stages is fully configurable.

While we’re on the subject of processing, all the stereo busses also feature M‑S encoding/decoding and have a stereo width control. The former allows you to patch in dual‑mono processors to act separately on the Mid and Sides components of a stereo signal. Surprisingly, the latter is more than a simple M‑S balance control: it ranges from 0 (dual mono) to 150% and works well.

The default on‑screen bar meters, in SSL orange, align with the physical channel control strips.

The default on‑screen bar meters, in SSL orange, align with the physical channel control strips.

Monitoring, Foldback & Comms

The Oracle provides outputs for up to five sets of stereo monitors, and on the digital control console you have all the expected facilities in terms of selecting the speakers, setting the control room level, and the various solo options those who’ve used other SSL consoles will find familiar: PFL, AFL, solo‑in‑place and solo‑in‑front. You’ll also find a headphone output conveniently located at the front‑right of the console, and it’s possible to route PFL/AFL exclusively to your headphones so that playback on main monitors isn’t interrupted. (This feature is hidden, to prevent accidental selection.)

Three stereo foldback feeds (A, B and C) allow you to build cue mixes easily, and typically carry the mixes from aux 1+2, aux 3+4 and aux 5+6, respectively. But these busses can also pick up the control room monitor signal, if you wish, or one of the four external stereo inputs — like the headphone out, the fourth is on the console for control‑room convenience. There are dedicated talkback and listen mic inputs too, and each has SSL’s famous Listen Mic Compressor — these are patchable, so can be accessed on other channels (for example for drum processing). The talkback and listen mics can be operated from the console itself or, if you prefer, remotely.

Immersive Audio?

Although ostensibly a stereo console, the Oracle has been designed with immersive audio setups in mind, addressing two main challenges. For the channels/objects, there are several possible approaches. One, available now, is to integrate analogue processing into the immersive/object panning workflow, and this is achieved by ‘inserting’ the analogue signal path into the DAW’s channel signal flow, ie. DAW replay > DAW insert send > Oracle channel (input to direct out) > DAW insert return > object panner. This practice is adopted by some other systems.

For the monitoring, the immersive renderer is typically controllable from external digital signals. Oracle’s stereo analogue monitoring is also digitally controlled, and by switching the control protocols and message direction, the Oracle can switch from analogue stereo to digital immersive monitoring control. Professional immersive systems also manage the EQ and timing of their speaker sets, and where there is a common immersive/stereo L‑R front speaker pair (it’s not unusual for the immersive and L‑R speaker sets to be independent), one solution is to sum/switch the signal source of the L‑R monitors.

The control console is made up of three eight‑channel bays, the two on the left providing the inline channel controls — the bottom section might look rather familiar to users of the UF‑8 control surface!

The control console is made up of three eight‑channel bays, the two on the left providing the inline channel controls — the bottom section might look rather familiar to users of the UF‑8 control surface!

Knobs, Faders & Screens

So that’s what this thing can do with your audio, but the real benefit is in the way it’s all controlled. I have to say that I love the look and feel of the control surface, whose lower section’s three eight‑fader ‘bays’ should look instantly familiar to anyone who’s used SSL’s UF‑8 control surfaces. On the left and right of each bay are various buttons to bank and enact different control functions. Above and in alignment with the left pair of bays are the main inline channel controls, while above the third sit the centre‑section controls, along with a little empty space to accommodate your notebook, tablet and so on. Finally, above the lot is a meterbridge — or, more precisely, three wonderfully crisp and clear high‑resolution colour displays that by default serve as the meterbridge.

Each eight‑channel bay has its own screen. In the primary view, the default metering shows virtual bar meters in traditional SSL orange, which align with the physical channel controls. They also show other useful information such as track numbers and names and a numeric level readout. Similar meters on the third screen cater for the various busses, with the main mix’s meter on the left being taller than the rest. You can switch to another meter option, though: a set of virtual moving‑coil VUs. The idea, presumably, is to make users of yesteryear’s mixers feel more at home; personally I prefer the bars, though I might have liked the ability to change the colour. The screen has alternative Detail Views that allow you access to every parameter in the channel strip, even the fader, and display channel routing too. Further, smaller screens sit above the faders, again carrying useful context‑sensitive information.

The physical knobs you can see on the control surface might not be larger than traditional pots, but the LED rings around them, and the physical components beneath the panel, occupy more space, and this presents the console designer with a challenge: how many functions can you allow a dedicated control before it’s too difficult for the operator to reach everything? A decent balance has been struck here. There are go‑to single controls for most of the usual channel functions. Occasionally, you need to hit/hold a button before turning a control, but that’s as tricky as it gets. The knobs are touch‑sensitive on the side (the black surface being conductive carbon), so when you grab one the associated parameters appear instantly on the screen (whether that be the one at the top of the channel, or the smaller screen above the fader and pan pot). Other things are more discreetly indicated using the colour of the LEDs around the knobs. For instance, I mentioned above the ability to switch the EQ type, and each is treated to different colour LEDs. All this makes finding your way around pretty intuitive.

Perhaps the biggest practical departure from traditional analogue consoles for me was getting used to the same knob being used to adjust both the frequency and the bandwidth of the EQ. But I quickly got used to that, and I very much prefer this arrangement to the possible alternative of having more controls but having to switch between bands; there’d be greater potential there for big mistakes!

The screens also offer a more detailed view of the currently adjusted parameters. Here, on the centre section’s screen, you can see the graphical interface for the built‑in Bus+ compressor and dynamic EQ.

The screens also offer a more detailed view of the currently adjusted parameters. Here, on the centre section’s screen, you can see the graphical interface for the built‑in Bus+ compressor and dynamic EQ.

The centre section is operated in a similar way as the channels, though it arguably makes even better use of the screen, since there are more facilities to control, such as the Bus+ located here and the various monitor and foldback options. There’s both a large encoder for parameter adjustment and a large jogwheel for transport control. Since the encoder can be assigned to two parameters at once, you could, for example, adjust the Q and frequency of an EQ simultaneously. All in all, it works well — not ‘fussy’ in the way some digital control systems can seem.

Oracle strikes a superb balance between the speed and convenience of digital control, recall and automation, the sound of analogue electronics, and the direct hands‑on control of analogue consoles.

Right Here, Right Now!

Having begun this article by recounting the history of digitally controlled analogue consoles, what of the future? Development isn’t planned to end here, and I can see massive potential, particularly if SSL were to apply this digital control tech to, say, a multi‑channel dynamics processor. But already under development are various other features, including remote control of the Dolby Atmos Renderer software, and the implementation of more DAW plug‑in based control.

And in the here and now, just how good and relevant is the Oracle? Digital audio processing is capable of great things now, and not everyone is fanatical about analogue, but plenty of us appreciate its virtues, analogue consoles continue to be a real draw in high‑end studios, and some will always prefer the one‑knob‑per‑function layout of ‘real’ analogue desks. They’re increasingly impractical in today’s music industry, though, and the Oracle strikes a superb balance between the speed and convenience of digital control, recall and automation, the sound of analogue electronics, and the direct hands‑on control of analogue consoles. It’s such an elegant and intuitive implementation too.

At the time of writing there wasn’t yet a final published spec for the Oracle, but I’m told that, in terms of headroom, noise floor and distortion performance, the design target was to achieve similar technical performance to SSL’s Duality, AWS and ORIGIN consoles. And I’ve no reason to doubt that: it sounds great, gorgeously clean and detailed, like the other SSLs I’ve used over the last couple of decades. The preamps are versatile, and the familiar sound and control of SSL’s filter and four‑band EQ is reassuring. There are great processing options in the form of the Bus+ (which really is a lovely dynamics processor) and there are two LMC compressors too.

What this all adds up to is an enticing implementation of the digitally controlled analogue console concept. There’s absolutely space for something like this in today’s high‑end studios, even if I can only dream of buying and working on one! I hope the Oracle proves a success, as I’d love to see what else SSL might have up their sleeve.

Pros

- Big‑console capability in a relatively compact footprint.

- Recall is impressive: total, and near‑instant.

- O‑Control software facilitates standalone or DAW‑based automation.

- O‑Control can be used offline for efficient session prep.

- Excellent use of screens for metering and other visual feedback.

- Can be configured to suit different workflows.

- Switchable 4000 E and G EQ types.

- Built‑in Bus+ and LMC compressors.

- Doubles as a DAW controller.

- Huge future potential!

Cons

- As with the AWS, there’s no individual channel dynamics processing.

- Not inexpensive!

Summary

The concept of digitally controlled analogue mixers might not be entirely new, but it’s a long time since we’ve seen significant developments in this area. If you like working in the analogue domain but demand the convenience of digital, it doesn’t get better than this.

Information

24 inline channels £86,999. 48 channels £121,998. Prices exclude VAT.

Solid State Logic UK +44 (0)1865 842 300.

24 inline channels $149,999. 48 channels $199,999.

Solid State Logic USA +1 212 315 1111.