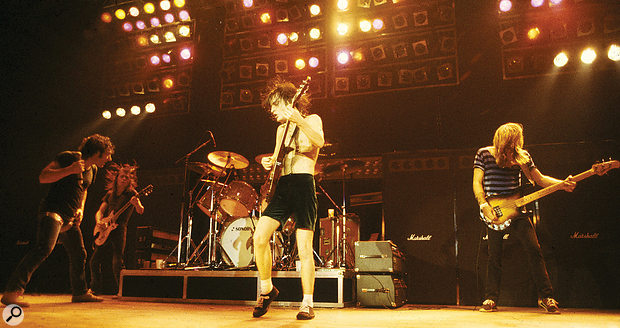

AC/DC performing a typically understated live show during the Back In Black tour.

AC/DC performing a typically understated live show during the Back In Black tour.

In 1980 AC/DC were on a roll and nothing — not even the death of their lead singer — was going to stop them.

In April 1980, just two months after lead singer Bon Scott’s death from a night of heavy drinking at a London club had prompted heavy metal pioneers AC/DC to consider disbanding, lead guitarist Angus Young, his rhythm guitarist brother Malcolm Young, bassist Cliff Williams and drummer Phil Rudd were back in the studio. Alongside them was Scott’s replacement, Brian Johnson, helping record a follow–up to the group’s breakthrough album, Highway To Hell. Titled Back In Black, AC/DC’s seventh studio LP took its name from the track that, penned as a tribute to the recently deceased frontman, featured Johnson’s defiantly upbeat lyrics in addition to an opening guitar riff that would help make the song one of the band’s signature tunes.

Johnson was recruited that March, Scott having previously sung his praises to Angus Young after watching him perform with Newcastle glam rockers Geordie. He stated in a 2009 Mojo magazine interview that his new bandmates told him the song’s words should be celebratory rather than morbid. This, in turn, prompted him to think, “Well, no pressure there, then.”

Welcome to Brian Johnson’s first project with AC/DC; taking over the spotlight from an iconic vocalist while performing numbers that certainly tested his own talents.

Highway To Highway To Hell

“Hitting some of those notes was a real challenge,” says Tony Platt who engineered Back In Black alongside producer Robert John ‘Mutt’ Lange after having mixed Highway To Hell and overdubbed a Scott vocal. “There was a massive amount of pressure on Brian’s shoulders, but everyone was very sympathetic and supportive of him. We were all completely in awe of what he was doing and there were lots of positive vibes. So, whenever he had a moment of ‘I’m not sure I can do this,’ there were plenty of people around to tell him quite clearly that he could.

“Recording a band like AC/DC, the main thing I had to do was avoid screwing up. They were constantly providing the goods and I therefore had to be there to catch them at the right moment. Well, that was even more important with regard to Brian, because if I didn’t capture some of his performances the first time around it would have been a really steep climb for him to get back to that same place. Those vocals were absolutely incredible and what he achieved was quite extraordinary. He and Bon were totally different types of singer. Whereas Bon’s voice was extremely quirky, Brian’s was sheer power.”

The producer and/or engineer of anyone from Bob Marley, Toots & the Maytals, Aswad and Jazz Jamaica All Stars to Free, Iron Maiden, Motörhead, the Cult, Cheap Trick and Buddy Guy, Tony Platt moved from the Yorkshire town of Barnsley to the Oxfordshire town of Henley–on–Thames when he was seven–years–old and secured his first job as a tea boy and makeshift tape machine operator at Central London’s independent Trident Studios in 1969. Six months later, he then became a fully fledged tape op at Basing Street Studios, owned by Island Records founder Chris Blackwell.

Tony Platt in 1980.“Being there was like having died and gone to Heaven,” he says. “Most of my record collection was made up of albums on the Island label by artists such as Free, John Martyn and Jethro Tull, and there was an unwritten rule that, if an engineer didn’t make it to a session on which you were the tape operator, you had to step in for him. Luckily, I had eight months to watch what was going on before that happened to me, but I still say that getting the job was the easy part whereas hanging on it to was the more difficult one. It was all about learning as quickly as I could before taking advantage of the opportunities that came my way.”

Tony Platt in 1980.“Being there was like having died and gone to Heaven,” he says. “Most of my record collection was made up of albums on the Island label by artists such as Free, John Martyn and Jethro Tull, and there was an unwritten rule that, if an engineer didn’t make it to a session on which you were the tape operator, you had to step in for him. Luckily, I had eight months to watch what was going on before that happened to me, but I still say that getting the job was the easy part whereas hanging on it to was the more difficult one. It was all about learning as quickly as I could before taking advantage of the opportunities that came my way.”

These included assisting on 1971 sessions for Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, Traffic, the Who, Paul McCartney and Jethro Tull. That same year, Platt engineered a record by Spooky Tooth guitarist Luther Grosvenor, as well as a New Age album by Henry Wolff and Nancy Hennings that was the first to feature singing bowls and Tibetan bells. Soon the engineering credits were gathering pace with Toots & the Maytals’ Funky Kingston, the Wailers’ Catch A Fire and Burnin’ and Sparks’ Kimono My House before Platt went freelance in 1974.

A couple of years later, he made his debut as a producer on Aswad’s self–titled first album, and thereafter he also served as chief engineer at a West Sussex studio named Pebble Beach Sound Recorders for his best friend, guitarist–producer Adam Sieff. Here he recorded demos for the Stranglers and Thin Lizzy while also working with UK reggae artists the Cimarons.

“After I left Pebble Beach, I spent about 10 months running the fantastic Eastlake/Westlake–designed Stone Castle Studios in Carimate, Italy, just north of Milan,” Platt recalls. “Then, when I returned to England, Adam Sieff introduced me to Mutt Lange. He had been producing AC/DC’s Highway To Hell at London’s Roundhouse Studios with Mark Dearnley engineering, and wanted to have it mixed by someone who could give it the vintage British Free–type rock sound. The mix took place at Island’s Basing Street Studios where I also recorded a few overdubs: some backing vocals on ‘Highway To Hell’ and the lead vocal on ‘Night Prowler’.

“We had to do a few things to get the sound the way Mutt was hearing it. Roundhouse was a very dead studio and he wanted to have it sound like everything was played in the same room at the same time. As there wasn’t a lot of ambience, I had to feed stuff out through speakers in the room at Island [Basing Street] to give it ambience and a sense of space. A lot of the guitars on the recording were very separated, there wasn’t a lot of leakage and there were quite a few overdubs. So, I also stated very clearly, ‘The next time you record, guys, the best thing to do is record some ambience along the way and try to do it all in one room.’”

It was during the afternoon of 19th February 1980, while Mutt Lange and Tony Platt were working together at London’s Battery Studios on an album by a band named Broken Home, that Lange received a phone call informing him Bon Scott had passed away.

The MCI desk at Compass Point.“We were both in a state of shock,” Platt recalls. “Then, over a very short period of time, the band decided to carry on and the search for a new singer began. I was staying with a friend in Kensington while doing the Broken Home album, and every day, when Mutt picked me up in his car on the way to the studio, he’d have a cassette recording that Malcolm and Angus had sent him from the previous day’s auditions in order to get his feedback. It didn’t take them long, however, to pick Brian Johnson.”

The MCI desk at Compass Point.“We were both in a state of shock,” Platt recalls. “Then, over a very short period of time, the band decided to carry on and the search for a new singer began. I was staying with a friend in Kensington while doing the Broken Home album, and every day, when Mutt picked me up in his car on the way to the studio, he’d have a cassette recording that Malcolm and Angus had sent him from the previous day’s auditions in order to get his feedback. It didn’t take them long, however, to pick Brian Johnson.”

Compass Point

That April, when the sessions for Back In Black were about to commence at Chris Blackwell’s Compass Point Studios in Nassau, there was a slight delay due to AC/DC’s equipment briefly being held by customs while a hurricane messed with the facility’s electrical system which, being on a Caribbean island, was already erratic. Still, none of this prevented Tony Platt from making the necessary preparations.

“Compass Point was a wonderful place,” he asserts. “Everything about it pointed towards music. We were in a part of the world where music was a part of everybody’s life, so the studio staff there were great. We were all there for the same reason, there was a terrific camaraderie, and often the biggest problem we’d have was getting people in off the beach when it was time to record.

“The studio itself was fairly dead–sounding with quite a low ceiling. So, I took a bit of time working out how to set everybody up, wandering around while hitting a snare drum. There was one place where the snare sounded a lot louder and much fuller than everywhere else — which, I later discovered, was because of space above the ceiling there — and that’s where we set up the drum kit before positioning the guitars around it.”

Looking through the control room window towards the live area, the producer and engineer saw the band members in largely the same format as they used on stage. While Phil Rudd’s drums were in the sweet spot that Platt had discovered (halfway back in the room, slightly left of centre) Malcolm Young’s guitar rig was screened off nearer the window and further to the left; his brother’s was screened off to the right; and Cliff Williams, standing next to the drums, had his bass rig inside a tiny area that, according to the engineer, “people laughingly referred to as the vocal booth... As there weren’t any guide vocals, Brian just hung around in the control room.”

Modelled on Basing Street, the Compass Point control room was equipped with a 48–channel MCI console, 24–track MCI tape machine and monitors comprising Tannoy Red drivers inside Lockwood cabinets, as well as a then–standard array of outboard gear and good selection of microphones.

That Guitar Sound

“The miking of the guitars changed for each song,” Platt explains. “We had a number of different Marshall heads and cabinets, and we used a different combination on each song. Sometimes it would be a 50 Watt head and the appropriate cabinet, sometimes it would be a 100 Watt head, and there were a couple of different 100 Watt heads that had their own textures. Generally speaking, we only ever turned up the amplifiers as far as we needed to — it wasn’t a matter of starting on 11 and then turning them down. We’d turn them up until the cabinets were biting the right amount and the space around the cabinets was lighting up in the right way. Of course, the timbre of the amps would change according to the chords being played. So, while the guitars were each recorded with either a couple of Neumann U67 microphones or a U67 and U87 — sometimes cardioid, sometimes figure of eight, sometimes omni, placed on different speakers of the cabinet — I would move them around depending on the combination of amps being used for songs that were recorded as individual pieces. As such, I’d never do these things the same way twice.

“I know this is of great interest to a lot of people, but it honestly wouldn’t make the slightest bit of difference if somebody recreated the exact same combination. There have been so many times when people have asked me to get them a sound like Angus, and I’ve generally said, ‘We’ll need a Marshall head, we’ll need a Marshall 4x12, we’ll need a Gibson SG and we’ll need Angus. Without them we just won’t have the right combination.’ Then again, the guitars would also change from song to song based on the ones that the players were feeling most comfortable with. As we’d start to zone in on the sound, those players would respond to what they were hearing by playing better. As they played better, the sound would improve, and this might prompt me to change the mic positions a little bit; moving them in or out to advance the sound in small increments. Meanwhile, Mutt would be listening to the song and discussing the arrangement with the guys, making changes that would also impact the sound.

Tony Platt today.“It was like organising a photographic set, where the photographer keeps making small adjustments to the lighting and the way that the subject is posing until, at a certain point, he clicks the shutter and says, ‘That’s the photo I want’. It’s exactly the same recording a track: at a certain point you go click — now we’ve captured the sound, the performance and the right arrangement. The starting points are relevant in that respect, but the fine tuning is always going to be totally different every time you visit it. In other words, even with the same guys, same process and same gear in the same studio today it would be different.

Tony Platt today.“It was like organising a photographic set, where the photographer keeps making small adjustments to the lighting and the way that the subject is posing until, at a certain point, he clicks the shutter and says, ‘That’s the photo I want’. It’s exactly the same recording a track: at a certain point you go click — now we’ve captured the sound, the performance and the right arrangement. The starting points are relevant in that respect, but the fine tuning is always going to be totally different every time you visit it. In other words, even with the same guys, same process and same gear in the same studio today it would be different.

“Angus used a radio transmitter when doing the solos. His guitar was the only overdub and he would then play rhythm after the solo, all the way to the end so the dynamics didn’t drop. However, the sound that his radio transmitter gave the guitar was quite different. In fact, unhappy with the solo on ‘Shoot To Thrill’, he replaced it when we were at Electric Lady to do the mix and, as we didn’t have the radios with us, I had a lot of trouble matching the sound.

“When it came to the drums, I miked them with two U87 overheads, a U47 and/or an AKG D20 on the bass drum, an AKG 414 on the hi–hat and a Neumann KM86 on the snare with a Shure SM57 underneath. The miking of the tom–toms — if we were using them — depended on their role. Sennheiser MD421s got used quite a bit, but sometimes I might even put 87s on the tom–toms if I wanted them to be very specific. In the room there were at least a couple of ambience microphones, including a Neumann stereo mic which I moved around sometimes over the top of the drums and sometimes more towards the guitars. Meanwhile, the bass guitar was recorded with a D20 and possibly a 414 on the Ampeg Portaflex amp along with a DI.”

Vocal Debut

The Young brothers composed all of the music for Back In Black while, in the tradition of Bon Scott, Brian Johnson penned his own lyrics.

“AC/DC went about their songwriting in a very particular way,” says Tony Platt. “Angus and Malcolm put the riffs together and the songs were already in pretty reasonable shape by the time we entered the studio, even though the lyrics still needed to be written. In fact, most of the numbers had titles that ended up being used. At the same time, the songs on Back In Black all had backing tracks consisting of two guitars, bass and drums, recorded in complete takes with some edits. Editing has always been one of my strong points. So, if we had a couple of takes that sounded like they might go together well, I’d do a rough mix and test edit on quarter–inch tape. Then, if everybody was happy with the result, I’d do the same on the two–inch.”

After all of the backing tracks had been recorded, it was time for Brian Johnson to make his AC/DC debut. Accordingly, the studio was cleared and he then stood at the back of the live area to perform his vocals.

“We put screens around Brian as he wanted to have some privacy and didn’t like the idea of everybody staring at him,” Platt recalls. “He also didn’t want the air–conditioning to be too cold after he’d warmed up his voice. So, once he went in to record a vocal he had to stay there, because returning to the control room would have meant a change of temperature and humidity that wouldn’t have been at all good for his voice. This meant getting as much out of him while he was in there, captured with a U87 to handle the power of his voice.

“A reasonable amount of comping was done with Brian’s vocals, but not a vast amount. I learned so much from Mutt in that regard, including how you try to get three or four performances that would be perfectly acceptable as a master vocal and then compile the best of the best, taking things to a higher level every time.”

Mixing & Mastering

With Johnson’s performances all committed to tape, Mutt Lange, Malcolm Young and Cliff Williams then took care of the backing vocals, including a few that were overdubbed during the mix. This took place at New York’s Electric Lady in May of 1980 as Tony Platt far preferred the idea of using the Neve 8078 console there than Compass Point’s MCI.

“It was always difficult to find a studio where Mutt liked the monitors,” he explains. “I hadn’t worked at Electric Lady before, but I’d always been quite a fan of Westlake rooms and the one in Studio A was really good. I’m not crazy about horn–loaded monitors, but something about the way Westlake rooms were balanced really appealed to me. Eastlake rooms were largely about dampening everything down and controlling the sound as much as possible, whereas Westlake tuned the room to its characteristics. You weren’t trying to make the room do something it didn’t want to do. You were actually taking its good attributes and enabling them to be the most prominent ones.

“The mix for me always starts when the song is written. Moving the sound and performance towards a certain point means that you’re suggesting how the mix is going to be, and the idea really is to give yourself a recording that will enable you to be creative when it’s time to mix while providing you with as many options as possible. For Back In Black it was a very straightforward process. A lot of it was about getting the right blend, and there were some bits and pieces that we knew we’d want to introduce; like the slight detuning underneath the snare. The thing with AC/DC was that they didn’t like to hear any effects, so we had to be very, very careful with reverbs, delays and anything like that. We’d introduce them just to do the job they needed to do without letting them stand out or using them as an effect in — rather than a contribution to — the mix.”

“The mix for me always starts when the song is written. Moving the sound and performance towards a certain point means that you’re suggesting how the mix is going to be, and the idea really is to give yourself a recording that will enable you to be creative when it’s time to mix while providing you with as many options as possible. For Back In Black it was a very straightforward process. A lot of it was about getting the right blend, and there were some bits and pieces that we knew we’d want to introduce; like the slight detuning underneath the snare. The thing with AC/DC was that they didn’t like to hear any effects, so we had to be very, very careful with reverbs, delays and anything like that. We’d introduce them just to do the job they needed to do without letting them stand out or using them as an effect in — rather than a contribution to — the mix.”

Maintaining quality control, both Tony Platt — who would also engineer AC/DC’s 1983 album Flick Of The Switch — and Mutt Lange were involved in the Back In Black mastering by Bob Ludwig at Masterdisk in New York. They then checked the test pressings before the record was released on 25th July 1980. This would go on to sell more than 50 million copies worldwide while becoming the second-highest–selling album of all time after Michael Jackson’s Thriller. Peaking at number four in the US, it topped the charts in the UK while spawning four singles: ‘You Shook Me All Night Long’, which was a Top 40 hit on both sides of the Atlantic; the aforementioned ‘Hells Bells’; the title track, which went Top 40 in America; and ‘Rock & Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution’, which climbed to number 15 in the UK.

Birds In The Belfry

‘Hells Bells’, the opening track on AC/DC’s first album without Bon Scott, commences with the slow, funereal–sounding tolling of a 2000–pound bronze bell. Manufactured by John Taylor Bellfounders in the Leicestershire town of Loughborough, this was recorded by Tony Platt using Ronnie Laine’s mobile studio following the completion of the Back In Black tracking sessions at Compass Point in the Bahamas.

“The bell that AC/DC had ordered to take out on tour with them still hadn’t come out of the mould when I arrived in Loughborough,” Platt recalls. “So, the people who were making it arranged for me to record another bell of the same size and key that was hanging in a nearby church. However, after placing microphones in the belfry I discovered that what no one had considered were the birds living inside there. As soon as the bell was hit, the first thing we’d hear was this mad fluttering of wings as pigeons flew away. Then, by the time the bell stopped ringing enough for us to hit it again, all of the birds had returned. We therefore had to abort that whole idea while the bell foundry people hurried up the process of getting the other bell out of the mold.

“As I couldn’t get the Rolling Stones’ mobile, I used Ronnie Laine’s mobile, which was in an Airstream caravan. At that time it was being run by a mate of mine, so we towed it up to Loughborough and actually parked it inside the bell foundry. The bell itself weighed one ton because that was the largest feasible size to take on tour, but the pitch of the bell as you hear it on the record is an octave lower than the actual bell; it was slowed down to half–speed to replicate the sound of a two–ton bell that would have been impossible for the band to take on the road with them or to hang in the venues. As a result, when that bell was hit on stage, it was an octave higher than on the record.

“The guy who made the bell was the guy who hit the bell on the record. We hung it on a block and tackle in the foundry and there was a specific spot, painted red, where he had to hit it. Being that I had a short time in which to record this before flying to New York to do the mix, I put up 15 or 16 microphones all around in different places, and recorded across 24 tracks using lots of Neumann U87s and some AKG 451s. As a bell’s sound is mostly harmonic, it’s very difficult to record. So, I went all the way from having Shure SM57s at the dynamic end to using B&Ks at the top end, covering all the bases. That was the only way to do it because I had to consider what we were going to mix and slow it down to half–speed. When you do that, all sorts of things you didn’t know were there suddenly appear.

“At Electric Lady when we were doing the mix, Mutt and I chose a combination of the close and distant microphones that produced the best sound, made a mix to half–inch at 30ips and then slowed that down to 15ips. Out of the takes that we had, we chose the best one and, because there were no samplers in those days, spun it in. We had quarter–inch and two–inch tape machines, I started the two–inch and dropped it in, and Mutt started the quarter–inch at the appropriate moment.”