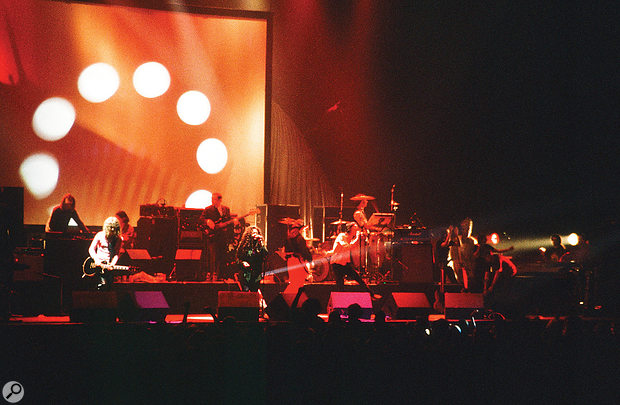

Primal Scream playing a benefit concert for miners in Sheffield, 1992. Photo: Grant Fleming

Primal Scream playing a benefit concert for miners in Sheffield, 1992. Photo: Grant Fleming

With the Screamadelica album Primal Scream didn’t just reinvent themselves as a band, they reinvented what it meant to be a band.

By the end of the 1980s, it looked like Primal Scream were finished. Having formed in Glasgow in 1984, their eponymous and hard-rocking but unspectacular second album had been released in 1989 to poor sales and general indifference. “It felt like we were fucked,” singer Bobby Gillespie admitted to this writer in 2008. “Then we started to go to acid house clubs in long hair and leather, initially because of the drugs. We were taking speed and then we started taking E and really loved it. We’d given up on contemporary rock music. We were more into contemporary electronic dance music. So we had the idea that we wanted to make songs that they would play in the clubs.”

With this notion in their minds, the group handed over the tapes of one song from the Primal Scream album to first-time remixer, DJ Andrew Weatherall. At first, tentatively, Weatherall just toughened up the beats of the Stones-y rocker ‘I’m Losing More Than I’ll Ever Have’. Going into the studio to hear the result, Primal Scream guitarist Andrew Innes thought Weatherall could go much further with the track, instructing him to “forget what we’ve done. Just fucking destroy it.”

Built around the original song’s slide guitar/bongo breakdowns and its storming, horn-powered outro, the remix, entitled ‘Loaded’, was a dance floor-ready track which entirely turned around the fortunes of Primal Scream. Andrew Weatherall first got the sense that ‘Loaded’ was set to become a big record when he played it during his set at West London club Subterrania in 1990 and it instantly fired up the crowd. At 4am, Weatherall called Gillespie at his home in Brighton to say, “Fucking hell, man, everybody’s going mental for the record.”

‘Loaded’ was a Top 20 hit in February 1990 and Primal Scream immediately set to work on a follow-up single. The track, ‘Come Together’, was to cement a new way of working for them: creating tracks in the knowledge that they would be handed over to remixers. Still, the recording of the song got off to a bad start. “We went in to record ‘Come Together’ and it was a bit of a disaster,” remembered Gillespie. “The drummer turned up with some fucking [horse tranquiliser] drug that Keith Moon overdosed on. We all took it and collapsed.”

When in better shape, the band recorded a version of the beats-driven, ’60s-echoing pop track which was then remixed for single release by DJ Terry Farley in a traditional song-based form with Bobby Gillespie’s vocal running all the way through it. But, encapsulating the spirit of Screamadelica, the album it was to become the centrepiece of, the version of ‘Come Together’ that was to become best known was an extended 10-minute remix by Andrew Weatherall and Hugo Nicolson. The track ditched Gillespie’s voice and brought the song’s gospel backing vocalists to the fore, mixing them with an impassioned speech about music and togetherness by Jesse Jackson from the Wattstax concert in Los Angeles in 1972.

The result was a dance floor anthem that was to capture the saucer-eyed spirit of the early ’90s.

Mixing & Remixing

Hugo Nicolson began his recording career in the ’80s as a tape op at The Townhouse, Olympic and The Manor, observing the likes of Scritti Politti and Tears For Fears at work. “I worked my arse off and I only got paid two pounds an hour,” he remembers. “But I was loaded. I didn’t have to buy any groceries, ’cause they fed me. I felt like I was very rich even though I was getting two pounds an hour.”

Nicolson quickly progressed to engineering two albums for Julian Cope, 1988’s My Nation Underground and its 1990 successor Skellington, which was recorded and mixed in two days. It was to inspire his swift and spontaneous approach when it later came to working with Primal Scream.

“I love Skellington and it was such a good time,” Nicolson enthuses. “We were brought in to do some Teardrop Explodes remixes but none of it was done to a click. I said, ‘This is gonna be impossible, we’ve got to put everything in time to the sequencer.’ He was basically looking for an excuse not to do it. He said, ‘OK, well we’ll just record something else’ and he went in there and bashed out about 12 songs with his acoustic guitar and vocals.

“Then we sat down and had a cup of tea, and he said, ‘Can we do overdubs on that?’ I said, ‘Well, it’s on a DAT at the moment’, and so I just copied it onto a multitrack. We then did overdubs and mixed it on the last day and that was it. It was such a good time, and it was so short and sweet and no stress. It has a great place in my memory.”

Hugo Nicolson first teamed up with Andrew Weatherall that same year to work on a procession of remixes which had been offered to the latter in the wake of the success of ‘Loaded’, including tracks for My Bloody Valentine, James and That Petrol Emotion.

Primal Scream backstage at a gig in Kawasaki. Hugo Nicolson is in the middle at the back. Nicolson’s approach to remixes was very much inspired by his time working on and off in the previous two years with On-U Sound’s Adrian Sherwood, particularly the latter’s dub techniques. “I saw how he just played the desk,” says Nicolson. “So I just looped everything all the way through with no arrangement or anything, and then I’d just arrange by muting and cutting and putting effects on things on the desk.” Automation on the SSL helped immensely. “I could do one thing,” he remembers, “and then go back and do another, and gradually create this kind of collage of music.”

Primal Scream backstage at a gig in Kawasaki. Hugo Nicolson is in the middle at the back. Nicolson’s approach to remixes was very much inspired by his time working on and off in the previous two years with On-U Sound’s Adrian Sherwood, particularly the latter’s dub techniques. “I saw how he just played the desk,” says Nicolson. “So I just looped everything all the way through with no arrangement or anything, and then I’d just arrange by muting and cutting and putting effects on things on the desk.” Automation on the SSL helped immensely. “I could do one thing,” he remembers, “and then go back and do another, and gradually create this kind of collage of music.”

‘Come Together’

The day Weatherall and Nicolson entered the studio to remix ‘Come Together’ was considered by the latter just to be another job. The pair’s routine was to start and complete a remix over two days, working in the now-defunct Eden Studios in Chiswick. Primal Scream had worked on the song on a four-track at Andrew Innes’s house in the Isle Of Dogs, before booking time at Jam Studios in Crouch End to record the vocal version of ‘Come Together’ with the gospel backing singers.

“It was the first time we had a budget to work with,” Bobby Gillespie remembered in the liner notes of the 2015 reissue of Screamadelica. “Because we had a hit record, we knew we would be indulged. So we got a choir in. We were suddenly able to use our imagination and say, ‘Let’s try some gospel singers in here.’ Then we double-tracked it and put harmonies on it so it sounded like a lot more. It was a fascinating process. We thought we were Mozart: ‘I’ve got another idea, try this.’”

By the time Weatherall and Nicolson got the tape for ‘Come Together’, they were pleased to discover that Terry Farley and his partner Pete Heller had cut all of the band’s performances in time to a click track. “So they saved me a couple of days work,” says Nicolson, “having to be very bored trying to figure out how to put everything in time with the sequencers.”

As was typical in the early ’90s, the sequencing setup was based around an Atari 1040 ST computer running C-Lab Notator, MIDI-triggering a bank of Akai S1000 samplers and a Korg M1 synth. Additionally, on a recent trip to Japan, Nicolson had bought himself an Akai MPC60 sequencer-sampler that was to prove central to the beats on ‘Come Together’, not least because when he worked with US producer Jeff Lorber on sessions for UK boy band Brother Beyond in 1989, he had managed to come away with a library of drum samples.

“There was this timbale that I used on every single remix, which became a bit of signature,” Nicolson remembers. “I had all these pretty cool samples to use. They weren’t just 909 and 808. I had quite a good library, so the MPC was really helping me with a good base of sounds to work with.”

But, as still something of a novice when it came to programming (his skills being in engineering until 1990), Nicolson was slightly nervous when Andrew Weatherall asked him to come up with the beats for ‘Come Together’. “I was in panic mode most of the time during this process going, ‘How am I gonna get away with this?’” he laughs. “If anything good happened, it was a relief. Andy would bring in references [on vinyl] and he’d go, ‘This is good, it seems to work when I’m DJing.’ So he was guiding the production that way and I would implement the things that he thought were good.

“For ‘Come Together’, he brought in a beat and he said, ‘I really like this.’ I was like, ‘Oh God, do a beat?’ I’m a crap drummer. So I knocked together that beat on my MPC60. And it was not sounding very good, and I’m like, ‘Oh shit, what am I gonna do now?’”

Thinking on his feet, Nicolson plugged up an AMS DMX 15-80S delay, set to an eighth and a 3/16th, and added them to the beat he’d programmed. “So it had this kind of shuffly movement going on in the background,” he says, “and suddenly the beat sounded a lot better. Back then there was a lot of shuffle going on in the grooves. So I was using my engineering skills to kind of make up for my musical ineptness. The congas in ‘Come Together’ were these funny little bad-sounding bongos and I basically squeezed as much bongo-ness out of them as I could with a Bell [Electrolabs] flanger. That was another bit of gear that I loved.”

Hugo Nicolson manning the samplers (and tambourine) at the Feile Festival. From here, the pair began building up the track, working through the arrangement and mixing down the parts to tape as they progressed through the song. “We did everything in edit sections,” says Nicolson. “There was a master tape with all their stuff they’d recorded, and then I would run all the sequencers live alongside the tape.

Hugo Nicolson manning the samplers (and tambourine) at the Feile Festival. From here, the pair began building up the track, working through the arrangement and mixing down the parts to tape as they progressed through the song. “We did everything in edit sections,” says Nicolson. “There was a master tape with all their stuff they’d recorded, and then I would run all the sequencers live alongside the tape.

“I started playing a little piano part using an S1000 sample. Then I found this cartoon skid sound I’d sampled, and I turned that backwards and started playing with that. That’s the weird kind of ‘weee-weee’ sound that goes all the way through. There were some funny psychedelic noises which were samples that Andy had, the kind of intro ‘whoop whoop whoop’ noise. Then I played a bass line on the M1. On the first half of the remix, there’s a bit of a dodgy note in the bass because as I say I wasn’t the best musician. So if you listen carefully you can hear it.

“I got all that together and then the computer crashed. And I was so involved in what I was doing that I hadn’t saved it. So I had to replay everything in. But what was great was I replayed the bass with the right note, so from when the gospel vocals come in, the bass line is correct.”

Adding the Jesse Jackson speech samples gave ‘Come Together’ a focal point to replace Bobby Gillespie’s vocals, while the AMS delay Nicolson had patched in for the MPC60 beats came into greater play later in the track. “I’d put the AMS delay on the stereo aux send,” he remembers, “and there’s a function on the SSL, quad to cues, which basically sends everything to the left/right auxiliaries on the desk. It got to the big bit where I dropped down and the gospel vocals came in and I thought, OK, I need to kind of make that a bit more spacey. So I just hit quad to cues, and suddenly all the mix was going to the delays and it got a lot dreamier. I might unswitch every now and again to kind of clear it up, but the whole mix is kind of floating around in crazy delays.”

In keeping with Primal Scream’s high-living modus operandi at the time, when the band arrived on the second day to hear Weatherall and Nicolson’s work on ‘Come Together’, an impromptu party broke out in the lounge at Eden Studios. “Andy and the band were partying most of the way through that remix,” Nicolson laughs. “Andy would pop his head in, go, ‘Sounds great, sounds great’, and then pop back to the party. What was great about Andy for me was he was really encouraging, ‘cause I’d have my doubts as to whether something was good. It just gave you confidence to do more. He was definitely building my confidence all the way through those mixes.”

Screamadelica

At the time, there was no firm plan for the album that was to become Screamadelica, with the scheme being just to release a series of singles. The follow-up single to ‘Come Together’ was Primal Scream’s ballad-paced and hypnotic ‘Higher Than The Sun’ (produced by the Orb), which Weatherall and Nicolson remixed in a highly ambitious seven-minute version subtitled ‘A Dub Symphony In Two Parts’, the second half featuring a rolling bass line from Jah Wobble. Both versions of ‘Higher Than The Sun’ were to make the tracklist of Screamadelica.

“They were all remixes not intended for an album, I felt, right from the very beginning,” says Nicolson. “Our attitude was, Let’s fuck this up. Let’s make this unrecognisable from what it came from. That was my goal, to make it a completely different thing that had its own life.

“With ‘Higher Than The Sun’, I was in Olympic Studio 2 with Andy and we were messing around. We got to the end of the song and it was like, ‘What are we gonna do now?’ Andy said, ‘Well, Wobble always says he’ll do anything for me.’ So he gave him a ring and Wobble came down and did the bass, and then we had the second half. That was the first time that Andy had actually got involved in moving any faders on the desk. We did this little drum break where we were kind of to-ing and fro-ing. I was at one part of the desk cutting things in and out and he was at the other side of the desk cutting things in and out.”

The next track Weatherall and Nicolson worked on was the trippy house pulse of ‘Don’t Fight It, Feel It’. Primal Scream were now operating out of their own basic studio in Hackney, East London, where they would program tracks and record vocals, typically after-hours. “[Andrew] Innes got a sampler,” Gillespie recalled to me, “and we started writing songs on piano to loops rather than jamming as a rock band. ‘Don’t Fight It, Feel It’ was written at six in the morning, still up on an E, listening to Northern Soul and thinking, ‘Let’s write a song like that, except modern.’”

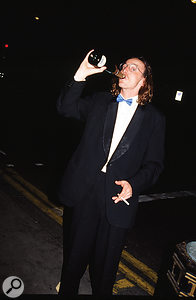

Hugo Nicolson celebrating after Primal Scream won the inaugural Mercury Music Prize for Screamadelica in 1992. When Weatherall and Nicolson got their hands on the track, fronted by singer Denise Johnson rather than Gillespie, they spent a day-and-a-half on it, but weren’t overly happy with the results. “I was like, OK, it’s not bad,” says Nicolson. “We got it finished, and we probably had two or three hours left and he said, ‘Let’s maybe just do another one quickly.’ I was like, Oh great, how am I gonna make another one in two or three hours?

Hugo Nicolson celebrating after Primal Scream won the inaugural Mercury Music Prize for Screamadelica in 1992. When Weatherall and Nicolson got their hands on the track, fronted by singer Denise Johnson rather than Gillespie, they spent a day-and-a-half on it, but weren’t overly happy with the results. “I was like, OK, it’s not bad,” says Nicolson. “We got it finished, and we probably had two or three hours left and he said, ‘Let’s maybe just do another one quickly.’ I was like, Oh great, how am I gonna make another one in two or three hours?

“But that day I had listened to some remix on the radio that had a vocal sample that they’d gated. I remembered the rhythm of the gate, and I thought, OK, I’m just gonna gate absolutely everything. So I got my MPC and I made that rhythm to send to all the gates. I put the gates over the drums, over the guitars. I’d have them so I could switch them in and out on certain channels. But pretty much everything was going through them and that’s how that came together so quickly basically. It was suddenly like, OK, that’s interesting.”

Adding to the hallucinatory quality of the dance track, Nicolson then reversed the bass line in the S1000. “There was a lot going on and I didn’t think I’d have time to figure out how to play a bass line. I was messing around with it, going, Everything sounds lame. So I started listening to the bass seeing if I could use that and then I heard this boom-boom-boom fill, and I thought, Oh I wonder if I get that and maybe turn it backwards in the sampler... I spent a little while trying to get the timing of that to work.”

Next came the odd whistling hook which runs throughout the track. “The whistle was funny,” Nicolson laughs. “Andy goes, ‘OK we need a whistle.’ There was one in the M1 and so I just played that funny little thing which went all the way through the song.”

Turning to Denise Johnson’s vocal tracks, Nicolson thought they could benefit from sounding as if they were coming down a phone line. “I wasn’t involved in the recording of them,” he says. “But I basically just did a kind of a telephone voice and made her amazing voice sound as tiny as possible. It kinda sounded cool to me doing that. Adrian Sherwood used to do that kind of stuff all the time, and my main guidance through all of this time was, What would Adrian do? I just filtered off the top and bottom and then added a whole load of 2k.”

The other Weatherall/Nicolson tracks that were to appear on Screamadelica — ‘Inner Flight’, ‘I’m Comin’ Down’, ‘Shine Like Stars’ — followed very quickly. Especially now that the band themselves were highly productive when it came to their own programming and ideas for soundscapes. “It was a real time for experimenting,” remembered Andrew Innes, “because the technology changed with samplers. So we could decide, we’ll have a sitar or we’ll have a flute. You didn’t have to hire a flute player and try and tell him what to play. It was great, the freedom.”

The track that featured flute as a prime instrument was the Pet Sounds-inspired electronic fantasia ‘Inner Flight’. “It was a very bad flute sample,” recalls Nicolson. “I remember Andrew Innes commenting on it, congratulating me on doing something good with that. I did a lot arranging with funny little drums on that one. I’d do these really percussion fills, kind of like ‘boop boop.’ Just little things to egg the next section on.”

Primal Scream on stage in Kawasaki. Hugo Nicolson far left. In marked contrast, Primal Scream recorded two band-based tracks, ‘Movin’ On Up’ and ‘Damaged’ with the Rolling Stones’ former producer Jimmy Miller. Finally, the 64-minute long Screamadelica was complete. “Andrew sequenced it and we got the sleeve together,” said Bobby Gillespie. “It was a proper double album in the gatefold sleeve and we were just really proud of it. We went, Y’know what? We’ve finally made a good record that we can be proud of.

Primal Scream on stage in Kawasaki. Hugo Nicolson far left. In marked contrast, Primal Scream recorded two band-based tracks, ‘Movin’ On Up’ and ‘Damaged’ with the Rolling Stones’ former producer Jimmy Miller. Finally, the 64-minute long Screamadelica was complete. “Andrew sequenced it and we got the sleeve together,” said Bobby Gillespie. “It was a proper double album in the gatefold sleeve and we were just really proud of it. We went, Y’know what? We’ve finally made a good record that we can be proud of.

“I do remember thinking it was like an underground record. Although ‘Loaded’ and ‘Come Together’ had been hits, the singles after that — ‘Higher Than The Sun’, ‘Don’t Fight It, Feel It’ — hadn’t been hits. I remember thinking it could be like Tago Mago by Can — a really cool underground record that people might like in 30 years’ time.”

Highs & Lows

Instead, upon its release in September 1991, Screamadelica helped to define its era, particularly since Primal Scream’s live performances were now less like rock gigs and more like raves. Hugo Nicolson was asked to join the band to control the programmed elements of the sound from the stage. “I was basically running all the MIDI gear and then I would just dub everything up,” he explains. “I’d be basically hitting play on a drum machine and then doing my best dub job.”

But joining the Primal Scream circus took its toll on Nicolson. “Yeah it was full of incidents,” he laughs. “I acclimatised amazing quickly. The first day was insane, the first week was insane, but then it becomes normal. It was more kind of punk rock than The Second Summer Of Love. I was trying to keep up with them.”

When Nicolson was on tour with the band in Australia and in a worryingly altered state, finding himself looking for the ‘steering wheel’ of the Sydney Opera House, he knew he was in trouble. “I overtook something and had to jump ship,” he says. “I checked myself into hospital and left. I couldn’t go back."

When Nicolson was on tour with the band in Australia and in a worryingly altered state, finding himself looking for the ‘steering wheel’ of the Sydney Opera House, he knew he was in trouble. “I overtook something and had to jump ship,” he says. “I checked myself into hospital and left. I couldn’t go back."

However, Nicolson did work with Primal Scream again in the studio on the track ‘Insect Royalty’ from their 2000 album XTRMNTR. But after acting as the recording engineer on Radiohead’s In Rainbows in 2007, he relocated to Los Angeles where he’s since divided his time between working with the likes of Father John Misty and Beck and on soundtracks for films including Hunger and Ouija.

Postscript

Twenty years after the release of ‘Come Together’, in 2010, Primal Scream revived Screamadelica for two shows at London’s 10,000 capacity Olympia arena, playing the album in its entirety. Going back to the original masters was a surprising experience for Andrew Innes. “I hadn’t heard the tapes for 20 years,” he told me, “and the imagination that went into the record is what struck me. I was going, ‘God, listen to that sound, where the fuck did we get that from?’”

Hugo Nicolson meanwhile has his own theory as to why Screamadelica is now regarded as a classic album. “I think a lot of it is people remembering a time where it was ‘fuck this’ and ‘fuck that’, but with a very positive attitude, with ecstasy really helping a social attitude. It wasn’t like ‘fuck you and get the fuck out of here.’ It was like ‘fuck this and I love you so much!’ It had the punk ethos of, like, we can do this, no matter how limited our situations. But it didn’t have the aggression of punk. It had a love aspect.”

“That album,” reflected Bobby Gillespie, “was a result of being into acid house and mixing it with dub reggae, ’70s soul, the blues, the Stones and psychedelia. It felt like a really creative time. We were up for days and that record’s got that euphoria of the time.”