The Chic line-up around the time of the release of their second album C'est Chic. From left: Nile Rodgers, Luci Martin, Bernard Edwards, Alfa Andersen and Tony Thompson.Photo: Michael Ochs Archive / Redferns

The Chic line-up around the time of the release of their second album C'est Chic. From left: Nile Rodgers, Luci Martin, Bernard Edwards, Alfa Andersen and Tony Thompson.Photo: Michael Ochs Archive / Redferns

They might have been the greatest production team of the disco era, but even Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards could fall victim to the elitism of New York's club scene — and their response was the most memorable of all Chic's hits.

"We sort of knew we were a hit machine even before we got signed," says Nile Rodgers about himself and his late writing/production/ performing partner Bernard Edwards. "When you're in a groove and hit that stride, it's just amazing. It's like any great sports team or any person who has a string of superlative achievements — for a while you just can't be beat. It's what we used to call being in the zone. When you get in that zone, you can't do anything wrong. You're firing on all cylinders, all the dots are connecting and there's no self-doubt. Yet, inevitably, there comes the day when you wake up, you think you're doing the same thing, and it's not there. Even the greatest talents experience that, whereas when you're in the zone you feel like you can go on for ever."

Rodgers has spent more than his fair share of time in that hallowed zone. Not only did he write, produce and play on some of the most popular and influential songs of the disco era for Chic, Sister Sledge and Diana Ross alongside his fellow New Yorker, Bernard Edwards, but he has also created hit records for an eclectic array of artists, including Madonna, David Bowie, Deborah Harry, Duran Duran, Mick Jagger, Al Jarreau, Jeff Beck, INXS and the B-52s.

Born in 1952, Nile Rodgers was a guitarist in the Harlem Apollo's house band by the age of 19, playing with anyone from Aretha Franklin and Ben E King to Parliament Funkadelic and the Cadillacs. Still, what he really wanted was his own band, so after teaming up with bassist Bernard Edwards and playing in a number of different line-ups, the pair formed dance outfit Chic with drummer Tony Thompson, as well as singers Norma Jean Wright and Alfa Anderson. Signed to Atlantic Records, the act's eponymous 1977 debut album spawned the Top 10 singles 'Dance, Dance, Dance (Yowsah, Yowsah, Yowsah)' and 'Everybody Dance', while 1978's follow-up, C'est Chic, was a dance floor apotheosis courtesy of songs such as 'I Want Your Love' and that international chart-topper, 'Le Freak'.

Chic would still be at the top of their game with 1979's Risqué, featuring songs like 'Good Times', whose bass line was appropriated for both the Sugarhill Gang's 'Rapper's Delight' and Queen's 'Another One Bites The Dust'. Rodgers and Edwards would enjoy further smash-hit success with Sister Sledge's We Are Family album and Diana Ross's Diana, before disco took a dive and Rodgers began carving out his own production career in the early 1980s. He and Edwards would reform Chic during the early '90s, and it was a few hours after his participation in a tribute show to Nile Rodgers at Tokyo's Budokan on April 18, 1996, that Bernard Edwards tragically died of pneumonia. However, if one song should stand as a testament to their partnership, it is 'Le Freak', the groove to rival all grooves, featuring Rodgers' super-funky rhythm guitar, Edwards' pulsating bass line, and stripped-down production values that flew in the face of disco's traditional excesses.

Accordingly, it's interesting that, had the composers followed through on their original intent, the song would have conveyed a very different message...

Locked Out

"On New Year's Eve, 1977, we were invited to meet with Grace Jones at Studio 54," Rodgers recalls. "She wanted to interview us about recording her next album. At that time, our music was fairly popular — 'Dance, Dance, Dance' was a big hit and 'Everybody Dance', although more underground, was doing very well, too — but Grace Jones didn't leave our name at the door and the doorman wouldn't let us in. Studio 54 was that kind of place. Our music might be playing inside, but the place was packed for New Year's Eve and this was early in our career. Anyway, my apartment happened to be one block away, so Bernard and I went there to sort of quell our sorrows. We grabbed a couple of bottles of champagne from the corner liquor store and then went back to my place, plugged in our instruments and started jamming.

"You see, music was not only our livelihood, it was also our entertainment and recreation. And since we were feeling bad, we played music to make us feel good. We started jamming on the now-famous riff — Bernard and I were particularly good at making up riffs and jamming together. We were really into jamming and we'd often start writing songs that way, sometimes drawing on ideas that were floating around. In this case, however, the riff was super, super simple, so it didn't have to be pre-planned. It's not like I'd been saving it. It was just something that happened. I had always liked the [Cream] song 'Sunshine Of Your Love', and I wanted to do a sort of riff song for Chic, although not a complete linear riff — that wouldn't be like Chic — so I incorporated a little linear lick and we started singing, 'Fuck off!' [Repeats the lick.] 'Aaaaahh, fuck off!' Nile Rodgers today.

Nile Rodgers today.

"We were so pissed off at what had happened. I mean, it was Studio 54, it was New Year's Eve, it was Grace Jones, and we were wearing the most expensive outfits that we had — back then, in the late '70s, our suits must have cost us a couple of thousand bucks each, and our really fancy shoes had got soaked trudging through the snow. So 'Fuck Off' was a protest song, and we actually thought it was pretty good — 'Aaaaahh, fuck off!' It had a vibe. I was thinking 'This could be the anthem of everybody who gets cut off on the street by a cab driver or any kids who want to say this to their parents.' You know, 'Hey, I wasn't saying it, man! I was just playing the record.'

"We really had pretty big designs on completing the song as 'Fuck Off'. You've got to remember, we didn't think of that prior to sitting down and playing. Once we did sit down and play and started singing that hook, it sounded good; just as good as 'freak out'. In fact, had we not come up with 'fuck off' we would never have written 'Freak Out' and some other song would have been our big hit record. We were screaming it: 'Aaaaahh, fuck off!' Bernard and I usually wrote the hook of a song first, and then once we felt we had a chorus that would pay off, the rest of the song would follow. So, that night we actually converted 'fuck off' to 'freak out'. That was part of the process that first night. First, we changed it from 'fuck off' to 'freak off', and that was pretty hideous. We were singing it and just stumbling over 'freak off', because it was so lame by comparison. Then, all of a sudden it just hit me. For one second the light bulb went on and I sang 'Aaaaahh, freak out!'"

Building The Brand

"I'm going to tell you a secret that not many people know," says Nile Rodgers. "Every single Chic record is exactly the same, so to speak. The concept of a Chic album is that we're the opening act for a really big star, and we're unknown. No one has ever heard of us, we're brand new, and we're a live band coming out on stage to tell everybody who we are. So, there's always a song on the album that announces we're Chic — on the first album it's 'Strike Up the Band', on the second it's 'Chic Cheer', and so on. The concept is that we're an R&B band playing live for an old-time R&B audience. People came to those old-time shows to be blown away. They came to see the star, but the opening act was important too, so the opening act had to put on a really good show.

"That's been the formula for each of Chic's albums: we come out on stage, tell you who we are and what we're all about, and then we have to do some dance songs, instrumentals, slow songs and some hits. We've never strayed from that. After all, that's what R&B bands did in the old days — if you went to see Parliament Funkadelic, they could be an opening act and you'd never heard of them, but after that night you'd know who they were. Same thing with the Ohio Players, same thing with the Commodores. All R&B bands had the same concept. And if you see a Chic show live now, that's what we do — you know, before we walk onstage, the announcer says 'The man who brought you hits like "Everybody Dance"! "Le Freak"! "Good Times"...' It's really old-school.

"If you look at the Chic formula, if there was a formula, the longest song on each record was usually the single, and it was written that way. That was also the case with 'We Are Family'. As much as we loved Sister Sledge's album [of the same name], and as good as 'Lost In Music' was, it would have been the equivalent to 'Everybody Dance'; that real super club record, not as mainstream, even though it was a better song. 'Lost In Music' was a better song than 'We Are Family' or 'He's The Greatest Dancer', but because it was a better song it was not as commercial. In fact, 'Everybody Dance' was one of the best songs we ever wrote, but it was not nearly as commercial as 'Le Freak' or 'Dance, Dance, Dance' or 'I Want Your Love'."

Still, that didn't mean that the co-writers/producers ever gave away what they considered to be sub-standard material or kept the best songs for themselves. "We didn't have to, we didn't think like that," Rodgers asserts. "We considered ourselves an inexhaustible hit machine, so every time we got an assignment we thought we'd write the best stuff that we could ever write. And it really was that way for a while. To me, on some level, the songs kept getting better. By the time we got to work with Diana Ross, when people thought we'd already lost it because it was after the whole 'disco sucks' thing, we were writing some pretty interesting songs that we could have never written for Chic. We would have neve been able to write 'I'm Coming Out' or 'Upside Down' for Chic or Sister Sledge."

Dancing Days

All in a night's work. Inspired by their catchy hook, Rodgers and Edwards quickly realised it would fit perfectly with a twist-style dance record. You know the type of thing: come on everybody, put your right hand here, put your left hand there, wiggle your backbone and kick your feet in the air... the only thing was, the song's composers didn't have any dance steps to explain because they didn't have a clue as to what that dance should be. So much for their offer to 'show you the way' in the last line of the first verse — these guys were musicians, not choreographers.

"Normally, whenever we wrote a song about dancing, this was a euphemism for something else," Rodgers explains. "It could be about making love, life, whatever. We never specifically wrote about dancing, except maybe on our first record, 'Dance, Dance, Dance'. Therefore, in this case, even though we were saying something along the lines of 'Come on, baby, let's do the twist,' you'll notice that the lyrics aren't like those of a classic dance song, telling people what to do. There's no mention of how to do the dance, and that's because it was really about being pissed off and it was about Studio 54. We simply talked about what we believed was going on inside, since we didn't get in and didn't know! 'Have you heard about the new dance craze? Listen to us, I'm sure you'll be amazed. Big fun to be had by everyone. It's up to you, it surely can be done.' We didn't know how the dance went!"

What a way to start a new craze. It was fortuitous that 'freak' rhymed with 'Chic'. At this stage in their career, Rodgers and Edwards pretty much shared the writing and production chores, and in both regards they ensured that Chic was all about the rhythm section, about the guitar and bass. They didn't have a set formula.

"We were guessing at everything," says Nile Rodgers. "We would go out and do research, hanging out in clubs. It was a really exciting time. Before we became Chic we were a jazz fusion band, yet we gravitated towards pop R&B and we did it so well. We were able to be true to it, and we did that by internalising it and making it our life. Because a lot of times, when you hear jazz musicians play pop, it's not very pop. It may be pop to them. So, the fact that, at 25 years old, we intrinsically understood what the market wanted and also understood what older people liked meant that we embellished some very simple songs with interesting chord changes that nobody else can play. And it's still like that today. I play Chic songs with some of the greatest musicians in the world, and they find them difficult even though they sound simple. Bernard and I had a unique style and a lot of technical virtuosity went into our playing. Our right hands never stopped moving."

By the end of the aforementioned New Year's Eve, Rodgers and Edwards had solidified the hook and groove, and they also knew that the break would follow the second chorus. Grace Jones and Studio 54 could take a hike — having downed a couple of bottles of champagne, these guys were having a blast because they knew they had a smash hit on their hands.

"It was so clear to us, we decided to give our single to Sister Sledge," Rodgers states. "You see, before we wrote 'Le Freak', the first single off Chic's second album was going to be 'He's The Greatest Dancer'. We didn't write that for Sister Sledge. I mean, listen to the lyrics: 'One night in a disco, on the outskirts of Frisco, I was cruisin' with my favourite gang...' That was our single, but 'Le Freak' was so good that we changed our minds. And you know that it had to be really good for us to give away a song like 'He's The Greatest Dancer'. That was a smash for Sister Sledge, and we followed it with 'We Are Family'."

Chic Family

During the late '70s, Rodgers and Edwards had the Power Station's Studio B block-booked, and they also worked alongside a young engineer by the name of Bob Clearmountain. "He was with us from the beginning, recording 'Dance, Dance, Dance', and he taught me everything," says Rodgers. "It's incredible to work with somebody who's so professional and so seasoned and so together, and he's also a really good bass player himself. Bob was very aware of what we were doing, while also schooled in the tradition of [Power Station founder/engineer/ producer] Tony Bongiovi and the whole R&B sound, and that was great because it meant we could just go in and create while our engineer got the sound together."

The late Bernard Edwards, "the greatest partner in the world", at the Power Station.Photo: Ebet Roberts/Redferns

The late Bernard Edwards, "the greatest partner in the world", at the Power Station.Photo: Ebet Roberts/Redferns

The equipment that Clearmountain utilised for the sound while Rodgers and Edwards created 'Le Freak' was a 24-channel Neve 8078 console and 3M tape machine. "Every record was 24-track, and it took me a real long time before I switched to 48-track," says Rodgers. "Probably the first time I ever used 48-track was when I was doing Duran Duran's Notorious album [in 1986]. Madonna's 'Like A Virgin' was recorded on just 18 tracks; no background vocals, nothing. The only vocal I doubled was Madonna singing the chorus. It was just a simple, simple, simple recording. I told her that her first album was brilliant, but it was so electronic and technical that the subliminal artistry of Madonna didn't come through. I thought that if she made a more organic record, even though it was a dance/pop record, people would relate to her artistry in a way that would be astonishing. And she trusted me and went for that, and she's never made a bigger record. I don't think she's ever even come close, and nor have I. It was that magical thing at the right time." Engineer Bob Clearmountain also made his name through his work with Chic.

Engineer Bob Clearmountain also made his name through his work with Chic.

That January of 1978, Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards worked on the C'est Chic and We Are Family albums at the same time and in the same place, recording the basics in the Power Station's Studio B followed by string overdubs in the much larger Studio A. This amounted to bouncing from one session to the next and an around-the-clock work schedule for Messrs. R and E, as well as the musicians who played on both records.

"We had our crew, which was sort of our extended Chic family," Rodgers explains. "Everybody from [vocalist] Luther Vandross and [concert master] Gene Orloff to [percussionist] Sammy Figueroa and [keyboard player] Raymond Jones; all the best singers in New York and what I considered to be the best musicians in New York. And the best engineer. And the best recording studio."

Everybody Gains

Throughout Chic's career, Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards were very conscious of the need to keep their public profile high, and were also aware of the boost that the association could give musicians who worked with them. "We were pretty clear about what we were doing on each record. Right from the word go, when we had our first hit, the person who really made us super-confident — and I've never said thank you to this guy the way I should have — was Jerry Greenberg, the President of Atlantic Records. He said 'You guys can do so great for yourselves. Can you do it for other people, too?' We didn't know we could. We just said we could. We said 'Well, absolutely!' and that's when he offered us the whole roster, from Bette Midler to the Stones, take your pick. We chose Sister Sledge. You see, we kept thinking that if we worked with a big star and we got a hit, we'd be obscured by the big star and nobody would know what we did. But if we took somebody who was unknown and put them on the map, then everybody would say 'Wow, these guys are star makers and hit makers!'

"If you look at Chic album credits, we never specify what song anyone plays on, and that is because Bernard and I wanted everybody to go out and be successful. We used to say to them 'Look, if no one knows what you did, but they know that you're on it in some way, I don't care if you lie and tell people "Oh yeah, I did that song."' We used to tell them to do that all the time, and they did. Like with David Bowie's Let's Dance, no one knows what songs Tony Thompson played on because I never put that in the credits. They say 'Drums: Omar Hakim and Tony Thompson.' So, when you see the video and you think 'Oh, that's Tony playing on "Modern Love",' I go 'No, that's Omar Hakim playing on "Modern Love". Tony Thompson is playing in the video because he was on tour with Bowie.' So, we did that purposely and I still do that to this day. I just want it to be a sort of communal effort. And I admit that I love looking at credits and saying 'Oh shit, that's who played bass on that song,' but with Chic it's more about the collective organisation, it's not about who played what on what."

Freak Crew

The line-up Nile Rodgers recalls playing on 'Le Freak' was himself on guitar, Bernard Edwards on bass, Tony Thompson on drums, Rob Sabino on acoustic piano and either Raymond Jones or Andy Schwartz on Fender Rhodes, together with the Chic Strings comprising violinists Karen Milne, Cheryl Hong and Marianne Carroll, and singers Alfa Anderson and Diva Gray.

"Alfa's voice is instantly recognisable to me by the way she sings 'I'm sure you'll be amazed'," Rodgers says. "The word 'amazed' is kinda flat and very Alfa Anderson; a cool thing that we used to love. Still, 'Le Freak' is mainly about the music. There's probably more playing than singing. The bridge, for instance, is a couple of minutes long, but amid all the playing it only has a few words: 'Now freak! I said freak! Now freak!' The music is driving the whole thing along. In fact, the vocals were recorded after the backing track. With Chic we never did guide vocals, and no vocalists ever heard the song before they recorded any of our records, even if they were stars — Sister Sledge never heard 'We Are Family' until they got to the studio, and Diana Ross never heard 'I'm Coming Out' until she got there. Hearing these records for the first time, the artists were excited by them and wanted to prove they could do a good job. That made them concentrate and give a fresh, exciting performance. At the same time, the way Bernard and I worked with vocalists, we'd really coach and push them: 'Come on, you can do this!' We had a very definite idea as to what kind of vocal we needed.

"The rhythm track was always played completely live, without a click track, and we'd select one particular take. No song that we ever, ever, ever recorded was compiled from different takes. We knew which take was it because that's the one we kept, and then we'd overdub onto that. There are no alternative takes on anything. If we weren't satisfied with a take, it didn't live. We'd make up our minds right on the spot — we'd play it, listen to it and go 'Uh, that was good. Let's try another one.' And then if we tried another one and it was better, that's the one we would keep and we'd erase the other one. So, there is only one 'Le Freak'.

"I almost wish the world was like that now, because I'm working on a new Chic record and I must have 50 albums' worth of music here. I'll probably have a hundred albums' worth of music to complete the one album, whereas when we did Chic and Sister Sledge at the same time, however many songs were on each album, that's how many takes we did! That was how the world was then. Also, we were young and we believed in our ideas. We didn't need two [takes]. One was enough."

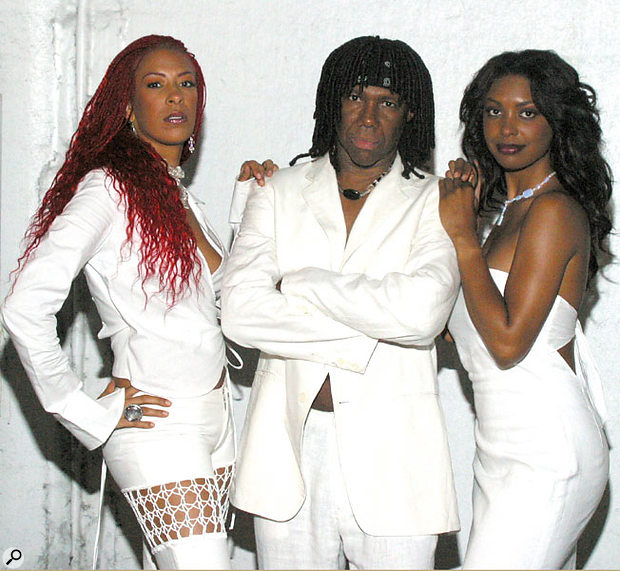

The current line-up of Chic, with Nile and singers Sylver Logan Sharp (left) and Jessica Wagner.

The current line-up of Chic, with Nile and singers Sylver Logan Sharp (left) and Jessica Wagner.

Time Is Money

According to Nile Rodgers, recording the rhythm track for 'Le Freak' was a breeze — he wrote out the charts for everybody and they performed the desired take within a matter of hours. Indeed, their parts for both the C'est Chic and We Are Family albums were completed within a couple of weeks, Rodgers playing his DI'd 'Hitmaker', a 1959 maple-neck Strat that he still uses to this day, and Edwards playing his DI'd Music Man bass. Once the rhythm section had done its job on 'Le Freak', all of the sweetening took place — including the horns and those good old disco strings — before the vocals were recorded at the tail end of the whole process.

"We were professional musicians, so everything was organised like a business, so to speak," Rodgers explains. "We did everything in the most economic way possible, and that meant we did all the strings at one time, all the horns at one time, and then all the singing. Because, growing up in the studio, we knew it was about saving money. As Madonna always used to say 'Time is money, and that money is mine.' So, we'd set up string dates for the whole record and do those in two or three days, we'd do the horns in two or three days, and then the vocals in two or three days, and the record was done. It was all very, very methodical. It was like building a house; the same every time. And all the while the songs were growing up and becoming better. We'd write the song and there would usually be some kind of outline, but then the lyrics would change and everything would change in the studio. It didn't matter what it was. You know, when we did the Diana Ross record, we had the whole New York Philharmonic in the room and we were changing charts right there on the spot. Even when I did films with big orchestral scores, like Coming To America, I was changing stuff right there.

"The cool thing about our records is that we played them long, so the arrangement was pretty much what it is. We came from that R&B school of arranging, where a song's creation was an odyssey, if you will. And people were listeners in those days. They wanted to listen and they wanted to dance and they wanted to experience stuff. They wanted to be entertained. They wanted to be taught. They didn't just want to be. I gotta tell you, I miss those days. I miss being that artistic. We presupposed a certain amount of effort on the part of the listeners; that they'd want to come and hear something different. Now, when you go to a show, no one wants to hear anything new. They want to go and hear what they like, as well as everything that they know. You play something new, that's when people go to the bathroom."

Chic Tricks

The number of effects available in the studio was on the rise during the late '70s, and although it didn't compare to what's on offer today, Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards were, according to Rodgers' own description, "the commercial kings. We used every trick in the book." If equipment was available, they'd use it, and it was also their policy to actually buy a new piece of gear for every new record project.

"We were a very gimmick-oriented band," Rodgers comments with regard to Chic. "The first trick we used, taught to us by Bob Clearmountain, was what sounded like a megaphone on "Dance, Dance, Dance (Yowsah, Yowsah, Yowsah)". This was a filter rolling out the high- and low-end frequencies. Then there was the gimmick of my rhythm playing — which was pretty accurate, pulsing on the money — being used as a trigger for other instruments that weren't playing nearly as funky. On the very first record that we recorded, 'Everybody Dance', we did it with one of my jazz-musician friends playing Clavinet, and he was not funky at all. So, when you hear that really cool solo that he plays on the song, it's actually him just playing whole notes while the rhythm is keyed by my guitar. That was our very first recording, and Bob Clearmountain taught us how to do that. He said 'Oh man, the keyboard player sucks! Why don't you play the rhythm, Nile, and just let this guy play whole notes.' I said 'You can do that?' and he said 'Yeah, he'll play and you'll make the rhythm for him.' I said 'Ah man, is that cool!'

"We'd use that trick quite successfully later on, the most successful being on the Diana Ross song 'Upside Down', where I keyed the funky rhythm of the strings. They played it straight; there was no way they could play like that. I'll never forget when we turned that record over to Motown — they took it and remixed it — and we asked 'What happened to those funky strings? I can't believe you guys erased those funky strings!' I can still hear myself: 'What kind of engineers have you got? They couldn't figure that out?'"

Nevertheless, while effects were the order of the day, 'Le Freak' was less of a standout in this regard. "That didn't use too many gimmicks, because the song in and of itself was a gimmick," Rodgers explains. "The only major gimmick was the huge echo on the bass drum following 'Aaaaahh, freak out!' That was achieved by just overloading the live echo chamber, which was the bathroom at the Power Station."

Team Work

As co-producers, Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards both took care of all aspects of making a record. "It was a real collaboration," Rodgers confirms. "I did the bulk of the songwriting because my output was just greater, but there was nothing sacred about it. Bernard always put his two cents in. And he was the greatest partner in the world. His opinion was really highly valued. It was always spot-on. He was so great and so economical with his opinions. He'd say 'You think that should be happenin'?' I'd go 'Yeah, I think it's pretty happenin'!' He'd say 'All right. I just wanted to know before I go and figure out a part for that bullshit.' That's how he was. Sometimes he would say 'Well, I was just testing you to see if you really liked it. Because if you really like it, then I'm gonna really try to come up with something great.' We'd each veto things that the other liked, and that happened all the time. He'd say 'Hey, you played that on the last record.' I'd go 'Really? Where?' He'd say 'Like, you know, the third bar... ' 'Oh... Yeah.' We were always striving to be original."