Seven top 10 singles isn't bad going for a career, let alone one album, yet that's precisely what Bruce Springsteen achieved with his smash hit 1984 LP, Born In The USA. This is the story of how it was made...

Bruce Springsteen on stage with his trademark Fender Telecaster.Photo: Larry Busacca/Retna

Bruce Springsteen on stage with his trademark Fender Telecaster.Photo: Larry Busacca/Retna

The mid‑'80s were the apex of Bruce Springsteen's still‑flourishing career. Not only did Born In The USA become the most successful album he has ever released — selling more than 15 million copies in America and 30 million worldwide — but it spawned seven top 10 US singles, tying it for the record that is currently also held by Michael Jackson's Thriller and Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1814. To date, those songs — 'Dancing In The Dark', 'Cover Me', 'Born In The USA', 'I'm On Fire', 'Glory Days', "'I'm Goin' Down' and 'My Hometown' — still comprise more than half Springsteen's present tally of 12 top 10 hits, while the title track is a radio staple and a regular at Fourth of July celebrations.

Nevertheless, despite its anthemic chorus and the fact that President Ronald Reagan tried to utilise the song for his 1984 re‑election campaign, 'Born In The USA' is not the energetic paean to flag‑waving patriotism that many people initially thought — and some still think — it to be: "I got in a little hometown jam / And so they put a rifle in my hands / Sent me off to Vietnam / To go and kill the yellow man.”

Focusing on a small‑towner who, after trading jail time to serve his country, returns home an outcast and can't even find work at the local refinery, Springsteen's song, far from appealing to the jingoistic, actually flushes the American Dream straight down the toilet. And it does so with a intense passion that is stirring and infectious. That is, on the hit version, with its thunderous drums and then‑contemporary synth backing. Yet, as originally recorded by 'The Boss' and eventually issued on his 1998 Tracks four‑CD box set, the acoustic demo is, in line with its desolate message, both stark and funereal.

Meet The New Boss

The Power Station on West 53rd Street in Manhattan.

The Power Station on West 53rd Street in Manhattan.

It was in 1981 that writer‑director Paul Schrader asked Bruce Springsteen to write the title track for a movie about a blue‑collar bar band. This had the working title Born In The USA, and Springsteen came up with the song of the same name while working on a track called 'Vietnam'. Schrader would eventually rename his film Light Of Day after Springsteen, who turned down the lead role that subsequently went to Michael J Fox, provided him with a replacement song in the form of '(Just Around The Corner To The) Light Of Day', recorded by Joan Jett.

"'Born In The USA' didn't sound like the Bruce Springsteen that I had mixed on his previous two records,” says Toby Scott. "I didn't know what Bruce wanted the track to sound like, but what the producers and I definitely knew was that it sounded sensational.”

In addition to serving as an engineer on 18 Springsteen albums and numerous live performances, Scott has also recorded artists ranging from Bob Dylan, Natalie Merchant and Steve Perry to Manhattan Transfer and Little Steven & The Disciples Of Soul. Musically inspired by the Ed Sullivan Show TV appearances of both Elvis Presley in 1956 and the Beatles in 1964, Scott taught himself to play guitar as a high‑school student in Santa Barbara, California, during the mid‑'60s. Then, after playing bass in some local garage bands, managing a couple of them, studying music theory and orchestration in college, and working for concert lighting and production companies in conjunction with acts such as Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin and Blind Faith, he began engineering, recording his own songs with a TEAC 3340S simul‑sync four‑track tape recorder and six‑channel Sony mixer.

In 1975, two six‑week engineering courses led to Scott securing a job at LA's Clover Studios, owned by A&R/producer Chuck Plotkin. There, in the course of assisting on an album by Robert Palmer and recording others by Booker T & The MGs and Harry Chapin, he honed his craft by learning from the likes of Steve Cropper, producers Tom Dowd and Steve Smith, and engineers Phill Brown and Richard Digby‑Smith. It was quite an education, yet Scott still had plenty to learn about Bruce Frederick Joseph Springsteen when, in the spring of 1978, he first encountered the man with whom he would forge his most prized professional relationship.

"I had heard of Bruce some time earlier as being 'the next Bob Dylan', but that was about it,” Scott now recalls. "Then, when Chuck Plotkin came in with this kid, I quickly realised he was about the same age as I was, about the same size, about the same everything — we were like two peas in a pod. We both weighed about 130lbs; I'm 5'11”, Bruce is 5'10”, and he was very down‑to‑earth. Chuck needed to mix one of the songs for the Darkness [On The Edge Of Town] record, and after we spent one or two days on it we sequenced the record and mastered it.”

Working The Room

The layout for 'Born In The USA' in the Power Station's (now Avatar Studios) Studio A.

The layout for 'Born In The USA' in the Power Station's (now Avatar Studios) Studio A.

Following this assignment, Toby Scott became Clover's manager and chief engineer, and just over a year later he began combining these roles with independent work at other studios. In 1980, he assisted Chuck Plotkin on the mix of Bruce Springsteen's album The River. This was after Neil Dorfsman and Bob Clearmountain had already tried their hand at it.

"I went into Clover on a Monday and put up a mix,” Scott recalls, "and Bruce, who would always stay in the upstairs lounge, came down to listen and said, 'It sounds pretty good, but it sounds funny. It doesn't sound right.' I said, 'Well, what's wrong?' and he walked behind the console and said, 'The drums. Didn't we use some room mics?' I said, 'Yeah, they're on these two faders.' I had them all the way down, about an inch from the bottom, and Bruce took them and jammed them all the way up to the top. Immediately, the sound was all room, and so I said, 'Oh, OK... Well, now that I've got the concept of what you're looking for, let me just rebalance stuff.'

"I can't remember which song it was, but clearly he wanted the room in there, and that was fine — I roll with the punches. So, I rebalanced it for the room, readjusting stuff to account for the drums sounding like they were coming from the other end of a basketball court, and when Bruce came back down and listened he went, 'That's it! Great! Good deal!' The next day, we did another song. At that point, Neil [Dorfsman] was coming in, looking over my shoulder for the first 10 or 15 minutes and going, 'Now, this is the saxophone that we use, and then you use the guitar on this track for the first part of the solo and the guitar on that track for the second part of the solo...' This was how we worked on the Monday and Tuesday, and then on the Wednesday, after a couple of hours working on another song, I took a break, saw [Springsteen's manager/producer] Jon Landau out in the hallway, and when I asked him where Neil was he told me Neil was in New York. 'You're doing fine,' he said. 'Don't change anything, just do what you do.' Whatever the differences were in our mixing, they apparently liked my style.”

A Focused Mix Point

The track sheet from a safety copy of 'Born In The USA'.

The track sheet from a safety copy of 'Born In The USA'.

A couple of months later, Toby Scott found himself using the Record Plant's remote truck to record some Bruce Springsteen concerts. Then, after mixing Gary 'US' Bonds' On The Line album in March 1982 — for which Springsteen wrote seven of the songs, co‑producing them with Steven Van Zandt — Scott was asked to fly to New York to not only mix Van Zandt's own Men Without Women, but also to record Springsteen's Born In The USA at the Power Station.

"From noon until six, I was working at the Hit Factory, mixing Steve Van Zandt, and then from seven until one in the morning I was with Bruce at the Power Station, recording basic tracks,” Scott explains. "Eventually, Steve was so excited by the mixes and the perspective, he wrote four more songs that I recorded and mixed, and in all I ended up spending about four months in New York.

"Bruce had recorded The River at the Power Station, which he liked because of the ambience of the main room, but I had never worked in a control room like that. Most all of the control rooms in Los Angeles were of the dead variety, or acoustically treated so that anything by the speakers was live while the back of the room was dead [or, later, the other way around]. It was therefore strange being in the Power Station environment where everything was very live.

"The floor in the control room was wood, all of the walls were wood, the ceiling was wood, and the ceiling was not sloped whatsoever, whereas Los Angeles studios in the '70s and early '80s had gotten into this design that had a focused mix point. The Altec 604E monitors would be up on the wall above the control-room glass, pointed at an angle down towards a focused mix point. From there, the ceiling would be sloped down to about six or seven feet above the head of the focused mix point, and it was like sitting at the cone of a big speaker. The Power Station was just a rectangular room, with the speakers actually hanging from cables or track on the ceiling, and it was fabulous. To this day, I will declare the best rooms I have ever worked in are those that are either designed or run by active engineers: not people who used to do it, not people who think about doing it, but people who are doing it.

"Tony Bongiovi designed the Power Station, having worked at Media Sound for a long time with Bob Clearmountain as one of the assistants, and the whole place was set up for an engineer, or, more likely, an engineer/producer. It was ergonomically very functional and Tony had gone to extremes to get the main Studio A [live] room right, building multiple sides of unequal lengths that went into a pyramid shape and, after being dissatisfied with the initial sound, adjusting the distances between the vertical panelling boards of the walls. By the time I got in there, it was just a great‑sounding room — provided you used a little bit of sense, the drums sounded incredible.”

Troubleshooting

On the first day of Born In The USA sessions all was far from well, as Scott explains: "nothing came together... the sound was just a mish-mash.” Determined that this experience would not be repeated on day two, he therefore re‑analysed the main studio area for musician/instrument placement, including that of E Street Band drummer Max Weinberg. Utilising the drum‑miking setup that Scott had perfected with Jeff Porcaro, Weinberg enjoyed a bigger sound courtesy of Neumann U87 room mics that were on huge boom stands at the far end of the room, pointing up towards the ceiling.

"Neil [Dorfsman]'s recording of the room mics had been one of my problems when I mixed The River,” Scott explains. "There was so much cymbal in those room mics, I had to recreate the room by using the Clover studio and piping some of the drums back out over speakers into the studio to have them reverberate around, while also using reverb units. On the other hand, for Born In The USA I was somehow able to find a spot where the cymbals were at an even volume with the tom‑toms and things like that, so you merely got the effect of a room.”

While bassist Garry Tallent was in the main room with Max Weinberg and recorded with a DI and an amp miked with an Electro‑Voice RE20, saxophonist/percussionist Clarence Clemons was in the lounge, looking through the porthole of the studio loading door so that he could see Tallent and Weinberg, as well as Bruce Springsteen who sang and played his guitars in an iso booth to the right of the control room, adjacent to the mic closet. Steve Van Zandt was in his own booth to the right of the control room, and both his and Springsteen's guitar amps were in another booth across from the control room on the right‑hand side. Keyboardist Danny Federici, meanwhile, played his Hammond B3 through a Leslie. This was miked with a Neumann U87 on the top speaker and an RE20 on the bottom in a booth directly across from the control room on the left‑hand side, separated by a divider from yet another booth which housed Roy Bittan, who played the grand piano as well as a Yamaha CS80.

The Words Are The Song

"The entire E Street Band played live,” says Toby Scott. "Bruce sang into a U87, and while he may have redone his vocal, as a general rule he has always been very confident. He just sings his part and that's it, and usually the only reason we will do a second take is if he wants to impart a different inflection, sing with a fuller voice, whisper something a little bit more or change the words. After I'd started out recording him with a U87, he used a U67 for a little while because it was fuller and smoother. However, it was not quite as clear, and so I then miked him with a dual‑capsule Sanken CU41.

"As far as I'm concerned, the words are the song, so I want to hear them. Bruce is the most eloquent guy that I know, but his enunciation isn't always the greatest, so I try to do everything I can to make it really easy to hear his words clearly. The CU41 was really clear, and he used that up until about four years ago when he spotted a Telefunken [ELAM] 251 next to his mic in the studio. I go back and forth, recording both Bruce and his wife [singer‑songwriter Patti Scialfa], and back in the late '90s, after we'd experimented with several microphones, she decided that the 251 was the one that she loved. So, I found one and bought it for her, and I used to have both that and the CU41 sitting side-by-side in the little vocal area of their home studio setup. Well, one day Bruce asked what the mic was, and when I told him it was Patti's he asked, 'Why don't you use it on me?' I said, 'Because the one I'm using on you sounds fine.' He said, 'Can we try it?' I said, 'Sure,' and he said, 'OK, just open a track and I'll experiment.'

"You have to understand, Bruce and I hardly ever experiment. I pick the microphone that, in my estimation, is the one that will work, and I also have a philosophy that I don't want to waste an artist's time while I figure out how to do my job. However, in this case Bruce sang into the CU41 and into the Telefunken, and in the end he pointed to the 251 and said, 'Gee, I kind of like it. Can I use this one?' I said, 'Sure,' he said, 'OK,' and that certainly simplified my life. I now use the same microphone and the same chain for him and his wife. Since I'm not a close‑miking person, I usually start Bruce off at least six inches from the mic, with a windscreen about an inch or two in front of it. Then, for his acoustic guitar, I use an AKG 460, whereas back in 1982 I would have used a 451.”

Broken Reverb

"The tape machine in the Power Station's Studio A was a Studer A80, the console was a 44‑input Neve 8048, and that facility must have had around 10 reverbs. One of them was a five‑storey stairway that had been blocked off, where you could move the microphones and speakers up and down. Then there was the Ladies' Room, formerly the ladies' bathroom, which was an all‑tiled room that they used for very good drum reverb. Additionally, they had about five EMT 140 stereo plates, along with a Scandinavian knock‑off of the 140.

"The assistant there told me, 'We have this other plate, but it's broken.' I said, 'What's wrong with it?' and he said, 'The motor on the decay adjust is shot.' I said, 'Let's hear it,' and so he plugged it in, I ran a drum into it, and the decay boomed and rattled and kept on going for about three or four seconds. When I was told it was broken and nobody wanted to use it, I said, 'Perfect, I'll take it! Put my name on it for the duration of this project!' I wanted stuff that nobody else was going to screw with.

"You know, if you've got an EMT plate it's real critical, especially in a mix, and I would just dump every instrument on a tape full‑on into the reverb unit, into an EMT plate, so it was reverberating like mad. Then I would adjust the decay time on the plate, and I'd stop every so often to hear how stuff sounded, tuning it so that the decay time and the tempo of the song sort of correlated. After a few minutes you could actually listen to it and go, 'Well, jeez, it doesn't sound that bad,' even though all of the echo knobs were fully turned up on everything. If you get it to the point where a ton of echo is almost believable, you can then pare it down to a normal level and it'll just blend in so that you won't even realise there is echo on anything. However, that takes time and I didn't want to do that every night. So, when I tried the knock‑off plate I said, 'I'll use that. Just patch it in and don't even fix it.'

"I took the output of that plate and ran it through what at that time was the only gate, a Kepex. I set the Kepex for an external input of the bottom snare mic and I set it to close in about a second. Then, I fed the top snare drum mic into that reverb unit — it was the only thing that went in there — and that created the explosive snare drum sound that you hear on the album. A combination of Max hitting the snare, the physical sound of the drum, the room mics from the Power Station and then this four‑second plate reverb created this really tremendous drum sound, and the first song we recorded with that was 'Born In The USA'.”

Out Of Order

"In those days, Bruce had a particular way of teaching the band a new song. He wouldn't play it for them from the beginning to the end; he would teach them the different parts of the song, and not necessarily in the order that they appeared. So, he might start off by saying, 'Well, there's this part,' and play them a little bit of the chorus, showing them the chord changes. After that, he might say, 'Then there's this part,' and play them the bridge, and follow this with 'And then there's this part,' and play them a verse. While the guys would be making notes, he might say, 'Then there's this part, which is like an intro‑instrumental thing,' and if there was any other part, such as a solo, he'd teach them that, too. Then he'd ask, 'Everybody got that?' and if they did, he'd say, 'OK, we're going to start with the second part I showed you and then go to part number four. We'll play that twice, and then we'll go to part number one before going back to part number four, then on to part number three, back to part number four, back to part number one, then part number three again, then part number four, and then number one, number one and we'll ride out on one...' They'd be like, 'Huh?' and he'd go, 'All right, you want to run through it?' while the guys were scrambling to understand exactly how the song should be laid out.”

For his part, Toby Scott was able to understand Springsteen's modus operandi when the latter explained that, were he to teach the musicians a song from beginning to end, they'd immediately know all the chord changes as they transitioned from one section to another, probably resulting in contrived licks and less spontaneity. What he wanted to capture were those moments of inspiration that might emerge during the early takes, and such was the case with 'Born In The USA'. After explaining the structure, Springsteen went to his booth and set the tempo while his fellow musicians played through their parts. Then, once everybody was ready, Scott rolled tape and take one was recorded.

"I was in the control room, listening through my Yamaha NS10s at a reasonable volume, and then Chuck asked me to put it up through the big speakers,” Scott recalls. "So, that's what I did, and I remember listening to it and going, 'Wow!' Right from the start, the snare drum was exploding, and you have to remember this was 1982, when we were in the middle of disco‑land there in New York. There were no exploding snare drums in New York — there were no exploding snare drums anywhere — and then, what with Danny's synthesizer playing that grand intro, the song was just cracking away and I turned to Chuck Plotkin and Jon Landau and said, 'I don't know whether it's Bruce, but man, it sounds good to me!' They agreed.

"I'd gotten a good cue mix for everybody, so they all could hear it, and the takes were like 10 minutes long. On the final cut there's a rather long ride‑out, but it was even longer and we cut it down by three or four minutes. The band just kept playing. There were eight takes of the song, take six was the master — thanks to Max perfecting his bass-drum pattern — and when the band members came into the control room after the first couple of takes and heard the track, they too were going, 'My God, we've never heard anything like this before!' It was totally, revolutionarily different-sounding to anything else at that time.”

All Systems Go

Thereafter, with a sound perspective that Toby Scott could return to every night, the sessions proceeded quickly, with Springsteen delivering a steady stream of new songs, and in less than a month he and the band had recorded all of the material he felt he needed. About a week was then spent on overdubs before, in mid‑1982, Scott began mixing the album on an SSL console in the Power Station's Studio C.

"My perception was that the whole thing was moving a little too fast for Bruce,” Scott remarks. "All of a sudden, we were mixing a rock record that we had only started to work on a few weeks before. Normally, he'd spend several months on each record, and so in the middle of mixing he had us re‑enter Studio A to work on some other songs. He had demoed a few of these on a little TEAC four‑track back in January, and while some were for the band, others were more pared-down, maybe for him to play with just a couple of the guys, and one of those — not recorded on the TEAC — was 'I'm On Fire'.”

Recorded with Max Weinberg and Roy Bittan, this moodily atmospheric, synth‑based rockabilly track would be added to the album and released as its fourth single. However, many of the other songs that Springsteen had demoed on the TEAC were now given the full band treatment, before he quickly opted to go with the original four‑track cassette recordings and issue them on the Nebraska album. Released in September 1982, this had been completed a couple of months earlier while Born In The USA remained in limbo. It wasn't until February 1983 (by which time Toby Scott had quit Clover Studios to become a freelancer) that the sessions were revived for a week at New York's Hit Factory. They then resumed that May, when Springsteen cut 'My Hometown', and continued sporadically through the beginning of 1984, when 'No Surrender' and 'Bobby Jean' were both completed.

At this point, after Scott did some rough mixes at the Power Station, Bob Clearmountain was recruited to add his magic touch, and while Scott was retained as a consultant and sounding board, he considered his job largely done until, that May, Jon Landau persuaded Springsteen to compose an upbeat "here‑and‑now song” that could serve as the album's lead-off single. That song, written overnight and recorded the following day at the Hit Factory, was 'Dancing In The Dark'. To date, it is the most successful single of his career.

Born To Run & Run

Released on 4th June, 1984, Born In The USA was not only the best‑selling album of 1985 in the United States, but also the one to spend the most ever weeks — including its first 84 — on the Billboard top 10. In total, it was on the Billboard 200 for more than two and a half years, during which it shared another record — having topped the chart for four weeks from July 7th to August 4th, 1984, it actually spent 18 weeks at number two while Prince's Purple Rain resided at number one, marking the longest period with a fixed top two in the history of the Billboard 200. In January 1985, Born In The USA replaced Purple Rain atop the chart for another three weeks.

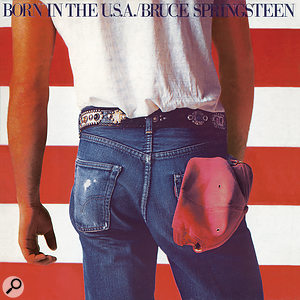

In the process, Bruce Springsteen elevated his status as the all‑American everyman, and while the title track may have misled those who paid no attention whatsoever to its lyrics, the iconic album cover that it inspired proved to be equally ambiguous. Shot by Annie Leibovitz, this depicted Springsteen from behind in a white muscle shirt and blue jeans, set against the backdrop of the US flag. This prompted some to assume that he was peeing on the Stars & Stripes, yet the man himself firmly denied this, explaining, "We took a lot of different types of pictures, and in the end, the picture of my ass looked better than the picture of my face... I didn't have any secret message.”

Artist: Bruce Springsteen

Track: 'Born In The USA'

Label: Columbia

Released: 1984

Producers: Jon Landau, Chuck Plotkin, Bruce Springsteen, Steve Van Zandt

Engineers: Toby Scott, Bob Clearmountain

Studio: The Power Station

Drum Miking: East Vs West

"Los Angeles was really into high fidelity and tube mics, and at Clover we had a very good and extensive selection of vintage mics from the '50s and '60s,” Scott explains. "However, when I first went to New York and suggested miking the drums with [AKG] 414s or [Neumann] U87s as overheads and a [Sony] C37 on the snare, it was totally out of the realm of what people used there. I mean, when people like Tom Dowd and Steve Cropper gave me advice, it was a case of 'Hey, that sounds good!' Thanks to them, I also used U67s on tom‑toms, but when I wanted to do this during my first gig at the Record Plant the reaction was 'Huh?'

"All they had were Shure SM57s, Sennheiser 421s and a few U87s. When I asked, 'Well, how do you record stuff?' I was told, 'We put those on everything.' I thought, 'Wow, I can't do that. I want some dynamics here.' I was always very much into the dynamics of the individual performers, yet dynamic microphones are not all that dynamic because there's an inherent compression that takes place due to the fact that you're moving the capsule around.”

Told that no studios in New York had U67s, Scott subsequently located some that he used, together with 421s, on the bass drum.

"Another part of my drum setup was to create a tunnel by using a second bass drum in front of the main bass drum,” he adds. "Since the second one had no head and was facing the main one, it didn't matter whether or not you had a head on the regular bass drum. I'd just put a microphone in the middle, pointing at the beater, and I got into this extensively with [session man] Jeff Porcaro, who was a drumming genius. He taught me that if the second bass drum was the same size as the main one and you tuned the head on that second one, you could then adjust the distance back and forth by a few inches so that it created this sort of compression chamber. The result was a great bass-drum sound, and by throwing a blanket over the secondary drum you wouldn't have a lot of bass drum leakage in the room mics while still getting a very large, open bass-drum sound.”

Miking Amplifiers

"At that time, if I recorded each of Bruce and Steve's electric guitars with two microphones, one of those mics would probably have been an SM57, positioned about two or three inches from the grille cloth. Generally, the actual sound of each amplifier would determine where I would point this microphone, not only in terms of angle but also position. One starting place is straight on, perpendicular to the grille cloth — you can start in the middle of the cone, you can move to halfway between the middle and the edge of the cone, or you can be all the way out at the edge. Then, the other option is to angle the microphone at maybe 30 degrees off perpendicular and move that across the axis so that it's looking straight down the side of the cone and pointing at the centre. These were all techniques that Porcaro had turned me onto when trying to get the drums to sound thinner or tubbier depending on where you pointed that mic along the head, from the centre to the rim.

"In addition to the SM57 about two or three inches from the grille cloth, often times I would also use a Neumann KM86 about three feet back, and both of these microphones would be recorded to one track since we were working 24‑track.”