Gerald Simpson playing live with 808 State’s Graham Massey at Manchester’s Victoria Baths, 1988.

Gerald Simpson playing live with 808 State’s Graham Massey at Manchester’s Victoria Baths, 1988.

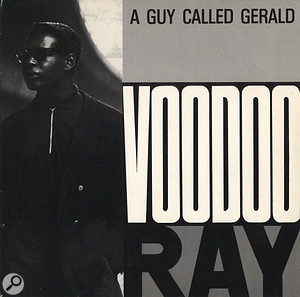

Hailed as the first British acid house single, A Guy Called Gerald’s sublime ‘Voodoo Ray’ has since become a classic in its own right.

The first acid house single produced in the UK, ‘Voodoo Ray’ by A Guy Called Gerald was an eerie and hypnotic dance record created in Manchester in 1988, at the height of what was known as the Second Summer of Love. Originally released that year on tiny Merseyside label Rham!, it sold out of its initial run of 500 12–inch singles within a day, requiring a very hasty repressing, before spending 18 weeks in the UK charts, peaking at number 12 in 1989.

Inspired by the house music sounds emanating at the time from Chicago and Detroit, ‘Voodoo Ray’ creator Gerald Simpson was a regular visitor to Manchester’s then acid house mecca, The Hacienda nightclub. “There was a lot of energy there,” he says today. “For me, it was a kind of ideas place. There was a melting pot of people, everyone from students to breakdancey–type people. I used to be amazed by the size of the place and what was going on in there, ‘cause I’d only been in these little clubs before. It just became a focal point of Manchester club life. I used to take advantage of going in there and then leaving from there and going to the studio.”

Roots

The story behind ‘Voodoo Ray’ is one of a synth and drum machine–obsessed individual who grew up in Manchester’s inner city area of Moss Side. Born of Jamaican parents, both Simpson’s father and mother had a notable effect on his early interest in music: the former through his collection of ska and bluebeat records, the latter due to her attendance of a local Pentecostal church where live music featured every Sunday. “They used to do a bit of talking about the Bible and then they would go into a jam,” Simpson remembers. “That was really great, really enjoyable when you’re a kid. ‘Cause it was loud [laughs]. Loud and with loads of energy.”

Louder still were the sound-system house parties that Simpson first experienced in Moss Side in the ’70s from around the age of 10. “I grew up in a really diverse place, but it was really safe,” he says. “It was in the middle of a ghetto, but you could leave your door open. Someone would be having a party and you’d be able to hear it and you’d go over. There’d be a sound system playing and you could just kind of hang out.

“The sound systems were pretty powerful and they were all homemade. People used to build their own amplifiers and speakers. It was interesting. I wanted to be a part of it.”

Simpson’s first real musical passion was for hip hop, beginning around 1982, when he was still at school. “There was a bloke who would come to school, he had a ghetto blaster and he would sell tapes,” he remembers. “Then, later on, he started an electro funk sound system. Anything electronic like that used to make my ears prick up, so I wanted to get one of these drum machines. Everyone was into getting the records and stuff. I was like, ‘Naw, I want that machine that makes them beats. I want to do it myself.’”

The first drum machine that he bought was the comparatively primitive Boss Dr Rhythm DR55, a step–time programming beatbox with only four sounds — bass drum, snare, rim and clap. “Tap tap, space, tap tap,” he laughs. “I started off with that, so I had this restriction. Then when you heard other stuff you’d be like, ‘Wow.’ You wanted to try and get to that stage.” It was 1986 when Simpson progressed to a Roland TR808, buying it second–hand for £150 from the A1 music shop in Manchester. “Going from the Dr Rhythm to an 808,” he says, “it was like, ‘Oh my God, I can do all this stuff.’”

At the same time, Simpson began to learn more about sound from listening to jazz fusion records on his cassette Walkman. “Mainly Weather Report, Chick Corea Return To Forever, and some of the experimental Miles Davis stuff like Bitches Brew,” he says. “I remember just recording stuff to listen to on the Walkman. I was amazed at the space. ‘Cause up until then I’d been hearing stereo, but I’d been hearing it through one broken speaker over there and another one over there. Getting a Walkman was just like, ‘Oh, I can hear everything how it was recorded. That’s amazing.’ I always used to try to get Japanese imports because they were digitally mastered.”

More than anything, Simpson says these albums taught him about sonic placement. “For me, a really important thing is imaging, just getting the stereo in the right place,” he stresses. “I see that as a painting. So you can either be a realist and go, ‘OK, well the bass drum should be here.’ Or you can go, ‘Let me be really weird with this, like I’m in a space capsule [laughs].’”

Another key part of Simpson’s musical development was the fact that as a teenager, he studied dance. “It was contemporary, jazz and classical,” he says. “It was really interesting for me because it made a connection between movement and sound. It made it easier for me, ‘cause I was trying to create stuff that’s gonna try and make people dance, y’know. It’s almost like synaesthesia where you see colours to music, you can see movement to a sound. I’m thinking of movements all the time.”

Judging by the copy of SOS in the foreground of this photo, we can assume it was taken in the summer of 1996. By this time A Guy Called Gerald was one of the pioneers of drum and bass and the Roland gear has largely been replaced by Akai equipment. Quickly, he found himself being drawn to breakdancing more than his more traditional dance studies and, learning the art of turntablism, began DJ’ing. “My style was more like performance DJ’ing,” he points out, “so it was cutting and scratching.” From here, Simpson formed a hip hop crew, the Scratch Beatmasters, along with Moss Side rapper MC Tunes. “We were really influenced by what was going on with the American music and some of the English stuff,” he says. “We were getting everything from everywhere, from New Order to hip hop and soaking it all in. But we didn’t have an outlet. And then when we found one, we just exploded. I wasn’t forcing myself to be creative. But it was just like, you can either sit on the high street with a can of Tennent’s or do something else.”

Judging by the copy of SOS in the foreground of this photo, we can assume it was taken in the summer of 1996. By this time A Guy Called Gerald was one of the pioneers of drum and bass and the Roland gear has largely been replaced by Akai equipment. Quickly, he found himself being drawn to breakdancing more than his more traditional dance studies and, learning the art of turntablism, began DJ’ing. “My style was more like performance DJ’ing,” he points out, “so it was cutting and scratching.” From here, Simpson formed a hip hop crew, the Scratch Beatmasters, along with Moss Side rapper MC Tunes. “We were really influenced by what was going on with the American music and some of the English stuff,” he says. “We were getting everything from everywhere, from New Order to hip hop and soaking it all in. But we didn’t have an outlet. And then when we found one, we just exploded. I wasn’t forcing myself to be creative. But it was just like, you can either sit on the high street with a can of Tennent’s or do something else.”

808 State

Along with his purchase of the Roland TR808, through working shifts at McDonalds, Simpson managed to get enough money together to buy a Tascam four–track and his first synth, the Roland SH101. From 1986 on, he became a regular of the Manchester shops which imported dance records from America, frequenting Spinning Records to buy electro funk 12–inches and Eastern Bloc Records to buy house. It was in the latter that he first encountered other key, kindred souls who were to prove crucial to his burgeoning music career. “I’d buy stuff from Eastern Bloc,” he recalls, “and I was saying to these guys, ‘I’ve got all these machines at home that make this music.’ And they were like, ‘Yeah, yeah.’ So I played them a tape and they were like, ‘What, you do this yourself? We’ve got this room downstairs in the basement you can use.’”

Simpson began working with Eastern Bloc owner Martin Price and a student sound engineer, Graham Massey, on dance tracks together at Spirit Studios in Manchester, originally as the Hit Squad, before they mutated into 808 State. Unusually for the times, where dance producers tended to work individually or in pairs, 808 State were a fully fledged band.

“Everything was really organic,” Simpson points out. “There were no turntables involved, there was no DJ’ing involved. It was all synthesis and drum machines and no loops. I’m not saying loops are a bad thing. But I think what’s kind of happened now is that people are forgetting the actual skills of synthesis and programming, by getting really lazy and just grabbing.”

Over an intensive weekend in early 1988, 808 State made their first album, Newbuild, which showcased a loose and playful home–grown British take on house music. At the same time, Simpson would take his machines back home to Moss Side to work on his own material, which he felt at the time was too dark and experimental to be presented to the other members of the band.

“At the time,” he says, “they were new to the whole thing with the synthesizers, so if I gave them the crazy shit that I was doing, they wouldn’t have bought it anyway. I thought it would’ve been a bit too weird for them because it didn’t sound like something from Chicago or Detroit. So I kept that stuff separate. And, yeah, it was a good thing [laughs].”

Timing Issues

‘Voodoo Ray’ began life as a home recording experiment for Gerald Simpson, when he was trying to multi–layer sounds on his Tascam four–track from the monophonic Roland SH101. “I mean, everything always starts off ‘cause you’re trying to do something else,” he reasons. “I was trying to mimic a polyphonic synthesizer using a monophonic synthesizer.”

In attempting to overlay a second synth part generated by the SH101’s internal sequencer, Simpson’s hit–and–miss method involved pressing play at the beginning of the recorded backing track and hoping the sequence would stay in sync. “I had an issue with timing,” he smiles. “To get the same sync, you had to really hit the thing on. It was really hard to do. But I managed to get this riff together.”

Over these two SH101 parts, Simpson added a sequence from the Roland TB303, the machine originally designed to be a bass line–playing partner to Roland’s TR606 Drumatix beatbox, but whose squelchy tones were co–opted by pioneering acid house producers. “I got the 303 to do a counter riff and I think it kind of covered up the timing,” he laughs.

To his growing collection of equipment, Simpson soon added a second SH101. “By then, I was hooked... I was a synth junkie,” he admits. “I didn’t realise it at the time, but it’s only later when I’ve seen friends go down the same path, I’m thinking, ‘Should I tell them they’re hooked?’ Nah, I’ll just leave them to it.”

Recently Gerald Simpson has rekindled his love affair with Roland X0X gear, as can be seen in this shot of his 2013 Rebuild collaboration with Graham Massey. Photo: Jan Cavens www.cavensjan.beWorking with this pre–MIDI setup, Simpson used two of the three trigger outputs from the 808 to link to the clock inputs of the SH101s, while the drum machine’s DIN sync out connected to the 303. Around the same time as figuring out how to link and synchronise these machines, Simpson bought an Akai S900 sampler, which offered just under 12 seconds of recording at its full sample rate. Being canny, the young producer found ways to work around this limitation.

Recently Gerald Simpson has rekindled his love affair with Roland X0X gear, as can be seen in this shot of his 2013 Rebuild collaboration with Graham Massey. Photo: Jan Cavens www.cavensjan.beWorking with this pre–MIDI setup, Simpson used two of the three trigger outputs from the 808 to link to the clock inputs of the SH101s, while the drum machine’s DIN sync out connected to the 303. Around the same time as figuring out how to link and synchronise these machines, Simpson bought an Akai S900 sampler, which offered just under 12 seconds of recording at its full sample rate. Being canny, the young producer found ways to work around this limitation.

“You could record something at a really high pitch and then play it down and you would have more time,” he says. “So I would record stuff and then I’d pitch it down and then I’d put it through an effect on the [Yamaha] SPX90 or something. So you’d pitch it down for more time, and then you’d pitch it up on the effect. Bit of a cheat, but needs must, to get things in.”

Running out of sample time on the S900 was to accidentally produce the title of ‘Voodoo Ray’. Lifting a spoken word sample from Peter Cook and Dudley Moore’s Bo Duddley sketch, from their 1976 comedy album Derek & Clive (Live), where Cook says “voodoo rage”, Simpson found that the sample had cut off, reducing it to what sounded like “voodoo ray”. Elsewhere in the track, the cry of “later!” comes from Moore.

“I used to collect spoken word records,” says Simpson. “‘Cause in my cutting and scratching days, they were kind of like gold dust. I used to try and do these megamix things where you’d cut in bits from obscure old movies and whatever. So if you could find movie soundtracks on vinyl, you’d be like, aw wow. So, yeah, he said ‘voodoo rage’ and I kind of chopped it.”

“The Sky Was The Limit”

In summer 1988, Simpson took the home–programmed parts for ‘Voodoo Ray’ into Moonraker Studios in Manchester. Using a SMPTE to DIN sync box to connect his 808–driven synth setup to the studio’s Fostex 16–track tape machine, he was able to layer sequences without timing issues. Suddenly, his sonic world opened up.

“By then, the sky was the limit,” he remembers. “It was just about that time when people started to discover Cubase. But I didn’t really want to go that way because it was really unstable at the time. I just wanted to create a tapestry on tape, because I’d started to do that with the Tascam four–track. I’d discovered how to record with the Tascam and find my own space for things. So I wanted to do that... I mean 16 tracks was almost too much. It was just crazy. All this space. So as well as being able to trick for time in the sampler, you’d be able to throw it onto tape and go back and still do things.” Given that the 808 offered the luxury of 11 separate outputs, Simpson began to experiment with treating the drum machine’s sounds with different effects. “The 808 was my main sequencer, but if you really wanted to, the drum could be the bass or it could just be a click in the background because you could have a cut-off. For EQ’ing, you could really get into it. With the snare, you could put more snap on it and get this biscuit-tin sound that I was really loving at the time, which worked really nicely with some Lexicon reverbs. You could create almost like this white noise from the reverb.

“You had one snare on the drum machine but you could make that snare sound like nearly anything you wanted. If I wanted a lower snare, I’d pitch the tape machine up a couple of ips and then when I’d put it back down to the normal speed it was like another snare. Then you’d put a reverb on it or something. So there were all these things that you could do. I used to love spending time treating every single instrument. At one point, I created a diagram of a perfect system, which was a grid-like snare, bass drum, hi–hat on one side and then on the other side I would have reverb, flange, delay, compression and then I would put one to the other.”

Elsewhere, Simpson experimented in ‘Voodoo Ray’ with mixing tones from his two SH101s. “I was trying to do something that someone told me later on is called heterodyning, where you use two tones to create an imaginary tone. The same sound but its two oscillations are creating a third oscillation. It’s like an audio illusion, with almost like a metallic sound coming from it in some places. It’s kind of going in and out of itself.”

The iconic female vocal sample on ‘Voodoo Ray’ was added when Simpson brought in session singer Nicola Collier, initially to work on other tracks. “We had a bit of time in the studio so we did four tracks on that day,” he recalls. “I remember we did this track called ‘Spend Some Time’, which was like a soul and funk track. I had the bass line already down for ‘Voodoo Ray’ and I can remember Lee [Monteverde, engineer] said, ‘Let’s just get Nicola to sing over the top.’ There was no words or anything so we just created a vibe and had her sing over the top of it. Then I just went in and grabbed a sample of what she was singing and reversed it and then played it backwards over what she was singing, which created this almost Asian–y sound. It was basically the sound reversed back on itself.”

When preparing ‘Voodoo Ray’ for mixing, Simpson and Lee Monteverde spent a lot of time cleaning up the sometimes unwelcome noise from some of the drum sounds. “He was really teaching me at the time how to get clarity in things,” Simpson says. “He was showing me how to properly record. We gated everything and compressed it. Basically we made sure that all the stuff that was on tape, it didn’t have any noise on it. Say there was a bit of hiss on the snare, that would’ve amplified when I started to put reverb on there. I wanted everything to be really clean, and the space around everything to be clean, so when it came to doing the stereo imaging, everything was clean and in its own space.

When preparing ‘Voodoo Ray’ for mixing, Simpson and Lee Monteverde spent a lot of time cleaning up the sometimes unwelcome noise from some of the drum sounds. “He was really teaching me at the time how to get clarity in things,” Simpson says. “He was showing me how to properly record. We gated everything and compressed it. Basically we made sure that all the stuff that was on tape, it didn’t have any noise on it. Say there was a bit of hiss on the snare, that would’ve amplified when I started to put reverb on there. I wanted everything to be really clean, and the space around everything to be clean, so when it came to doing the stereo imaging, everything was clean and in its own space.

“So the first thing was the cleaning, then it was the spacing and then we’d go into mixdown. It’s a process that I’ve stuck with over the years, even with software and stuff. I do a lot of cleaning and a lot of spacing. I love the way like these kids go, ‘Aw yeah I love this hiss, I want some tape echo with dirt.’ And I’m like, ‘Keep it’. ‘Cause I went through so much to get rid of all that [laughs].”

Test Pressing

Given that ‘Voodoo Ray’ was designed for the dancefloor, Simpson took the test pressing of the track first to Legends nightclub in Manchester and then The Hacienda to hear how it sounded on a club system. “The first time I heard it in The Hacienda, it really blew me away,” he says. “It was interesting. Compared to a lot of the stuff, the bass at the time was more protrusive.”

Due to its thumping bass and trancey groove, topped with its spooky vocal hook, ‘Voodoo Ray’ was an instant underground hit. “The label put it out, but in the style of someone who’s had stuff out already,” says Simpson. “They didn’t say, ‘This is the first track’, kind of thing. That was intentional apparently. They sold shedloads of them in a week. I mean, I wasn’t really concentrating on it, I was just getting on with stuff in the studio. Then I heard that it was in the charts.”

Off the back of the success of ‘Voodoo Ray’, Rham! Records asked Simpson to make the first A Guy Called Gerald album, Hot Lemonade, released in 1989. “It was like, ‘You need to do an album straight away,’” he remembers. “I mean, I had loads of material. I was just working on stuff constantly, so I just got back into the studio.”

At the same time, Simpson upgraded his home setup, incorporating a Soundtracs Quartz mixing desk. It was a development borne out of his realisation that, at the end of booked studio time, he didn’t ever want the session to end. “There were so many ideas and so many different ways I was learning about doing things,” he enthuses. “Doing all the creative stuff and then doing the more kind of technical stuff. I thought if you could have a balance of these things, basically it could be unlimited.”

Ooh Oo Hoo Ah Ha Yeah

Having launched his career with ‘Voodoo Ray’, Simpson has since produced 11 albums as A Guy Called Gerald. As a result, at the age of 48, he remains in constant demand, performing and DJ’ing all over the world. He stresses, however, that he is firmly against pre–produced DJ’ing. “You get people using Ableton Live with an entire mix already pre–done,” he says. “Then they’re standing there, pretending that the knobs on the mixer are too hot [laughs]. You kind of think, Is it all fake?

“That’s one of the reasons why I got back into using the Roland stuff, just trying to step out of only using the computers. I do use Reason to do live shows, but everything is serendipity and nothing is reproduced. It’s all stuff that I can do live. I wanted to try and do a gig where, instead of being on a podium like a DJ, I’m right in the middle of the dancefloor. So people can come up and actually see what I’m doing if they want. At the same time it gives me a chance to monitor exactly what’s going on on the dancefloor, so I’m working with them. I prefer to be on the dancefloor, having a bit of a dance with them and making the grooves at the same time.”

As far as ‘Voodoo Ray’ is concerned, Simpson doesn’t have a big theory as to why the track has remained such a dancefloor staple. “Yeah, I dunno,” he grins. “I’m totally confused. But it was part of an era that people still remember today. Probably one of the reasons is it was the first acid house tune from the UK. That might be the thing. If you go back to the start, you go back to there.”

Twenty seven years after its release, Simpson admits he is slightly sick of ‘Voodoo Ray’. “Kinda sick of it,” he laughs. “Twenty years ago I was sick of it. But it’s part of my history. I kind of always had a fear that it would get in the way to my progressing and doing other things. I mean, today I’ve got no worries with it. But at the time, as a young man, I was like, ‘Wow, if I put all my apples into this one thing, I’m never gonna move on, I’m not gonna be allowed to move on.’

“So I always wanted to move forward with what I was doing and try and get to another level. It’s nice to accept the compliments, but you’ve also got your own personal goals to achieve too. For me, it was trying to create a balance between the creativity and the technical side of things.”

When it comes to the latter, Simpson is very proud to now be an advisor for Roland, flying to Japan to check out prototype drum machines. For the once tech–obsessed teenager from Moss Side, this represents success far more than any record sales or big gigs ever could.

“Nowadays, going to Japan and talking to these people and going, ‘The drum machine’s really nice, but we could do this or we could do that,’ that to me is a pay–off,” he states. “Talking to someone at Roland about a drum machine, it’s like, wow. Some people have to have Grammys and gold records on the wall. With me, I’m happy and satisfied with that.”

Remixes

With his next A Guy Called Gerald album, Automanikk in 1990, Simpson secured a major deal with CBS. For a 12–inch included with its UK vinyl release, at the Roundhouse Studios in London, he reworked his most famous track as ‘Voodoo Ray Americas’. “It was basically just a lot of reprocessed stuff,” he explains. “I did that version because I was going on an American tour. By then I’d got an [Akai] ASQ10 [sequencer] and all the old-school stuff, I kind of decided I was gonna leave that at home and just sample everything. So I thought, on the album version, I’m gonna do a resampled version. There were a few things that were changed. There were some new instruments on it. But it’s just a bit cleaner in a way. It doesn’t sound so different.”

As a club classic, ‘Voodoo Ray’ has been remixed countless times down the years. Simpson says his favourite reworking of the track remains the one by Chicago house pioneer Frankie Knuckles, operating under the name Paradise Ballroom, who stretched the track out with bubbling percussion and piano breaks into over eight minutes. “He broke it down so he got this really nice flow,” Simpson says. “He just made it sound like more of a New York-style thing.”

These days, laughs the producer, new unofficial remixes of ‘Voodoo Ray’ are constantly being uploaded to SoundCloud and other sites. “There’s a few a week,” he says. “At first I was really angry about it. But I suppose it’s a way of people enjoying the tune.”