In 1956, Miles Davis was at Columbia Studios to record an album with the musicians who subsequently became known as his 'First Great Quintet'. Engineer Frank Laico was at the controls...

Miles Davis rehearsing backstage at the Chicago Civic Opera House, 1956.Photo: Getty Images

Miles Davis rehearsing backstage at the Chicago Civic Opera House, 1956.Photo: Getty Images

From the laid‑back tempos and intricate arrangements of cool jazz to the experimental, avant‑garde qualities of free jazz; from the fast pace and instrumental virtuosity of bebop to the harsh beat and slower, blues‑based tempos of hard bop; and from modal jazz's avoidance of chord progressions to the electric rock elements, R&B rhythms and funk grooves of jazz fusion, trumpet player Miles Davis tracked the changes and often led the way during a celebrated career that spanned from the mid‑1940s to the early 1990s. Courtesy of some landmark recordings and legendary live performances, Miles Davis transported jazz into uncharted territory, and he did so in collaboration with other gifted musicians whose tastes and talents both complemented and challenged his own.

Still, despite his acclaim as one of the 20th Century's most influential artists, Miles Dewey Davis III led a turbulent life that resulted in a career of peaks and valleys, the latter often caused by his ongoing struggles with drugs and alcohol. It was shortly after kicking a heroin habit that, in 1955 and 1956, he recorded what many fans and critics consider to be his first truly ground‑breaking album. Featuring his signature relaxed, melodic tone — thanks, in part, to the Harmon wah‑wah mute that, by blocking all of the air emanating from the bell of his trumpet, provided it with a warm, high‑pitched buzz — 'Round About Midnight was a masterpiece of the hard bop genre. Despite the lukewarm reception it was accorded at the time of its release, it is now celebrated as one of the finest jazz albums of all time.

'Round Midnight'

Clockwise from top: bassist Paul Chambers, drummer Philly Joe Jones, pianist William 'Red' Garland and Miles Davis.Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Stringer

Clockwise from top: bassist Paul Chambers, drummer Philly Joe Jones, pianist William 'Red' Garland and Miles Davis.Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Stringer

Taking its name from the early‑'40s Thelonious Monk composition 'Round Midnight' — the most‑recorded jazz standard to actually have been written by a jazz musician — the album had its roots in Davis's performance of the song at the 1955 Newport Jazz Festival in Rhode Island. Davis played alongside Monk on piano, Zoot Sims on tenor sax, Gerry Mulligan on baritone sax, Percy Heath on bass and Connie Kay on drums, performing a muted trumpet solo that, in addition to confirming his improved state of health, caught the attention of Columbia Records producer and executive George Avakian, who was in the audience. Avakian was subsequently persuaded by his brother Aram to sign Davis to the label even though he was still under contract to Prestige Records. Thanks to an agreement with Prestige, Davis was able to record for Columbia, and this material could be released as soon as his Prestige contract expired.

Accordingly, after forming what would come to be known as his 'First Great Quintet' — featuring pianist William 'Red' Garland, famous for his block‑chord style of playing the notes of each chord all at once; influentially improvisational bassist Paul Chambers; his all‑time favourite drummer, Philly Joe Jones; and a then‑relatively unknown tenor sax player named John Coltrane — Miles Davis recorded 'Round About Midnight in three sessions, produced by Avakian, at Columbia's 30th Street facilities in New York.

During the first, which took place on October 26th, 1955, the quintet recorded 'Tadd's Delight', composed by pianist Tadd Dameron, plus Stan Getz's arrangement of the Swedish folk song 'Dear Old Stockholm', and the Ray Henderson standard 'Bye Bye Blackbird', all of which would end up on the LP's second side. During the other two sessions, which also took place inside Columbia's Studio C, on June 5th and September 10th, 1956, they recorded 'Round Midnight', based on Dizzy Gillespie's interpretation, Charlie Parker's 'Ah‑Leu‑Cha', and Cole Porter's 'All of You'.

"Aside from all the pluses, working as an engineer for Columbia also had its disadvantages, and one of them was that you just kept recording tunes without knowing whether they were for a particular album or a number of different albums,” says Frank Laico. The engineer of 'Round About Midnight, he's had a career spanning the mid‑'40s to the early '90s, encompassing work with Tony Bennett, Art Blakey, Count Basie, Stan Getz, Leonard Cohen, Johnny Mathis, Frank Sinatra and Barbra Streisand. "It was hard to focus on developing a sound that would fit everywhere,” he adds, "recording songs while remaining unaware how they were going to be released.”

Columbia

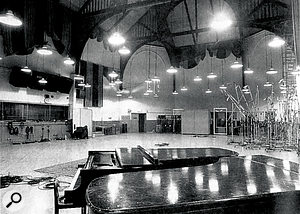

Columbia Studios on East 30th Street, New York. The building, a former Armenian church, has since been demolished.Photo: supplied by Frank Laico/David Simons

Columbia Studios on East 30th Street, New York. The building, a former Armenian church, has since been demolished.Photo: supplied by Frank Laico/David Simons

Now 91 and living in Washingston State, Laico was raised in Upper Manhattan as one of seven children during the Great Depression. Forced to leave high school to help support his family, he was an apprentice to a Bronx butcher, until a customer who was the treasurer for a muzak‑producing organisation named the World Broadcasting Corporation helped land him a job at its Fifth Avenue headquarters. There he operated a mimeograph machine, and one day in 1939, while scouting the 15‑story building during his lunch break for better‑paid employment, Laico followed the sound of music to a recording suite where he saw a group being recorded with eight revolving 16‑inch wax platters. Captivated by both the music and the technological environment, he returned there time and again, and soon his persistence paid off in the form of engineering work, including the mastering of recordings for Columbia Records, which didn't yet have its own cutting facilities.

This brought Frank Laico into contact with Columbia's chief engineer, Vin Liebler, and when Laico was drafted into the US Army following his nation's entry into the second world war, Liebler promised him a job with Columbia once he had returned from the service. In the meantime, Laico's burgeoning recording skills were enhanced by a training course that resulted in a posting to the Pentagon in Washington DC, working on a top‑secret communications operation run by Bell Laboratories.

A baseball injury prevented him from seeing action overseas, and when, after the war, he learned that World Broadcasting were only prepared to re-hire him at his pre‑war salary, Laico contacted Vin Liebler who, true to his word, helped land him a job at Columbia's main studio, located at 799 Seventh Avenue. That was in July 1946, and soon disc cutting and overdubbing had evolved into tape editing and full‑scale recording. Then Laico relocated to the all‑new Studio C, when a former Armenian church at 207 East 30th Street, near Third Avenue, became Columbia's new recording base in the autumn of 1949.

"As soon as I walked in that place, when [A&R Head] Mitch Miller and management were still thinking of buying it, I thought it couldn't get any better than this,” Laico recalls of the 100‑square‑foot live area with its 100‑foot‑high ceilings, hardwood flooring and draped plaster walls. "It sounded good just talking in there. It was a huge space, but it didn't have the hollow sound that you would normally get in a room like that. When I and the other engineers played some music in there, we all agreed that it certainly was a large improvement over what we already had. So Mitch went to management and told them we were excited about it and that we'd like to have that building, but only if we could use it exactly as is, with all of that dust, all of those hanging drapes and everything else to remain just as it was. We didn't want corporate coming in to wash and wax the floors and repaint the walls.

"When I asked Mitch what the reaction had been, he said, 'Everyone on the board looked at me like I was crazy, but I told them that's how it had to be, otherwise forget it.' Well, he got his way, and I didn't realise how important this was until Mitch Miller retired [from Columbia in 1965]. A couple of months later, wouldn't you know it, corporate was in there, painting, washing, waxing, and I was the unfortunate engineer to do the first session after they said, 'OK, it's all fixed, go on in.' The change in the audio was unbelievable, so I called up my boss and I said, 'Mr. Liebler, what Mitch Miller told corporate not to do was so true. Come down here yourself and listen with us. It's impossibly different, and I don't know if we'll ever be able to make it sound like it used to.”

Natural Ambience & Echo

Frank Laico (front) and Columbia producer Bob Thompson at the custom console in Studio 3.Photo: supplied by Frank Laico/David Simons

Frank Laico (front) and Columbia producer Bob Thompson at the custom console in Studio 3.Photo: supplied by Frank Laico/David Simons

Frank Laico's concerns were well founded, and by 1982 Columbia's hallowed Studio C would be no more. However, during its early years, boasting an elevated 8 x 14‑foot control room that housed an Ampex three‑track tape machine and a 12‑input custom‑made Columbia console, The Church was the place where Frank Laico forged a reputation as one of the first engineers to successfully use natural room ambience and echo. That is, after he had discovered a low‑ceilinged, 12 x 15-foot concrete storage room in the basement. Once equipped with a speaker and a Neumann U47, this was transformed into one of the world's best and most acclaimed echo chambers.

"The room itself had its own echo, which was very nice,” Laico says. "However, it would be a different-sounding echo with every session that came in. With the chamber, we could regulate the echo by adjusting the volume of each instrument. Every mic had its own send, so we could set its level, and we could also regulate the return. Still, the sound of that return didn't sustain itself. Then Les Paul told me about how [at his home studio in New Jersey] he smoothed things out nicely by running the sound from the echo chamber through a tape machine. When I tried that, it worked, warming things up and increasing the length of the decay, and afterward everybody in the business — including some engineers from England — showed up, wanting to know how we got that echo chamber sound.”

By playing around with mic positioning and the levels of delay and EQ, Studio C's echo-chamber attributes could be tailored to fit the styles of the various singers who recorded there, providing each of them with their own distinct sound. Such was the case with Tony Bennett, whose 1950 demo of 'Boulevard Of Broken Dreams” was recorded by Frank Laico before he tracked his first hit, 1951's chart‑topping 'Because Of You', after Mitch Miller had signed Bennett to Columbia.

"I really felt like I had found myself,” Laico remarks about his decision to stick with engineering. "I was happy doing it, I enjoyed all of the people I was involved with, and so I thought I might just as well hang in there.”

Which is what he did, learning by trial and error how to mic not only The Church's huge main room, but also Studio B, which housed a 10‑input, custom‑made console and an Ampex three‑track. Laico specialised in capturing their inherent sounds — as well as those produced by the musicians — with a remarkable degree of clarity, and never was this more evident than on his recordings of Miles Davis that commenced with 'Round About Midnight.

Keeping The Musicians Close

Columbia Studio C's live room.

Columbia Studio C's live room.

"I was a very inquisitive engineer, and I used to go out and introduce myself to the musicians, asking them how they felt about the recording methods,” Laico explains. "What I learned was that the most important thing to them was being able to hear each other instead of being so spread out that they couldn't hear, and so I always paid attention to that, even later on when we went to a lot of tracks and microphones. If I had to spread anything, it would never be the rhythm section. I'd spread the woodwinds or brass or strings, depending on the area and how large a space was necessary, and I found that to be the best possible approach when it came to recording. I never asked any musicians if they wanted earphones. I thought that was the worst thing in the world. I'd just keep them close so that they could all hear each other and even talk if they had to. That was the secret for me.

"I always felt that leakage was what made the sound worth listening to. I never wanted to isolate like most engineers unfortunately did, because they wanted things to sound like the kids were recording in their basement or garage. At 30th Street, after trying various places in the room, I settled on having everybody directly in front of the window, not only because that created a better rhythm sound for me but also because I could see everything. I'd use a small baffle about six to eight feet from the bass player, a small baffle in front of the bass drum, and that was all I used on the rhythm section.

"There would be a microphone on the bass drum, another on the hi‑hat, one on the snare and then another mic for the overhead, catching everything, including the cymbals. I'd then put a bag filled with sand inside the bass drum, primarily so that, when the drummer kicked that thing, it wouldn't go all over the room on the wooden floor. It also kept the sound right there, because at 30th Street you could hear the bass drum all over the studio, and so [the bag of sand] made sure it wasn't overbearing.”

While Laico invariably kept the musicians close to one another, he miked each of them from a greater distance than most engineers would do these days. "I never liked the close sound,” he says, "and so even with Miles I would have the mic at least 12 inches away from the horn, and it was the same with the other instruments, like the bass and sax. I just disliked tight sounds — the harshness wasn't normal — and that also applied to vocals. I never had the mic close to the singer: I had it placed over the music stand, so there was air between the voice and the microphone, and it was usually the same with the piano. If the pianist wanted it miked inside, I would do that, but normally I would have the lid open all the way and put the microphones — or microphone, if I was only using one because of the size of the group — about three-quarters of the way up there, a few feet from the keyboard, so that there, too, I would have an open sound rather than a tight sound.

"For me, it sounded so much better, and at times I would have to convince the pianist about this. If he or she wanted a tight sound, I'd say, 'OK, let's start that way,' and then after a while I'd say, 'Now that you've heard it in this room, let me set the mic up a little bit differently so that you can hear that.' Invariably, they liked the mic off the keys — often a [Neumann] 49 — better than the one inside.

"I still had a mono mentality even when we went to stereo, monitoring in mono so that I felt comfortable my stereo was as good as it could be.”

Nervous Anticipation

The contributions of each and every person are now committed to history. Yet, nearly 55 years after his first recording session with Miles Davis, Frank Laico still recalls the anticipation that he felt beforehand, as well as how the two of them bonded.

"I admired his playing and I basically admired Miles, too,” he states. "I know other people found him to be obnoxious and arrogant, but once he and I began working together we became very good friends. He didn't make any comments to me when I set him up with the band. He just looked around and talked to the guys, asking them if they were happy where they were, and when they said they could hear each other we just went from there.

"By the time I began working with Miles, we had the U49, and he had not seen that microphone before. I said, 'I'd like to try this for you. It's got a nice full sound, whereas the 67s are very high‑pitched mics.' He said, 'OK, let's go, we'll listen.' I was extremely nervous, but he was so agreeable, and after we tried the 49 he said, 'I like that very much, it's great,' and that was my start with Miles Davis.

"All of those musicians — Davis, Coltrane, Garland, Chambers, Jones — were great. They knew their instruments and they enjoyed playing together. They used to sit there and just go crazy, playing and playing and playing. After a while, I realised they were having fun warming up, and once we were ready to record they were all set, both mentally and physically. That's why the sessions always proceeded very quickly and very easily. Miles never insisted on sheet music. He would just hand them some kind of music that had his own notations, they would figure out what the hell he meant, and then they'd just go ahead and play. That's how it was with 'Round Midnight' and the other tunes on that record.

"In fact, the first time I really saw Miles using arrangements was when he did the Porgy & Bess album [in 1958] with Gil Evans. That was a challenge, because it was a good‑sized group, and even there I set up the strings and everybody else close to each other so that it was a real live sound. 'Round Midnight', on the other hand, was a great tune, and one that the musicians already knew. George Avakian, Columbia's jazz man, was involved with the arrangements and also as a sounding board, and the musicians loved him. He was a very nice person and very talented, and whatever he suggested seemed to please them. They would always rehearse before we started to record, and we would just let them do what they had to do, talking to each other while making their own corrections and suggestions. Then, once they thought they were ready, Miles would say, 'OK, let's put one down,' and away we'd go. It was very easy.

"While they rehearsed, I sat at the console and listened to what they were doing and how they were doing it, deciding what would work for them with regard to the sound. I always put a little echo on Miles' trumpet, and sometimes maybe a little bit on the sax, the piano and the bass if I thought they needed some more atmosphere. First, however, I would always make a suggestion to the producer and ask if this was all right — I never tried to sneak something in.”

Looking Back

Released on March 18th, 1957, 'Round About Midnight initially elicited mixed reviews, but it has aged very well, with critic Eugene Holley Jr remarking that "The stand-out track is Davis's Harmon‑muted reading of Thelonious Monk's ballad, 'Round Midnight', which is still a Miles standard bearer... If you want to hear the origins of post‑bop modern jazz, this is it.”

Although not scaling the heights of Davis's 1959 modal opus A Kind Of Blue, hailed by many as the greatest jazz album ever made — and engineered expertly by Fred Plaut because Frank Laico, to his subsequent regret, had other studio commitments — 'Round About Midnight is today widely perceived as the high point of the hard bop era. Capturing the only studio performance of Miles Davis's 'First Great Quintet', which had already disbanded by the time the album hit record stores, it is "one of the reasons why people around the world now know Miles Davis and can't get enough of him,” according to Laico, who has engineering credits on no less than 11 of the legendary trumpeter's records.

"Over the years, I worked with hundreds and hundreds of people, I saw a lot of changes in the technology, and I enjoyed every one of them,” he says. "I went to work happy every day and I made no bones about it. My wife often used to say, 'I don't know how you work all those hours and keep smiling,' and I'd tell her, 'It's because I'm enjoying myself.' I loved going to the studio.”

Artist: Miles Davis

Track: ''Round Midnight'

Label: Columbia

Released: 1956

Producer: George Avakian

Engineer: Frank Laico

Studio: Columbia

Hands On & Hands Off

"I was usually too busy to remix if this was required later on,” explains Frank Laico, "and so I'd set up all the microphones to where I thought the instruments should be to get a natural live sound. You see, after the engineers finished their work, the tapes then went to the editing department, and those fellows either followed how you set it up or they would try to change it, taking the three‑track and mixing it to their ideas of how the band should sound. In those days, we always wanted a complete take, and if we didn't get one we'd make inserts and these would be spliced together by the editors.

"Early in my career, when I wasn't so busy in the studio, I'd go into the editing room and work on the finished product. However, once we got into multitrack and I began doing three three‑hour sessions a day — plus all of the setting up and tearing down — it was impossible for me to follow through and also do the remixing. I would just go in and check every so often to make sure the editors weren't going too far astray. As far as I was concerned, that was their job, making splices with inserts and so forth, and once that was satisfactory they would then start running the tape for a complete master.”