REM's first single wasn't just an embryonic form of the style and sound that would later make them so successful, it was also a gem of the American new wave. But it took a long time coming...

Mitch Easter joins REM on‑stage at the 9:30 Club, 1982. From left to right: Michael Stipe, Mike Mills, Peter Buck, Bill Berry and Mitch Easter.

Mitch Easter joins REM on‑stage at the 9:30 Club, 1982. From left to right: Michael Stipe, Mike Mills, Peter Buck, Bill Berry and Mitch Easter.

"Keep me out of country in the word / Deal the porch is leading us absurd...”

Complete babbling? That's how Michael Stipe once described his lyrics to REM's first chart single, 'Radio Free Europe', and many listeners would agree. Stipe, after all, has never been averse to employing a memorable title or an oblique, oddball phrase that has little connection to a song's meaning. Yet it was this idiosyncratic approach, so ably demonstrated on 'Radio Free Europe', that would eventually see the band become favourites of the burgeoning '80s college-rock scene before finally crossing over into the mainstream with such phenomenal success. It's all there in that first single: from the obscure, sometimes unintelligible vocals to the minor‑key guitar jangle, 'Radio Free Europe' is a blueprint for the REM sound.

It wasn't an easy birth though: the single was demoed, recorded, remixed, recorded again and released in two very different versions, the first in 1981 and the second two years later. Fans of the Athens, Georgia outfit have spent a commensurate amount of time during the past three decades debating which version is better: the original neo‑punk recording that, as released on the independent Hib‑Tone label, is favoured by the band members themselves, or the slower, slightly more textured IRS release that made the lower reaches of the Billboard Hot 100.

"When I hear the second version now it sounds a little too sedate,” says Mitch Easter, who earned production and engineering credits for both recordings of 'Radio Free Europe', as well as for REM's first two albums, Murmur and Reckoning. "It's more hi‑fi, for sure, but it's also heavier and the energy is a little different. I think it's saved by Michael's vocal and the cool bass line on the transition to the chorus, but I kind of prefer the faster speed.”

In The Beginning...

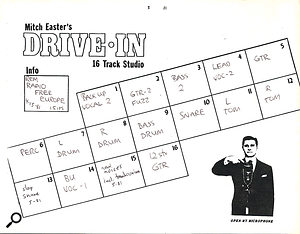

The track sheet for the original version of 'Radio Free Europe'.

The track sheet for the original version of 'Radio Free Europe'.

A native of Winston‑Salem, North Carolina, who had played in school and college bands since the age of 12, Mitch Easter graduated from college in 1978, and had initially relocated to New York City with the intention of launching a studio there while still playing in bands. However, within a couple of years, unable to afford the Big Apple's high overheads, he launched the Drive‑In back in North Carolina, and it was around this time that Michael Stipe and guitarist Peter Buck teamed up with fellow University of Georgia students Mike Mills (bass) and Bill Berry (drums) to form REM.

Following several months of rehearsals, the group quickly built a strong local following on the club circuit, and it was after adding 'Radio Free Europe' to the set list and opening for the Police at the Fox Theatre in Atlanta that, on April 14th, 1981, the Athens quartet showed up at the Drive‑In to record a demo. This was thanks to a recommendation by another Winston‑Salem native, Peter Holsapple, who, with Chris Stamey, had founded a jangle‑pop outfit called the dB's.

"I had heard of REM and I'd seen a poster of them in a club,” says Easter, who had formed his own jangle‑pop trio, Let's Active, "but I still didn't really know what the guys did until they started recording the next day, and at that point I was kind of surprised at the music they performed. They had a funny sensibility, because back then many bands were on one side of the punk fence or the other, whereas these guys were in their own sort of category.”

Three songs were recorded in one day and then mixed the next: 'Radio Free Europe', 'Sitting Still' and the instrumental 'White Tornado', all of which had already been tracked by REM the previous February at the Bombay Studios facility of producer/engineer Joe Perry (not to be confused with he of Aerosmith) in Smyrna, close to Atlanta, along with five other tracks. The Bombay recordings have never seen the light of day. However, according to Mitch Easter, who has a copy of the tape, 'Radio Free Europe' sounded much the same as during the Drive‑In session, even though the lyrics weren't yet complete.

"They had been working on this stuff and playing it live, and the session was one of those super‑cut‑and‑dried things,” he recalls. "They pretty much just bashed it out, we did a few overdubs, and Michael was really into doing these kind of subliminal second vocals, making little whispering noises. Then, once I had spliced a weird noise onto the beginning of 'Radio Free Europe' to create a moody feel — captured with a Lexicon Prime Time M93 digital delay, which was the only digital device I had back then — and put that funny triangle sound in the middle, we were finished. I don't think there was any real plan for the tape at that time. They just made cassettes of it to give to their friends and take to the clubs.”

Secret Singing

At the time of the first recording of 'Radio Free Europe' the lyrics were still incomplete. Michael Stipe used the back of the track sheet to make some notes.

At the time of the first recording of 'Radio Free Europe' the lyrics were still incomplete. Michael Stipe used the back of the track sheet to make some notes.

From the perspective of the control room being in the lower right corner of the overall studio, the iso booth being in the lower left corner and the live area running from right to left along the top, Bill Berry's drum kit was positioned against the right wall of that live area and multi‑miked with a setup that Mitch Easter can't now quite recall.

"There were probably AKG 414s overhead and a bunch of funny choices on the other drums, like AKG [D]1000s, which you never see anymore,” he says. "I do remember that we recorded the guitar with an EV 635, a cheap omnidirectional mic that I love and which is really great on guitars. I still use it sometimes.”

While the guitar and bass amps were both in the iso booth, Michael Stipe recorded his vocals in the same room as the drums, tucked away in the far corner, facing the wall.

"He didn't want anybody to see him sing,” says Easter. "However, we knew he was there, we could hear him. That was for his scratch vocals, and then we overdubbed him. In fact, I've still got some tapes with the scratch vocals, and you can tell he's in the room with the drums because it sounds like the drums are about four feet away from him... For the real vocals I would have definitely used one of the 414s — those were my fancy microphones — whereas for the scratch vocals I could have used anything: probably some dynamic mic that was lying around.

"Michael's one of those guys who always sounds like himself. He sounds good on anything really. And while I quickly realised that his style of singing, which can be hard to understand, was a big deal to people, I really don't think it ever crossed our minds at the time. To me, there was a grand tradition of singers who you have no idea what they're saying, and so I thought Michael just sounded cool. You could get enough words here and there to tell he was singing something. The funny thing is, he wrote the lyrics on the back of the ['Radio Free Europe'] track sheet from that session, which I've still got, and they were the same throughout; it was just his delivery.

"He really was one of those glorious amateurs — he didn't have a long heritage of being in bands, and he was like a classic art student who thought it was his job to invent something. You know, some people come to the studio and say, 'I want to get this Jimmy Page guitar tone,' but Michael would think that is embarrassing. He wanted his own sound, and so it was possibly just part of his general mindset that not singing clearly was what he should do.”

Remix & First Release

Don Dixon (left) and Mitch Easter at Reflection Studios, early 1983.

Don Dixon (left) and Mitch Easter at Reflection Studios, early 1983.

Following the initial session, the next time Mitch Easter saw REM was on May 25th, 1981, when they returned to the Drive‑In alongside a 27‑year‑old University of Georgia law student and musician named Johnny Hibbert. Having recently formed his own Atlanta‑based Hib‑Tone label, Hibbert had seen the band perform live and, in return for them handing him the publishing rights to 'Radio Free Europe' and 'Sitting Still', he was overseeing the remix of both tracks in order to release them as the 'A' and 'B' sides of the group's first single.

"To my mind, he didn't know what he was doing and, with just two compressors, my spring reverb, the Lexicon delay and the limited EQ on the Quantum [desk], I didn't have any way to enhance what we had already done,” remarks Easter, whose own mix wouldn't be issued until the release of REM's first compilation album, Eponymous, in 1988. Instead, despite the protests of band members that the remix sounded even murkier than the original — especially Peter Buck, who broke a copy of the finished single and nailed it to his wall — Hibbert ensured that, since he was financing its manufacturing and distribution, this was the version released in July 1981.

The limited initial pressing of 1000 copies sold out rapidly and garnered critical attention, with Robert Palmer naming 'Radio Free Europe' one of the Top 10 Singles of the Year in the New York Times and Tom Carson of the Village Voice citing it as "plain and simple, one of the few great American punk singles”. Although that assessment now seems wide of the mark, the recording was, undoubtedly, a remarkable debut as well as a fine example of early‑'80s power pop, with its ringing guitars, melodic bass, compelling beat, catchy chorus and, of course, occasionally incomprehensible vocal. And it also brought REM to the attention of IRS, the record label owned by Miles Copeland which, courtesy of a roster that included the Buzzcocks, the Cramps, the Fleshtones and the Go‑Gos, appeared to be well suited to the Georgia band's brand of music.

Reflection Studios

By mid‑1982, a cash‑strapped Johnny Hibbert was out of the picture, having sold REM the publishing rights to 'Radio Free Europe' and 'Sitting Still' for just $2000. This would prove to be fortuitous in light of subsequent events. Yet, in a misguided attempt to pitch the band into the mainstream, IRS initially attempted to kick Mitch Easter to the kerb too, by having an unknown producer named Stephen Hague helm REM's first album. Hague would subsequently find success working with New Order, the Pet Shop Boys and Erasure, but REM didn't like his rigidly disciplined approach or his overdubbing of then‑fashionable synthesizers, and so they reunited with Mitch Easter to record another new number, 'Pilgrimage'.

Easter wasn't taking any chances. Aware that he was auditioning to produce the album, he agreed to forgo his 16‑track Drive‑In facility for the 24‑track Reflection Studios in nearby Charlotte, and he also asked Don Dixon, an old high-school friend who had become an engineer, to partner him behind its 56‑channel MCI 600 Series console. As Easter himself points out, "Don had already worked at Reflection and I didn't want to waste everybody's time trying to figure out how the equipment worked.”

Easter's approach succeeded. REM liked the recording and both he and Dixon were hired to produce and engineer the album at Reflection.

"It was a really, really good studio,” asserts Easter who, in addition to performing under his own name, today produces bands at his Neve VR/Pro Tools‑equipped facility, The Fidelitorium, close to where the Drive‑In used to be. "A lot of times, there's an assumption that Reflection was this weird backwoods place, I guess because it was in the South, but it was really nice, with a big '70s‑style room — which actually wasn't dead‑sounding — and plenty of the latest gear.”

This included an MCI JH24 tape machine, in addition to an Ampex ATR100 two‑track machine and a good assortment of new and vintage microphones.

"One of the holdovers that the main room had from the '70s was a tiny little drum booth in the corner, and Bill absolutely demanded to be recorded in there,” says Easter. "Dixon and I thought that was hilarious, because drum booths were so out of fashion back then. But still, we did use the booth and it was kind of cool. I'd never used one before. The two of us, you see, were very down‑to‑earth about stuff — we would have laughed at the idea of recording 48‑track, for example, saying, 'Oh, come on, we can do this on eight‑track!' We had that sort of macho attitude toward everything, and so to us 24‑track was incredibly posh and more than we needed.”

The Power Of Veto

"Our whole working relationship was incredibly informal and I'm proud to say that I really don't remember who did what. I mean, being more familiar with that place, Dixon could reach for something immediately because he knew where it was. But if some people think he was the engineer and I was the producer, that wasn't the case at all. For one thing, Dixon was drastically more experienced than I was, so he just jumped right in there. My favourite kinds of sessions are ones where everybody's talking all the time, the good ideas are obvious, that's what we do and we don't care who suggested them. So, there was lots of involvement from the band, lots of involvement from us, and since Dixon is a real easy guy to be around it was a very comfortable, unstructured kind of arrangement.

"Then again, the whole we‑need‑a‑hit attitude of the record company really freaked the band out, and the sessions they had done [with Stephen Hague] had really made them think that the studio was the place where you get turned into a cheese‑ball. They were super‑resistant to things that a year before they would have thought were cool, and that was a problem. We couldn't just stick microphones in front of them, do a live set in the studio and be finished — that wouldn't quite sound like what was needed, especially with their songs. They weren't the Buzzcocks. Their stuff needed a little more work on it, and so we had to kind of fight a little to make a proper record in our opinion. This involved a slow negotiation with them to figure out what was OK and what was not, and in that sense, while they weren't necessarily coming up with the ideas, they had this veto power.

"As the veto power became more clear to us, we were then able to speak a little more efficiently about ideas. Basically, it came down to them liking any kind of real instrument, like a piano, and hating any electronic instruments. OK, no problem. We were able to use a lot of stuff that the studio had. Studios back then — especially, it seems, studios in the South — were always good about having nice pianos and organs, and Reflection also had a vibraphone. As I was really enamoured with the band ABC at that time, I was able to talk them into using the vibes on some stuff. I loved the vibes on the ABC record, and so we were able to sneak in some sounds like that which [REM] also liked. They were really smart about that in a way, because if they had made a record with a bunch of synths it would now be really dated. As it is, you can't really tell when Murmur was done, and that's kinda cool.”

Take Two

This time around, while Bill Berry's drum kit was conventionally miked in the booth — "I'm sure we had an [ElectroVoice] RE20 on the bass drum, because that's what you did in the United States at that time” — Mike Mills played his Rickenbacker bass through the studio's Ampeg B15 amp which was recorded with a distant mic in a small corridor. "I had probably just read that Geoff Emerick miked Paul McCartney from about eight feet away,” Easter says. "We would try stuff like that, and sure enough it worked.”

Standing on the left side of the studio, Peter Buck used Easter's own Ampeg, wide open without gobos and miked with an EV 635 or, for some overdubs, a compressed Neumann U47 FET. Meanwhile, a second FET 47 was used for Michael Stipe's vocals, which he recorded standing on the landing of a staircase positioned just below the control room and above a recreational basement area. "He still had this thing of loving to be invisible,” remarks Easter, "and so he'd go there, turn off all the lights and sing.”

While the vocals remain typically indistinct, the jangling guitars sound brighter and the punchier bass carries much of the melody, the introspective, evocative mood and folk‑rock feel of Murmur are perfectly encapsulated by the slower, cleaner, IRS‑commissioned remake of 'Radio Free Europe', with its strange opening created by Mitch Easter triggering a purposely stored, errant system hum to open and close a noise gate in sync with the bass.

"We kept accumulating noises in the course of that record,” Easter explains. "You know, those guys were art‑farts in a way and they loved that sort of musique concrète stuff that can happen from some random noise. I can't now remember what that sputtery noise was, but we made a loop from it and keyed it to the bass guitar pattern of the transitional part that leads into the chorus. We were always doing stuff like that. It may sound like a drum machine, but a drum machine would have gotten Dixon and me fired immediately! The thing with REM was that they liked stuff if they could see it from an art angle, but the minute they thought something was hokey or done for commercial appeal they hated it.”

The Better Version?

Recorded and mixed during January and February of 1983 and released that April, Murmur was critically acclaimed and voted Rolling Stone's Best Album Of The Year, beating Michael Jackson's Thriller, the Police's Synchronicity and U2's War. Nevertheless, while the plaudits were appreciated, the liner notes to the 1988 Eponymous compilation would reveal that both Mike Mills and manager Jefferson Holt thought 'Radio Free Europe' in its Hib‑Tone form "crushes the other one like a grape”.

Mitch Easter, who last summer performed with REM and Don Dixon at a concert in Raleigh, North Carolina, conjures a compromise.

"I wish we could impose the sound quality of the second version on the performance of the first one,” he says. "Now that would be something.”

Artist: REM

Track: 'Radio Free Europe'

Labels: Hib‑Tone, IRS

Released: 1981 & 1983

Producers: REM, Mitch Easter, Don Dixon

Engineers: Mitch Easter, Don Dixon

Studios: Drive‑In, Reflection

At The Drive‑In

Mitch Easter was barely a year into the business when he recorded REM's debut single at the appropriately‑named Drive‑In home studio that he had set up in a converted two‑car garage with a basic assortment of second‑hand gear.

"My parents had bought this house while I was in college, and the 24 x 24 foot two‑car garage had been converted into a bedroom and a one‑car garage,” he now recalls. "The bedroom had then been divided into two rooms, and so this gave me three rooms for the studio: the long room for the car became the live area, with rugs and amps covering the concrete floor; one of the smaller rooms became the control room, with a window to the live area that I created by sawing a hole in the wall; and the other little room became an isolation booth. It was incredibly primitive, but I was young and dumb enough to not think this was tragic.

"After buying all of this used equipment, the bare minimum you could make records with, I just started up shop. I didn't have any training or professional experience, but having already made tons of four‑track recordings at home on a TEAC 2340 with my friend Chris Stamey — using only an Echoplex and a TEAC device that would switch the four outputs to left, right or centre — I figured, 'Well what's the difference?' It really wasn't all that different. The four‑track had been fantastic in terms of learning how things worked, and I was right in figuring the pro stuff would be the same, except I had to start all over again because it was much more clean‑sounding. This great fur that the old four‑track had put on everything made it all hang together, and so now I had to re‑learn what I was doing.

"I had two 3M tape machines — a classic M56 two‑inch 16‑track and the equivalent M64 two‑track machine — along with a pair of ADS 810 monitors and a Quantum Audio board manufactured in California by one of the very few companies that were still making humble pro‑level consoles. It was a 12‑channel board with an eight‑channel sidecar, bolted together at the factory to custom order. With 20 inputs, 16 tracks of monitoring, three‑band EQ on every channel, a couple of aux sends and a couple of echo sends I thought I was really living. It was an unbelievable leap from anything I had ever used before. Everything worked pretty well and I also bought a couple thousand dollars of good microphones, the showpieces being two AKG 414s.

"Everything was learned as I went along. With the TEAC, Chris and I had originally put two microphones on the drums, which was a good introduction to moving the mics around until everything sounds good, and then later, when we had four or five microphones, we started messing around with individually recording more parts of the kit, and from that I learned a lot about just tuning the drums. The fact that we had no EQ and no nothing made us get the sounds totally with drum tone and mic placement.”

Hi‑hat Hassles...

Interesting effects abound on the remake of 'Radio Free Europe', as the otherwise plain song was deemed to require a little more mystery. Accordingly, in addition to some percussive sounds, the clanging noise in the middle of the song is a triangle treated with analogue delay, the timing having been adjusted to make it go out of tune. Still, the biggest challenge? Well, that had to be Bill Berry's all‑pervasive hi‑hat...

"For some reason, Bill played his hi‑hat really loud in those days, and when we got into the tracks we realised it was everywhere. Hi‑hats can be like that — we even had hi‑hat in the bass drum, way beyond what we could handle. So, we started doing some really funny things with Bill's drums, like decoding the mic input through a Dolby A unit as a sort of high‑frequency dynamic expander. This got the hi‑hat out of the bass drum, and although it was heavy‑handed, it worked.

"We also did some other stuff on that song. The snare was kind of boring, with so much hi‑hat noise in there you couldn't hear its brightness. So, we actually overdubbed the snare, which I played and Dixon punched in, and we did that when the guys weren't there because we knew they'd hate the idea. We mixed it in to give us a little bit of clarity, and it was recorded in a cool way. We had a microphone about 10 feet above it and a whole load of compression to suck in some room noise, and it made this splat sound that was kind of cool. A lot of the snare sound comes from that overdub.